COMMENTS ON THE ART MARKET

Gallery News

May Gallery Exhibition

Rehs Contemporary, in partnership with Art Renewal Center, is pleased to announce their upcoming exhibit, INSIGHT. Opening to the public on May 26, 2022, INSIGHT features artwork by 5 international artists of various nationalities – Jesús Inglés and Arantza Sestayo (Spanish), Alexandra Klimas (Dutch), Roman Pankov (Ukrainian), and Anne-Marie Zanetti (Australian).

____________________

Stocks & Crypto

By: Lance

As many expected, April was not a good month for the stock market… the first few weeks saw choppy trading, but generally trending downward. Then things fell off a cliff on the 21st… I guess the high wore off. With just a handful of positive days, April ended up being the worst month in years. The Dow was actually positive until the final week, up more than 2% before dropping precipitously to close out down 5%; a 2,500 point swing in a matter of days. The rout was on for the NASDAQ, down more than 13% for the month! The S&P landed between the two – finishing the month with a nearly 9% loss. Again, it was not a surprise with bad news swirling, but likely still a bit of a shock to many.

Turning to currencies and commodities… relative to the dollar, the Euro was down more than 2% while the Pound was down nearly 1%. Another notable movement was the yen – with Japan’s announcement that they will keep interest rates near 0%, the yen has tumbled to a 20-year low; currently .0077, down more than 10% since early March. Gold pulled back from the $2,000 level it had been flirting with… just days before the stock market took a downturn, gold reversed course and fell below $1,900. Crude seems to have somewhat stabilized in the $95-105 range, granted that still allows for some significant movement week-to-week… it finished off the month just inside that range, currently at $104.51. That said, there was significant news regarding Russian oil… in the final days of the month, Germany dropped its opposition to an embargo. Prior to that, Germany signaled they would give way to demands that payment be made in rubles; conversely, Poland and Bulgaria refused and saw their supply cut off. A more united European front is certainly necessary if we expect economic sanctions to be effective.

Looking at crypto, we had more numbers in the red… Bitcoin fell below $40K again, now sitting just below $39K, representing a loss greater than 18% for the month. Ethereum fared slightly better, down about 16% and currently around $2,800. Litecoin was hit the hardest, falling below $100 with a loss of more than 21%!

Wish I could leave you on a better note, but I got nothing. A recent investor sentiment survey indicated nearly 60% of responders were bearish, the highest it has been since 2009 following the financial crisis. Maybe it’s time to buy some art instead of stocks, hey, just an idea.

____________________

The Dark Side

By: Nathan

The Warhol Supreme Court Faceoff

Andy Warhol is known for many things, soup cans and flowers among them. But his portraits are often cited as some of the pop art icon’s most recognizable works. From Marilyn Monroe to Mao Zedong to Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol seems to have immortalized every great cultural figure of the twentieth century in neon-colored silkscreen. Among Warhol’s portrait subjects, the musician and 1980s icon Prince is just one of many. But it’s a Warhol portrait of Prince that’s the subject of an upcoming US Supreme Court case.

Andy Warhol is known for many things, soup cans and flowers among them. But his portraits are often cited as some of the pop art icon’s most recognizable works. From Marilyn Monroe to Mao Zedong to Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol seems to have immortalized every great cultural figure of the twentieth century in neon-colored silkscreen. Among Warhol’s portrait subjects, the musician and 1980s icon Prince is just one of many. But it’s a Warhol portrait of Prince that’s the subject of an upcoming US Supreme Court case.

It all started in 2016 following Prince’s death, when Vanity Fair published an article on the late musician. Accompanying the article was a number of colorful portraits of Prince done by Andy Warhol in the years leading up to the artist’s 1987 death. That’s when Lynn Goldsmith noticed something out of place. Warhol’s portraits bore a striking resemblance to a photo she had taken of Prince in 1981. Lynn Goldsmith is a musician and a photographer known for having taken photos of many celebrities and public figures. While she may occasionally snap a picture of Hillary Clinton or the Dalai Lama, she’s always been a musical photographer at heart. Singers and musicians are her most common subjects, including Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Michael Jackson, and Bruce Springsteen. She’s also taken pictures for a number of recognizable album covers, most iconically Frank Zappa’s Sheik Yerbouti. But the center of this legal battle has to do with Goldsmith’s 1981 black-and-white portrait of Prince.

Goldsmith originally licensed the photo to Vanity Fair in 1984 for use in an article about Prince entitled “Purple Fame”. The magazine then reached out to Warhol to create a portrait based on Goldsmith’s photograph. The Warhol portrait accompanied the article, but Vanity Fair credited Goldsmith for the original work. However, Warhol went on to create an additional fifteen portraits of Prince based on the original photograph without Goldsmith’s permission. After discovering this, Goldsmith reached out to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF), the organization that holds the copyright to all Warhol works. It seems her efforts to remedy the situation failed, because she then registered the original photo with the US Copyright Office. The AWF sued, while Goldsmith countersued, starting the legal battle that has continued to the present day.

In New York federal court, Judge John Koeltl ruled that although photographs are copyrightable, “the subject itself – and general features of that subject – are not.” Furthermore, Judge Koeltl wrote that Goldsmith doesn’t really have a case against the AWF because of Warhol’s transformation of the original photograph. The changes that Warhol made “result[ed] in an aesthetic and character different from the original. The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.” This decision, however, was overturned on appeal. The panel of appellate judges ruled that a secondary work being transformative cannot be determined just by the artist’s intent or the perceptions of the work. “[W]hether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic – or for that matter, a judge – draws from the work. Were it otherwise, the law may well ‘recogniz[e] any alteration as transformative.’” Faced with this new ruling, the AWF has appealed to the Supreme Court, who agreed to hear the case this past Monday.

A group of professors of both copyright and art law, as well as lawyers representing the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, and the Brooklyn Museum, have already submitted briefs to the Supreme Court supporting the AWF’s case against Goldsmith. While the AWF wants to portray the situation as artistic free expression under siege by some random photographer and the US legal system, what this case really deals with is simple: fair use within the context of copyright. These cases are context-based, and even if the justices side with Goldsmith, by no means will it create a new case law precedent for future free use copyright disputes. In law, there are certain circumstances where the free use justification is applicable, like commentary or journalism. No author is going to sue a literary critic because they used a quote from one of their books in a review. But taking someone else’s photograph, making an exact copy via screenprint, and then just changing the color is, by most people’s definition, not a wholly original work and is a clear and blatant infringement of copyright. The AWF is just making a fuss over a mistake their namesake made, and now they don’t want to look bad in front of everyone.

Shame on Shein

The online fast-fashion retailer Shein (pronounced like sheen rather than shine, like I mistakenly did the first few times) is known globally for being one of the best in connecting shoppers to affordable products. Millions of people, especially the younger generations, love Shein. People online use the tag #SheinHaul when making unpacking videos for their latest order, sometimes containing dozens of items. But for such a massive, successful company, Shein seems to fall short when creating designs for their products, which has led them to use the works of other artists without their express permission.

Vanessa Bowman is the most recent artist to voice their concerns over this practice. She is a British painter who mainly creates still lifes and landscapes inspired by her native Dorset on the southern English coast. Her works are absolutely charming, with a simplicity and a command of color that seems inspired by the well-known folk and naïve painters like Henri Rousseau or Grandma Moses. Her work is seen by thousands not only on her popular Instagram page, but in the pages of House & Garden magazine, on holiday cards sold by Prince Charles’s Highgrove Estate, and on the walls of London’s Bridgeman Library. Not long ago, she received an email from a fan in Canada letting her know that a sweater featuring an image of one of her works was available on Shein for £17. According to Bowman, Shein never reached out to her for permission, and it appears they made no effort to cover up their theft since they just copied and pasted Bowman’s unedited image onto their clothing. And Bowman is far from the only artist who has experienced this.

Many more artists have launched similar accusations at Shein. Another British artist, Elora Pautrat, first realized Shein was stealing her work in 2020. After the company apologized and gave her a settlement, they proceeded to steal her work an additional ten times to create stickers and posters. It seems that the Shein employees are completely unresponsive when artists contact them through the appropriate channels, with no action taken to remedy the situation until the company is called out publicly on social media. But at least Shein doesn’t discriminate, as they steal from independent artists as well as large corporations. Dr. Martens sued Shein last year for trademark infringement, while the company already settled with Levi Strauss for an undisclosed amount in 2018.

The Artists’ Union, which represents hundreds of British artists, has called for Shein to be “exposed, challenged and named and shamed”. But honestly, copyright infringement is not the only thing for which Shein needs to be shamed. Despite being incredibly popular with Generation Z, which tends to be more concerned with sustainability and transparency, Shein’s labor and environmental violations are well-documented. Factory workers producing Shein products typically work 75-hour weeks in brutal conditions. Their incredibly low prices result from their products being made from cheap materials, meaning they suffer wear and get thrown away at a greater rate. Their violations of intellectual property rights are only one of a string of problems with the company. The fact that they’ve been caught in the act time and time again is absolutely ridiculous. Hopefully, the Artists’ Union involving themselves will lead to effective change so Shein’s cycle of theft can be stopped permanently.

____________________

Really?

By: Amy

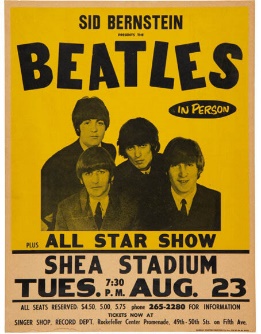

Beatles Set A New Record

The Beatles are considered the most influential and best-selling music group of all time. The iconic group first performed under the name The Beatles in 1960, and is responsible for biggest hits of the decade. They continue to hold the record as the best-selling artists worldwide, beating out Elvis Presley, Elton John, and Michael Jackson.

The Beatles are considered the most influential and best-selling music group of all time. The iconic group first performed under the name The Beatles in 1960, and is responsible for biggest hits of the decade. They continue to hold the record as the best-selling artists worldwide, beating out Elvis Presley, Elton John, and Michael Jackson.

In addition to being the best-selling band, they hold the record for sales in the United States, with 20 songs hitting number 1 on the charts. The group has a new record now: the most expensive concert poster sold at auction. The poster is from the Beatles’ August 23, 1966 concert at Shea Stadium, one of the last live concerts they performed while still touring. Six days later, the Beatles played their last concert for a paying audience at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, retiring from live shows and focusing exclusively on recording in the studio.

According to the auction room, “Unlike previous Beatles-at-Shea posters, this one of the Fab Four’s final tours was untouched by conservation experts. Its previous owner, who owned it for decades, took great care of the keepsake.” Curiously, the concert did not sell out; about 11,000 of 55,600 tickets were still available at showtime. The Beatles made $189K for their appearance, 65% of the $292K gross ticket sales. The poster came close to that total take. Bidding opened at $115K and quickly escalated, hammering down at $220K ($275K w/p), setting a record for the most expensive concert post sold at auction.

____________________

The Art Market

By: Nathan

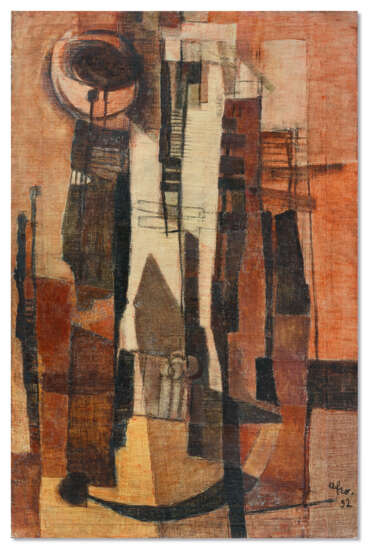

Christie’s Amsterdam 20th/21st Century Sale

This past Tuesday, April 26th, Christie’s hosted a post-war and contemporary art sale at their seldom-used Amsterdam saleroom. While watching the sale, it was fascinating to see interest fluctuate so greatly from lot to lot. Either a work sold dramatically over its estimate, or disappointingly fell short of its estimate. It certainly kept me on my toes while watching. The top lot, for example, was Paesaggio rosso, or Red Landscape, an oil and chalk on canvas work from 1952 by the post-war Italian Afro Basaldella. Christie’s originally estimated it to sell for €40K to €60K, which is not too bad for a decently-sized abstract work. It eventually sold for €240K / $255.6K (or €302.4K / $322.1K w/p), four times its high estimate. It only became the top lot because the work most highly valued by Christie’s specialists, a Georg Baselitz oil painting entitled Hundekopf, went unsold. It was estimated to go for anywhere between €300K and €500K, and certainly would have surpassed everything else if more interest had been shown for it.

The other top lots at the sale fell within their estimates: Karel Appel’s 1958 oil on canvas work Têtes Volantes hit its high estimate when it sold for €180K / $191.7K (or €226.8K / $241.6K w/p). Meanwhile, the Danish painter Per Kirkeby appeared with his works entitled Dameforløb. Model Dorte: a 48-by-80-inch piece of masonite with silver paint, acrylic, enamel, graphite, ink, and metal. It also fell within its original pre-sale estimate of €100K to €150K, with the hammer coming down at €140K / €149.1K (or €176.4K / $187.9K w/p).

The other top lots at the sale fell within their estimates: Karel Appel’s 1958 oil on canvas work Têtes Volantes hit its high estimate when it sold for €180K / $191.7K (or €226.8K / $241.6K w/p). Meanwhile, the Danish painter Per Kirkeby appeared with his works entitled Dameforløb. Model Dorte: a 48-by-80-inch piece of masonite with silver paint, acrylic, enamel, graphite, ink, and metal. It also fell within its original pre-sale estimate of €100K to €150K, with the hammer coming down at €140K / €149.1K (or €176.4K / $187.9K w/p).

Though Baselitz failed to get the top lot like Christie’s specialists expected, another of his works, a linoleum and asphalt on paper piece called Flasche, surprised buyers when it sold for €15K / $15.98K (or €18.9K / $20.1K). It was originally estimated to go for anywhere between €1.5K and €2K. Similarly, the American abstract painter Kyle Morris had his name on some people’s minds because of his 1959 oil painting Thrust. It sold for €42K / $44.7K (or €52.9K / $56.4K w/p), seven times its €6K high estimate.

Though Baselitz failed to get the top lot like Christie’s specialists expected, another of his works, a linoleum and asphalt on paper piece called Flasche, surprised buyers when it sold for €15K / $15.98K (or €18.9K / $20.1K). It was originally estimated to go for anywhere between €1.5K and €2K. Similarly, the American abstract painter Kyle Morris had his name on some people’s minds because of his 1959 oil painting Thrust. It sold for €42K / $44.7K (or €52.9K / $56.4K w/p), seven times its €6K high estimate.

Overall, it was a well-balanced sale. Out of one hundred twenty-three available lots, thirty-eight fell within their estimates, while thirty-six fell short and thirty-four exceeded them. Fifteen lots, including the Baselitz work as the highest-valued lot, went unsold. The entire sale fell within the pre-sale estimate between €1.99M and €2.98M, reaching €2.24M (or $2.38M).

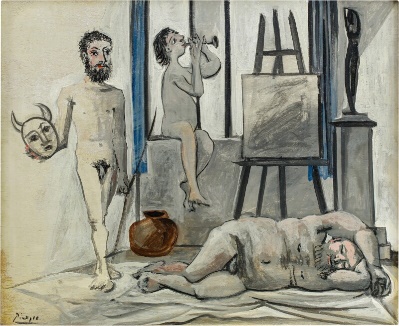

Sotheby's Paris Art Impressionniste et Moderne

Last Thursday, April 21st, Sotheby’s held their Impressionist and Modern art sale at their showroom in Paris, with some more than satisfactory results. Sotheby’s specialists were very good at predicting the top lots, with Pablo Picasso’s Nus masculins (Les trois âges de l’homme) taking the top spot in terms of both the pre-sale estimates and the hammer prices. A moderately-sized oil on canvas work from 1942, it shows three nude male figures meant to represent, as the title suggests, the three ages of a man: an adolescent playing some sort of flute, a bearded young man with a horned mask, and a heavyset older man laying on the floor. Specialists estimated it would sell for €2.5M to €3.2M, selling just beyond at €3.4M / $3.68M (or €4.14M / $4.48M w/p).

The specialists were similarly accurate about some of the other top lots. Francis Picabia’s painting entitled Tarin was also highly-valued, being a brilliant arrangement of human outlines among a group of siskin birds on leafy branches. The work is very typical of Picabia’s work in the late 1920s. Having previously experimented with cubism and Dada, Picabia was moving into surrealism during this time, marked by the figure outlines over top of simple still-lifes or portraits. Tarin was estimated to sell for anywhere between €1.9M and €2.4M, selling on the higher end at €2.35M / $2.55M (or €2.88M / $3.12M w/p).

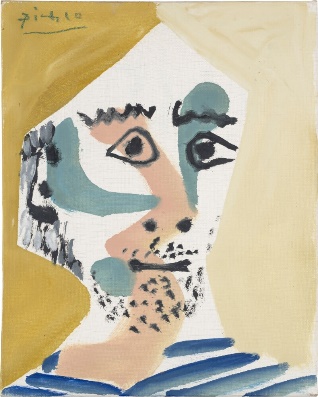

Sotheby’s experts originally expected Marc Chagall’s 1974 oil-and-ink work Le Clown multicolore to reach third place, giving it a €1.6M to €2M estimate. While it did reach €1.35M / $1.46M (or €1.6685M / $1.8M w/p), it was surpassed by €50K by one of the other Picasso works on sale. Tête D’Homme, a small portrait from 1965, hit its low estimate when it sold for €1.4M / $1.52M (or €1.73M / $1.87M w/p). The 1939 still-life Vase de fleurs au coquelicot, the third and final Picasso work at the sale, surprised everyone when the hammer came down at €820K / $885.6K (or €1.03M / $1.11 w/p), coming close to tripling the €300K high estimate. Speaking of surprises, the sale featured a string of Bernard Buffet works. Nearly all ten Buffet works either hit their estimates or exceeded them, with only one remaining unsold. One of them, an example from Buffet’s ink-on-paper series Le Bestiaire, caught my attention. A drawing of a gnarly-looking bulldog with dark eyes that was only estimated to sell for €20K maximum, sold for €55K / $59.3K (or €69.3K / $74.8K w/p). It only confirms my original hypothesis that I made following Bonhams’ 19th Century sale earlier this month: “similar to the Internet, if something has a couple of cute dogs, it’s bound to get more attention than expected.”

Sotheby’s experts originally expected Marc Chagall’s 1974 oil-and-ink work Le Clown multicolore to reach third place, giving it a €1.6M to €2M estimate. While it did reach €1.35M / $1.46M (or €1.6685M / $1.8M w/p), it was surpassed by €50K by one of the other Picasso works on sale. Tête D’Homme, a small portrait from 1965, hit its low estimate when it sold for €1.4M / $1.52M (or €1.73M / $1.87M w/p). The 1939 still-life Vase de fleurs au coquelicot, the third and final Picasso work at the sale, surprised everyone when the hammer came down at €820K / $885.6K (or €1.03M / $1.11 w/p), coming close to tripling the €300K high estimate. Speaking of surprises, the sale featured a string of Bernard Buffet works. Nearly all ten Buffet works either hit their estimates or exceeded them, with only one remaining unsold. One of them, an example from Buffet’s ink-on-paper series Le Bestiaire, caught my attention. A drawing of a gnarly-looking bulldog with dark eyes that was only estimated to sell for €20K maximum, sold for €55K / $59.3K (or €69.3K / $74.8K w/p). It only confirms my original hypothesis that I made following Bonhams’ 19th Century sale earlier this month: “similar to the Internet, if something has a couple of cute dogs, it’s bound to get more attention than expected.”

It was a very good day for Sotheby’s as 41% of the available lots sold above estimate, while only four lots (12%) went unsold. In the end, the total auction hammer price reached €15.34M, falling nicely within the original €12.79M to €17.23M presale estimate.

Christie’s Paris Jacqueline Matisse Monnier Collection

Although Christie’s hosted a rather disappointing online nineteenth-century art sale on the 12th, the next day, Christie’s Paris more than made up for it with the auction of a prominent private collection. The collection was that of the late Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, who passed away last year, the granddaughter of the French modernist artist Henri Matisse. The seventy-eight-piece collection includes works given to her directly by her grandfather, but she also inherited many of them through her father. Henri Matisse’s youngest son Pierre operated as a prominent art dealer in New York who also owned his own gallery, exhibiting and representing some of the twentieth century’s greatest artists, including those whose works were featured in the sale like Jean Dubuffet, Joan Miró, and Alberto Giacometti. But by far, her grandfather was the undisputed star of the auction, with twenty-nine lots featuring works by Matisse, including the top two lots in the auction.

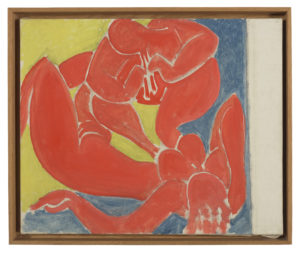

Nymphe et faune rouge, executed in 1939 using oil and crayon on canvas, is a dynamic study in primary colors. The bold red shapes reveal the curves of the lounging nymph and the satyr hunching over her playing a pair of aulos flutes. While estimated to go for anywhere between €1.8M and €2.2M, Nymphe et faune rouge nearly doubled the specialists’ expectations when it sold for €4.3M / $4.68M (or €5.19M or $5.64M w/p). Matisse got second place a few moments later with his nearly 5-by-12-foot screenprint entitled Océanie, le ciel. Despite the work’s size, it was valued at €1.2M to €1.8M, less than the much smaller Nymphe et faune rouge. It eventually reached €3.3M / $3.59M (or €4M / $4.36M w/p). It’s a companion piece to the similarly-sized work Océanie, la mer, also featured in the auction and sold for €1.7M / $1.83M (or €2.08M / $2.25M). The sculpture Petit buste d’homme by Alberto Giacometti took third place despite specialists’ expectations. The bust is typical of Giacometti’s work, with its spindly neck, elongated head, and roughly-textured, almost crude exterior. Despite it being the highest-valued lot in the sale at €3M to €5M, the Giacometti fell just short of the minimum when it sold for €2.5M / $2.72M (or €3.04M or $3.31M w/p).

Nymphe et faune rouge, executed in 1939 using oil and crayon on canvas, is a dynamic study in primary colors. The bold red shapes reveal the curves of the lounging nymph and the satyr hunching over her playing a pair of aulos flutes. While estimated to go for anywhere between €1.8M and €2.2M, Nymphe et faune rouge nearly doubled the specialists’ expectations when it sold for €4.3M / $4.68M (or €5.19M or $5.64M w/p). Matisse got second place a few moments later with his nearly 5-by-12-foot screenprint entitled Océanie, le ciel. Despite the work’s size, it was valued at €1.2M to €1.8M, less than the much smaller Nymphe et faune rouge. It eventually reached €3.3M / $3.59M (or €4M / $4.36M w/p). It’s a companion piece to the similarly-sized work Océanie, la mer, also featured in the auction and sold for €1.7M / $1.83M (or €2.08M / $2.25M). The sculpture Petit buste d’homme by Alberto Giacometti took third place despite specialists’ expectations. The bust is typical of Giacometti’s work, with its spindly neck, elongated head, and roughly-textured, almost crude exterior. Despite it being the highest-valued lot in the sale at €3M to €5M, the Giacometti fell just short of the minimum when it sold for €2.5M / $2.72M (or €3.04M or $3.31M w/p).

59% of the featured lots sold above their estimates, some going for exponentially higher hammer prices. The biggest surprise at this sale was P.M.12, a 1960 elliptical oil-on-canvas work by the French Canadian automatist painter Jean Paul Riopelle. The whole point of the Quebec automatist movement was to prevent the conscious mind from having any creative control, letting instinct and the unconscious mind dominate creation. The result is the dynamic, spontaneous, unpolished, and impasto-rich work similar to the abstract expressionism of Jackson Pollock and Riopelle’s partner Joan Mitchell. While only predicted to sell for €50K to €70K, P.M.12 kept receiving bid after bid after bid until it hit close to six-and-a-half times the high estimate, with the gavel coming down at €450K / $489.7K (or €567K or $617K w/p). Similarly, Joan Miró’s bronze entitled Femme was only estimated to sell between €80K and €120K. So it came as a surprise when it went for three-and-a-half times that at €420K / $457K (or €529.2K / €575.9K w/p).

59% of the featured lots sold above their estimates, some going for exponentially higher hammer prices. The biggest surprise at this sale was P.M.12, a 1960 elliptical oil-on-canvas work by the French Canadian automatist painter Jean Paul Riopelle. The whole point of the Quebec automatist movement was to prevent the conscious mind from having any creative control, letting instinct and the unconscious mind dominate creation. The result is the dynamic, spontaneous, unpolished, and impasto-rich work similar to the abstract expressionism of Jackson Pollock and Riopelle’s partner Joan Mitchell. While only predicted to sell for €50K to €70K, P.M.12 kept receiving bid after bid after bid until it hit close to six-and-a-half times the high estimate, with the gavel coming down at €450K / $489.7K (or €567K or $617K w/p). Similarly, Joan Miró’s bronze entitled Femme was only estimated to sell between €80K and €120K. So it came as a surprise when it went for three-and-a-half times that at €420K / $457K (or €529.2K / €575.9K w/p).

Christie specialists understood the collection’s value very well, estimating the entire sale to go for €20.62M to €30.4M. Because of the number of lots that sold above their estimates and that only five lots went unsold, the entire auction brought in over €2M more than expected. In total, the sale made €32.42M (or $35.1M). It was definitely a good day for Christie‘s, certainly making up for the underwhelming online sale the day before.

On January 29th, Sotheby's held The European Art Sale, Part II. Yet again, there were many works with condition issues, and surprisingly, several of them sold. I wonder if people buy works from simply viewing the images and not traveling to examine them in person. If so, when the paintings arrive, some of the buyers will probably wish they were not successful.

Christie’s European Art Online Sale

On Tuesday, Christie’s held their European Art online sale, but it was not exactly the best day for fans of nineteenth-century art. 30% of the lots sold below their estimates, while an additional 32% didn’t sell at all. Though estimated to bring in anywhere between $1.76M and $2.62M, sadly, the whole sale only amounted to $1.17M. But while the total may be a bit disappointing, some of the individual lots did very well.

Christie’s specialists did a good job predicting the auction’s top lots. The top spot went to Les dénicheurs Toscans by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Meaning The Tuscan Scouts, the scene shows a group of people trying to climb a tree. The background features the octagonal Baptistry of San Giovanni, letting the viewer know that Corot set his scene on the outskirts of Volterra, thirty-two miles southwest of Florence. While the title gives off some militaristic connotations, the figures are unlikely to be soldiers. They’re likely just a few boys having a bit of fun, adding just a touch of playfulness to an otherwise serene landscape. Corot’s Italian scene (which had some condition issues) fell nicely within its $100K to $150K estimate, selling for $110K (or $138.6K w/p).

Second place went to De Vijzelstraat te Enkhuizen by the Dutch cityscape painter Cornelis Springer. The street scene (measuring 19 x 26 inches) shows daily life in the small coastal town of Enkhuizen, twenty-eight miles northeast of Amsterdam. The Springer work was estimated to go for $100K to $150K, and it eventually sold for $100K (or $126K w/p). Finally, coming in third was the second of the three Corot paintings featured in the sale. This time, in his Saint-Quentin-des-Prés, he sets his scene in a northern French village rather than a Tuscan walled town. Corot shows a country road with a single cottage and a lone peasant woman. While many of Corot’s contemporaries focused on the French peasantry, Corot here concentrates instead on the rural environment. Christie’s experts believed it would go for anywhere between $120K and $180K, making it the highest-valued work in the pre-sale estimates. While it only brought in $100K (or $126K w/p), it still made the top three lots.

Seventeen (27%) of the auction’s lots went unsold in previous sales, but eleven of them finally sold this time around. While six of the eleven sold below their estimates, two sold within and three exceeded the Christie’s specialists’ expectations. Two of them not only exceeded their estimates, but they actually fell within the estimates given to them in their previous sales. The oil-on-canvas painting entitled Vanity by the British Victorian painter Thomas Edwin Mostyn was featured at two previous Christie’s sales. The Mostyn failed to sell at the October 2020 European Art sale with a $40K to $60K estimate, and then was later passed over a second time at the October 2021 European Art sale with a $20K to $30K estimate. This time, Vanity finally sold, surpassing its $18K high estimate, selling for $20K (or $25.2K w/p). Similarly, the Henri-Joseph Harpignies landscape Une vue près de Saint-Privé was featured in the same two Christie’s European Art sales as Mostyn’s Vanity. Like the Mostyn, it failed to sell at its $30K to $50K estimate in 2020, and its $20K to $30K estimate in 2021. And now, the Harpignies landscape joined Vanity’s when it surpassed the $18K high estimate and sold for $22K (or $27.7K w/p). So even though the sale as a whole may have failed to meet expectations, some of the auction’s highlights show that nineteenth-century works can still bring impressive amounts.

Seventeen (27%) of the auction’s lots went unsold in previous sales, but eleven of them finally sold this time around. While six of the eleven sold below their estimates, two sold within and three exceeded the Christie’s specialists’ expectations. Two of them not only exceeded their estimates, but they actually fell within the estimates given to them in their previous sales. The oil-on-canvas painting entitled Vanity by the British Victorian painter Thomas Edwin Mostyn was featured at two previous Christie’s sales. The Mostyn failed to sell at the October 2020 European Art sale with a $40K to $60K estimate, and then was later passed over a second time at the October 2021 European Art sale with a $20K to $30K estimate. This time, Vanity finally sold, surpassing its $18K high estimate, selling for $20K (or $25.2K w/p). Similarly, the Henri-Joseph Harpignies landscape Une vue près de Saint-Privé was featured in the same two Christie’s European Art sales as Mostyn’s Vanity. Like the Mostyn, it failed to sell at its $30K to $50K estimate in 2020, and its $20K to $30K estimate in 2021. And now, the Harpignies landscape joined Vanity’s when it surpassed the $18K high estimate and sold for $22K (or $27.7K w/p). So even though the sale as a whole may have failed to meet expectations, some of the auction’s highlights show that nineteenth-century works can still bring impressive amounts.

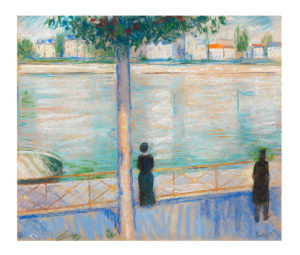

Bonhams Impressionist & Modern Sale

There were originally some pieces featured in Bonhams Impressionist & Modern sale last Thursday that I was very excited to see go across the block. But while the auction started strong, the entire thing turned out ever so slightly disappointing. The first six lots in a row sold over their estimates and contained the sale’s biggest surprises. The biggest surprise and the lot with the top hammer price was Edvard Munch’s Figures by the Seine in Saint-Cloud. It was created in 1890, not long after the artist left Norway to live in Paris for a brief period. While not displaying much of his later Symbolist works’ bold colors and sense of dynamism, the painting more than doubled its £120K high-end estimate, reaching £310K / $404.7K (or £390.9K / $510.3K w/p).

Only a few moments after the Munch sold, the sale’s third-best hammer price went to Louis Anquetin’s Elégantes, scène de rue. The moderately-sized pastel and charcoal on paper drawing fell within its estimate when it sold for £130K / $169.7K (or £164.1K / $214.2K w/p). It’s a street scene closeup, focusing on a young, red-headed woman in an olive green dress. The work’s main subject comes as a relief to the viewer since the background characters include a cadaverous blonde woman with an umbrella and a voyeuristic, mustachioed man in a top hat passing by in a horse-drawn cab.

The only notable work that did exactly as expected was the gouache, watercolor, ink, and gold leaf on paper work entitled Maternité. It was created in 1957 by the Japanese-French artist Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita during his second stint in France in the 1950s. Though the piece is a take on a Madonna and Child, Foujita chose not to give the work that name. Instead, he removes the religious aspect with the simple title, meaning Motherhood. The only obvious sign of religious influence is the child, with their arm extended and two fingers raised, resembling the Christian sign of benediction. The more subtle reference to Western religious artwork is the use of gold as the background. While it is reminiscent of the bright, sometimes gold, scenes of traditional Japanese paintings and folding screens from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the gold recalls its use for halos and other magical, miraculous, or supernatural elements in Western religious art. Even though it only sold for £150K / $195.8K (or £189.3K / $247.1K w/p), just short of £180K minimum estimate given by Bonhams specialists, it still took second place at the sale.

The only notable work that did exactly as expected was the gouache, watercolor, ink, and gold leaf on paper work entitled Maternité. It was created in 1957 by the Japanese-French artist Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita during his second stint in France in the 1950s. Though the piece is a take on a Madonna and Child, Foujita chose not to give the work that name. Instead, he removes the religious aspect with the simple title, meaning Motherhood. The only obvious sign of religious influence is the child, with their arm extended and two fingers raised, resembling the Christian sign of benediction. The more subtle reference to Western religious artwork is the use of gold as the background. While it is reminiscent of the bright, sometimes gold, scenes of traditional Japanese paintings and folding screens from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the gold recalls its use for halos and other magical, miraculous, or supernatural elements in Western religious art. Even though it only sold for £150K / $195.8K (or £189.3K / $247.1K w/p), just short of £180K minimum estimate given by Bonhams specialists, it still took second place at the sale.

While two-thirds of the lots either hit or exceeded their estimates, unfortunately the sale failed to fall within the £1.3M to £1.97M estimate. The entire auction fell short at £1.25M (or $1.64M), mainly because a few significant lots went unsold. The most highly-valued lot, the Joan Miró bronze and wood sculpture Tête et oiseau, did not even come close to its £300K to £500K pre-sale estimate. Meaning Head and bird, the work was conceived and created towards the end of Miró’s life. While created by one of the twentieth century’s greatest avant-garde artists, I could understand why it went unsold. The entire thing comes across as a combination of a ruined industrial monument and a deranged totem pole. The face on the work appears like a decaying, long-nosed clown mask hung up on a stick. Later on, buyers passed on the Édouard Vuillard painting Madame Jean Bloch et ses enfants estimated to go for £100K to £150K by Bonhams experts. Maybe it was the fact that Vuillard’s signature was stamped onto the canvas rather than properly signed that drove buyers away. Or perhaps some people might not want a family portrait of a family that is not their own. Who knows? But Bonhams may have overestimated the interest that modern art buyers would have in some of the selected works. Hopefully they’ll put a little more thought into it next time.

While two-thirds of the lots either hit or exceeded their estimates, unfortunately the sale failed to fall within the £1.3M to £1.97M estimate. The entire auction fell short at £1.25M (or $1.64M), mainly because a few significant lots went unsold. The most highly-valued lot, the Joan Miró bronze and wood sculpture Tête et oiseau, did not even come close to its £300K to £500K pre-sale estimate. Meaning Head and bird, the work was conceived and created towards the end of Miró’s life. While created by one of the twentieth century’s greatest avant-garde artists, I could understand why it went unsold. The entire thing comes across as a combination of a ruined industrial monument and a deranged totem pole. The face on the work appears like a decaying, long-nosed clown mask hung up on a stick. Later on, buyers passed on the Édouard Vuillard painting Madame Jean Bloch et ses enfants estimated to go for £100K to £150K by Bonhams experts. Maybe it was the fact that Vuillard’s signature was stamped onto the canvas rather than properly signed that drove buyers away. Or perhaps some people might not want a family portrait of a family that is not their own. Who knows? But Bonhams may have overestimated the interest that modern art buyers would have in some of the selected works. Hopefully they’ll put a little more thought into it next time.

Sotheby’s Old Masters Online Sale

In early February, I wrote about a Sotheby’s New York Old Masters sale where the star item was Sandro Botticelli’s Christ portrait known as The Man of Sorrows. While that sale brought in $76 million (or $91 million w/p), it barely crept past the total minimum estimate. I wondered whether Old Masters as a category was facing a brief period of decline, as some other analysts have noted. The sale, I wrote, “seemed a bit lackluster given the names attributed to the works.” But this week’s online Old Masters sale at Sotheby’s London location let us all know that the category is still chugging along (w/p = with buyers premium).

Sotheby’s specialists seemed very excited about one particular oil-on-panel work from 1540. It came out of the Antwerp workshop of the Dutch master Joos van Cleve. It’s a Madonna and child painting commonly known as The Madonna of the Cherries. In the sixteenth century, this was a particularly popular subject originally conceived by Leonardo da Vinci. While the Leonardo work is now lost, different copies and adaptations, like the one by Giampietrino, give today’s audiences a sense of what the original may have looked like. While the Van Cleve work is a lovely Madonna and child, it seems a little underwhelming compared to the Giampietrino copy. It’s even underwhelming compared to other Van Cleve versions of the subject. The Van Cleve Madonna of the Cherries from Hester Diamond’s private collection is miles better (in my opinion) than the one sold at Sotheby’s on Wednesday. One only needs to look at the titular cherries. In the Giampietrino and the other Van Cleve copies, the viewer can perceive their roundness, a gleam indicating a light source reflected in the skin. But with Van Cleve’s workshop, they’re nothing but small, red dots that look more like holly berries than cherries. There’s also the texture of the Madonna’s hair and the use of sfumato in the mountainous background. The work brought in £80K / $104.4K (or £100.8K / $131.6K w/p), hitting its high estimate right on the nose. But while the Van Cleve Madonna was the work most highly valued by Sotheby’s specialists, it reached only the third-highest hammer price for the sale. Two other pieces flew right past and exponentially exceeded their respective estimates.

The top spot for the sale, the biggest surprise of them all, belonged to A Peasant Woman Holding a Cockerel, created in the seventeenth century by an unknown artist likely from Northern Italy. While only estimated to go for £6K to 8K, dozens of bids allowed the simple portrait to sell for fifteen times its high estimate at £120K / $156.7K (or £176.4K / $230.3K w/p). Similarly, Sir Peter Lely’s Portrait of Letitia, later Lady Russell took second place after tripling its high estimate and selling for £90K / $117.5K (or £113.4K / $148K w/p). The Dutch-British portraitist created the work for Letitia Russell, the granddaughter of the Duke of Bedford. Both Letitia and A Peasant Woman were previously in the private collection of the Hill family, who have held the title Marquess of Downshire since the 1780s. While A Peasant Woman was a big enough surprise to come out on top, it wasn’t the only surprise at the auction. Peter Monamy’s nautical scene, The Royal Yacht Dublin, shows the titular ship used by Queen Anne, George I, and George II when travelling across the Irish Sea. A royal trip to Dublin didn’t take place too often, so it was more commonly used by the monarch’s Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Sotheby’s experts expected the work to fetch £8K maximum but reached over nine times that when it sold for £75K / $97.9K (or £94.5K / $123.4K w/p).

Towards the end of the sale, Sotheby’s mixed in some pieces from different genres, nineteenth-century paintings in this case. In all, the sale featured thirty-one nineteenth-century works. Most of them were sporting scenes by British painters like Ben Marshall and John Ferneley, with plenty of red-coated riders on horseback accompanied by their dogs. This was to increase the nineteenth-century pieces’ exposure to the Old Masters crowd since nineteenth-century paintings may not be doing particularly well at the moment. However, it’s also because, as time goes on, nineteenth-century works are slowly getting incorporated into the Old Masters categories. While it wasn’t the case a few decades ago, some of the great romantic artists like Delacroix and Géricault are now sometimes lumped into the Old Masters genre. So perhaps buyers will find more British sporting painters like John Frederick Herring regularly featured in Old Masters sales in the future.

Towards the end of the sale, Sotheby’s mixed in some pieces from different genres, nineteenth-century paintings in this case. In all, the sale featured thirty-one nineteenth-century works. Most of them were sporting scenes by British painters like Ben Marshall and John Ferneley, with plenty of red-coated riders on horseback accompanied by their dogs. This was to increase the nineteenth-century pieces’ exposure to the Old Masters crowd since nineteenth-century paintings may not be doing particularly well at the moment. However, it’s also because, as time goes on, nineteenth-century works are slowly getting incorporated into the Old Masters categories. While it wasn’t the case a few decades ago, some of the great romantic artists like Delacroix and Géricault are now sometimes lumped into the Old Masters genre. So perhaps buyers will find more British sporting painters like John Frederick Herring regularly featured in Old Masters sales in the future.

Sotheby’s experts expected the entire sale to bring in between £1.2M to £1.7M. The auction as a whole brought in £1.36M (or $1.8M), which is on the lower end of the estimate range, but within the estimate nonetheless. Despite many of the works being attributed to unknown artists (like A Peasant Woman), 58% of the 176 available lots hit or exceeded their estimates. So perhaps the greater integration of Old Masters and nineteenth-century genres could be the thing that revitalizes the two markets.

Bonham’s 19th Century & British Impressionism Sale

Last Wednesday’s 19th Century sale at Bonhams London certainly left one feeling astounded for various reasons. The one-hundred sixteen available lots came up a few hundred thousand pounds short, despite some works greatly exceeding their estimates, in some cases undeservedly so. Bonhams specialists seemed to have placed a good deal of their hope in Friedrich Nerly’s Venetian cityscape Bacino di San Marco, estimated at £200K to £300K. Unfortunately, that painting didn’t receive enough attention and was bought in. It seems like physical size was what attracted bidders to many works. The top spot was taken by Après le bal by Jan van Beers. The oil on canvas work measures 55.5 inches by 98.75 inches, making it nearly 4½ feet tall by more than 8 feet wide. Translating to After the Ball, it shows a sleeping young woman lying on what appears to be a sofa draped in furs. The woman is completely nude, with the remnants of the previous night’s events unceremoniously discarded on the floor next to her: her dress, her stockings, her shoes, a bouquet of flowers, a cigarette case, and other assorted things that presumably she threw on the floor in an exhausted stupor after returning home. The only things that remain on her person are some thin bracelets and a choker necklace. The Van Beers work, while only expected to bring in £60K to £80K, sold for £255K / $335K (or £319K / $419.1K w/p). Not only was it the painting’s size that caused it to bring in over three times its estimate, but I think it’s the work’s relatability. Because who among us hasn’t at one point felt the same way as the painting’s subject? Throwing all your stuff on the floor, not even putting stuff away, diving right into bed, or just the nearest comfortable flat surface.

Last Wednesday’s 19th Century sale at Bonhams London certainly left one feeling astounded for various reasons. The one-hundred sixteen available lots came up a few hundred thousand pounds short, despite some works greatly exceeding their estimates, in some cases undeservedly so. Bonhams specialists seemed to have placed a good deal of their hope in Friedrich Nerly’s Venetian cityscape Bacino di San Marco, estimated at £200K to £300K. Unfortunately, that painting didn’t receive enough attention and was bought in. It seems like physical size was what attracted bidders to many works. The top spot was taken by Après le bal by Jan van Beers. The oil on canvas work measures 55.5 inches by 98.75 inches, making it nearly 4½ feet tall by more than 8 feet wide. Translating to After the Ball, it shows a sleeping young woman lying on what appears to be a sofa draped in furs. The woman is completely nude, with the remnants of the previous night’s events unceremoniously discarded on the floor next to her: her dress, her stockings, her shoes, a bouquet of flowers, a cigarette case, and other assorted things that presumably she threw on the floor in an exhausted stupor after returning home. The only things that remain on her person are some thin bracelets and a choker necklace. The Van Beers work, while only expected to bring in £60K to £80K, sold for £255K / $335K (or £319K / $419.1K w/p). Not only was it the painting’s size that caused it to bring in over three times its estimate, but I think it’s the work’s relatability. Because who among us hasn’t at one point felt the same way as the painting’s subject? Throwing all your stuff on the floor, not even putting stuff away, diving right into bed, or just the nearest comfortable flat surface.

For the second-place work, physical size may have again been a factor. La Opere, Campiña Romana by Ramón Tusquets y Maignon is a massive painting, measuring 4 feet tall by 8½ feet wide. And it’s an incredible work, showing clear inspiration from French Realist works by Courbet and Millet. But what Bonhams specialists highlight is that the work, showing Roman peasants working the fields, would have been impossible to create if Tusquets had not been intimately familiar with the countryside of Lazio, just outside Rome. The color of the sunlight, the texture of the soil, and the dress of the figures were all executed with painstakingly detailed accuracy. So it’s not surprising that it hit its £150K to £200K estimate, selling for £170K / $223.3K (or £212.75K / $279.5K w/p).

The third place was a smaller painting, but one that caught my attention when I first browsed the lots before the sale. While John Atkinson Grimshaw may be best known for his moonlit nightscapes, In the Autumn’s Waning Glow is a beautiful twilight scene showing a red and gold, leaf-covered, Northern English village road. Estimated at £120K to £180K by Bonhams experts, the Grimshaw hit £150K / $197.1K (or £187.75K / $246.6K w/p).

While the Van Beers work taking the top spot came as a surprise to many, it was by no means the biggest surprise of the sale. That role was taken up by a rather unimpressive oil on canvas work by the relatively obscure Russian-Jewish artist Isaak Lwowitsh Asknasij. The Rabbi and his daughter may be one of the most damaged works I have ever seen across the auction block. The canvas is completely covered with a spider web of cracks, so much so that I had to get a second opinion as to whether or not they were intentionally part of the original painting. The £5K to £7K estimate given by Bonhams experts is incredibly generous, to say the least. This is why I sat in disbelief as bid after bid came in, bringing up the hammer price to £42K / $55.1K (or £52.75K / $69.3K w/p). My faith in humanity was later restored when the sale’s other surprise came up. John Emms’s Foxhounds and a hunt terrier was estimated to go for anywhere between £10K and £15K. But of course, similar to the Internet, if something has a couple of cute dogs, it’s bound to get more attention than expected. After a few minutes, the bidding had already soared past the estimate, landing at £63K / $82.8K (or £79K / $103.8K w/p).

While the Van Beers work taking the top spot came as a surprise to many, it was by no means the biggest surprise of the sale. That role was taken up by a rather unimpressive oil on canvas work by the relatively obscure Russian-Jewish artist Isaak Lwowitsh Asknasij. The Rabbi and his daughter may be one of the most damaged works I have ever seen across the auction block. The canvas is completely covered with a spider web of cracks, so much so that I had to get a second opinion as to whether or not they were intentionally part of the original painting. The £5K to £7K estimate given by Bonhams experts is incredibly generous, to say the least. This is why I sat in disbelief as bid after bid came in, bringing up the hammer price to £42K / $55.1K (or £52.75K / $69.3K w/p). My faith in humanity was later restored when the sale’s other surprise came up. John Emms’s Foxhounds and a hunt terrier was estimated to go for anywhere between £10K and £15K. But of course, similar to the Internet, if something has a couple of cute dogs, it’s bound to get more attention than expected. After a few minutes, the bidding had already soared past the estimate, landing at £63K / $82.8K (or £79K / $103.8K w/p).

While about 40% of the one-hundred sixteen lots hit or exceeded their estimates, nearly an equal amount went unsold. This caused the auction to fail to meet the presale estimates. Though Bonhams specialists were hoping for anywhere between £1.9M and £2.9M, the sale was a couple hundred thousand pounds short, reaching only £1.7M (or $2.3M).

Sotheby’s Paris Modern & Impressionist Online Sale

Sotheby’s Paris had remarkable back-to-back days at the end of March. They had the second half of the Robert and Nadine Schmit collection on Thursday. The following day, they held their modern and impressionist online sale, full of great surprises (w/p = with buyer’s premium). The top spot went to En revenant des Champs by Gustave van de Woestyne. The man and woman looking over their shoulders at the viewer, put onto canvas by a relatively obscure Belgian expressionist, sold for €240K / $263.7K (or €302.4K / $332.3K w/p). While it had the highest hammer price of the sale, it sold for just short of its minimum pre-sale estimate of €250K.

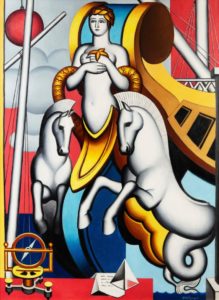

Some other high price tags included that of Jean Metzinger’s Figure et chevaux de proue. The large oil on canvas painting was stunning, showing the nude torso of a woman decorating the bow of a ship. Gold completely envelops her, including the gold detailing of the ship’s bow, a golden starfish resting on her hand, and something draped over her arms and around her back resembling a golden, scaled boa scarf. Her hair is also gold, which I originally mistook for golden laurels sitting atop her head. Despite the title saying horses accompany her, the two equine figures flanking her are actually hippocampi, a half-horse half-fish combination from Greek mythology. This is a quite fitting continuation of the nautical theme. All three figures are completely white, making them almost seem like they’re sculpted from marble on the façade of a Greek temple or an Art Deco skyscraper. Metzinger’s painting eventually sold for €190K / $208.7K (or €239.4K / $263K w/p).

Some other high price tags included that of Jean Metzinger’s Figure et chevaux de proue. The large oil on canvas painting was stunning, showing the nude torso of a woman decorating the bow of a ship. Gold completely envelops her, including the gold detailing of the ship’s bow, a golden starfish resting on her hand, and something draped over her arms and around her back resembling a golden, scaled boa scarf. Her hair is also gold, which I originally mistook for golden laurels sitting atop her head. Despite the title saying horses accompany her, the two equine figures flanking her are actually hippocampi, a half-horse half-fish combination from Greek mythology. This is a quite fitting continuation of the nautical theme. All three figures are completely white, making them almost seem like they’re sculpted from marble on the façade of a Greek temple or an Art Deco skyscraper. Metzinger’s painting eventually sold for €190K / $208.7K (or €239.4K / $263K w/p).

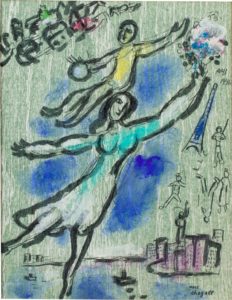

Third place was actually a tie between a sculpture and a painting. Tête, oiseau by Joan Miró sold for €150K / $164.7K (or €189K / $207.6K w/p), while a Marc Chagall painting called La Danse reached the same price. Both are very typical works for their respective artists. The Miró bronze was spotted with patches of green oxidation, most noticeable where the artist made a very simplistic frowning face right in the middle of the rough, round sculpture. The Chagall work, done with gouache and pencil on paper, shows a pair of figures dancing, almost floating over a river, with several smaller figures surrounding the Eiffel tower off to the side. It may not be as striking or colorful as some other works by the artist of the same name, but it’s still exemplary of the fantasy, or rather the dream sequence snapshots, that Chagall often made the subject of his works.

Third place was actually a tie between a sculpture and a painting. Tête, oiseau by Joan Miró sold for €150K / $164.7K (or €189K / $207.6K w/p), while a Marc Chagall painting called La Danse reached the same price. Both are very typical works for their respective artists. The Miró bronze was spotted with patches of green oxidation, most noticeable where the artist made a very simplistic frowning face right in the middle of the rough, round sculpture. The Chagall work, done with gouache and pencil on paper, shows a pair of figures dancing, almost floating over a river, with several smaller figures surrounding the Eiffel tower off to the side. It may not be as striking or colorful as some other works by the artist of the same name, but it’s still exemplary of the fantasy, or rather the dream sequence snapshots, that Chagall often made the subject of his works.

There were also a few surprises along the way, where the Sotheby’s specialists dramatically underestimated how much some buyers would be willing to drop that day. In the middle of the sale, works by Berthe Morisot (est. €12K to €18K; €55K / $60.4K hammer, or €69.3K / $76.1K w/p) and Paul Sérusier (est. €1K to €1.5K; €5K / $5.5K hammer, or €6.3K / $6.9K w/p) reached triple their high estimates. But the real shock came a little while later when Jane Graverol’s 1959 oil-on-board painting La déesse raison went across the block. While only estimated to sell for anywhere between €2.6K and €3.5K, the work by the Belgian surrealist climbed up and up until it reached a hammer price of €38K / $41.8K (or €47.8K / $52.6K w/p), nearly eleven times the high estimate. This was also an auction record for Jane Graverol. Her highest-valued work before La déesse raison was her 1954 oil-on-board work La chair de vérité, which similarly blew away its meager £3K to £5K estimate at a 2018 Sotheby’s sale with a £18K / $25.7K hammer price.

There were also a few surprises along the way, where the Sotheby’s specialists dramatically underestimated how much some buyers would be willing to drop that day. In the middle of the sale, works by Berthe Morisot (est. €12K to €18K; €55K / $60.4K hammer, or €69.3K / $76.1K w/p) and Paul Sérusier (est. €1K to €1.5K; €5K / $5.5K hammer, or €6.3K / $6.9K w/p) reached triple their high estimates. But the real shock came a little while later when Jane Graverol’s 1959 oil-on-board painting La déesse raison went across the block. While only estimated to sell for anywhere between €2.6K and €3.5K, the work by the Belgian surrealist climbed up and up until it reached a hammer price of €38K / $41.8K (or €47.8K / $52.6K w/p), nearly eleven times the high estimate. This was also an auction record for Jane Graverol. Her highest-valued work before La déesse raison was her 1954 oil-on-board work La chair de vérité, which similarly blew away its meager £3K to £5K estimate at a 2018 Sotheby’s sale with a £18K / $25.7K hammer price.

In total, ninety-three of the one hundred forty-one lots, or about two-thirds, hit or exceeded their estimates. Thirty-five lots were either bought in or withdrawn. The lots that did sell took in €3.2M / $3.5M, or a little over €4M / $4.5M w/p. This falls nicely into the €2.9M to €4.1M (or $3.2M to $4.5M) pre-sale estimate Sotheby’s specialists gave.

____________________

Deeper Thoughts

By: Nathan

Lost in the Basement: A Rediscovered Masterpiece at an Australian Museum

Cleaning out the basement can be a hassle for anyone that has one. Things pile up, and it’s easy to forget what you have down there. But it may be difficult to forget that there’s a masterpiece from the Dutch Golden Age just lying around collecting dust. But that’s what recently happened at an Australian museum when they decided to go through an old storeroom.

Cleaning out the basement can be a hassle for anyone that has one. Things pile up, and it’s easy to forget what you have down there. But it may be difficult to forget that there’s a masterpiece from the Dutch Golden Age just lying around collecting dust. But that’s what recently happened at an Australian museum when they decided to go through an old storeroom.

The Woodford Academy is located in a small village in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales, about an hour outside of Sydney. The cluster of buildings was originally constructed as an inn before becoming a private residence and then a boarding school. In 1979, the property was donated to the National Trust of Australia and turned into a museum. As part of an ongoing art restoration project, the Woodford Academy sent around thirty paintings to conservators, who later found a very exciting signature on the still-life in question. While the National Trust now knows that it’s a still-life created around 1640, it is not entirely known who created the painting despite the signature. It could be Willem Claesz. Heda, considered one of the most prolific still-life painters of the Dutch Golden Age. However, the work could also be by his son Gerret Willemsz. Heda, whose signature is very similar to his father’s. Because of this similarity, art historians attributed nearly all of the younger Heda’s work to his father before 1945. Some art historians theorize that the still-life in question could be a collaboration between the two. But that’s all we have right now: theories.

The untitled still-life shows a table with a half-eaten pie, some glassware, an overturned goblet, a bread roll, and a plate of nuts. This sort of still-life painting is very similar to a style known as vanitas, which was incredibly popular in the Netherlands throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Masters of still-life like Pieter Claesz and Harmen Steenwijck became incredibly well known for these works. They often include a table set with timepieces, burnt-out candles, instruments, half-eaten food, mirrors, and, most iconically, skulls. They convey messages about our own mortality, and that we all must make good decisions on how we spend our time. In many of Heda’s still-lifes, including the one discovered at Woodford Academy, one of the plates is set on the table’s edge, part of it hanging off. According to the National Trust’s collections manager Rebecca Pinchin, this continues the vanitas themes, conveying “the transient nature of life – one minute you have comfort and pleasure, the next you can fall into bad times.”

It’s believed that the painting arrived in Australia because of Alfred Fairfax, who probably bought the work while he owned Woodford House as his private retreat until 1897. While it was originally said to be worth $200K, experts’ estimates shot up to $5 million after specialists discovered the signature. It’s not unheard of for a work by the older Heda, but it may be more reasonable given the draw of the story behind it. It is no doubt an incredible find, and will likely draw art lovers and history buffs alike to a regional museum. The Heda still-life will be displayed at the Woodford Academy for the Australian Heritage festival starting on May 14th.

Yves Klein’s Ingenious Marketing Scheme

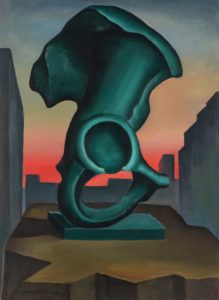

Now you see it…. now you don’t. Or maybe you never saw it at all! Yves Klein came up with an ingenious marketing scheme back in 1958 when he opened an exhibit in Paris titled “The Void,” which featured invisible artwork. Klein continued ‘creating’ these pieces until he died in 1962.

Now you see it…. now you don’t. Or maybe you never saw it at all! Yves Klein came up with an ingenious marketing scheme back in 1958 when he opened an exhibit in Paris titled “The Void,” which featured invisible artwork. Klein continued ‘creating’ these pieces until he died in 1962.

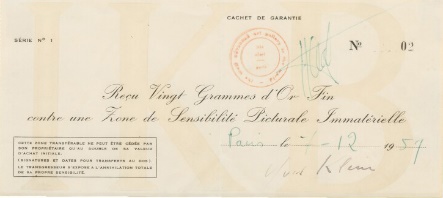

Visitors came to the exhibit to see Klein’s latest collection and purchased the invisible pieces, known as ‘zones,’ for gold bullion (20 grams of gold.) Klein gave each purchaser a signed receipt for his conceptual artwork as proof of ownership. Not many receipts remain because, after the purchase, Klein offered his clients a choice to keep their receipt or participate in a bit of performance art. Klein would have the buyer burn the receipt, and he would dump half the gold that was paid for it into the Seine River to rebalance the ‘natural order’ that was unbalanced by the sale. Klein’s performance was always in the presence of an art critic or distinguished dealer, an art museum director, and at least two witnesses.

One of the purchasers, Jacques Kugel, purchased a piece in 1959 titled Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility and chose to keep his receipt. The ‘artwork’ and receipt were exhibited at museums and galleries across Europe. Eventually, ‘they’ were purchased by art advisor and curator Loïc Malle in 1986. More than a hundred items from Malle’s collection were auctioned, including the receipt and, I assume, the artwork (which is invisible). The receipt was expected to bring €280K to €500K ($330K to $550K) and exceeded the estimate when it sold for €850K ($1.2 M w/p). I hope the new owner enjoys countless hours staring at his unique artwork.

NFTS’ Deep Carbon Footprint

Many have hailed non-fungible tokens (NFTs) as the future of art and art collecting. But there are just as many who astutely highlight some of the drawbacks. I’ve previously written about how the technology behind NFTs can make it easier for scammers to sell digitized artworks without the original creator’s permission. There’s also the budding NFT collector culture that rewards a lack of creativity, with monkeys, lions, or other animals generated and customized by computer code rather than anything resembling a creative process. But not many people are talking about the real-world impact of NFTs, namely the environmental cost. And more people were made aware of that when it was reported that the British Museum used up nearly sixty years’ worth of power just on their NFT project.

Many have hailed non-fungible tokens (NFTs) as the future of art and art collecting. But there are just as many who astutely highlight some of the drawbacks. I’ve previously written about how the technology behind NFTs can make it easier for scammers to sell digitized artworks without the original creator’s permission. There’s also the budding NFT collector culture that rewards a lack of creativity, with monkeys, lions, or other animals generated and customized by computer code rather than anything resembling a creative process. But not many people are talking about the real-world impact of NFTs, namely the environmental cost. And more people were made aware of that when it was reported that the British Museum used up nearly sixty years’ worth of power just on their NFT project.

Because the British Museum is a public institution, it doesn’t take a Bob Woodward-level of investigation to find out about this. Partnering with the digital arts organization LaCollection, the British Museum has minted over two thousand NFTs to date. They are mainly digitized versions of their collection highlights, like the paintings of J.M.W. Turner. But while some critics will liken an NFT to a very expensive JPEG image, one of the main differences is that NFTs take so much more computer power to mint and exchange. Experts in cryptocurrency and NFTs estimate that, on average, a single transaction, a single change to the blockchain, uses up enough electricity to emit around 330 lbs. of carbon dioxide. This is around the same amount the average American home uses over nine days. Adding everything up, the British Museum and their partners have used up enough electricity to put out 348 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, enough to power that same home for fifty-seven years. But some estimates say the emissions are much higher, around 900 tons. While LaCollection has promised to plant one tree for every NFT it mints, that won’t exactly provide much of a counterbalance. The average tree does absorb about one ton of carbon dioxide over one hundred years. Not exactly the pressing sort of solution we all need right now, I would think. Similarly, NFT artists like Mike Winkelmann, also known as Beeple, promised to invest in renewable energy and conservation projects. Environmentally-conscious artists not involved with NFTs, like Ashley Grace, are very pessimistic about these attempts at balance, calling them an “ecological nightmare pyramid scheme”.

The British Museum does have a sustainability policy, but it is still a relic from 2007. It promises “the elimination or reduction of any detrimental impact that [the museum’s] activities might have on the environment.” With the current pandemic placing a financial strain on many major art institutions, places like the British Museum will auspiciously forget or possibly just flat-out ignore their previous promises. While the need for funds is understandable, this has not stopped other British art institutions from cutting off ties with environmentally-harmful practices and organizations, like the National Portrait Gallery’s severing ties with British Petroleum in February. On the other hand, the British Museum has gone whole-hog into the NFT world, and they have continually balked at cutting ties with BP. Thankfully, some in the cryptoverse advocate moving cryptocurrency-mining and NTF-minting computers onto grids powered by renewable sources. There’s also some support for changing NFTs from being backed by Ethereum cryptocurrency to something that consumes less energy and is a little more sustainable. While these ideas have been floating around for a bit, they’re still just ideas. And it can sometimes be excruciating to remind some people that while NFTs and bitcoin are intangible things, the Earth is very much real.

Keith Haring’s Newest Confrontation

The Nova Southeastern University Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale is one of Florida’s finest and most underrated museums. While its collection houses over six thousand Picasso ceramics, the museum is also known as the largest collection of art from the CoBrA abstract movement anywhere in the United States. A good chunk of that CoBrA collection comprises works by the Belgian painter Pierre Alechinsky. The museum’s latest exhibition, Confrontation, displays Alechinsky’s work alongside that of the modern street art master he inspired: Keith Haring.

The Nova Southeastern University Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale is one of Florida’s finest and most underrated museums. While its collection houses over six thousand Picasso ceramics, the museum is also known as the largest collection of art from the CoBrA abstract movement anywhere in the United States. A good chunk of that CoBrA collection comprises works by the Belgian painter Pierre Alechinsky. The museum’s latest exhibition, Confrontation, displays Alechinsky’s work alongside that of the modern street art master he inspired: Keith Haring.

Keith Haring’s simple figures are some of the most recognizable images of twentieth-century art. His work, much of it known for its refinement and reutilization of childlike notebook doodles, has been used to tell stories, spread messages, and advocate for various causes. “It was made for lots of people,” Haring said when talking about his work. “You don’t have to know anything about art to appreciate it, or look at it. There aren’t any hidden secrets or things that you’re supposed to understand.” Haring completed many magnificent public works to draw attention to several causes during his lifetime. These included HIV and AIDS, the apartheid regime in South Africa, and the crack epidemic. To promote sex education and safe sex in 1989, he created the mural Once Upon a Time… at the New York Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center. Although it’s been over thirty years since his death, Keith Haring and his works remain a relevant part of our cultural lexicon.

Pierre Alechinsky came of age during the Second World War and, inspired by the works of French informalists and surrealists like Jean Dubuffet and Max Ernst, studied art in Brussels. It didn’t take long before he was one of the founders of CoBrA, an avant-garde movement composed of Western Europe’s top abstract artists based out of cities like Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam (hence the name of the group). Alechinsky started working as an artist professionally in 1951 and has gone on to stage solo exhibitions in the United States, Japan, Brazil, and across Europe. He still lives and works in Paris, making him the last living member of CoBrA at the age of 95.

When Keith Haring was 19-years-old living in Pittsburgh, he studied at the Ivy School of Professional Art while also working on the maintenance crew at the city’s Center for the Arts. There, he was able to view exhibitions and attend lectures for free. One such exhibition included two hundred works by Pierre Alechinsky, and it seemed to have impacted Haring. By the next year, he managed to get his first solo exhibition before moving to New York and becoming the 1980s street artist as we know him now. Alechinsky’s influence on Haring’s work is clear when viewed side-by-side. Bold lines, the use of color, and a contempt for convention. While oil-on-canvas is often the norm for painters, both Alechinsky and Haring used acrylic paints. Alechinsky preferred using paper for his works, while Haring ditched a traditional canvas in favor of blank advertising space on subway platforms, the walls of Greenwich Village, and tarps bought from hardware stores.

While peoples’ focus on Keith Haring is nearly always limited to his broad cultural appeal or the messages he conveyed, not much has been done on where he stands in terms of the artistic genealogy; the connections that result in one generation of artists influencing another. Arielle Wolens, the exhibition’s curator, summed up that point very precisely: “We really wanted to show the ways that artists learn from each other, as well as the way artists learn from museums.” Confrontation will be open at the NSU Art Museum until October 2nd.

Setting the Record Straight About “Russian” Art

Ever since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24th, many institutions have sought to further scrutinize their relationship with all things Russian. London’s National Gallery is one of the most recent organizations to do just that, even if it was in a small gesture: they righted a century-old wrong by correcting the name of a drawing by Edgar Degas from Russian Dancers to Ukrainian Dancers.

Ever since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24th, many institutions have sought to further scrutinize their relationship with all things Russian. London’s National Gallery is one of the most recent organizations to do just that, even if it was in a small gesture: they righted a century-old wrong by correcting the name of a drawing by Edgar Degas from Russian Dancers to Ukrainian Dancers.

The Russian Empire, and the Soviet Union that followed it, were enormous landmasses, constituting about one-sixth of all land on Earth at any given time. And while it’s easy to label anything from those two now-dead world powers as simply “Russian”, it’s important to remember their diversity. Whether under czarism or communism, only around half of the population was actually Russian. Everyone else self-identified with one of the many, smaller ethnic groups, like Armenians, Georgians, Belarussians, and, of course, Ukrainians. Ukrainians were always the largest ethnic minority in the Empire and the USSR, making up anywhere between fifteen and twenty percent of the total population depending on the year. But because everything in the Empire and the USSR was frequently grouped into a single, Russian monolith, Ukrainian culture was, and still is, often either confused for Russian culture or grouped with Russian culture. This is done both intentionally (by Russians) and accidentally (by non-Russians). The latter of the two is likely what happened when Edgar Degas executed his 1899 pastel-on-paper work Russian Dancers.

The debate about whether to rename the work from Russian Dancers to Ukrainian Dancers precedes the Russian invasion. For several years, scholars and activists have pointed out that it was likely a Ukrainian folk dance group that Degas observed in Paris. The clearest piece of evidence in support of the name change is the ribbons in the dancers’ hair being blue and gold. If you’ve been living under a rock for six weeks, those are the national colors of Ukraine, which have their origins in the medieval period but have been used as a symbol of the Ukrainian people since 1848. Some have claimed that the continued use of the term “Russian” in the title is just one example of Russia’s continued appropriation of, and hegemony over, all Slavic cultures, as well as everyone else’s disinterest in the issue. The term “laziness” has understandably been thrown around. According to statements from the National Gallery, the current Russian war in Ukraine has allowed them to officially change the name of the piece due to a greater sense of awareness of Ukrainian culture and identity.

Ever since the National Gallery made its announcement on Monday, many people have flocked to social media, either to applaud or criticize the decision. It appears that many of the critics do not understand the context surrounding this decision. Many seem to have just read the headlines and thought this is some sort of political stunt, or perhaps the museum leadership is jumping on the political correctness bandwagon. Some claim that it’s okay to refer to the subjects as Russian, since Ukraine didn’t exist as a country when Degas completed the work. Well, see my comments above. Lack of statehood does not negate the existence of culture and identity. It’s easy for Russian people to say this sort of stuff because it’s Russian political and cultural leaders who advocate a sort of pan-Slavism that invalidates a lot of non-Russian Slavic culture. It’s the same thing that happens when Irish people get confused for Brits. Or Canadians get confused for Americans. Or Austrians for Germans. Or New Zealanders for Australians. I could go on and on. But it’s this sort of thinking that instills a sort of collective humiliation and fatigue, to never being recognized as a culture in your own right.