COMMENTS ON THE ART MARKET

Upcoming Gallery Exhibition

Seaside

Opening May 13th

A Drop in the Ocean: Contemporary Seascapes at Rehs

Humans have been fixated on the ocean for centuries as one of the world’s ultimate mysteries. It’s a vast space that occupies most of our planet, yet even to this day, it remains one of the last great symbols of the unknown. This is one of the main reasons artists have been drawn to the ocean and its relationship with humans.

The seascapes showcased at Rehs Contemporary can be categorized into two distinct themes: the ocean as the primary subject, and the ocean in relation to humankind. Seascapes with the ocean as the primary subject are vivid depictions of the sea’s volatile nature. Whether it’s Gail Descoeurs’s The Ocean Breeze or Brett Scheifflee’s Winter Waves, the ocean manifests in a multitude of forms. A seascape can capture the sea’s beauty and power, but also its turbulence and unpredictability. From tranquil to tempestuous, the ebb and flow of the tides, the ocean, frozen in a single moment through a seascape, stands as one of nature’s most compelling symbols of change. In the pictorial arts, the sea has been an incredibly popular subject, especially among nineteenth-century Romantic artists like Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner. These painters created seascapes where the ocean was the main focus, featuring human figures and other objects to emphasize its enormity. This comes from Romantic artists’ fixation on nature’s awesome and overwhelming essence, or what Edmund Burke called “the sublime”.

Meanwhile, some paintings illuminate humans’ profound connection with the sea. These artworks depict the ocean as a source of recreation, as seen in the beach scenes by Mark Daly and Sally Swatland. However, they also portray the sea as a conduit of transportation, as evidenced in John Stobart’s paintings showing renowned ships at sea. An oceangoing vessel symbolizes humanity’s deep-seated love and fascination with the ocean while also underscoring our relentless pursuit to harness the wind and the waves for our own endeavors.

Introducing

Carrie Goller

Introducing Carrie Goller, a talented artist hailing from Bainbridge Island, Washington. Carrie's captivating work seamlessly blends classical techniques with daring experimentation, drawing inspiration from the organic forms and vibrant colors found in nature. Her diverse portfolio spans across various genres and mediums, including oil, cold wax, encaustic, and egg tempera, often combined into mesmerizing mixed media pieces. A graduate of Northwest College of Art & Design, Carrie finds her muse in the scenic surroundings of her Hood Canal seaside studio, where she continues to push the boundaries between tradition and innovation. We are thrilled to welcome Carrie Goller to our gallery, where her unique vision promises to captivate and inspire.

____________________

Stocks & Crypto

Welp, it finally happened… we had our first down month of the year. It’s been one heck of a ride so far in 2024, and even after this correction, we are still up for the year. Nevertheless, the volatility is concerning. Going into April, all three major indexes were holding solid gains for 2024… the Dow was up over 5.5%. the NASDAQ was up over 9%, and the S&P was sitting pretty with a 10% gain! Those figures [for the year] now sit at just .34%, 3.9%, and 5.2%, respectively. Interestingly, a report in the final days of the month showed US workers achieved bigger gains than expected with respect to wages and benefits in the first months of the year; while that is good news for workers and the overall strength of the job market, it has manifested info fears that there will be persistent upward pressure on inflation… in that same breath, the Fed just announced (on May 1st) that it would maintain stubbornly high-interest rates, citing a lack of progress on inflation. As I’ve been saying, there really isn’t much to substantiate the gains we’ve seen so far this year, and that continues to be the case… at least, in my opinion… but again, what do I know?

Turning to currencies and commodities… relative to the US Dollar, both the Pound and Euro experienced a moderate slide – the Pound weakened a bit more than 1%, while the Euro was down about 1.2%. Crude was up early in the month but gave back most of the gains… by close on the final day, it was sitting up just .7%; it’s also worth noting on the first day of May, Crude plunged further to a nearly 3% loss from the start of April. Then there’s gold… I honestly cannot recall the last time I saw movement like this in gold futures – by the third week of the month, gold had popped more than 10%, and achieved an all-time high! It gave some back in the final week but is still hovering in the $2,300 region. Again, this points to investors' sentiment on inflation and hedging that risk.

In the crypto arena, we saw a pullback from record levels. Bitcoin continued testing its all-time high, which was set back in March. After fluttering just shy of $73K, Bitcoin has fallen back below $60K; down more than 18% this month! Ethereum fared slightly better, with a loss of 15%, while Litecoin plummeted nearly 24%. All around, a rough month on the blockchain.

April was certainly a month to forget… although we are still technically in plus territory, the volatility underscores the current uncertainty in the economy. More directly, it highlights why it is prudent to use a cautious and conservative investment strategy at a time when it has become apparent that the gains we are seeing are not supported by the fundamentals.

____________________

Really!?

The Brooklyn Museum Sells Out

Walnut Fitted Cellaret

The Brooklyn Museum recently succeeded in deaccessioning several rooms of antique furniture and decorative art, a process often regarded with skepticism within the museum community. Typically, there are strict guidelines governing deaccessioning, including the requirement that any funds generated must be earmarked to acquire new works. Moreover, curators must provide:

A comprehensive list of reasons justifying the removal of the items.

Citing factors such as poor condition.

Inability to adequately care for the pieces.

Misalignment with the museum’s mission or goals.

Even when executed according to these guidelines, deaccessioning can still provoke controversy, as seen in the recent sale of a Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington by the Metropolitan Museum.

Founded in 1895 as the Brooklyn Institute of Arts & Sciences, the Brooklyn Museum originally served as a cultural institution for the independent city of Brooklyn before its incorporation into New York City in 1898. Over the years, the museum has faced challenges akin to a spring-cleaning dilemma, necessitating difficult decisions to optimize space and financial resources. In this vein, the recent decision to part ways with four period rooms reflects a bittersweet yet necessary process.

The museum entrusted the contents of these rooms to Brunk Auctions of Asheville, North Carolina, leading to a remarkable auction event featuring hundreds of objects spanning various periods and regions. From delicate ceramics to robust furniture, the auction presented a whirlwind journey through history, with esteemed names like Matthew Bolton and Le Corbusier adding prestige to the proceedings.

The auction surpassed expectations, raising over $678,000 — more than two-and-a-half times the initial estimate of $254,000. Notably, an eighteenth-century Virginia Chippendale walnut cabinet fetched $95,000 ($116,850 with premium), well above its estimated value of $40,000. Other highlights included furnishings from the Abraham Harrison House and woodwork elements from the dining room at Cane Acres Plantation, which exceeded their estimated values.

Despite the financial success, the museum’s decision sparked debate among critics, who questioned the implications of selling historical artifacts and its potential impact on the institution’s identity. However, the museum’s director, Anne Pasternak, defended the move as a strategic effort to create space for new acquisitions while maintaining the museum’s core ethos—a delicate balance between honoring tradition and embracing progress.

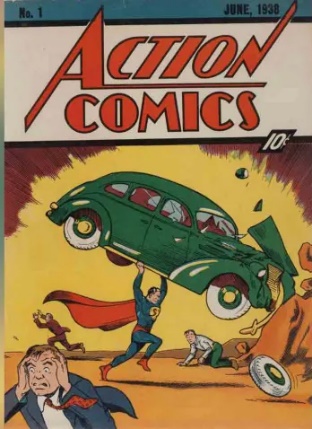

Supreman Soars At Auction

In the realm of comic book collecting, the rivalry among superheroes extends beyond the pages of their adventures to the auction houses where their iconic issues command staggering prices. The dynamic between Superman and Spider-Man, two titans of the genre, has witnessed shifts in the hierarchy of comic book values over the years.

Action Comics #1, a monumental milestone marking Superman’s historic debut, has long held a position of unparalleled significance in the world of comic book collecting. Its role as the cornerstone of the superhero genre and the embodiment of hope and justice has elevated it to the status of a global treasure.

For years, examples of Action Comics #1 set auction records; however, in 2021, the emergence of Amazing Fantasy #15, Spider-Man’s inaugural appearance, marked a significant turning point. Graded at an impressive CGC 9.6, it fetched a staggering $3M ($3.6M w/p) at auction, toppling Superman from his perch and crowning the web-slinger as the new king of comics.

Yet, in a testament to his resilience and enduring popularity, Superman staged a triumphant comeback in 2022. A Superman #1, graded CGC 8.0, soared to new heights, commanding a remarkable $5.3 M in a private sale. Once again, the Man of Steel asserted his dominance, reaffirming his enduring legacy and cultural significance.

Recently, a pristine copy of Action Comics #1 (1938) from the esteemed Kansas City Pedigree collection—a treasure trove of nearly 250 pristine #1 issues spanning from 1937 through the ’40s—graded Very Fine+ 8.5 by CGC (Certified Guaranty Company, also known as CGC is a comic book grading service), fetched an astonishing $5 million ($6M w/p). There are just 78 copies of Action Comics No. 1 in CGC’s population report, with the grading service estimating a scant 100 survivors of the comic book. It is believed that DC Comics printed 200,000 copies.

This historic sale not only reaffirms Superman’s unrivaled status but also underscores the enduring power of his symbol—a beacon of hope that transcends generations and continues to inspire millions around the world.

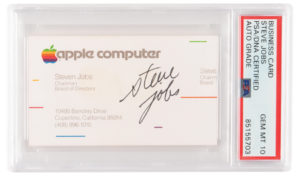

The Allure Of Steve Jobs And The Apple Computer

The recent auction hosted by Boston-based RR Auction, titled Steve Jobs and the Apple Computer Revolution, showcased the enduring allure and value associated with items linked to Apple’s iconic co-founder, Steve Jobs, and the groundbreaking company he helped build. Despite recent antitrust scrutiny, Apple’s reputation remains intact among its dedicated followers.

Some of the auction’s standout offerings were six lots featuring Jobs’s signature, with two commanding six-figure sums. Notably, a 1983 business card soared past its estimated value, selling for an impressive $145K (est. 10k+, $181K w/p). Not only does the card have Jobs’s signature, but the top is adorned with the vintage, rainbow-colored logo Apple used between 1977 and 1998. A little later on in the sale, a Wells Fargo check from 1976, likely funding the early Apple-1 prototypes, fetched a remarkable $141.5K (est. $50K+, $177K w/p). These sales underscore the profound impact that Steve Jobs and Apple have had on modern society.

The auction also spotlighted significant artifacts that trace Apple’s evolution into America’s most valuable company. Particularly noteworthy was a fully operational Apple-1 from 1976. This was the very first product made by Apple Computers, but it may not seem recognizable as a computer today. It mostly consists of a central processing unit, a microprocessor, and memory chips on a circuit board. Buyers were expected to have their own monitors and keyboards so they could hook them onto the Apple-1. The Apple-1, however, was not much of a success. After selling the first twenty-five units, Jobs spent all the company’s money to make one hundred more despite there not being comparable demand. Its CPU was not powerful enough to compete with other personal computers available on the market at the time. Though not as successful or iconic for the company as the Apple II or the Macintosh, the fact that the Apple-1 was the first anything from a now-legendary company has made it a part of history. The particular computer sold at RR Auctions is signed by Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak. This board nearly reached its estimated value, selling for $260K (est. $300K+, $324K w/p).

Sealed first-generation iPhones and other early Apple products remain highly coveted, with a 4G model fetching $118K (est. $50K+, $147K w/p), further illustrating the enduring demand for Apple-related memorabilia.

Overall, the auction underscores the surging interest in Apple-related collectibles, reflecting an ongoing fascination with the company’s storied history and Steve Jobs’s visionary leadership. Memorabilia from Apple’s formative years and items associated with Jobs himself have emerged as a distinct and lucrative category in the auction market, preserving the legacy of one of the most influential companies in modern technology.

____________________

The Dark Side

Still Missing: The Giza Van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

The most recent incident in our ongoing Still Missing series is the theft of a Van Gogh painting in 2010. Poppy Flowers dates to 1886, during Vincent van Gogh’s time in Paris, and measures 26 by 21 inches. Some scholars say that it was the first Van Gogh painting bought by a collector from outside Europe or North America, with the Egyptian collector Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil Pasha having bought it sometime in the 1920s.

Khalil’s collection forms the basis of the Khalil Museum in Giza. It contains one of the greatest collections of European paintings outside Europe and North America. On top of being an art collector, Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil Pasha was a prominent Egyptian politician, serving in several cabinet positions before becoming the equivalent of prime minister on two occasions. Before attaining these positions, he studied law at the Sorbonne in Paris, where he started collecting French paintings. By his death in 1941, Khalil and his wife Emilienne were some of Egypt’s top art collectors. Emilienne bequeathed their art nouveau-style mansion in Giza to the Egyptian state upon her death in 1962, opening the Khalil Museum to house their art collection soon after. The museum consists mostly of Barbizon landscapes by Daubigny, Harpignies, and Corot, Impressionist paintings by Monet, Morisot, and Pissarro, and a few assorted sculptures by Rodin. There are many paintings by Egyptian painters as well. But the most famous Khalil collection work was probably Vincent van Gogh’s Poppy Flowers.

When Poppy Flowers was displayed at the Khalil Museum, it was hung on the wall in its own room, almost like some holy relic meant for veneration. The Khalil Museum has never been the most popular attraction in the Cairo area. Therefore, the staff’s attention to security likely grew relaxed. On August 22, 2010, only a couple hours after opening, museum staff found that the Van Gogh had been cut from its frame and replaced with a replica. Egypt’s culture minister, Farouk Hosni, implemented measures to prevent the painting from being taken out of the country.

Within a few hours of the theft’s discovery, an Egyptian news agency announced that a pair of Italians were caught with the painting at Cairo International Airport. The Italian tourists had been to the Khalil Museum that day, with museum officials pointing them out to the authorities after remembering some suspicious behavior. However, the two Italians did not have the painting with them, leading to Hosni quickly retracting his announcement that the Van Gogh had been recovered. Embarrassed, Hosni deflected by blaming the Khalil Museum’s director and several staff members. He accused them of “negligence and failing to carry out their employment duties”. Hosni also called for a full investigation into the incident. In the end, prosecutors uncovered the full extent of the museum’s security risks. Only seven of the forty-three security cameras were functioning, while none of the fifty-four security alarms worked.

A month after the initial theft, the Egyptian interior ministry announced that it was likely that a museum employee stole the painting or was somehow involved in the theft. Despite this insight, there were still no new leads.

The theft’s fallout left the museum’s doors closed for nearly ten years while they renovated the building and upgraded its security. The Khalil Museum only reopened in April 2021. Its reopening is often seen as part of the Egyptian government’s efforts to bolster the country’s cultural sector. These cultural campaigns also included the opening of the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in 2017 and the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza just last year.

Before and after the theft, the Khalil Museum was never Egypt’s most popular cultural institution. Foreign tourists tend to be drawn more toward Egypt’s archaeological sites and the museums dedicated to its ancient history. People would rather come to Egypt to see the pyramids than Pissarro. Therefore, going to a small museum full of French Impressionist paintings may seem silly since people visiting from Western Europe or North America could see those in their own country’s museums. After fourteen years, the chances of recovering the Van Gogh grow smaller and smaller.

Ukrainian Museum Calls Out Russian Looting

(Photo Courtesy Kristina Fedorovych)

A Ukrainian museum has shown that Russian forces looted thousands of items, including nearly one hundred paintings, successfully transferring them to other museums in Russian-controlled areas.

In a Facebook post on March 29th, the Kherson Museum announced that it had identified ninety-nine paintings previously in its collection that were looted by the Russian military during their eight-month occupation of the city. The museum confirmed this thanks to a video made at the Tavrida Central Museum in Simferopol in Russian-controlled Crimea that aired on Russian television in September 2023. In its statement, the museum explained, “Looters document their crimes themselves, and this allows us to determine the whereabouts of at least part of the stolen goods.”

These stolen works include A Gloomy Day, an oil on board painting by Efrem Zverkov, one of the most prominent twentieth-century Soviet landscape painters who was also associated with the “severe style” of Soviet realist painting in the 1950s and 1960s. There was also Fishermen on the Seashore by Ivan Shulga, a 1932 oil painting done on paper laid on board. Shulga was a native of the Kherson area but spent much of his career up north in Kharkiv. Fishermen on the Seashore is a classic example of Soviet socialist realism popular throughout the Stalinist era, which promoted the benefits of life under socialism and, more importantly, valorized working people. The stolen works identified in the video also included those by modern and contemporary Soviet and Ukrainian artists like Venera Takaieva, Ksenia Stetsenko, Ivan Starenkov, Anatoly Platonov, and Antonin Fomyntsev. Furthermore, the Kherson Museum has identified works by foreign artists, like the Czech cityscape painter Jaro Procházka, as having been stolen by the Russians. Besides Simferopol, the Kherson Museum has also identified paintings at a museum in Henichesk, a city in the Kherson region under Russian control. A different video shows a painting by Konstantin Korovin entitled Phaeton in Sevastopol, previously kept by the Kherson Museum, on display at an event in Henichesk celebrating the tenth anniversary of Russia’s unrecognized annexation of Crimea.

According to the museum’s post, “In fact, the 100 identified works are a drop in the ocean, less than 1% of what was stolen, because under the guise of the so-called ‘evacuation’, the occupiers removed more than 10,000 works of art.”

Prison Time For Peter Max Faker

(photo courtesy:

John M. Smith)

Last week, a Connecticut court sentenced a man to prison for selling fake paintings being passed off as originals by the American pop artist Peter Max.

29-year-old Nicholas Hatch of Wilton, Connecticut, was arrested in May 2023 for selling one hundred forty-five fake Peter Max paintings. He pled guilty to mail fraud charges and was sentenced to repay the $248,600 to forty-three of his buyers. Hatch created a company in Norwalk called Hatch Estate Services, which would provide fake paintings to buyers through sites like estatesales.org. In December 2021, the FBI’s office in New Haven received a tip from a Hatch Estate Services employee, saying that they had discovered about one hundred fake Peter Max paintings in a warehouse in Bridgeport. This led to discovering Hatch’s scheme: he would apply paint over top of pre-bought Peter Max prints to imitate the color and the brushstroke patterns of real paintings. Genuine Peter Max paintings often sell in the $10,000 to $20,000 range. So when Hatch would sell his fakes for $1,300 and $2,900 each, the buyers must have thought they were getting a bargain. Hatch used multiple aliases and created several shell companies to help cover his tracks; some of the fakes even came with their own forged certificates of authenticity. He also kept the prints in multiple locations, mainly at warehouses and storage facilities. Investigators uncovered security footage at a self-storage facility in New Jersey, showing Hatch wheeling around a cart filled with dozens of framed prints. The scam ran from April 2020 to January 2022.

Peter Max has been in the news recently mainly because of legal issues concerning his children. For years, Libra and Adam Max have been trying to get rid of their father’s court-appointed legal guardian because of alleged abuse. Peter has been suffering from dementia due to Alzheimer’s for a little over a decade, and in 2015, he chose to have the court appoint a third-party legal guardian for him and his estate. The Max children allege that their father’s guardian has been trying to cut them off from their father and is siphoning money from the estate. However, the Max children’s efforts may have less to do with concern for their father and more about augmenting their share of their inheritance.

On Wednesday, April 17th, the Connecticut district court sentenced Hatch to 14 months in prison, which will begin on June 17th. After that, he must undergo three years of supervised release.

____________________

The Art Market

Christie’s Paris Impressionist : Oeuvres Choisies

Andre Derain

On Tuesday, April 9th, Christie’s Paris hosted the first Impressionist sale that will be all the buzz the rest of the week. They started with their “oeuvres choisies,” or select works, a collection of twenty-three paintings and sculptures from prominent nineteenth and twentieth-century European modernists like Sisley, Matisse, and Chagall. Unfortunately, no one could watch the sale online thanks to a technical malfunction with Christie’s Live, which the support staff seemed unable to fix for the entire forty-five-minute duration of the auction. I could record the results and calculate the hammer prices, but it didn’t really have the same excitement it normally would have. With these sorts of sales, a prominent Impressionist like Renoir usually claims the top. However, the Tuesday sale took a surprising turn. This time, it was Fauvism that stole the spotlight with André Derain’s painting Matisse et Terrus. Christie’s specialists seemed to understand the value of the work since it was the only lot valued at over €1 million. The painting was created when the three artists spent time with each other in the summer of 1905, at the height of the Fauvist movement. Matisse, along with Derain, was one of the leading Fauvist painters. Terrus, meanwhile, was mainly known as a landscape painter from the far south of France, near the border with Spain. Some may be more familiar with Terrus as the namesake of the Musée Terrus, which came into the news in 2018 after a visiting art historian concluded that over half of the museum’s contents may be fakes. Derain gifted the work to Terrus, whose descendants kept it in close to perfect condition for over a century. In terms of fauvist art, Derain’s paintings are definitely more rare compared to other artists like Matisse. The roughly 16-by-21.5 inch oil on canvas painting was predicted to sell for between €2 million and €3 million, with the hammer coming down at €2.6 million / $2.8 million (€3.19 million / $3.47 million w/p).

Immediately after the Derain came the second place lot, though few people would’ve guessed it. Christie’s specialists seemed to think that one of the Sisley paintings or perhaps the lone Pissarro might make it to the top three. However, it ended up being one of the sale’s two women who took second place. Françoise Gilot’s oil on panel painting Le Concert Champêtre, or Concert on the Green, is a rather large work, measuring 51 ¼ by 63 ¾ inches. Gilot created it in early 1953, during the final months of her decade-long romantic relationship with Pablo Picasso. The painting from Tuesday’s sale displays hints of Picasso’s style while remaining unique. Picasso experts say that the Spanish master assigned a different color to each of the important women in his life, with Gilot’s color being green. Christie’s assigned the Gilot an estimate range of €200K to €300K, with the hammer coming down at €1.05 million / $1.14 million (or €1.3 million / $1.43 million w/p). As I wrote several weeks ago, the Picasso Museum in Paris curated one of its gallery spaces dedicated to Françoise Gilot’s work, which commentators say is a significant step towards Gilot’s rehabilitation in France, where her reputation suffered immensely after her break with Picasso. In North America and, to some extent, the rest of Europe, Gilot’s popularity and reputation have remained mostly intact, with her work selling for far greater amounts at auction houses in London and New York. Le Concert Champêtre is now Gilot’s fourth most valuable painting and is by far the most valuable of her paintings ever sold in France. Not only is this one of the artist’s biggest moments at the auction block, but it may serve as a bellwether testifying to Gilot’s reputational rehabilitation in France.

Two lots were tied for third place, each selling for €550K / $598.3K (or €693K / $753.8K w/p). The first was one of the two Sisley paintings featured during the sale. Sisley painted Les Coteaux de La Celle, après Saint-Mammès in 1884, not long after moving to the Moret-sur-Loing area in the countryside just south of Paris. Like much of his work, Sisley focuses on the Seine, capturing its banks at Vernou-la-Celle-sur-Seine, just a few miles east of Fontainebleau. With a range of €400K to €600K, the Sisley fell nicely within its estimate. Meanwhile, the other lot sharing third was the single work by Rodin in the sale. Rodin originally exhibited the original marble sculpture Éternel printemps, or Eternal Springtime, at the Salon in 1897. After that, he created multiple versions cast in bronze, including this one, which he cast during his final years between 1916 and 1917. The sculpture has intrigued many, leading some to guess that the figures represent Cupid and Psyche, or perhaps they are personifications of the wind and the earth. It slightly exceeded the €300K to €500K estimate Christie’s assigned it.

The sale did incredibly well, with eleven of the twenty-three available lots selling within their estimates, giving Christie’s specialists a 48% accuracy rate. An additional three lots (13%) sold below, while eight lots (35%) sold above. Only one lot, an oil on canvas painting by Le Corbusier, went unsold, giving the sale a 96% sell-through rate. In total, the sale made €9.9 million, well within its presale estimate range of €7.39 million and €11.37 million. It’s important to remember that a quarter of the sale’s total came from the Derain painting.

“Filthy” Churchill Portrait Goes To Auction

The Roaring Lion (detail)

by Yousuf Karsh

A preliminary study of Winston Churchill’s least favorite painting will go to auction at Sotheby’s later this year.

When we think of famous portraits of Winston Churchill, the first one that comes to mind is the 1941 photograph by Yousuf Karsh, often called The Roaring Lion. It shows the prime minister as both dignified but also hardened, which is very appropriate for a world leader in the midst of a world war. The story goes that Churchill’s expression is because Karsh snatched the cigar out of his mouth after refusing to put it down. Modern audiences, however, might remember a different portrait of Winston Churchill, one painted by the modern British painter Graham Sutherland.

Parliament commissioned a portrait from Sutherland in honor of Churchill‘s eightieth birthday in November 1954. Some may be familiar with the painting since its creation was the subject of the ninth episode of season one of the Netflix series The Crown. John Lithgow won the Emmy for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series for his portrayal of Churchill in the episode.

At the time, Sutherland was one of Britain’s top contemporary artists; originally part of Britain’s Neo-Romantic movement along with Paul Nash and Ivor Hitchens, with his abstract landscapes being his specialty. His most well-known work, however, would come after the Second World War. He cemented his position as a leading artist with his 1946 painting The Crucifixion at St. Matthew’s Church in Northampton. The vicar, Walter Hussey, commissioned Sutherland at the recommendation of Henry Moore, who created a Madonna and Child sculpture for the church. Sutherland is said to have used photographs taken at Nazi concentration camps as references when creating the painting. By the late 1940s, he was also receiving commissions for portraits, including those of writer Somerset Maugham, politician and newspaper owner Lord Beaverbrook, gallerist Arthur Jeffress, and music critic Edward Sackville-West.

Winston Churchill had sat for portraits by several great artists at that point, including John Singer Sargent and Walter Sickert. So imagine his surprise when he saw the finished portrait for the first time, which was at its unveiling in Westminster Hall. Churchill was very self-conscious of his image and believed Sutherland’s portrait made him look decrepit and oafish. The painting’s admirers, however, saw Sutherland’s portrayal of the former prime minister not in a negative way but as a man weary from years of service to the country. His voice was dripping with sarcasm when he described the final portrait as a “remarkable example of modern art”. In private, Churchill described it as “filthy and malignant,” making him look like “a down-and-out drunk who has been picked out of the gutter in the Strand”; he never came to appreciate the portrait. Churchill’s wife Clementine hid it in the cellar of their home at Chartwell. Scholars generally agree that within a year of Churchill bringing the Sutherland portrait home, it was destroyed. Some say that Clementine took it into their yard and set it on fire, while others claim that Churchill’s private secretary, Grace Hamblin, did it.

During the portrait’s creation, Sutherland made a series of sketches and oil studies, which the artist later gave to the art dealer Alfred Hecht. One study belongs to the Ogilvy family, an aristocratic Scottish clan who are also King Charles III’s cousins. It differs from the final portrait in that it is only a bust-length portrayal in three-quarter view, with the former prime minister appearing a bit lost in thought. The Ogilvy family has consigned the study to Sotheby’s, where it will appear at the June 6th Modern British & Irish Art Evening Sale in London. Sotheby’s specialists estimate it will sell for between £500K to £800K. Before then, it will be on display at Sotheby’s New York location as well as Churchill’s birthplace at Blenheim Palace.

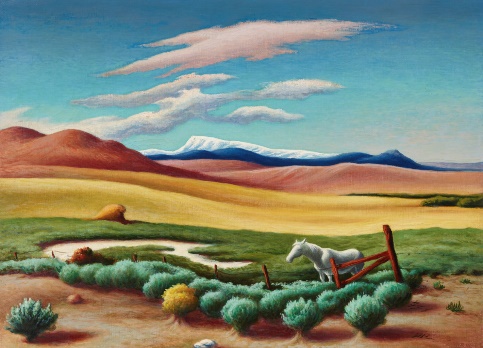

Christie’s New York Modern American Sale

Thomas Hart Benton

On Thursday, April 18, Christie’s New York hosted its modern American art sale, the first major auction dedicated to American art since January. The sale primarily featured paintings and sculptures by twentieth-century American artists like Milton Avery and Andrew Wyeth. Thomas Hart Benton, the most-represented artist at the sale, claimed the top spot with his 1955 oil painting White Horse. Originally from Missouri, Benton was captivated by the American West and made many Western landscapes in the 1940s. White Horse, a scene from rural Utah, is particularly rare since much of Benton’s Western landscapes are now in prominent museum collections. With an estimate of $1.5 million to $2.5 million, White Horse was eventually sold for $1.8 million (or $2.23 million w/p), a testament to its rarity and value.

Next up at Christie’s was the only Georgia O’Keeffe work featured at the sale. Blue Morning Glory is a fine example of one of O’Keeffe’s floral works. At the time of this painting’s creation in 1934, she was focused on flowers for about ten years. It’s a small work, measuring only 7-by-7 inches, and is one of four blue morning glory paintings O’Keeffe made between 1934 and 1936. But the painting’s scandalous provenance may have been another draw for buyers. Blue Morning Glory was previously owned by the Andrew Crispo Gallery, one of New York’s top modern and contemporary art galleries in the 1970s. However, Crispo became a tabloid fixture because of his hedonistic private life, including his involvement in the murder of a Norwegian FIT student in 1985, for which he was never charged. Blue Morning Glory exceeded its $1 million high estimate, landing at $1.4 million (or $1.74 million w/p).

Lastly, the third and final lot with a hammer price exceeding $1 million was Maxfield Parrish’s 1947 painting Ottaquechee River. By this point in his career, Parrish had made a name for himself as an illustrator and was turning to focus on serious landscape painting. This scene is set on the banks of the titular river in eastern Vermont, not terribly far from Parrish’s home in Plainfield, New Hampshire. Alma Gilbert-Smith, one of the leading experts on Parrish, declared Ottaquechee River one of Parrish’s thirteen greatest works. Though far from the artist’s auction record, the landscape hammered at a respectable $1.2 million (or $1.5 million w/p) against the house specialists’ $1 million to $1.5 million estimate.

Christie’s Modern American sale was full of surprises, with seventeen out of one hundred four available lots (16%) selling for more than double their high estimates. Four lots sold for more than five times their high estimate. Some of the most impressive surprises served as the auction’s bookends at the very beginning and the very end. The sale’s first lot, starting with a bang, was Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe’s Flowers (Gardenias in a Pitcher). O’Keeffe studied art with her older sister Georgia while growing up in Virginia, and she later went on to receive an MFA from Columbia University. During her lifetime, O’Keeffe often exhibited her work under the name Ida Ten Eyck to stay out of her sister’s shadow. She painted Flowers in 1932 on an 8-by-7-inch canvas. Ida O’Keeffe’s work has never sold for more than $15K at auction, but Flowers absolutely shattered her record, with the hammer coming down at $240K ($302.4K w/p) or over six-and-a-half times its $35K high estimate. Then, towards the end of the sale were two geometric abstract oil paintings by the Canadian-American artist Rolph Scarlett. White Triangle and Untitled are relatively large works, with Untitled, the smaller of the two, measuring about 43 by 43 inches. Both appear to have been influenced by European abstract artists like Kandinsky. Christie’s offered them without reserves and each were estimated at $7K to $10K. The two became Scarlett’s second and third most expensive paintings sold at auction, each selling for $70K (or $88.2K w/p), exactly seven times their high estimates.

Twenty-five of the one hundred four available lots sold within their estimates, giving Christie’s a 24% accuracy rate. Additionally, twenty-three (22%) sold below, while thirty-seven (36%) sold above. Nineteen lots (18%) went unsold, including the 1945 Milton Avery painting Female Painter, which Christie’s specialists picked as the sale’s star. In the same collection since 1995, Avery created Female Painter at the height of his career. The specialists predicted it would sell for between $1.5 million to $2.5 million. On top of Female Painter, there was also the Avery work Mother and Child by Seashore (est. $300K to $500K), Fairfield Porter’s Keelin Before the Reflected View No. 2 (est. $500K to $700K), Edward Hopper’s Oaks at Eastham (est. $500K to $700K), and Ralston Crawford’s Boat and Grain Elevator (est. $200K to $300K), all of which went unsold. These paintings getting bought in meant that Christie’s fell slightly short in terms of total dollar amount, bringing in $10.6 million (or $13.29 million w/p) against a pre-sale total minimum estimate of $10.8 million.

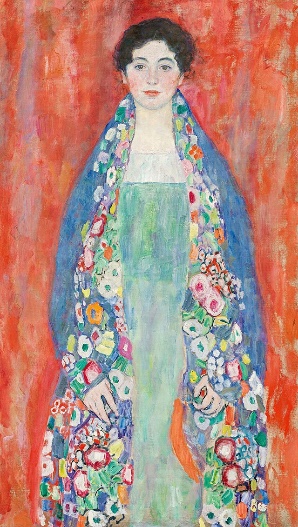

Lost Klimt Sells in Vienna

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser

By Gustav Klimt

On Wednesday, there was some auction news out of Austria. The country’s second-largest auction house, im Kinsky, had the art world’s eyes fixed upon it as it hosted a small sale that included several works by the Viennese fin de siècle painter Gustav Klimt. Of the nineteen works in the sale, everyone was mainly focused on the very last one: Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, one of the last great Klimt portraits left in private hands.

As I wrote back in January, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser was considered lost for over a century before being consigned to im Kinsky. Klimt created it in 1917, only a year before his passing. The portrait’s subject is unknown, but it is likely either Helene or Annie Lieser, sisters and members of the same wealthy Jewish family in Vienna. The Klimt’s current owners have had the painting in their family since the 1960s. Since there’s a gap in the ownership between the 1920s and when the seller’s family bought the portrait, there was initially some concern as to whether or not the painting’s provenance was tainted during the Second World War. Even though the Lieser family endured persecution at the hands of the Nazis, there is not much evidence to suggest that the painting was confiscated or sold under duress. To assuage any outstanding apprehensions, the current owners consigned Portrait of Fräulein Lieser jointly with the Lieser family’s descendants.

The auction consisted of only nineteen lots, with additional works by Klimt and other Austrian artists. Overall, the sale did okay, with thirteen of the eighteen selling, eleven within their estimates. The stars were two works by Egon Schiele, one from 1910 and the other from 1914. The earlier one shows his sister Gertrude seated, while the other is a kneeling female nude. Both were done with watercolor and black chalk on paper, with the nude featuring some gouache. The works sold for €600K and €750K, respectively, against their pre-sale estimate ranges of €600K to €1 million and €500K to €1 million.

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser was the sale’s final lot. Normally, a work with a multimillion-dollar estimate would attract several interested parties, provoking a bidding war. This, however, was not the case with the Klimt. After only a few bids, the hammer price was up to its minimum estimate of €30 million. The auctioneer held there for just over a minute before triumphantly bringing down the hammer, followed by the rapturous applause of the audience assembled there. The buyer ended up being Hong Kong dealer Patti Wong. Given Klimt’s popularity at auction and the story behind the painting, it’s confusing why the portrait did not go for more. However, it may be because of the outstanding concerns about the painting’s provenance. Erika Jakubovits, director of the Jewish Community Organization of Vienna, commented that there were still “many unanswered questions” surrounding the Klimt, particularly who possessed the work during the Second World War and the Holocaust. Im Kinsky concluded that there is not much evidence to suggest that the painting had been confiscated or sold under duress due to anti-Semitic persecution. Yet, the lack of evidence may have been enough to drive some potential buyers away.

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser became the most valuable painting ever sold in Austria, reaching the top ten of the most valuable Klimt works sold at auction. It took a day for im Kinsky to publish final prices with added buyer’s premium, which for the portrait came to €38.5 million w/p (or $41.15 million), taking the artist’s #7 spot. It came in right behind Kirche in Cassone, which sold at Sotheby’s London in 2010 for £26.9 million w/p (or $43 million w/p).

____________________

Deeper Thoughts

The British Museum Finally Sues

It’s been some time since I’ve written about the drama that began unfolding at the British Museum. last year. The last update I gave was in December when the museum’s deputy director resigned while an independent panel submitted a list of recommendations on changes to policy, security, and risk assessment. There’s been very little since then. But recently, the museum has taken a major step by formally naming the person they hold responsible for all this drama: former curator Peter John Higgs.

Those who have been keeping tabs on the scandal likely already know that, since the scandal broke in August 2023, British antiquities expert and former curator Peter John Higgs is suspected of having stolen thousands of antiquities from British Museum storerooms and archives. However, he hasn’t been named as the party responsible. Media sources deduced that Higgs was likely the museum employee accused since, in July, the museum fired him and his neighbors commented on the police presence at his house around the same time. But he has now been officially named in a lawsuit the British Museum is filing against him. The British Museum alleges that Higgs “abused his position of trust” as a senior curator to steal and/or damage thousands of antiquities for over a decade. At a hearing on March 26th, High Court judge Heather Williams ordered that Higgs return any museum items still in his possession within four weeks. Furthermore, the court has ordered that eBay and PayPal turn over the records associated with Higgs’s accounts, which would list the transactions for those stolen items he managed to sell online. Daniel Burgess, one of the British Museum’s lawyers, says Higgs also forged documents and manipulated museum records to sell these items. Higgs failed to attend the hearing due to poor health. He disputes the museum’s claims and denies any wrongdoing.

In addition to the British Museum’s lawsuit, there is also an ongoing police investigation. Higgs has not been charged with any crime so far. I suppose it’s good that the museum is relatively open about handling the situation. The scandal’s blow to the museum’s reputation means that everyone has to be on their best behavior. However, some have expressed their confusion as to why the British Museum is going through with legal action when it would not effectively do much. Martin Henig, an expert on gemstones who identified a stolen ancient Roman ring Higgs allegedly stole, described the lawsuit as “a case of locking the stable door after the horse has bolted”. Higgs has already lost his job, his reputation is in tatters, and most of the relevant information has already come to light. A civil suit would perhaps dredge up a bit of information but not anything substantial. The lawsuit could be seen, therefore, as a way to push complete blame onto Higgs despite that, according to Henig, “inevitably the institution bears some of the culpability for its negligence”.

The Tuesday hearing came two days before the museum named its new director to relieve interim director Mark Jones. Nicholas Cullinan, the former director of London’s National Portrait Gallery, will head the British Museum starting this summer. His tenure at the NPG saw the museum reopen last year after extensive renovations. The museum also acquired Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Portrait of Omai with the Getty Museum, as well as dropped British Petroleum as a sponsor of its annual portrait competition. Cullinan is said to have been selected with the “unanimous approval of the Board of Trustees and the agreement of the Prime Minister”. With a new director at the British Museum’s helm, hopefully the Higgs Theft can claim a legacy greater than some empty drawers and cabinets in the museum storerooms. Hopefully, this can herald a new era of greater transparency at one of the world’s greatest cultural institutions.

For previous updates on the British Museum’s Higgs Theft:

- August 18, 2023: The initial theft

- August 21, 2023: Higgs identified

- September 7, 2023: Identifying root causes

- October 24, 2023: Museum chairman and new interim director deal with the fallout

- December 20, 2023: Deputy director resigns; independent panel recommendations

California Confronts Courts With Proposed Art Law

Saint Honoré, apres midi,

effet de pluie

by Camille Pissarro

California state lawmakers are pushing through legislation that will make art restitution easier for Holocaust survivors. In January, I wrote about a restitution case going through the American court system for over twenty years. The case centers around a Paris street scene by Camille Pissarro, currently in the hands of Madrid’s Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, which a Holocaust survivor’s descendants are trying to have returned to them. In January, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Pasadena, California, ruled that the museum, owned and operated by the Spanish government, could keep the painting. Their reasoning comes from their application of Spanish law over California law. In Spain, if you buy stolen property but do so in good faith without knowing it is stolen, you can keep it. Upset by the court’s decision, some California state lawmakers are trying to prevent cases like these.

In the appellate court’s decision in January, the panel of judges unanimously decided, “We conclude that, under the facts of this case, Spain’s governmental interests would be more impaired by the application of California law than would California’s governmental interests be impaired by the application of Spanish law.” According to current California law, stolen property must be returned to its rightful owner regardless of the circumstances. However, under Spanish law, if a previously stolen artwork is displayed in good faith for at least three years, whoever possesses it legally owns it. The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum claims that they did not know that the Pissarro was sold under duress during the Holocaust. The descendants of Holocaust survivor Lilly Neubauer, who previously owned the Pissarro, dispute this.

To rectify the appellate court’s decision, on March 28th, state assemblymen Jesse Gabriel and Isaac Bryan, respectively representing California’s 46th and 55th assembly districts, introduced Assembly Bill 2867. The bill specifically pertains to the “recovery of artwork and personal property lost due to persecution” and would amend and add to the section of California’s Code of Civil Procedure relating to civil actions. It would specifically add to this section to specify that in cases where a California resident is involved in a civil suit “relating to title, ownership, or recovery of personal property […], California substantive law shall apply. This paragraph shall apply to all actions pending on the date this paragraph becomes operative or that are commenced thereafter, including any action in which the judgment is not yet final”. The bill also adds another paragraph specifying that a California resident may file a civil suit for damages pertaining to property “taken or otherwise lost as a result of political persecution.” According to Gabriel, “Respectfully, we think that the 9th Circuit got it wrong, and this law is going to make that crystal clear.” With the bill having bipartisan support, it shouldn’t be long before it makes its way through both houses of the state assembly.

Lilly Neubauer’s California-based descendants, who are involved in the lawsuit against the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, have expressed approval of the bill since its introduction this past Thursday. In the wake of the decision in January, the family filed for appeal. And with the new bill’s support, it won’t be long before the civil code’s latest additions will encounter their first test in the courts.

150 Years Of Impressionism

When the painter Gustave Caillebotte died in 1894, he bequeathed his entire art collection to the French state. In his will, Caillebotte expressed his wish that the seventy-three paintings be displayed at the Musée du Luxembourg before being transferred across the Seine to the Louvre. This provoked a furious outburst from the Académie des Beaux-Arts, with the academic master painter Jean-Léon Gérôme leading the charge against this collection of Impressionist works from being accepted by the state. When he heard that Monet and Pissarro paintings could grace the Louvre’s walls one day, he remarked, “For the state to accept such filth would be a blot on morality.”

Impression, soleil levant

by Claude Monet

As the executor of Caillebotte’s estate, Pierre-Auguste Renoir reached a compromise after three years of negotiations with government officials. The paintings considered the least objectionable, amounting to thirty-nine works, would be kept at the Luxembourg until curators could make space at the Louvre. When Paul Cézanne heard that two of his paintings were among those selected, he is said to have exclaimed, “Now Bouguereau can go to hell!” This was unimaginable just twenty-five years before. Impressionism went from outsider art to being displayed at France’s national museums. Caillebotte’s collection was promised a spot in the Louvre (where it was eventually transferred in 1927), marking the end of an uphill battle that Impressionist artists had fought for decades. And today marks one hundred fifty years since that battle first truly began.

2024 is the one-hundred-fiftieth year of Impressionism. Of course, Impressionism didn’t just emerge from Claude Monet’s skull fully formed. Impressionism developed among European painters after generations of innovations in technique and technology, changes in abstraction and appropriate subject matter, as well as the popularization of painting en plein air. I’ve previously written about what helped the Impressionists achieve their vision, including British landscapes, French neoclassical and Romantic painters, and the invention of collapsible paint tubes. Therefore, there isn’t a single day art historians point to and say, “This is the start of Impressionism.” However, certain dates were important in its development as an artistic style. One of those dates was April 15, 1874. This was when the First Impressionist Exhibition opened in Paris.

This exhibition was the first major challenge against the supremacy of the Salon. For centuries, the Salon was the place to have your work exhibited and judged. The Salon’s judges, members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, therefore became the arbiters of artistic taste in Europe and North America. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Salon’s status and reputation faced opposition from some artists. These nonconformists asserted that artistic taste is inherently subjective. Therefore, it hurts creative innovation to have a centralized organization of tastemakers unilaterally determining what is and is not good art. Many of these artists previously had their work rejected for exhibition by the Salon. Had the Salon judges been kinder, we may not have gotten what came next. Last year, I delved into how artists’ repeated objections led to the Salon des Refusés, an exhibition for those works rejected by the Salon. This was the first crack in the Salon’s status as the sole authority over artistic taste. At the time, some recognized these cracks forming, deciding that independent exhibitions would be the thing to tear down the Salon’s complete authority. Paul Cézanne’s friend Antoine-Fortuné Marion once remarked, “All we must do now is exhibit by ourselves and we will pose a deadly threat to those old, one-eyed idiots.”

To help support one another, some of these nonconformists got together to create their own organization that would act somewhat like a joint stock company and a mutual aid society. On December 27, 1873, they founded the Société anonyme coopérative des artistes peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs. Its members would pay dues to the organization set at 60 francs per year. Its founding members included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, and many others. However, there were some debates over who should be granted membership. Paul Cézanne became the subject of one such discussion. He was viewed as an outsider since he was the only prominent artist among them from the far south of France. Most founding members of the organization were Paris natives or from small towns just outside the capital. Edouard Manet probably had the greatest dislike for Cézanne, thinking of him as an uncouth southerner. Even though Manet declined membership in the organization, he was still consulted as to whether they should grant Cézanne membership. Camille Pissarro was the only artist of note to advocate for Cézanne’s inclusion. On the other hand, Degas suggested that they bring in established artists like Eugène Boudin, Félix Bracquemond, and Auguste Ottin to exhibit with them to bolster the group’s legitimacy. The group’s members approved of this idea but thought inviting outsiders would be inappropriate if they excluded one of their own. Cézanne was, therefore, allowed to join.

In 1874, the Salon would open on April 25th. To avoid it from overshadowing their show, they decided to open over a week earlier. The famous photographer Nadar allowed the group to use his old studio as their exhibition space at 35 Rue des Capucines, just a five-minute walk from the Madeleine Church. And so, on April 15, 1874, the First Exhibition, as they called it, opened to the public. On the walls were paintings like Edgar Degas’s The Dancing Class, the first of his ballerina paintings, as well as Impresion, soleil levant by Claude Monet. There were also seven works by Renoir, six by Sisley, ten by Morisot, six by Boudin, three by Cézanne, five by Pissarro, and three by Lépine. Close to two hundred visitors came on the first day. It was very small compared to the thousands the Salon would get, but it’s not nothing.

The Dancing Class

by Edgar Degas

To distinguish themselves from the Salon, the exhibitors created a more egalitarian environment in how they arranged and displayed their work. The Salon exhibitions were often held at some of Paris’s most spacious venues to accommodate as many works as possible. Between 1857 and 1897, that space was the Palais des Champs-Élysées, also known as the Palais de l’Industrie (which was demolished to make way for the Grand Palais and Petit Palais). The walls were often incredibly large, so they hung the paintings to fill an entire wallspace. The Academy judges frequently used this as a form of ranking. The works approved for exhibition but still deemed inferior to the others were placed higher up and, therefore, more difficult to see. However, Pierre-Auguste Renoir was responsible for arranging and hanging the works for the First Exhibition. He chose to display all the paintings and prints in no more than two rows, making it incredibly easy for viewers to study each work individually.

The reviews were not kind, yet it was these negative reviews that the exhibitors were collectively given their name: the Impressionists. The term “Impressionism” was originally an insult meant to deride the group, first found in the writings of journalist and art critic Louis Leroy. He wrote a review of the exhibition for the satirical newspaper Le Charivari on April 25th. Leroy took the term “Impressionism” from Monet’s painting Impression, soleil levant. Monet himself used the term “Impression” in the title to deflect criticism that the painting seemed incomplete. About Impression, soleil levant, Leroy wrote, “A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is better than this seascape!” Leroy had little better to write about the other paintings. In viewing Pissarro’s Hoarfrost, he described how his friend who attended with him “thought that the lenses of his spectacles were dirty. He wiped them carefully and replaced them on his nose.” He later lamented, “Oh, Corot, Corot, what crimes are committed in your name!” Another journalist, Jules Claretie, declared that the exhibitors had “declared war on beauty”. However, while “Impressionism” was initially used as an insult, the artists soon adopted the name for themselves.

The exhibition lasted for a month, attracting a few thousand visitors. In the aftermath, one of the few critics sympathetic to the Impressionists was Jules-Antoine Castagnary. He saw the use of the term “Impressionism” among his colleagues and thought it was a rather appropriate descriptor. He wrote in the newspaper Le Siècle, “They are impressionists in the sense that they render not a landscape but the sensation produced by a landscape.”

While some of the artists sold nothing at all, there was a spark of hope when Monet sold five paintings, including Impression, soleil levant, to the department store owner Ernest Hoschedé. Even though Nadar had let the Impressionists use his space for free, they still had to pay for advertisement, printing the catalogues, and redesigning the rooms as an exhibition space. When the Société Anonyme convened in December 1874, they found that they owed a little over 3,700 francs, meaning each exhibitor would have to chip in and pay the organization 184 francs. After settling this matter, the members unanimously agreed to liquidate the Société Anonyme. But despite the show being a critical and commercial failure, the Impressionists had made a name for themselves. They had gathered just enough interest to survive and paint another day, staging another exhibition in 1876. The Impressionists would put on eight exhibitions in total between 1874 and 1886.

While Impressionism to some today seems as old-fashioned as its academic predecessors, it became the first movement of modern art in the Western world. It was not only in their technique and subject matter but in how they helped decentralize the art world. They paved the way for scores of smaller salons and exhibitions, helping jumpstart the careers of generations of modernists in the twentieth century. They also helped people realize that deviating from the norm is okay. Without the Impressionists and their struggle against the Salon’s institutional conservatism, the world would have never known the primitivism of Henri Rousseau or the bright colors of Mattise and Derain. We wouldn’t have gotten Seurat’s little dots, Pollock’s splatters, Dada, absurdism, or surrealism. Regarding today’s art world, we may not have gotten installations, performance pieces, minimalism, pop art, hyperrealism, or the advent of street art and graffiti. Impressionism may be conservative by today’s standards, but that doesn’t mean we should disregard it. It was the jumping-off point from which all modern art began.

Art Institute Refuses To Give Up Mazi Loot

Russian War Prisoner

by Egon Schiele

The Art Institute of Chicago is putting up a fight regarding an Egon Schiele drawing that the Nazis possibly looted.

The museum has been one of the targets of the Manhattan DA’s office for some time now. The Art Institute, along with several other museums, has a drawing by the Austrian expressionist artist Egon Schiele, which the Manhattan DA’s office says was illegally taken by the Nazis from the collection of Austrian Jewish actor Fritz Grünbaum. The other museums have complied with the requests, while the Art Institute remains steadfast. When the DA’s office initially moved to confiscate the drawing in September, the museum put out a statement claiming they are “confident in our legal acquisition and lawful possession of this work.”

Seven months after the DA’s office made their initial move to seize the Schiele work, a drawing called Russian War Prisoner, the museum submitted a court filing claiming that there is no evidence whatsoever that the work in their possession was ever looted or stolen. This was a response to a filing the Manhattan DA’s office submitted in February, claiming that the Art Institute is actively ignoring the evidence that the Nazis stole the drawing. According to the facts, the Nazis imprisoned Fritz Grünbaum at Dachau, where he signed power of attorney over to his wife, who was then forced to surrender her husband’s collection. Authorities put the collection in a warehouse controlled by Schenker & Co., a logistics firm with extensive ties to the Nazi regime.

The Art Institute, however, claims that Russian War Prisoner passed legally from Grünbaum to his sister-in-law, who then sold it in 1956 to Swiss art dealer Eberhard Kornfeld. This was not the only work from Grünbaum’s collection that passed through Kornfeld’s hands. To buy into the Art Institute’s version of events, one has to believe Kornfeld’s story since he is the one who claimed that he bought the drawing from Grünbaum’s sister-in-law. The Manhattan DA’s office, however, is incredibly skeptical. In fact, their confiscation of stolen Schiele works is part of a larger investigation into Kornfeld and the gallerist Otto Kallir. Evidence suggests that the two of them sometimes dealt in artworks with tainted provenances, laundering the art by altering or covering up details. The DA’s office has pointed out that the provenance documents related to Russian War Prisoner contain alterations and forged signatures.

Furthermore, to bolster their claim, the Art Institute asserts that Schenker & Co. was a private company rather than a state-run organization, meaning that technically the Schiele was not taken by the Nazi government. And then there’s probably the boldest claim of them all, that Grünbaum had legally handed over power of attorney without any coercion. But of course, given that he was in a concentration camp, where he would end up dying in 1941, it would be an act of astonishing obstinacy to reject the reality that Grünbaum clearly had his assets taken from him under the guise of legality. In dealing with looted works previously in Grünbaum’s collection, a ruling from the New York State Court of Appeals states, “We reject the notion that a person who signs a power of attorney in a death camp can be said to have executed the document voluntarily.” Though there wasn’t a literal gun to his head, Grünbaum’s circumstances would nullify any legal action he took.

Many museums have already complied with the Manhattan DA’s requests, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Morgan Library, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Carnegie Museums, the Allen Memorial Art Museum, and several private collectors. In reality, most visitors to the Art Institute are not there to see any of Schiele’s works. They visit to see works by Grant Wood and Edward Hopper or to stand in front of A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat to reenact scenes from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. It’s interesting to speculate on why the Art Institute would make such a scene over one drawing, which is not even on display. The simplest and most likely answer is because of pride. It can be difficult to admit when you’re wrong, or you got fooled. However, sensitive topics like Holocaust loot are not the time to put on a brave face or stand defiant; nor come to the defense of the people who may have tricked you.

Pope Visits The Venice Biennale

The 2024 Venice Biennale has been one of the most memorable events in the art world this year thus far. Some of the highlights have included Archie Moore, an Aboriginal Australian artist, winning the Golden Lion award for the exhibition’s best film; Israeli artists have kept their country’s pavilion closed until a ceasefire can be reached in the ongoing Israel-Hamas war; and the city of Venice has implemented an entry fee for tourists visiting for the day. However, the most recent highlight was Pope Francis’s visit to the Biennale on Sunday, April 28th, the first time ever that a pope has attended the exhibition.

The Pope visited the Vatican’s pavilion, located in a women’s prison on an island in the Venetian Lagoon. He toured the pavilion’s exhibition, titled With My Eyes, which focused on themes of human rights, human suffering, marginalization, repentance, and regeneration. The first thing one sees after getting off the water taxi is Maurizio Cattelan’s black-and-white mural showing a pair of dirty feet. The Vatican’s culture minister, Cardinal José Tolentino de Mendonça, compared the mural to the bare feet of saints depicted in paintings by Caravaggio, while others made similar comparisons to Andrea Mantenga’s Lamentation of Christ. However, dirty, bare feet also represent charity and love in the Catholic tradition. Bishops, including the Pope, participate in the ritual washing of feet every year on Holy Thursday to emulate Christ washing his disciples’ feet. This comes from the gospel according to Saint John: “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. […] Most assuredly, I say to you, a servant is not greater than his master”. While previous popes have participated in this ritual, Pope Francis has stood out by not washing the feet of priests, as is normally done, but by performing the rite with lay people, including women and non-Christians. He made headlines one year after visiting a prison to wash and kiss the feet of inmates.

After exploring the exhibited works, Pope Francis shared his thoughts with the gathered artists and exhibition visitors. He spoke of the arts as a vital sanctuary for humanity. The Biennale’s theme this year, ‘Stranieri Ovunque’, or ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, resonated with him deeply. He urged the artists, saying, “I implore you, artist friends, imagine cities that do not yet exist on the map; cities where no human being is considered a stranger. This is why when we say ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, we mean ‘Brothers Everywhere’.” He also had the opportunity to meet some of the prison’s eighty inmates, who had contributed to the exhibition by composing poetry on the walls.

Following his visit to the Vatican pavilion, the pope stopped by the Basilica della Salute before saying mass in the Piazza San Marco to a crowd of 10,000. He commented on the city’s beauty without ignoring its serious problems, most notably climate change and overtourism. Despite his poor health in recent months, many who were present with the Pope noted his energy and enthusiasm during the visit.

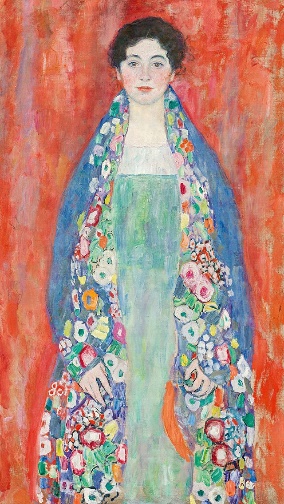

Possible Heir Claims Klimt Portrait

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser

By Gustav Klimt

A significant Gustav Klimt portrait has become the subject of an ownership dispute after a German man said it was his.

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser by Gustav Klimt sold at the Vienna auction house im Kinsky last week for €30 million / $32 million (or €38.5 million / $41.15 million w/p). The auction house specialists anticipated the painting to sell for as much as €50 million. However, some suspect that questions surrounding the portrait’s provenance may have scared away many potential buyers. The painting previously belonged to a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna, many of whose members died in the Holocaust. Between 1925 and the 1960s, ownership of the painting was mostly a matter of speculation. Im Kinsky reassured everyone that there is no evidence that the painting illegally changed hands during the Second World War. To quell residual fears, the family who owned the painting for the past fifty years consigned the work jointly with several of the Lieser family’s descendants. Despite news of the portrait’s recovery making the rounds back in January, it wasn’t until the day before the auction that a man in Germany claimed ownership of the painting.

According to a report in the Austrian newspaper Der Standard, the claimant, an architect in Munich, is likely not related to the Lieser family, yet that has not stopped him from making claims that he is the legal heir of Adolf Lieser, father of the portrait’s likely subject, Margarethe Lieser. Negotiations are currently underway involving all the interested parties. Even if this new claimant was a member of the Lieser family, there’s the matter of im Kinsky’s contract, which states that the descendants who consigned the Klimt did so on behalf of themselves as well as all possible heirs. Hong Kong art dealer Patti Wong, who bought the painting on behalf of an anonymous collector, said that she was assured this was the case. Im Kinsky’s contract further states that a new claim has no bearing on the validity of last week’s sale. From what is currently known, this latest challenge seems unlikely to succeed. However, we don’t know what information or evidence may come to light in a legal battle like this.

The Rehs Family

© Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York – April 2024