COMMENTS ON THE ART MARKET

New Artist

Ryan S. Brown was born and raised in Salt Lake City, Utah. By his senior year in high school, Ryan had decided to pursue art as a profession. This pursuit led him to Brigham Young University, graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 2002. He studied classical painting in Florence, Italy, at the Florence Academy of Art, where he won the Painting of the Year and Presidents awards upon graduation. Ryan returned to the US in 2008 and opened the Masters Academy of Art in Springville, Utah, where he teaches the methods and practices within the tradition of classical painting.

Ryan was the top award winner of the John F. and Anna Lee Stacey scholarship in 2004. He also received third place in the Art Renewal Scholarship competition in 2005. In 2006, Ryan was one of ten artists to be invited by American Artist Magazine to the Forbes Trinchera Ranch for a 10-day retreat. His work was featured in a special exhibition at the Forbes Gallery in New York the following year. In May 2008, Southwest Art magazine named Ryan "A Rising Artist to Watch." That was the same year he won the "Painting of the Year" and the President's Award at the Florence Academy of Art.

Several paintings by Ryan will be on view at the Newport and Nantucket shows.

____________________

Upcoming Shows

Nantucket

Coming real soon, like next weekend, The Nantucket Show. We have a limited number of complimentary General Admission tickets. If you would like to attend, please email us as soon as possible:

Hours

Preview Party: Thursday, August 3:

Friday: August 4: 10am – 6pm

Saturday: August 5: 10am – 6pm

Sunday: August 6: 10am – 5pm

Monday: August 7: 10am – 3pm

Location

Nantucket Boys and Girls Club

61 Sparks Avenue

Nantucket, RI

____________________

Stocks & Crypto

By: Lance

The month isn’t quite over just yet, but my father is super impatient so here we are… these numbers are as of close on July 28th. Pleasantly, we saw positive movements across the three major indexes – the DJIA gained 3.16%, the NASDAQ is up 3.75%, while the S&P climbed 2.96%. Much of the concern expressed by the markets earlier this year seems to have eased up, particularly with respect to economic growth and inflation. With that, there has been more of an appetite for riskier assets. Further, at the start of the month, the Fed believed there was more than a 70% chance the US would fall into a recession within the next 12 months… as of this past Wednesday, the Fed is no longer forecasting a US recession. Woo! We did it! Maybe?

As for currencies and commodities… the Pound strengthened against the dollar though it has retreated some in the past week, now trading at $1.28; the Euro followed the same pattern and is currently at $1.10. Gold has continued to climb through the month and is back to flirting with $2,000… it sits just shy at $1997.90, which was a gain of more than 4% in July. Similarly, crude steadily ascended past $80, gaining more than 14%; its highest point since April.

Crypto was a bit of a mixed bag and not as volatile as some other months. Bitcoin was actually down a bit… it slid 2.8%, now trading at $29.2K, but seems to have stabilized in this new trading range around $30K. At one point, Ethereum was up more than 10% and crossed the $2K threshold, but finished things off with a modest 2.2% gain for July at just $1,873. Litecoin saw the most action… in the first week of the month it popped more than 40%, but gave up much of those gains over the following weeks – still, it closed out with a solid 11.5% gain.

Overall, July was generally positive with momentum trending in the right direction. While we still may see a slowdown in growth later in the year, it seems like a reasonable possibility inflation will return to normal levels without high levels of job loss.

____________________

Collecting

By: Amy

A ”Brush” With History

As many of you know, we specialize in the works by Antoine Blanchard (born Marcel Masson, 1910 – 1988), the renowned artist known for his exquisite Parisian street scenes. When we first started selling works by Blanchard, we noticed that 1 out of every 8 to 10 paintings found in the market are actually by “The Antoine Blanchard.” Thus, we began a research project focused on his life and work. We wanted to ‘clean up’ the market so people would be aware of the authenticity of the pieces they were purchasing; our research enabled us to create the Antoine Blanchard Catalogue Raisonné. We are now considered the experts on Blanchard and receive submissions for paintings to be authenticated almost daily. Unfortunately, for many, the authentications will not be in their future.

As many of you know, we specialize in the works by Antoine Blanchard (born Marcel Masson, 1910 – 1988), the renowned artist known for his exquisite Parisian street scenes. When we first started selling works by Blanchard, we noticed that 1 out of every 8 to 10 paintings found in the market are actually by “The Antoine Blanchard.” Thus, we began a research project focused on his life and work. We wanted to ‘clean up’ the market so people would be aware of the authenticity of the pieces they were purchasing; our research enabled us to create the Antoine Blanchard Catalogue Raisonné. We are now considered the experts on Blanchard and receive submissions for paintings to be authenticated almost daily. Unfortunately, for many, the authentications will not be in their future.

Blanchard captured the essence of Paris in a unique and captivating way; let’s just say he had a “brush” with history! Though he was mainly a painter of the postwar era, he could transport himself back in time and capture the essence of Paris during the Belle Époque. His works showcase the bustling streets of Paris, the picturesque boulevards, the iconic landmarks, and the everyday life of its residents.

Over the years, the value of Antoine Blanchard’s paintings has steadily increased. The demand for his works, particularly those depicting well-known Parisian locations such as the Champs-Élysées or the Moulin Rouge, has contributed to their market desirability.

Many people believe that buying at auction can save you money compared to purchasing from a reputable gallery. However, this may not always be the case. At a recent auction, a typical 13 x 18-inch painting by Blanchard featuring the Arc de Triomphe sold for $10,625. However, the painting needed to be re-framed and required cleaning, which could cost an additional $1,500 or more, and do not forget the shipping costs. In June, a painting depicting Place de la Concorde sold for over $13K and also needed additional work before it was ready to be hung. When you buy from a gallery, everything is already taken care of — the painting is ready to be enjoyed.

____________________

The Dark Side

By: Nathan

Forger’s Fall: Pasquale Frongia Arrested in Italy

The Italian Carabinieri have arrested one of the most notorious Old Masters forgers in the world. Pasquale Frongia is allegedly one of the most important members of an Old Masters forgery ring put together by art dealer Giuliano Ruffini. Authorities suspect Ruffini of having had a hand in art forgery for about three decades, having sold Old Masters forgeries to many of the world’s top museums and galleries. Ruffini, his son Mathieu, and Frongia allegedly made about $220 million from selling Old Master forgeries across Europe and the United States, passing them off as originals by Parmigianino, Frans Hals, and El Greco, among others. Most notably, he is alleged to have sold a forged Venus painting that he passed off as being by Lucas Cranach the Elder. In a matter of months, the forged Cranach made its way to the Colnaghi Gallery and eventually to the private collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein. This caused a bit of a scandal when French authorities confiscated the Prince’s Cranach as part of the investigation. Ruffini himself was arrested last November on charges of fraud and money laundering. He is currently under house arrest awaiting trial.

The Italian Carabinieri have arrested one of the most notorious Old Masters forgers in the world. Pasquale Frongia is allegedly one of the most important members of an Old Masters forgery ring put together by art dealer Giuliano Ruffini. Authorities suspect Ruffini of having had a hand in art forgery for about three decades, having sold Old Masters forgeries to many of the world’s top museums and galleries. Ruffini, his son Mathieu, and Frongia allegedly made about $220 million from selling Old Master forgeries across Europe and the United States, passing them off as originals by Parmigianino, Frans Hals, and El Greco, among others. Most notably, he is alleged to have sold a forged Venus painting that he passed off as being by Lucas Cranach the Elder. In a matter of months, the forged Cranach made its way to the Colnaghi Gallery and eventually to the private collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein. This caused a bit of a scandal when French authorities confiscated the Prince’s Cranach as part of the investigation. Ruffini himself was arrested last November on charges of fraud and money laundering. He is currently under house arrest awaiting trial.

Frongia was arrested previously in relation to the Ruffini ring in 2019. French authorities have investigated the Ruffinis since 2014 and issued arrest warrants for Ruffini and Frongia. However, a court in Bologna declined to extradite them because, to them, the charges were inconsistent. One of the main pieces of evidence connecting Frongia to the Ruffinis is a series of money transfers Frongia received from Mathieu Ruffini, including one for about $740,000 from a UBS Swiss bank account. Despite Mathieu claiming not to know anything about his father’s business, Frongia claims that this money was payment for restoration work he did on behalf of Ruffini. Mathieu was arrested along with his father but is now out on bail. Giuliano Ruffini has disputed the forensic evidence that investigators used to prove the paintings he sold are modern forgeries.

Neapolitan Inferno: Public Art Set On Fire In Italy

Venus of the Rags is a sculpture by contemporary Italian artist Michelangelo Pistoletto. It consists of a classical-style sculpture of the Roman goddess Venus standing before a pile of discarded clothing. Two weeks ago, Pistoletto erected a large-scale version in the Piazza del Municipio in Naples as a part of the city’s efforts to support the arts called Napoli Contemporanea. But last Wednesday, passersby were surprised to find the work engulfed in flames. Someone had set it on fire.

Venus of the Rags (or Venere degli stracci in Italian) was first created in 1967. Since then, Pistoletto has made several versions of the sculpture, including those at the Tate and Washington DC’s Hirshhorn Museum. The work is full of dichotomies. There’s the plain, pure white against a multicolored heap; the hard, sturdy statue against soft, pliable clothing; the ancient alongside the modern; the meticulously preserved with the easily discarded. It is an example of Arte Povera, or Poor Art, an Italian artistic movement popular during the late 1960s and early 1970s, of which Pistoletto was a central figure. The point was to create art using simple, everyday objects. But even the statue of Venus is as modern, available, and disposable as the rags. Though Pistoletto based the Naples version on Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Venus with the Apple, the original 1967 version used a simple concrete Venus statue he found at a gardening store. But publicly displaying a version in Naples is appropriate since many have interpreted the work as a commentary on the city’s history and current status. Naples has always been far poorer than its northern counterparts like Milan, Turin, and Venice. Despite its great history, persevering throughout the millennia since its foundation as an ancient Greek colony, poverty, organized crime, and political corruption are still serious problems that plague Naples today.

The day after the incident, police arrested a 32-year-old homeless man on suspicion that he may have been involved. His motivations are not known. The mayor of Naples, Gaetano Manfredi, stated, “I have already heard from Pistoletto, the work will be redone. Violence and vandalism will not stop art, regeneration, and culture in Naples.” Meanwhile, local politician Piercamillo Falasca has called for a public fundraiser to fund these efforts.

The New Shein Lawsuit

A while back, I covered an incident where the Chinese fast fashion retailer Shein found itself in a spat with the British artist Vanessa Bowman. The company had used an image of one of Bowman’s paintings on a sweater without her express permission. At the time, this was only the latest instance of Shein clearly stealing the works of artists to use on clothing, stickers, posters, and other products available for purchase online. The most common way artists exposed this ongoing problem was by stirring up public outcry on social media. The Artists’ Union, an organization representing hundreds of artists in Britain, has endorsed such actions. Only large companies with well-known, copyrighted logos and images attached to their name have been the ones willing and able to go through with legal action. However, a group of artists has recently banded together to sue Shein, using an interesting legal strategy. They intend to hold the company accountable by using legislation meant to counter organized crime.

A while back, I covered an incident where the Chinese fast fashion retailer Shein found itself in a spat with the British artist Vanessa Bowman. The company had used an image of one of Bowman’s paintings on a sweater without her express permission. At the time, this was only the latest instance of Shein clearly stealing the works of artists to use on clothing, stickers, posters, and other products available for purchase online. The most common way artists exposed this ongoing problem was by stirring up public outcry on social media. The Artists’ Union, an organization representing hundreds of artists in Britain, has endorsed such actions. Only large companies with well-known, copyrighted logos and images attached to their name have been the ones willing and able to go through with legal action. However, a group of artists has recently banded together to sue Shein, using an interesting legal strategy. They intend to hold the company accountable by using legislation meant to counter organized crime.

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, commonly referred to as RICO, is a law meant to combat organized crime and its infiltration of legitimate businesses. The law has been successfully implemented in prosecuting John Gotti and Hells Angels members. Luckily for the artists, copyright infringement is one of the crimes listed as a form of racketeering, which the lawsuit describes as “large-scale and systematic” in Shein’s case. Artists Krista Perry, Larissa Martinez, and Jay Barron are the plaintiffs named in the lawsuit, alleging that not only did Shein steal their designs for use on products available online but that Shein’s corporate structure is intentionally designed to deflect blame and avoid the company being named as a defendant in any legal action. The artists’ lawyers called the company a “decentralized constellation of entities, designed to improperly avoid liability.” Shein is neither a single company nor a parent company with subsidiaries or independent contractors. According to the lawsuit and other sources, Shein is “a loose and ever-changing […] association-in-fact of entities and individuals”. Researchers and journalists can attest that when confronted with intellectual property cases, Shein often defers to other businesses they claim do their design or production for them. However, it is now known that these seemingly third-party companies are shell corporations Shein operates to absorb their legal woes. The collection of companies popularly known as Shein is intentionally decentralized so that blame cannot be definitively placed on one part.

Krista Perry is an illustrator and designer who has previously done work for Jameson Irish Whiskey and Nickelodeon. One of her designs, the stylized phrase Make It Fun against a pink background, was made by Shein into a framed poster. Larissa Martínez operates the handmade clothing brand Miracle Eye, and found that her marigold-patterned shorteralls were being copied and sold on Shein’s website. Jay Baron mainly designs stickers and patches through his company Retrograde Supply Co., including a patch based on a nametag called Trying My Best. He later discovered products available on Shein that were practically identical.

Outside of intellectual property theft, Shein’s reputation is still terrible. The company’s working conditions are notorious, with allegations including 75-hour shifts, incredibly unhealthy, dangerous workspaces, and the use of hazardous materials. Some factories have even been accused of using underage or forced labor. Shein’s environmental record is equally abhorrent, with their factories alone emitting around 6.3 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. And their attempts to clean up their image before their imminent initial public offering have failed. Recently, Shein invited a select group of social media influencers and content creators to tour factories in China. This was to show how well their workers were faring and how content they were with their employment. However, many people saw this ploy for what it is: a modern-day Potemkin village; like when you straighten up your place when you know you’re having people over. Things seemed set up or staged especially for these foreign visitors as a way to deny the insurmountable pile of evidence that will contradict this sorry excuse of a defense. One Twitter user responded, calling the featured facility “the model unit equivalent of the sweatshops”. Some have even predicted that while Shein’s future as a company remains unclear, these young influencers/creators will most definitely receive negative feedback for years to come because they decided to involve themselves in a propaganda campaign. One of the influencers on the trip even pitched the tour as her doing a bit of investigative journalism, as if anything seen in her content was objective or fact-based.

Luckily, about two dozen members of Congress have called upon the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) to delay Shein’s IPO until they fully investigate the allegations against the company. Specifically, Shein allegedly uses forced labor provided by imprisoned Uyghur people in western China. The new lawsuit brought by Perry, Martínez, and Baron may not be the single thing that holds Shein accountable, but it may be the first domino that leads to a more thorough investigation into the company. Hopefully, by the end of this, we can all know the full extent to which Shein has destroyed the environment, exploited its workforce and stolen from independent artists too small to fight back.

____________________

The Art Market

By: Nathan

Christie’s London Impressionist & Modern Art Sale

On Friday, June 30th, Christie’s London hosted a sale of impressionist and modern art, featuring a wide variety of works from Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot through Carlos Nadal and Charles Malle. Many of the lots were works by late-nineteenth and twentieth-century modernists, with four by Emil Nolde and Joan Miró, five by Salvador Dalí and Maurice Utrillo, and six by Maurice de Vlaminck. There were also twelve lots by the Russian-French painter Marc Chagall, one of which was a series of 42 lithographs. Entitled Daphnis et Chloé, Chagall executed the series between 1956 and 1961 and was valued between £700K to £1M by Christie’s specialists, making it the highest-valued lot in the sale. The series shows the story of Daphnis and Chloe, a Roman romance based on characters from Greek myth. Though the series fell slightly short of its minimum estimate, with the hammer coming down at £650K / $822.1K (or £819K / $1M w/p), it remained the most expensive lot in the sale. Six lots later, the painting Course de taureaux by Moïse Kisling came across the block. Christie’s expected the bullfight scene to do well, so they displayed it directly behind the phone bank in the London saleroom. Like the Chagall series, the Kisling was highly-valued, estimated to sell between £400K and £600K. Also like the Chagall, momentum puttered out slightly before hitting the minimum estimate, selling for £375K / $474.3K (or £472.5K / $597.6K w/p).

Four lots achieved the same third-place hammer price of £260K / $328.8K (or £327.6K / $414.3K w/p). Two lots were more works by Chagall, both featuring flowers alongside young couples. While Bouquet de fleurs et amoureux is oil paint on canvasboard created in 1978, Le bonheur du jeune couple aux fleurs is a gouache and ink work on paper made in 1967. While the former has a relatively short provenance, having only one owner after being purchased from the Marescalchi Gallery in Bologna, Italy, the gouache work is much more well-traveled. Since its creation, Le bonheur du jeune couple aux fleurs has been owned by galleries and collectors in France, the United States, and Sweden. The first and most recent time the painting sold at auction was when a Swedish collector sold it through the Uppsala Auktionskammare, where it sold for a hammer price of 3.1 million Swedish kronor, or about $300K. It seems its new owner was rushing to get rid of the painting since the Swedish auction only took place on May 11th of this year. Among the other £260K works was a charcoal and pastel drawing by Edgar Degas entitled Femme nue s’essuyant. The work last sold at Christie’s New York in 2010 for $320K, meaning the now-former owner lost about $60K due to having to pay the buyer’s premium thirteen years ago. The last of the four third-place works was a 30-inch-high bronze Rodin sculpture Eve, petit modèle, which, like the Degas, suffered a loss compared to the last time it sold at auction (back in 2016, Eve sold at Christie’s Paris for €575K, or $654.9K at the time).

Despite its successes, the sale was bittersweet for Christie’s. With fifty-seven of the one hundred fifty-six available lots selling within estimate, the Christie’s specialists walked away with a 37% accuracy rate. Twenty-nine lots (19%) sold below their estimates, while twenty-one (13%) sold above. This left forty-nine lots (31%) unsold, including several highly-valued works. These included the Gustave Caillebotte seascape Les toits de l’Hôtel des Roches Noires, Trouville (est. £500K to £800K), the August Macke gouache and watercolor painting Nackte Mädchen in der Barke (est. £250K to £400K), and René Magritte’s portrait of Madeleine Goris (est. £180K to £250K). Because of the number and value of the lots bought in, the entire sale had a total hammer of £7.3M / $9.2M against a minimum total estimate of £10.5M.

Sotheby’s Old Master & 19th Century Paintings

Last week, the Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Bonhams London salerooms hosted a series of Old Masters sales across three days. One of the more memorable sales occurred on Wednesday, July 5, when Sotheby’s hosted an Old Masters and Nineteenth-Century paintings sale in the evening. The forty-nine available lots ranged from fifteenth-century religious icons, Dutch still-lifes, Tudor-era English portraits, and a few nineteenth-century landscapes for good measure (w/p = with buyer’s premium). All three of the most valuable pieces came early in the sale, within the first eleven lots. At the very top was a religious oil on panel painting created around 1490 in what is now Belgium. The subject is a scene from the New Testament, showing Christ’s disciples celebrating Pentecost when the Holy Spirit descended upon them, represented by the flaming dove above them. Despite the biblical story, the apostles gather in a room that would look more familiar in fifteenth-century Belgium than in ancient Judea. The creator of the painting is unknown, but art historians have identified works of a similar style, leading them to give this anonymous artist the nickname Master of the Baroncelli Portraits. Sotheby’s specialists traced the work’s provenance back to around 1600 when it first entered the Rapaert family collection; they owned the painting until 1931. It last sold at Christie’s London in 2010 for £3.7M (or about £5.4M / $6.9M today), and this time, Pentecost hit its low estimate at £7M / $8.9M (or £7.9M / $10M w/p).

The two remaining top lots both ended up selling for £4.2M / $5.3M (or £5.1M / $6.5M w/p). The first was the oil on panel painting Virgin and Child with the infant St. John the Baptist, St. Francis, and St. Catherine of Siena by the Italian Mannerist Domenico Beccafumi. The last time this painting saw the inside of an auction house was in 1928, when it sold as part of an estate sale at Berlin’s Kunst-Auctions-Haus. Back then, it sold for 3,500 Reichsmarks, equivalent to $14,785 today. The work was estimated to sell between £3M and £4M, putting its final hammer price slightly above the maximum estimate. Meanwhile, selling for the same hammer price was Saint Sebastian tended by two angels by Peter Paul Rubens. The painting shows the titular saint when he was shot full of arrows during his martyrdom. The work has an extensive provenance, having been in the same aristocratic Italian family collection between 1600 and 1733, before making its way to, of all places, St. Louis, Missouri. The Rubens graced the block of the St. Louis auction house Ivey-Selkirk more than once, where the now-former owner acquired it in 2008. Since 2010, it has been on loan to the Rubenshuis in Antwerp, the museum containing Rubens’s house and workshop. However, it is unknown if the new owner will continue this loan. The former owner, who bought it in St. Louis, made a good chunk of change from the sale since he purchased the work for only $32K due to it being misattributed to Rubens’s French contemporary Laurent de La Hyre. Saint Sebastian was given an estimate range of £4M to £6M, with the hammer falling just above the minimum.

The sale also included several surprises, the most noteworthy of which was a portrait of Queen Katherine Parr, the sixth and final wife of King Henry VIII of England. The portrait was likely created around 1548, shortly after the king’s death. It is one of only two surviving contemporary portraits of the queen, and both are attributed to an English portraitist known only as Master John. However, the artist’s identity is a relatively recent discovery. The portrait was sold at auction five times over the past two hundred years. The records from those sales indicate that specialists have not always attributed the work to Master John, and that they did not always identify the portrait’s subject as Katherine Parr. When it sold at auction in 1829, 1831, and 1841, the work was described as a portrait of Queen Mary I attributed to the Flemish painter Lucas de Heere. Previously, in 1827, Christie’s attributed the work to the portraitist Antonis Mor, while later, in 1848, they described it as being by Hans Holbein. It wasn’t until 1996 that Susan James finally identified the subject as Katherine Parr after looking at the queen‘s jewelry. On the front of her dress is a brooch featuring a crown on top and three pearls hanging from the bottom. This matches the appearance of the Coronet Brooch, known to have been part of Katherine Parr’s jewelry collection and featured in Master John’s other portrait of the queen now on display at the National Portrait Gallery in London. The portrait was probably the day’s biggest surprise, with bidding extending far longer than anticipated. Expected to sell for between £600K and £800K, the portrait of Katherine Parr eventually sold for £2.8M / $3.5M (or £3.4M / $4.3m w/p), or three-and-a-half times the high estimate.

Of the forty-nine available, fifteen sold within their estimates, giving Sotheby’s specialists a 31% accuracy rate. Another nine lots (18%) sold below estimate, while eight (16%) sold above. Unfortunately, seventeen lots (35%) did not meet their reserves and went unsold, including the highly-valued seascape A Calm Sea by the Dutch Golden Age painter Jan van de Cappelle, estimated to sell for between £800K and £1.2M. The sheer number of unsold lots caused the sale to make slightly less than expected, bringing in £32.7M / $41.5M against a total pre-sale estimate of £34.8M to £49.4M.

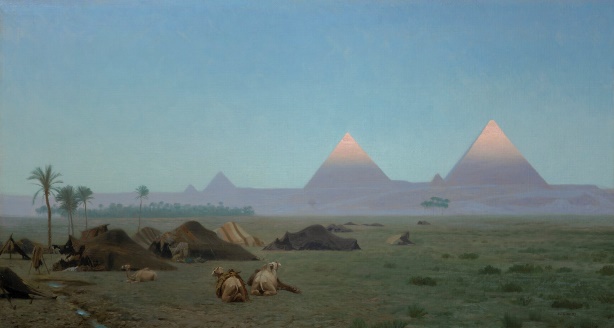

Christie’s London British & European Art

On Thursday, July 13th, Christie’s London hosted its British and European Art sale, featuring over a hundred works, including those by Edward Seago, Terrence Cuneo, and Dame Laura Knight. However, the Orientalist and sporting scenes grabbed the most attention (w/p = with buyer’s premium). The sale’s top lot was The First Kiss of Sun by the Orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme. Created in 1886, the landscape shows the Pyramids of Giza at dawn. The viewer is turned away from the rising sun and instead looks westward, where the day’s first light is streaming over and hitting the very tops of the pyramids. Meanwhile, a camp of tents lies asleep, accompanied by their resting camels under a small group of palms. Gérôme created this landscape later in his career when recovering from a bout of influenza. It last sold at Christie’s London in 2003 for £260K. It last sold at Christie’s London in 2003 for £260K. It seems Christie’s specialists believed that the market for Orientalist landscapes, or Gérôme’s work in particular, is in a similar place since they gave the work an estimate range of £250K to £350K. The First Kiss of the Sun eventually sold at its low estimate of £250K / $327K (or £315K / $412K w/p).

Right behind the Gérôme were two equestrian scenes, both by the British painter Sir Alfred James Munnings. The first shows a pair of children on their horses accompanied by dogs. According to the inscription on the back, they are the siblings Honor Smith and Hugh Smith, riding their horses at Weald Hall in Essex. The siblings were the youngest of Vivian Smith’s seven children. In 1919, at the time of the painting’s creation, Vivian Smith was the governor of the Royal Exchange Assurance Corporation, which at one point served as the British government’s exclusive marine insurance provider. Honor would later study medicine, becoming a professional neurologist specializing in treating tuberculosis meningitis. Meanwhile, Hugh joined the British Army and saw combat in Italy during the Second World War. He became a captain in the Irish Guards and was even temporarily promoted to major. Christie’s gave the equestrian double portrait the same estimate as the Gérôme, which it just barely missed, with the hammer coming down at £240K / $313.9K (or £302.4K / $395.5K w/p). The third-place lot was a more typical Munnings work. Who’s the Lady? is an oil on canvas painting measuring about 44 by 70 inches showing the moments before an aristocratic English foxhunt. All the men are upon horses and dressed in bright red jackets while a pack of hunting dogs scurries about. Several men are doffing their hats and bowing to the painting’s subject, a lady in black sitting side-saddle upon a gray horse. Like some of the men in the scene, the viewer is left wondering the title question: who is she? Munnings reveals her identity in the inscription on the back of the canvas. She is Princess Mary, who at the time was Princess Royal, the sister to kings Edward VIII and George VI, and the aunt of Queen Elizabeth II. Christie’s also offered Who’s the Lady? along with two studies, one on board and the other on panel. The painting itself has not been up at auction since 1979, while the studies both last sold in 1981. Against a £150K to £250K estimate, Who’s the Lady? and its two studies sold for £180K / $235.4K (or £226.8K / $296.6K w/p).

Along with these successes, there were also several surprises throughout the sale. The Caravan by Josef von Brandt shows a group of mustachioed horsemen armed with rifles and whips guarding several camels loaded with merchandise. It is unknown where or when this scene is set, but the horsemen’s clothing and the inclusion of camels might narrow it down to West Asia, the Caucasus, or Russia. This is a bit of a departure from Von Brandt’s more recognizable work, which often featured either battle scenes or depictions of Polish peasant life. The last time The Caravan sold at auction was at Christie’s London in 1998 for £32K, far above its £12K high estimate. Again Christie’s underestimated The Caravan, expecting it to sell for no more than £50K, yet it ended up making £170K — more than three times that number. Two lots later, there was Eugene Alexis Girardet’s Flight into Egypt. Similarly to The Caravan, Girardet’s Flight into Egypt exceeded expectations the last time it came across the block. It last sold in 2014 at the Cologne auction house Lempertz for €46,360 against a €12K high estimate. This time, Christie’s gave the Girardet a £15K high estimate, which it quickly exceeded, reaching exactly three times that number at £45K / $58.8K (or £56.7K / $74.1K w/p).

Of the one hundred twelve lots available, thirty-two sold within their estimates, giving Christie’s specialists a 29% accuracy rate. Another thirty-eight lots (34%) sold below, while nineteen (17%) sold above. The sale as a whole did not do as well as it could have, likely because of the twenty-three lots (21%) that went unsold. Among the works bought in were several highly-valued lots like Sir George Clausen’s Portrait of the Girl, estimated to sell for between £150K and £250K. There was also Frank Cadogan Cowper’s Fair Rosamund and Queen Eleanor, to which specialists assigned a £200K to £300K estimate range. Had these works received a bit more attention or had their reserves been slightly lower, the sale would have surpassed its £2,794,700 total minimum presale estimate. Instead, it fell just short at £2,699,500.

____________________

Deeper Thoughts

By: Nathan & Amy

Bogus Banksy Offers Critique On Street Art

The Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in Glasgow, Scotland’s largest city, opened a Banksy exhibition called Cut & Run on June 15th. This is Banksy’s first officially sanctioned exhibition in fourteen years, which makes it a momentous event given the anonymous street artist’s rise in notoriety since his last show. Around the same time as the opening, a Banksy-style work appeared on one of Glasgow’s main streets. For a brief moment, some believed that not only was Banksy active in Glasgow, but he may have been trying to drum up interest in his new show. However, those theories were quickly quashed when two local artists claimed responsibility for creating what we now know is a fake Banksy mural.

On a wall on Buchanan Street, Ciaran Glöbel and Conzo Throb created a graffiti mural featuring a rat, a common subject for Banksy. In the mural, the rat is wearing a hat with a Union Jack pattern, carrying a marching band bass drum with the phrase ‘God Save the King’ painted in red across its surface. Many Glaswegians, and Brits in general, will recognize these features as references to the Orange Order, a conservative unionist group mainly known for supporting Northern Ireland and Scotland remaining part of the United Kingdom. They are also known for their parades and other public displays where such paraphernalia are commonplace. The rat’s tail is also caught in a mouse trap, where a copy of Rupert Murdoch‘s newspaper The Sun is the bait instead of a piece of cheese. Glöbel and Throb are admirers of Banksy and claim that they studied his work extensively in preparation for executing the graffito. Though the pair of Scottish street artists did try to pass off their work as a genuine Banksy, they were quite quick to come forward once it was revealed that Banksy was not the author of the work. Glöbel even posted a video on his Instagram showing how the two created the mural.

One of Glöbel and Throb’s goals in creating the mural was to highlight an interesting double standard in the contemporary art market. Street art has been crossing over into the mainstream art market for decades, with celebrated artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat being some of the first to elevate art forms like graffiti in the eyes of collectors and gallerists. Today, artists like Bradley Theodore, Shepard Fairy, JR, and Bansky continue to influence contemporary street art and its market. However, many lesser-known artists have their work dismissed, painted over, or washed away since it is often considered vandalism rather than art. Case in point, the Glasgow City Council fell right into Glöbel and Throb’s trap. As soon as it was revealed that they were the true artists rather than Banksy, local authorities partially painted over the mural and announced plans to remove the work.

Despite its world-renowned street art scene, Glasgow spends more money than any other British city to remove graffiti from its public areas. This fact was reportedly one of the reasons Banksy chose Glasgow as the site of his new exhibition. The GOMA itself is somewhat of a symbol of subversive art. The equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington that stands out front is one of the most iconic symbols of the city. But, since the 1980s, the statue’s head has been perpetually topped with an orange traffic cone. No matter how often the cone is removed by police, another takes its place shortly thereafter. It is one of the world’s longest-running pranks and, arguably, one of the world’s most famous pieces of subversive art. Fittingly, Banksy has called the statue his “favourite work of art in the UK”. The city council has recently entertained the idea of building walls where street artists can create graffiti legally. Those who favor such a project argue that this would save the city money and bring a little color to some of Glasgow’s neighborhoods. This is a new idea, but many hope it gains traction. Projects like legal graffiti walls may allow previously anonymous artists to gain wider recognition for their work rather than face harassment by police. But on the other hand, the anonymity of some street artists like Banksy himself adds to their allure and, therefore, their notoriety. But just like how the cone atop the Duke of Wellington’s head will always be replaced, people will express themselves in whatever way they please, whether it’s on a canvas or on a wall on the street. So who knows? Should this concept get off the ground in Britain and beyond, graffiti and other street art may gain newfound respect and appreciation.

Picasso’s Guernica At 86

The 1937 World’s Fair was the International Exposition held in Paris, highlighting “art and technology in modern life”. Like in previous world fairs, many countries had their own pavilions to display the scientific, artistic, and commercial progress they had made since the last international gathering. The exposition organizers built many of these pavilions in the Trocadéro Gardens, just across the Pont d’Iena from the Eiffel Tower. Among the pavilions in these gardens were those of Austria, Denmark, Egypt, Japan, Romania, Uruguay, and many others. But the two towering structures at the gardens’ entrance after crossing the Pont d’Iena were the Nazi German and Soviet pavilions. Both were incredibly large buildings running parallel to the riverbank, with a German eagle atop one and a pair of workers holding aloft a hammer and sickle atop the other. The two structures almost seemed to have been staring each other down, which retrospectively seems appropriate given the events of the next decade. But at the time, a more evident irony may have struck some visitors. In the shadow of Germany’s swastika-clutching eagle stood the Spanish pavilion. Spain’s building was a more modest affair, built and outfitted by the Spanish Republican government one year into fighting a civil war against nationalist rebels led by General Francisco Franco. The dark irony of having the German and Spanish pavilions so close to each other was because on April 26th, nearly one month before the exposition’s opening, the Nazi air force’s Condor Legion, at Franco’s request, bombed the town of Guernica in Spain’s Basque Country and killed over sixteen hundred civilians in the process. Many historians now say that the town was not a legitimate target and that the bombing constituted a war crime. Nazi German involvement in the bombing campaigns served as practice runs for the blitzkrieg tactics seen in Poland two years later.

News of the bombing shocked the entire world and provoked many artists to create works in response. For example, the Belgian surrealist René Magritte created his painting Le drapeau noir, while the French sculptor René Iché created his bronze statue Guernica. In Iché’s case, he made the sculpture the day after the bombing and considered it so grotesque that he refused to exhibit it during his lifetime. But the one artwork most often associated with the bombing of Guernica is the groundbreaking work by Pablo Picasso, first unveiled at the Paris Exposition’s Spanish Pavilion on July 12th. Despite being one of Spain’s best-known artists, Picasso had been living in Paris for the past thirty-three years. Spain’s Republican government commissioned him to create a mural for the pavilion, namely one that would call greater attention to the ongoing civil war. Five days after the bombing, Picasso abandoned his original ideas for the work and began making sketches for what would eventually become Guernica. He completed the job in thirty-five days.

Guernica is nothing if not chaotic. It consists of human and animal figures, both alive and dead, painted in black, white, and gray. The lifeless bodies, the looks of anguish on some figures’ faces, a hand clutching a broken sword, and the dull color palette convey destruction, havoc, sadness, and everything else that war brings. Guernica received mixed reviews in Paris, with conservative critics bemoaning that the work was too modernist. Spanish republicans criticized the work as failing to take a more overt stance against fascism, while many others complained that the painting did not offer hope for the future among the wreckage and carnage. However, some interpretations of the work fly in the face of these criticisms. The bull is one of the painting’s major figures and likely represents Spain itself, since the bull is considered a sort of national animal. Because of the bull’s reputation as an aggressive animal (no doubt reinforced by Spain’s bullfighting traditions), some interpret its presence in Guernica as representing the destruction wrought by fascist forces on Basque civilians. The figure clutching the broken sword has their other hand outstretched. Picasso placed a stigma in the palm similar to the stigmata Christ received during his crucifixion, indicating martyrdom. Furthermore, two small glimmers of hope are inserted into the work: one is a flower growing right next to the shattered sword, and the other is a dove between the horse and the bull. Though cloaked in shadow, the dove is still alive.

Guernica did not gain widespread popularity until it went on an exhibition tour to drum up support for the Spanish Republican cause. It first traveled across Scandinavia, then to Britain before being sent to the United States. By the time Guernica was first exhibited in New York, General Franco had already claimed victory, and Guernica was being used to promote raising funds to aid Spanish refugees. Picasso gave the painting to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, requesting that the work be brought to Spain only when democracy had been restored. Pablo Picasso would not live to see Guernica displayed in Spain, passing away two-and-a-half years before the start of Spain’s transition to democracy that began with Francisco Franco’s death in 1975. It was only in 1981 that the painting was brought to Spain, where it remains at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid.

There are some, particularly Basque nationalists, who say that the painting should be displayed in the Basque Country rather than Madrid. The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, just thirteen miles west of Guernica, would be a particularly suitable place to put the painting on display. But regardless of where people go to see it, Guernica remains one of Picasso’s greatest works and one of the greatest anti-war artworks ever created. Upon seeing it in the Spanish Pavilion, Jean Cocteau very presciently commented that Guernica would become a cross that “Franco would always carry on his shoulder.” A large tapestry copy now hangs at the Security Council room’s entrance at the United Nations New York headquarters. Even decades after its creation, the painting’s imagery as an anti-war symbol remained so powerful that when Colin Powell went to the United Nations to justify the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the tapestry was covered up by a blue curtain so that it would not be visible while Powell fielded questions from the press. And just this past February, French artist Jean-Pierre Raynaud created his own work inspired by Picasso’s painting in response to the ongoing war in Ukraine. This shows that Guernica is just as striking and contains a message as important today as it was eighty-six years ago in 1937. As long as there is conflict, there will be people who will invoke Guernica, who will invoke the memories of those killed in Spain, as a way to advocate for those who suffer, and to stand up against those who make war.

Canada Helps Preserve Indigenous Art

In March, I wrote about how police in Canada uncovered a forgery ring that specialized in art in the style of the Canadian indigenous artist Norval Morrisseau. Some called this criminal enterprise the world’s biggest art fraud conspiracy. Indigenous art has always been a sticky subject in Canada. For decades, indigenous Canadian artists often went unpaid or unrecognized for their work, with people buying and reselling them to galleries for exponentially greater prices. The plight of indigenous artists in Canada is one of the main reasons why Canada is now considering implementing the droit de suite, the policy in effect in much of Europe where an artist or their estate would receive a payment each time their work is resold during their lifetimes and a set number of years after their deaths. Furthermore, white settlers, explorers, and traders stole many Canadian indigenous communities’ art and other cultural objects. Many indigenous artworks looted from gravesites or forcibly taken from villages are now on display in museums worldwide. Thankfully, some museums today are starting to recognize the sketchy nature of these changes in ownership, with some working with indigenous communities to have artifacts returned to them. Canada is now emphasizing their commitment to preserving indigenous heritage by funding a project that digitizes thousands of artworks.

In March, I wrote about how police in Canada uncovered a forgery ring that specialized in art in the style of the Canadian indigenous artist Norval Morrisseau. Some called this criminal enterprise the world’s biggest art fraud conspiracy. Indigenous art has always been a sticky subject in Canada. For decades, indigenous Canadian artists often went unpaid or unrecognized for their work, with people buying and reselling them to galleries for exponentially greater prices. The plight of indigenous artists in Canada is one of the main reasons why Canada is now considering implementing the droit de suite, the policy in effect in much of Europe where an artist or their estate would receive a payment each time their work is resold during their lifetimes and a set number of years after their deaths. Furthermore, white settlers, explorers, and traders stole many Canadian indigenous communities’ art and other cultural objects. Many indigenous artworks looted from gravesites or forcibly taken from villages are now on display in museums worldwide. Thankfully, some museums today are starting to recognize the sketchy nature of these changes in ownership, with some working with indigenous communities to have artifacts returned to them. Canada is now emphasizing their commitment to preserving indigenous heritage by funding a project that digitizes thousands of artworks.

About 89,000 works belonging to the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, an arts organization by and for Inuit artists in Nunavut, are now being photographed and digitized. Many of these prints and drawings have been in boxes in an Ontario archive since 1990 when the Co-operative sent the collection south to keep it safe from local wildfires. Many works are by prominent Inuit artists like Kenojuak Ashevak, Jamasie Teevee, and Pudlo Pudlat. Plans to catalogue the works have been up in the air since then, but it was never possible. Much of the collection, known as the Kinngait or the Cape Dorset collection, has been photographed before. However, camera quality has greatly improved since 1990, so the efforts started again in 2017 in collaboration with York University. After digitizing 4% of the collection, Sarah Milroy, curator for the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, where the works are being stored, sought out a way to speed everything up. She reached out to photographer Edward Burtynsky. Burtynsky sits on the board of Toronto Metropolitan University’s Image Centre and is known for large-format environmental photography. After some planning, Burtynsky’s studio developed a way to expedite the process of photographing and digitizing the enormous collection. The team created a large turntable, allowing specialists to simultaneously load works onto the rotating platform while others are photographed. The turntable requires three people to operate it and is estimated to speed up the whole process by about four or five times. The team has used the turntable since March and estimates that photography should be complete by mid-July.

Burtynsky plans to build a series of turntables, called ARKIV360 machines, to sell or rent to museums, galleries, and archival centers. The West Baffin collection should be fully digitized and available online by the autumn, with an exhibition scheduled for 2025. The project received much-needed help when Pablo Rodriguez, Minister of Canadian Heritage, announced that the digitization efforts would receive C$430,970 (or US$325,660) through the ministry’s Museums Assistance Program. Several thousand digitized works will soon be available via a new website made possible by Digital Museums Canada.

Lost Gainsborough Found In Storage

The Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) has announced that a portrait sitting in storage for over sixty years has now been attributed to the great eighteenth-century British portraitist Thomas Gainsborough. The painting is an unsigned portrait of a one-armed man in a naval uniform. It was bequeathed to the National Maritime Museum in 1960 as a portrait by Gainsborough. However, curators were skeptical of this attribution at the time, saying it was “too coarse” to be a true Gainsborough.

The Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) has announced that a portrait sitting in storage for over sixty years has now been attributed to the great eighteenth-century British portraitist Thomas Gainsborough. The painting is an unsigned portrait of a one-armed man in a naval uniform. It was bequeathed to the National Maritime Museum in 1960 as a portrait by Gainsborough. However, curators were skeptical of this attribution at the time, saying it was “too coarse” to be a true Gainsborough.

However, last year, Gainsborough expert Hugh Belsey asked to examine the work. He was researching the provenance of a lost masterwork, Portrait of Captain Frederick Cornewall, and could not find out where the painting went after 1960. By a stroke of luck, Belsey saw the work’s image in a catalogue of the National Maritime Museum’s collection, not as a Gainsborough but attributed to an unknown artist. He requested to see the work, and shortly thereafter positively identified it as an original Gainsborough, created around 1762 when the painter worked in Bath. Cornewall was a British naval officer who, when he had his portrait painted by Gainsborough, had just recently retired. His jacket’s empty right sleeve is pinned to a button on his waistcoat, a fashion some might be familiar with through much later depictions of Horatio Nelson. Cornewall had lost his arm in 1744 at the Battle of Toulon during the War of Austrian Succession.

The portrait is in good condition but “very fragile”. The varnish applied to the canvas, which has since yellowed with age, must be removed to show the portrait’s true colors. This is a delicate process that is complicated by the possibility of paint flaking off the canvas. The RMG, which now operates the National Maritime Museum, is trying to raise £60,000 towards its restoration to be exhibited at Queen’s House. The portrait is now only one of two paintings by Gainsborough in the RMG collections, the other being his Portrait of John Montagu, Earl of Sandwich.

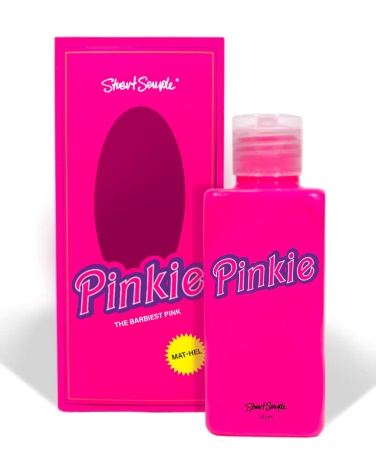

Semple-Y Pink

In recent years, people have tested the limits of what you can and cannot copyright. Ten years ago, the US Supreme Court ruled against the company Myriad Genetics after trying to get patents for naturally occurring DNA sequences. Parker Brothers currently owns the copyright to the terms Ouija Board and Ping-Pong. So if you’re not getting them from Parker Brothers, you’re just getting a generic spirit board or a packet of table tennis balls. This obsession with copyright and trademark also applies to different colors. Plenty of private entities technically own or have exclusive rights to various colors, including Tiffany Blue, T-Mobile Magenta, Pullman Brown (trademarked by UPS), and Canary Yellow (trademarked by 3M, the maker of Post-It notes). Anyone who uses these colors without express permission from the trademark holders may be at the receiving end of a lawsuit if things go that far. Typically, this only happens when a company in the same industry uses that color. For example, Hershey’s has monopolized the use of orange in the candy packaging and marketing since that color is often associated with Reese’s. One color that might be more visible currently, mainly because of Greta Gerwig’s new movie, is Barbie Pink, which Mattel trademarks. However, artist Stuart Semple does not believe that anyone or any company has the right to own colors, and he expresses this in a way that is hilarious and just a little bit petty.

Semple has created his own colors before and has just come out with a new one called Pinkie, which he calls the “Barbiest pink”. But while Mattel prohibits anyone from using their Barbie Pink, Semple has made Pinkie available to everyone except for Mattel. When you purchase an order of Pinkie paint, you must sign forms swearing that you are not an employee of or associated with Mattel. This is not the first time that Semple has done this. In 2016, British artist Anish Kapoor bought the rights to a new color, Vantablack. It is considered the blackest black paint in the world, absorbing 99.96% of the light that touches it. Kapoor caused quite a stir when he did this, with many artists saying that no individual should have exclusive rights to a color. In response, Semple announced he had developed some new colors, including Pinkest Pink, Yellowest Yellow, Greenest Green, and Loveliest Blue. Eventually, he would develop Black 3.0 and Blink, his proprietary brands of black acrylic paint and black ink, which he marketed as the darkest shades of black available, or, in his words, they are “Stupidly Black”. Regarding all these new colors, Semple made them available for purchase along with forms requiring anyone who buys the colors to swear that they are not Anish Kapoor, nor are they affiliated with or buying on behalf of Anish Kapoor. Semple has even taken a shot at Tiffany’s, creating his own shade of Robin’s egg blue that he called Tiff.

Similar to Tiff, which comes in a box nearly identical to the ones used by Tiffany’s, Pinkie comes in bright pink packaging with a clear plastic front, evoking the design Mattel uses to sell Barbie dolls. According to Semple and his company Culture Hustle, these paints do not constitute theft or copyright infringement, but rather these colors being “liberated”. Pinkie is not exactly a match to Barbie Pink, but that was intentional. Semple claims he set out to make an “even better” shade of pink. “It is SO pink that it’s even pinker than the Pinkest Pink. And I did that to show that everyone can have a color that is way better than theirs.” Starting on July 28th, 5 oz. bottles of Pinkie will become available for purchase at $34.99.

Tubes: The Invention That Made Art Modern

Many of the great milestones in art history involve famous artworks. For example, at the time of its creation, Donatello’s statue of David was the first male nude sculpture created since antiquity and is now one of the great works of the Early Renaissance. When Emperor Napoleon had Anne-Louis Girodet’s 1802 painting Ossian Receiving the Ghosts of French Heroes hung at his chateau, it is considered by some as one of the first times Romantic painting entered the mainstream. And Picasso’s landscapes from 1909, among them Reservoir at Horta de Ebro, are often considered the start of Cubism. But there are few recorded moments when the arts were changed forever because of innovation in the artistic media itself.

On September 11, 1841, an American painter named John Rand submitted his patent for the collapsible paint tube. By the mid-nineteenth century, most painters did not mix their own paints, instead getting their colors from vendors. However, the containers used before Rand’s invention were rather primitive. The most portable way to store paint was a pig’s bladder tied with string. You would choose a few colors, then pierce each bladder with a pin or a tack to get the paint out. With no way to plug the hole, you had to use all the paint right then and there. Furthermore, these pig’s bladders were often difficult to transport, limiting painters’ ability to work with as diverse a color palette as they wished if they wanted to travel to a specific location. Another option available in the early nineteenth century was a sort of glass syringe, which allowed artists to push out as much as they needed at the time. This is more or less how French landscape painters worked, like those of the Barbizon school. Since they could only take a few colors with them at a time, a single landscape painting often took dozens of sittings to complete, with each session only focusing on a small part of the canvas. While living in London, John Rand came up with a solution: to take the syringe idea, but make it into a tube made from thin, flexible pieces of tin. Instead of pushing paint out with a plunger, a painter could squeeze it, and then seal it up (the screw cap wouldn’t come along until 1859). This kept the oil paints fresh longer than any porcine innards could. Because of this, as well as being more portable, artists could now bring their entire stock of paints when they went out to paint outside.

Because tin was rather expensive at the time of Rand’s invention, it took time for the tubes to catch on among artists. But everyone eventually came around to the idea. Jean Renoir, son of the great Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir, claims that his father once said that without Rand’s tubes, “there would have been no Cézanne, no Monet, no Sisley or Pissarro, nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionism.” Of course, there is more to Impressionism than painting en plein air. However, it would be foolish to disregard the impact of portable paint tubes on artists’ ability to go out into nature and capture a given location in one or two sittings. Now that they didn’t have to run back home to fetch their pig bladder of chrome yellow if they had to, the Impressionists could produce landscapes at a rapid pace. This also led to the distinctive Impressionist style of using short, quick brushstrokes and introducing abstraction to the work’s subject. Furthermore, the paint sold in these tubes was often rather thick. To work with it, many painters resorted to working with sturdier brushes, resulting in some painters like Vincent van Gogh using thick impasto on their canvases.

Because tin was rather expensive at the time of Rand’s invention, it took time for the tubes to catch on among artists. But everyone eventually came around to the idea. Jean Renoir, son of the great Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir, claims that his father once said that without Rand’s tubes, “there would have been no Cézanne, no Monet, no Sisley or Pissarro, nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionism.” Of course, there is more to Impressionism than painting en plein air. However, it would be foolish to disregard the impact of portable paint tubes on artists’ ability to go out into nature and capture a given location in one or two sittings. Now that they didn’t have to run back home to fetch their pig bladder of chrome yellow if they had to, the Impressionists could produce landscapes at a rapid pace. This also led to the distinctive Impressionist style of using short, quick brushstrokes and introducing abstraction to the work’s subject. Furthermore, the paint sold in these tubes was often rather thick. To work with it, many painters resorted to working with sturdier brushes, resulting in some painters like Vincent van Gogh using thick impasto on their canvases.

The creator of the collapsible paint tube would not live to see his invention’s potential fully realized. John Rand would pass away in 1873, only a year before Claude Monet debuted his Impression, soleil levant at the Impressionist Exhibition. Rand’s invention was such an innovative breakthrough that, even today, some actively try to erase Rand’s memory. The British paint manufacturer Winsor & Newton openly state on their website that they were the ones who developed the collapsible tubes. Of course, William Winsor did try to develop his own tin tubes for paint, but Rand’s design was far superior since Winsor’s tubes were prone to leaking and breaking.

Is AI Art Copyright Infringement?

Artificial intelligence in the art world is getting more and more attention. Mainly, I’ve written about AI being used in the study of art, like people using various programs to determine a painting’s authenticity or attributing a work to a specific artist. But I haven’t really touched upon AI-generated art. This topic became more of a talking point after German artist Boris Eldagsen turned down a photography prize he had won after revealing that the winning picture was AI-generated. Incidents like these have provided food for thought for many on all sides of the debate. When is using AI fair game? And where is the line between using it responsibly and cheating? But a group of artists is asking a new question: to what extent are AI-generated images copyright infringement?

Artificial intelligence in the art world is getting more and more attention. Mainly, I’ve written about AI being used in the study of art, like people using various programs to determine a painting’s authenticity or attributing a work to a specific artist. But I haven’t really touched upon AI-generated art. This topic became more of a talking point after German artist Boris Eldagsen turned down a photography prize he had won after revealing that the winning picture was AI-generated. Incidents like these have provided food for thought for many on all sides of the debate. When is using AI fair game? And where is the line between using it responsibly and cheating? But a group of artists is asking a new question: to what extent are AI-generated images copyright infringement?

Artists Sarah Andersen, Karla Ortiz, and Kelly McKernan are the plaintiffs in a lawsuit now being heard in district court in California. The artists allege that companies like Stability AI, Midjourney, and DeviantArt used their work to train their text-to-image generators. Therefore, any images these AIs produce are derivative works and a violation of copyright. However, the defendants have highlighted that, of the plaintiffs, only Andersen has works registered with the US Copyright Office. But even if all the artists held valid copyright for their creations, these companies claim that there needs to be a direct comparison between works to allege copyright infringement. Because the companies trained the AIs using dozens of these artists' works, the images the AIs produce are not copies of individual pieces but are influenced by the artists’ specific styles. There is a difference between stealing from a particular work and creating something new but in another artist's style. Furthermore, the AIs these companies developed did not just use these three artists’ works. The programmers used thousands of works from thousands of artists to train their respective AIs. If these AIs are trained properly, it would be nearly impossible to pinpoint any generated image or any part of an image as directly copied from another work.

Senior Judge William Orrick III heard oral arguments and, based on his questions and commentary, seemed skeptical of the artists’ arguments. Some claim that should Orrick decide against the artists, it is evidence that US copyright law as it currently exists is not adequately equipped to tackle issues concerning AI-generated art. The artists will also have the chance to appeal if they so choose.

Old School, New School: Edward Kaprov's Photos From Ukraine

There are lots of good photojournalists working today. In particular, war photographers have a more difficult job than most, going into active war zones to cover how the conflict is progressing and how the lives of those caught in the middle have changed. And today, there are few places to get work as a war photographer quite like Ukraine. However, Soviet-born Israeli photographer Edward Kaprov stands out for using old techniques on modern subjects. Kaprov uses one of the oldest forms of photography, the wet plate collodion method. It involves taking collodion, or nitrocellulose dissolved into alcohol and ether, and pouring it over aluminum or glass plates. Those plates get dipped into silver nitrate, creating a photosensitive surface. The photographer exposes the plate to the light while still wet, then treats it with water and several other chemicals, creating a black-and-white impression known as tintypes when on aluminum or ambrotypes when on glass. Because you must take the photo while the plates are still wet, this process must happen very quickly. For photographers who want to work outdoors, this requires them to build portable darkrooms. Kaprov has been drawn to borderlands for much of his career. His work has taken him from Israel to Chechnya and now Ukraine.

This is not the first time wet plate collodion photography has been used to document a conflict in Ukraine. In 1854, the British photographer Roger Fenton became one of the first noteworthy war photographers when his battlefield pictures of the Crimean War circulated among British newspapers. Fenton converted a horse-drawn wagon into a studio to develop his pictures in the field, resulting in works like The Valley of the Shadow of Death taken in the aftermath of the Siege of Sevastopol. Following in Fenton’s footsteps, Kaprov has his mobile darkroom, using a converted Ford Transit instead of a wagon. Not long after Russian troops crossed the border into Ukraine, Kaprov loaded it up with about a hundred glass plates and over six hundred fifty pounds of chemicals and water. While a good deal of contemporary war photography tries to catch combatants in the moment of action, Kaprov’s preferred medium does not allow that. His subjects must stand completely still while the plate captures the image. These photos' color and quality make it look like they were taken on the First World War’s Eastern Front. His landscape pictures of felled birch trees have the same aura as those taken in the Argonne Forest in 1915. A viewer could easily mistake the still moments of soldiers for shots taken during the Russian Civil War if it weren’t for the modern firearms. Kaprov noted that it is the signs of modern life combined with the older medium that he wishes to make viewers look twice. “I want to confuse the audience, […] I want the act of comparing them with past wars, because in fact nothing has changed. Maybe the weapons and cellphones have changed, but the essence of war does not change.” By using the same method in the same place as Fenton, Kaprov to some extent consciously repeats this cycle.

Because of the relatively lengthy process of setting up the box camera, taking a photograph, then rushing back to the van to have it developed, there’s an intimacy to Kaprov’s photographs that not many photojournalists in Ukraine have been able to capture. It’s not simply the intimacy between the subject and the viewer but between the subject and the artist. In documentary footage, Kaprov often converses with his subjects and gets to know them, asking about their experience before and during the war. Kaprov also uses his van to transport supplies and people if needed. He said to ARTE.tv, “I don’t think photography can end the war. It gives me an excuse to stay close to these people and do everything to help them, with pain and compassion.” The photographs are therefore more personal, especially with the context. But with Kaprov, there is also a personal connection. Though he was born and raised in the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, less than 90 miles from the border with Kazakhstan, Kaprov’s grandparents were all from Ukraine. All four were from Zhytomyr, a city 90 miles west of Kyiv that sustained some damage from Russian airstrikes in the early days of the invasion in March 2022.

Anyone who studies the past can tell you that history is seldom linear, but it is often cyclical. Kaprov's message can be interpreted as a depressing reminder that war and conflict will continue to plague us even if everything else changes. But the perceived anachronism between the medium and Kaprov's subjects is so striking that it breathes new life into issues that many have grown weary of hearing about.

The Rehs Family

© Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York – August 2023