COMMENTS ON THE ART MARKET

Two Upcoming Gallery Exhibitions

Opening Night – November 9th at 4:30 pm

Chuckie’s Grand Adventure

Opening on November 9th at 4:30 pm and continuing through December 8th, Stuart Dunkel’s solo exhibition Chuckie's Grand Adventure. Chuckie comes to life in each painting as he explores all that the world has to offer… from some of the most iconic landmarks around the globe to everyday items, the little mouse is taking it all in.

Stuart Dunkel will be attending the opening.

____________________

Small Works Show

Also opening on November 9th, at 4:30 pm, is our yearly holiday gift exhibition Small Works Show. The exhibition will feature new and exciting works, all 12 x 12 inches and smaller, by many of your favorite artists including Ben Bauer, Ryan Brown, Jon Burns, Todd Casey, Mark Daly, Gail Descoeurs, Hammond, Gregory Frank Harris, Lucia Heffernan, Timothy Jahn, Alexandra Klimas, Shana Levenson, Leo Mancini-Hresko, Andrew Orr, Dave Palumbo, and Ken Salaz.

Both shows will run concurrently.

Opening Night

Thursday, November 9: 4:30 pm – 8:00 pm

General Show Days

Monday – Friday

November 10 – December 8

10:00 am – 5:00 pm

Please let us know if you would like to attend the opening.

We need to be sure we have enough goodies for everyone!

____________________

Antiques + Modernism Show Winnetka

We invite you to join us at the 51st Antiques + Modernism Show! The event begins with an exciting Preview Party on the evening of November 2 at the Winnetka Community House and continues through the weekend.

This show features a wide range of styles, from classic to modern designs. You can explore exquisite home furnishings, accessories, art, clothing, jewelry, and more, all brought by respected dealers from across the country. The event's long history and outstanding reputation make it a highly anticipated shopping experience. We hope to see you there!

If you would like complimentary General Admission tickets, please send an email to: info@rehs.com

____________________

Stocks & Crypto

As has become customary for our newsletter, we don’t have the patience to wait until the end of the month, so here’s how the markets performed through most of October…

While September is historically the worst month for stocks, on average, October is the spookiest… it holds the crown as the most volatile month. With heightened uncertainty at this time of the year, investors need to brace themselves. By many accounts, Americans have grown more pessimistic about the economy’s future… just last Friday, the University of Michigan released its latest survey results, which showed consumer sentiment declined 6% this month alone! At the same time, short-term and long-term inflation expectations rose in October, so the Fed may maintain higher rates for longer than initially planned. As I’ve said in the past, inflation doesn’t simply impact consumers… consumer spending has a ripple effect on corporate profits and, in turn, influences stock prices. As for numbers themselves, all three major indexes were down in October… the Dow dropped 3.1%, the NASDAQ slid 4.34%, while the S&P500 shed 3.9%.

As for currencies and commodities, both the Pound and Euro traded in a tight range, which fluctuated +/- 1% throughout the month… the Pound currently sits down 0.75% relative to the Dollar, while the Euro is essentially even through October. Crude has experienced moderate volatility and currently sits down more than 4% this month. Conversely, gold has seen a steady rally past the $2K threshold, which is good for a gain of more than 9%!

Turning to the blockchain, crypto was doing crypto things… Bitcoin decided to go off for seemingly no reason. Mid-month, it was actually down about 1%... less than 10 days later, it was up more than 25%. It’s given a bit back, but it’s still up more than 22% this month – one analysis shows that much of these gains occurred during US trading hours, signaling that US institutions could be embracing news that a spot Bitcoin ETF appears imminent. Unfortunately, Ethereum and Litecoin got themselves into a hole early in October, so even with the Bitcoin surge, the numbers aren’t in the same ballpark… the surge buoyed Ethereum back to positive territory, currently up 2.3%, while Litecoin is down 2.4%.

While there is nothing blatantly tragic about any of this, at the moment, things don’t seem to be trending in a positive direction … I mean, we didn’t even talk about the fact that the House of Representatives spent the month fighting among themselves, or how the Middle East has spiraled to the brink of WWIII. I’ll just be here hoping humanity gets its shit together… I’m getting sick of all the bad news.

____________________

Really!?

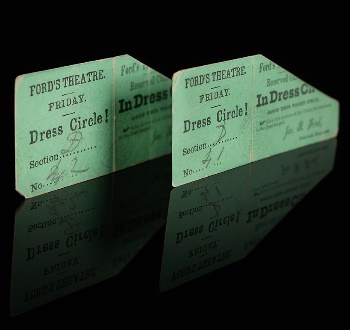

Who Wants Theatre Tickets to a Show that Closed in 1865?

Who wants theatre tickets to a show that closed in 1865? At a recent auction, an anonymous buyer made a remarkable acquisition by securing a pair of tickets for the April 14, 1865 performance of ‘My American Cousin’ at Ford’s Theatre – an event forever etched in American history due to the tragic assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

During that ill-fated performance, President Abraham Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, occupied the presidential box, completely unaware that they were moments away from becoming central figures in a defining historical moment. It was during the play’s third act that John Wilkes Booth, a celebrated actor with previous appearances on the same stage, dramatically entered the scene. His entry into the president’s box irrevocably altered the course of history.

Despite the passage of time, these tickets to Ford’s Theater’s dress circle remain surprisingly well-preserved, bearing the creases and folds of their journey through history. They serve as tangible connections to that fateful and somber night, allowing us to reach back through the years and touch the past.

The tickets sold for just 75 cents back in 1865. In 1992, these tickets were purchased at an auction by Steve Forbes. He had inherited the historical manuscript collection of his father, Malcolm S. Forbes, a discerning collector with a deep appreciation for historical memorabilia. Recognizing their historical significance, Forbes chose to part with them in 2002, consigning them to Christie’s New York. The result was nothing short of astonishing, as the tickets commanded a remarkable $71.5K (or $83.7K w/p), greatly exceeding the initial valuation range of $10,000 to $15,000.

In a fascinating turn of events, these very same tickets reemerged on the auction scene, once again making history by surpassing their estimated value. This time around, the estimate was in excess of $100K. But when the show came to an end, they sold for more than double, garnering $210K ($262.5K w/p). Their journey through time, changing hands between collectors, underscores not only their rarity but also the enduring fascination that people have with preserving and commemorating moments of profound historical importance.

Berlusconi Art Collection Deemed Worthless

The late former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi has a complicated legacy. Even after his death this past June, he continues complicating things, mainly through his large estate. Berlusconi was worth approximately €6 billion at his death, made primarily in media and broadcasting. As the third-wealthiest person in Italy, he lived an extravagant lifestyle, accompanied by a seemingly extravagant art collection. However, in examining his collection, art critics and specialists now tell us Berlusconi’s collection is worth far less than expected.

Some of the details surrounding the Berlusconi collection make it seem very impressive. The former prime minister owned about 25,000 pieces of art, which he kept mainly in a 34,000-square-foot warehouse near his mansion outside of Milan. The warehouse costs €800,000 to maintain every year. But Berlusconi’s heirs might have been disappointed to learn that all those thousands of pieces are worth around €20 million. Of course, that’s not exactly chump change, but when you remember that this collection is absolutely massive, it doesn’t seem like that much. The average value of each work is around €800. Many people get the impression that well-known people who collect art are different kinds of connoisseurs, like Paul Allen or Harry and Linda Macklowe. However, Berlusconi was a very different kind of collector. According to those who knew him, he was an impetuous impulse-buyer. Much of his collection consists of cityscapes, mainly of Milan or Paris, as well as religious paintings and female nudes. He was particularly fond of female nudes since he often brought them out to show people the same way a boy might show his friends a page torn out of a Playboy. He allegedly gifted some of these works to Vladimir Putin and Viktor Orbán. Berlusconi sought to become a prominent collector but valued quantity over quality. Most of his collection is not in good condition. Many works are extensively damaged by woodworms. Berlusconi’s children are now weighing their options since the extermination cost would be more than the collection’s value.

That is not to say that Berlusconi owned nothing but complete garbage. Out of all 25,000 works, art critic Vittorio Sgarbi commented that only around six or seven paintings have any artistic or monetary value. Berlusconi clearly knew this since he kept these paintings, including a Titian and a Rembrandt, in his main residence rather than the warehouse. Berlusconi acquired these works when he was younger and bought them from galleries and collectors. However, most of his nearly worthless collection came from late-night TV auctions that Berlusconi frequently watched starting around 2018. Because of its low value and the woodworm problem, there were even reports that Berlusconi’s five children preferred to burn most of the collection since they didn’t see the point in keeping or selling it. However, a family spokesperson has said that the children and Berlusconi’s partner Marta Fascina are in the process of selecting what works they wish to keep. The fate of the other pieces is yet to be determined.

Modigliani’s Note Makes an Impression

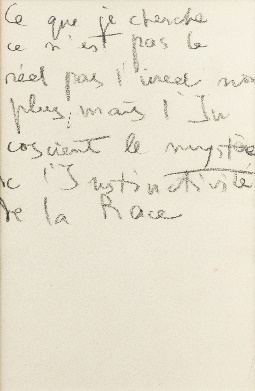

The Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani is always popular at auction. Normally it’s his paintings that fetch large sums, but a recent Sotheby’s sale saw bidders fighting over a scrap of paper.

Modigliani was born in Livorno, Italy, on July 12, 1884, and passed away in Paris on January 24, 1920. He is renowned for his unique and iconic portraits characterized by elongated features, almond-shaped eyes, and a sense of melancholy. His work is associated with the modernist and figurative art movements of the early 20th century. In his early twenties, Modigliani moved to Paris, where he became a part of the vibrant artistic community in Montmartre and Montparnasse. His artistic style was influenced by various sources, including African and Oceanic art, as well as the works of artists such as Paul Cézanne and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

The scrap of paper people seemed determined to acquire was a note he wrote in his sketchbook when he was just 23; it provides insight into his creative intentions. In this note, he stated, “Ce que je cherche ce n’est pas le réel par l’ireel non plus, mais l’Inconscient le mystère de l’Instinctivité de la Race,” which translates to, “What I am searching for is not the real nor the unreal, but the unconscious, the mystery of the instinctiveness of the race.” In other words, Modigliani wasn’t interested in painting what you could find in your neighbor’s garden or your local grocery store. No, he had his sights set on the profound mysteries of the human experience.

Modigliani’s note was auctioned at Sotheby’s Paris on October 23rd as part of an Impressionist and Modern Art sale. It came from the same collection as some of the other lots, including 21 Modigliani sketches. Although all the sketches found buyers, they were still far from the price achieved for the note. Initially estimated to be worth a modest €300 to €500, it ultimately sold for an astounding €120,000 (or €152,400 with fees), attracting the attention of collectors willing to pay a substantial sum for this small piece of art history.

____________________

The Dark Side

Munich Museum Thief Sentenced

A German court has sentenced a former museum employee for stealing paintings and then replacing them with forgeries. German privacy laws protect the man’s identity, but the former museum technician was convicted of illegally selling cultural property, for which he received a suspended 21-month sentence along with a €60,000 fine. The anonymous man worked in the archive of the Deutsches Museum, the world’s largest science and technology museum in Munich. However, it also frequently receives donations of art from local collections and organizations. He stole and replaced three paintings between May 2016 and April 2018. All the works were not on display but kept in the museum storerooms, making it easier for him to get away with his theft. He then consigned the originals to the local auction house Ketterer Kunst.

The most valuable of the stolen works was Es war einmal by Franz Stuck, one of Bavaria’s great nineteenth-century painters. With the title meaning Once Upon a Time, the work shows a scene from the Frog Prince fairy tale. It was formerly in the collection of Braunschweig factory owner Arthur von Franquet before being given to the Deutsches Museum after he died in 1931. The anonymous thief also stole Zwei Mädchen beim Holzsammeln im Gebirge (Two Girls Gathering Wood in the Mountains) by Franz Defregger and Die Weinprüfung (Tasting the Wine) by Eduard von Grützner. In total, he received €60,617 for the three works. He also stole a fourth painting, Defregger’s Dirndl, but was unsuccessful in selling it. The thief told auction house specialists that the paintings were family heirlooms. He used the money he received to pay debts and fund a life of luxury. He reportedly bought himself a new apartment, a Rolls-Royce, and several expensive wristwatches.

Reports of the trial say the defendant expressed remorse. Well, of course, he showed remorse. He got caught. I don’t think he was ridden with guilt when he bought that Rolls-Royce. But of course, this is a massive embarrassment for both Munich’s Deutsches Museum and Ketterer Kunst, probably more so for the latter than the former. Auction houses have reputations to uphold, which they do by doing their due diligence and performing extensive research. They have to ensure everything’s in order and that the seller legally owns the work. That way, scandals like this don’t develop to this extent. As for the Deutsches Museum, it is fortunate that the works were returned to them. Perhaps the British Museum should take notes on how this was handled so they avoid further embarrassment in the future.

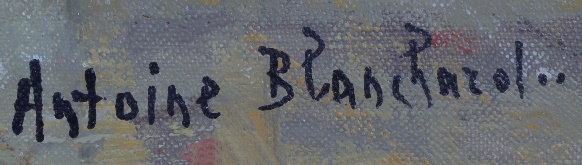

When Will This Stop? Probably Never

Over the years, we’ve written numerous posts addressing the persisting issue of auction rooms and dealers selling fake artworks (included is an image of a fake signature). Unfortunately, this problem shows no signs of abating. Almost every historical artist whose works we buy and sell has had inauthentic works appear on the market. Some of these were mere copies created by other artists aiming to grasp the master’s techniques, while others were produced with the intent to deceive unsuspecting buyers. Shockingly, there have been many cases where the art trade removed an artist’s signature from an authentic work and replaced it with another artist’s name, all in the pursuit of higher profits.

One might wonder why some auction rooms don’t contact experts to obtain informed opinions. The answer, in my view, is simple: they often seem indifferent to the authenticity of the works they sell. They adhere to the age-old principle of “caveat emptor,” meaning “let the buyer beware.”

It’s true that most experts charge for their assessments, but it’s important to recognize the significant investment of time, effort, and energy these individuals have dedicated to comprehensively understanding an artist’s career. Achieving the level of knowledge and discernment that they possess can take decades.

In the realm of art, we are recognized by many as the leading experts for several artists, including Daniel Ridgway Knight, Emile Munier, Julien Dupre, and Antoine Blanchard. Today, I am focusing on the latter artist, Antoine Blanchard (his real name was Marcel Masson).

In the early days, various dealers and auction houses consistently contacted us for our opinion on works attributed to this artist. These actions led us to dive deeper into the oeuvre of Antoine Blanchard and subsequently began creating a comprehensive catalog raisonné, which is accessible at www.antoineblanchard.org. Presently, all research and authentication matters are performed by Amy Rehs. Reputable auction rooms and discerning dealers recognize the value of obtaining an official opinion from her before offering a work for sale, even if a nominal fee is involved. Their confidence in the authenticity of the artworks they present justifies this investment.

However, we also encounter numerous smaller auction rooms and dealers who appear indifferent to this critical issue. Month after month, we observe a disheartening trend of counterfeit paintings being passed off as genuine works. It’s perplexing why this problem persists when there’s a straightforward solution – contacting us for our expertise.

I planned on listing a series of fake works recently sold by several of the smaller auction rooms throughout the US and Canada. After Lance read the post, he suggested I show it to an attorney, which I did. They told me that I could open the gallery to legal action from those firms and even the buyers. So, sadly, my list will need to stay private for now.

Please keep in mind that numerous more fakes are awaiting potential buyers. Ensuring that any prospective art acquisition comes from a source that has done the proper research and diligently verified its authenticity is essential. Additionally, it’s important to remember that, from an expert’s perspective, few things are more disheartening than informing someone that their cherished painting is not genuine.

As I have always said, the art world is a jungle; find the right guide before you become someone’s next meal.

“Unlocated”: Rodin Sculpture Reported Lost

In another incident of a major British museum messing up, the Glasgow Museums have recently admitted that it has misplaced its plaster copy of one of the most famous works by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin. Glasgow Life, which oversees and manages the public museums and galleries in Scotland’s largest city, has added the plaster copy of part of Rodin’s Les Bourgeois de Calais to its roster of 1,750 stolen and missing items. The work, showing one of the six figures portrayed in the original bronze, was displayed by the artist at the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1901. The Glasgow Museums purchased the work and last exhibited it during the Open Air exhibition in Kelvingrove Park between June and September 1949. The museum has said that the sculpture is “unlocated”.

The original sculpture, Les Bourgeois de Calais or The Burghers of Calais, is a bronze statue completed in 1889 by Auguste Rodin. The city of Calais, which sits on the English Channel just over twenty-five miles across the water from Dover, originally commissioned the sculpture in 1884. The work, consisting of six figures standing on a single base, commemorates an episode from the city’s history where a group of Calais’s notables surrendered themselves in exchange for the city being spared from looting and destruction. In 1346, about ten years into the Hundred Years’ War, King Edward III of England laid siege to Calais. After eleven months, the city was in near ruin, so Edward announced that he would leave Calais alone if six local leaders, or burghers, gave themselves up. According to French chroniclers, these men were Eustache de Saint Pierre, Jacques de Wissant, Pierre de Wissant, Jean de Fiennes, Andrieu d’Andres, and Jean d’Aire. King Edward ordered them to appear outside the city walls with nooses around their necks. The six burghers were convinced that the English would execute them should they turn themselves over, yet they complied with the king’s demands. According to the story, Edward’s wife, Queen Philippa, pleaded for their lives to be spared since it would be a bad omen for the child with whom she was pregnant. Rodin’s sculpture of the six men with nooses around their necks has become one of his best-known works. The men appear haggard in simple, ill-fitting sackcloth garments, the effects of the eleven-month siege. They also seem daunted, indicating that Rodin is capturing them when they surrendered to the English rather than when King Edward spared them. The original casting of the sculpture is in Calais, across the road from the city hall. French law dictates that a mold or cast created by Rodin can be used no more than twelve times. Apart from the original, three other castings were made during Rodin’s lifetime, which are now located in the Glyptotek in Copenhagen, the Musée Royale de Mariemont in Belgium, and the Victoria Tower Gardens right next to the Houses of Parliament in London. The other eight casts were created between 1925 and 1995 and are located at museums in Philadelphia, Paris, Basel, Washington, Tokyo, Pasadena, New York City, and Seoul.

According to the Comité Rodin, the Glasgow plaster statue shows one of the six burghers, Jean d’Aire. Jérôme Le Blay, the committee’s director, called the loss “regrettable” but understands that as a plaster work, it’s understandable that museum staff did not give it the care and attention afforded to comparable bronze works. Le Blay and the Comité Rodin estimate the work is worth about €3.5 million, or about $3.7 million.

Lost and Found: More from the British Museum Theft

Yet again, this is another installment in the series of unfortunate events plaguing the British Museum since August. Previously, the museum announced it had fired one of its most senior staff members. This employee, a curator named Peter John Higgs, is suspected of taking advantage of the museum’s lack of transparency and toxic institutional culture of secrecy to steal around two thousand items from the museum store rooms and archives. The museum director resigned earlier than anticipated, and now the administration must deal with the fallout. In this most recent development, the museum seems to be taking a step in the right direction for once. The new interim director, Mark Jones, and the museum chairman George Osborne have stated that the museum will be overhauling its efforts to completely catalogue and digitize their collections.

On the same day the British Museum made this announcement, Jones and Osborne testified before the parliamentary committee on culture, media, and sport. There, they explained how this entire situation came to be and what steps the administration would take to resolve the matter and prevent similar incidents. Jones and Osborne estimate that processing the 2.4 million uncatalogued items and updating the pre-existing entries will take about five years and cost £10 million. But even though the British Museum is owned and operated by the British government, the museum has made it perfectly clear that, given the circumstances, this project will not use any public money. Osborne said, “We are not asking the taxpayer or the Government for the money; we hope to raise it privately”. On top of the cataloging project, the museum plans to change certain rules about archive and storeroom accessibility. Under these new rules, anyone can make an appointment to examine items in museum storage. However, the museum is also planning on tightening its supervision. From now on, researchers, museum staff, or members of the public there by appointment will no longer be able to enter storerooms by themselves.

The British Museum has already recovered about 350 of the estimated 2,000 items stolen. To help, the museum put out an announcement reading, “If you are concerned that you may be, or have been, in possession of items from the British Museum, or if you have any other information that may help us, please contact us at recovery@britishmuseum.org”. It’s a little unnerving that a major cultural institution is resorting to crowdsourcing to find gems and ancient artifacts. But I think it shows how few options the British Museum has left in the wake of the scandal.

Cleveland Museum Sues over Seized Antiquities

The Cleveland Museum of Art is now suing the Manhattan district attorney’s office over confiscating allegedly looted antiquities. Over the past year, the Manhattan DA’s office has been rather busy, looking all over the country for potentially stolen or looted artworks. These artworks are normally either ancient artifacts or more modern art stolen from private collections by the Nazis in the 1930s and 1940s. The Cleveland Museum received a visit from New York investigators in late August, where they seized one of the centerpieces of the museum’s Greco-Roman antiquities collection: a large bronze Roman statue believed to represent the emperor Marcus Aurelius.

The Marcus Aurelius bronze is part of a group of Roman statues looted from the Bubon archaeological site in Turkey soon after its discovery in the 1960s. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art had bronze statues from the same site, that is until April when the Manhattan DA’s office seized these as well. The Cleveland Museum acquired the headless Marcus Aurelius statue in 1986 for $1.85 million (today, it is valued at $20 million). Previously, it belonged to Boston collector Charles Lipson, who very coincidentally bought the statue and three others in 1967, not long after the Bubon site’s discovery. Until the seizure, museum specialists referred to the statue as The Emperor as Philosopher, probably Marcus Aurelius. However, in an attempt to refute claims that this is the same Marcus Aurelius statue looted from the Bubon site, the museum has renamed the statue Draped Male Figure. When news of the seizure first broke, I noticed this, writing, “So, the statue is Marcus Aurelius when it comes to attracting new visitors, but not what it needs to go back where it came from?”

The Cleveland Museum has now sued the district attorney in federal district court in Ohio, saying that the investigators’ evidence was insufficient to warrant a seizure. The museum does not deny that the DA’s office does good work in helping repatriate stolen art and artifacts, but they say that “this is not one of those times”. They dispute the DA’s assertions that the statue came from Turkey and that it depicts Marcus Aurelius. The Cleveland Museum argues that the statue couldn’t possibly be Marcus Aurelius since the subject’s clothing is clearly modeled after a typical Greek philosopher rather than a general, a statesman, or an emperor. However, before this incident, the statue’s dress precisely led specialists to assume that it was a Marcus Aurelius statue in the first place. Marcus Aurelius was not only an admirer of Greek philosophy but a philosopher himself, becoming one of the most prolific figures within Stoicism. His book Meditations is regarded as Stoic philosophy’s quintessential work. This is not speculation; this is what the Cleveland Museum literally wrote for the statue’s description on their website.

The matter is currently before Judge Charles Fleming of the district court of the Northern District of Ohio, who will decide whether or not the Cleveland Museum is the statue’s rightful owner.

____________________

The Art Market

Christie’s London Sam Josefowitz Collection

On Friday, October 13th, Christie’s London hosted a sale featuring selections from the Sam Josefowitz collection. Sam Josefowitz was a Lithuanian immigrant to the United States who, along with his brother David, founded the Concert Hall Society, a mail-order club based in New York that sold classical music records. The brothers ran the company for about ten years before selling to Crowell-Collier Publishing. Josefowitz amassed an art collection known for its diversity, ranging from antiquities to modern masterworks. However, some commentators noticed how he had a special admiration for the painters of Pont-Aven, which included Paul Gauguin, Aristide Maillol, and Félix Vallotton. However, none of these artists were responsible for the top seller that day. That distinction belongs to the Dutch artist Kees van Dongen and his 1918 painting La Quiétude. Van Dongen is often associated with the Fauvists, and one can see why, given his wild and bright color palette. The painting mainly shows two nude women, one completely red, the other entirely blue, lying against a gray background. There’s also a pair of birds, one red and the other blue, observing in the upper left, while a dog and a blue monkey occupy the lower right. Christie’s specialists describe the work as a modernist take on the Orientalist themes of previous generations of painters. The work was only one of two featured in the sale given a £3M to £5M estimate range; the other one being the lot immediately preceding it, Cinq Heures by Félix Vallotton. However, while the Vallotton exactly hit its low estimate, La Quiétude exceeded its estimate range and achieved £9.1M / $11M (or £10.8M / $13.1M w/p). With that hammer Price, La Quiétude is now the second most valuable work by Kees van Dongen ever sold at auction. His 1911 painting Jeune Arabe is the most expensive work, which sold for $12.25M hammer at Sotheby’s New York in October 2009.

After the Van Dongen, next there was a piece by Diego Giacometti. The work is a console table called Hommage á Böcklin, in reference to the Swiss symbolist painter who later came to influence the surrealists and fantasy art. The table is bronze and iron with pieces of copper colored with a green and gray patina. The crossbar contains several trees, while off to the side, near one of the legs, Giacometti placed a small owl figure. Like the Van Dongen, Hommage à Böcklin exceeded its estimate range. Predicted by Christie’s to sell for no more than £3M, the Giacometti sold for £4.2M / $5.1M (or £5.1M / $6.2M w/p). This particular casting of Hommage à Böcklin is now Diego Giacometti‘s third most valuable work sold at auction. A different casting of the work sold at Sotheby’s New York in December 2021 is the sculptor‘s most valuable work, selling for $5.7M hammer. Attesting to the Josefowitz collection’s diversity, the third place lot was one of the several antiquities featured in the sale. This was an Assyrian relief sculpture on a gypsum block dating to the ninth century BCE. At its creation, the Assyrians were the most powerful state in the Middle East. In a display of power and wealth, the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II moved his capital from Ashur to Nimrud, where he built an extravagant palace, the site of which was where the sculpture sold at Christie’s was uncovered. The carving, excavated by Sir Austin Henry Layard and shipped to London by the British consul in Baghdad, shows a character from Assyrian art known as a winged genius. A winged genius is a bearded male figure with bird’s wings and were most often put in places associated with royalty. Estimated to sell for between £2.5M and £4M, the Assyrian winged genius sold for £3.2M / $3.9M (or £3.9M / $4.7M w/p).

Of course, the sale wasn’t without its surprises, the most prominent of which happened to be one of my favorite lots. A version of Albrecht Dürer’s famous rhinoceros woodcut print was up for grabs on Friday, assigned an estimate range of £120K to £180K. Given that it’s one of the German Renaissance master’s most iconic works, I was slightly surprised at such a low valuation. However, it seems a handful of bidders thought the same, fighting over it for several minutes and driving the final price up to £480K / $582.4K (or £604.8K / $733.8K w/p), over 2.5 times the high estimate.

Of the thirty-eight lots available, thirteen sold within their estimates, giving Christie’s specialists a 34% accuracy rate. Only one lot (3%) sold below estimate, while sixteen (42%) sold above. Eight lots failed to sell, giving Christie’s a 79% sell-through rate. With a pre-sale total estimate range of £31.4M and £49.9M, the entire collection fell nicely in the middle, bringing in a total of £42.1M / $51.1M.

Sotheby’s London Modern Discoveries

On Tuesday, October 17th, Sotheby’s London hosted its Modern Discoveries sale, featuring over a hundred works by mainly twentieth-century artists, including Lucien Pissarro, André Brasilier, and Salvador Dalí. The sale started rather poorly, with some portraits by Suzanne Fabry bringing in far less than expected. However, things went swimmingly once the bidders and the auctioneer found their footing. Specialists expected nothing to sell for more than £200K, but those expectations were quickly shattered within the first eleven lots. An early oil landscape by Pablo Picasso quickly got some people’s attention. Created in 1897, when the artist was only sixteen, the landscape is entitled Montaignes près de Malaga and is one of Picasso’s earliest known works. It may not be as abstract as the paintings that made him famous, but it offers a glimpse into the creative mind of a young artist. The work shows a clear influence from the impressionist painting and other avant-garde works that Picasso was exposed to while his family lived in Barcelona for a period of time. Sotheby’s specialists predicted the landscape to be one of the sale’s top lots. And while it certainly did achieve that, I think few were expecting it to go so far beyond its predicted estimate. Expected to sell for no more than £150K, Montaignes près de Malaga eventually sold for £750K / $913.9K (or £952.5K / $1.16M w/p), or five times the high estimate.

Another Picasso work made its way into the top three lots. Obviously, this one comes from far later in his career than the landscape. Like some other works, Picasso gave this one a very specific date for its creation: December 15, 1964. Tête de garçon is a portrait made from crayon, charcoal, and gouache on paper that, though relatively small, was predicted to sell for anywhere between £60K and £80K. The hammer eventually came down at £140K / $170.6K (or £177.8K / $216.6K w/p). With the same hammer price, the painting Sotheby’s specialist predicted to take the top spot ended up coming in third. The untitled oil painting was created by the German artist Rudolf Bauer in 1920. Bauer became associated with the German avant-garde art magazine Der Sturm during the interwar period, featuring work by Franz Marc, Oskar Kokoschka, and Sonia Delaunay. The painting offered at Sotheby’s has a color palette that shows Bauer’s roots in expressionism, yet its abstraction hints at the influence of Bauer’s colleague Wassily Kandinsky.

Eighteen lots, or about 16% of the total, consisted of Picasso’s works. Only three were not ceramics, including the landscape and portrait mentioned above. The third ended up being the other big surprise of the sale. The 7 ¼-by-4 ½-inch piece of paper has drawings on both sides, entitled Tête d’homme barbu and Nu assis de dos. What makes the two even more interesting is that they appear to have been created on two sides of a page removed from a book. On one, a close-up portrait of a bearded man, and on the other, a seated nude from behind, placed underneath the text from whatever book Picasso took the paper from. Thought to sell for no more than £12K, the double-sided Picasso drawing sold for £50K / $60.9K (or £63.5K / $77.4K w/p).

Of the one hundred-eight available lots, forty-three sold within their estimates, giving Sotheby’s specialists a 40% accuracy rate. Twenty-five lots (23%) sold below estimate, while eleven (10%) sold above. In total, twenty-nine lots (27%) failed to sell at all. Against a pre-sale total estimate range of between £2,125,000 and £3,035,000, Sotheby’s Modern Discoveries sale fell in-between at £2,395,000 / $2,918,500.

Jussi Pylkkänen Leaving Christie’s

After thirty-eight years with Christie’s, the auction house’s global president Jussi Pylkkänen (photo courtesy of

Christie’s Images Limited) will step down next year. Even before becoming Christie’s global president in 2014, he was one of the company’s most well-known figures. A native of Finland, Pylkkänen studied art at Oxford University and joined Christie’s in the 1980s as an expert in twentieth-century art. In 1995, Christie’s named him director of its Impressionist and Modern Art department, a position he held for ten years. He served another ten years as president of the company’s Europe, Middle East, and Russia division.

Whenever Pylkkänen was at the Christie’s podium, you knew it was a sale worth watching. He served as auctioneer in selling some of the world’s most valuable paintings, like Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi at a 2017 Post-War & Contemporary sale and Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn at a 20th Century evening sale in 2022. He was also the auctioneer for the sale of some of the most iconic private collections ever to cross the block at Christie’s, including those of Paul Allen, Elizabeth Taylor, and David & Peggy Rockefeller. Pylkkänen will serve as auctioneer for the last time on December 7th at the London Old Masters evening sale. Christie’s CEO Guillaume Cerutti called Pylkkänen “a respected art specialist, a remarkable business getter and one of our best auctioneers.” He is widely credited with helping bring new buyers and sellers to Christie’s, earning its place as the top auction house in the world. He also helped the company achieve its first billion-dollar week in 2015. In the future, Pylkkänen plans on working as an independent consultant and advisor. Though he won’t be leaving the field entirely, his absence will be felt across the art world. His expertise, business acumen, and charm at the podium are what made people want to go to Christie’s.

Sotheby’s London Orientalist Sale

On Tuesday, October 24, Sotheby’s London hosted one of its Orientalist sales, featuring fifty-five paintings by various nineteenth- and twentieth-century European and American artists. For the lots that sold, Sotheby’s experts did a rather good job predicting which paintings would do well once they crossed the block. Expected to be the top lot, Dancers in a Moonlit Palm Grove by Nasreddine Dinet was used by Sotheby’s for the sales promotional material. The work measures 58 ¼-by-46 inches and shows two women in the middle of a dance. The subjects have their arms and faces decorated with tattoos, while the palms of the hands are red with henna dye. This and their jewelry indicate that they are Berbers, the traditionally nomadic people of North Africa, primarily concentrated in Algeria and Morocco. Though not as prolific as other Orientalist artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, Dinet was one of the cornerstones of Orientalist painting in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century France. Unlike other painters who based their works on travels to North Africa, Arabia, the Levant, and Turkey, Dinet completely embedded himself into a community of Berbers in Algeria. By 1903, he spent nine months out of the year in a house he bought in the town of Bou Saâda, about 125 miles southeast of Algiers. By the time he created Dancers in a Moonlit Palm Grove, he had already converted to Islam and changed his name to Nasreddine from his French birth name, Alphonse-Étienne. His popularity among people in both France and Algeria stemmed from his ability to transcend exoticism and focus on detail, almost to the point of his work being anthropology through painting. And the three works offered at Sotheby’s on Tuesday were no exception. Sotheby’s predicted Dancers in a Moonlit Palm Grove to do exceptionally well, with a pre-sale estimate range of £200K to £400K. The Dinet went above and beyond that, with the hammer eventually coming down at £610K / $745.4K (or £774.7K / $946.7K w/p).

Some of the other top lots in the sale were by the French painter Jacques Majorelle. The sale featured four works by Majorelle, most of them typical for the artist since he tended to focus more on Moroccan life than anything else. His oil-on-hardboard painting The Casbah of Anemiter shows a casbah, or fortress, in the Ounila Valley, about fifty miles southeast of Marrakech. The painting is dated 1950, meaning Majorelle had been living in Marrakech for twenty-seven years by the time he created the work. Expected to sell for between £60K and £80K, The Casbah of Anemiter sold for more than double the high estimate at £165K / $201.6K (or £209.6K / $256.1K w/p).

Another painting by Majorelle came in joint third place. Coming across the block immediately after The Casbah of Anemiter, Majorelle created the oil painting Market in Marrakech sometime in the early to mid-1940s. Though he was venturing further south into sub-Saharan West Africa by this point in his career, Majorelle continued creating his Moroccan genre paintings. Sharing third place with the Majorelle was a nineteenth-century painting from the other side of North Africa. Edward Lear’s landscape The Island of Philae, above the First Cataract of the Nile is a bit of a time machine on canvas. Philae was an island in the middle of the Nile near the southern Egyptian city of Aswan. Egyptologists and other scholars focused on it because of its ancient temple (the Sotheby’s sale also featured a closer view of the Philae temple through a painting by Carl Werner that I quite liked). However, in 1958, the Egyptian government began planning the construction of a hydroelectric dam near Aswan, which would cause the Nile, south of the dam, to rise and create a reservoir. Egypt and Sudan asked for help relocating the temples and monuments in this area so they would not be lost underwater forever. Between 1972 and 1979, an international team helped move the Philae temple complex from Philae to Agilkia Island on the other side of the dam. Several other famous archaeological sites were preserved this way, including the temples of Abu Simbel. Both Majorelle’s Market in Marrakech and Lear’s Island of Philae achieved a hammer price of £140K / $171.1K (or £177.8K / $217.3K w/p), with the Majorelle exceeding its £80K high estimate. In comparison, the Lear fell just slightly short of its £150K low estimate.

Other than Majorelle’s Casbah of Anemiter, the only additional surprise of note at Sotheby’s was one of the other paintings by Dinet. Sighting of the Crescent Moon does not show the titular celestial body but rather a crowd gathering on rooftops to spot it. While looking at beautiful natural phenomena is a natural impulse, the crescent moon is an important symbol for the people of North Africa and Muslims in general. In Islam, the holy month of Ramadan starts and ends with the arrival of the crescent moon in the sky, which explains the excitement or awe some of the painting’s subjects are displaying. This particular Dinet painting is rather unassuming, executed with oil paint on a 12-by-10-inch piece of card. Predicted by Sotheby’s specialists to sell for no more than £20K, Sighting of the Crescent Moon sold for exactly double that at £40K / $48.9K (or £50.8K / $62.1K w/p).

Of the fifty-five lots in total, ten of them sold within their estimates, which is about 18%. Nine lots (16%) sold below, while eleven lots (20%) exceeded their estimates. However, it was disappointing to see that twenty-five lots (45%) went unsold, including View of the Bosporus from Üsküdar by François Léon Pieur-Bardin (est. £40K to £60K), And I Will See, Before I Die, the Palms and Temples of the South by Edward Lear (est. £70K to £100K), and The Escort by Rudolf Ernst (est. £80K to £120K). Most of the lots bought in came in the second half of the sale, with sixteen of the last twenty lots failing to meet their reserves. However, partially thanks to the lots that sold over estimate, the sale as a whole actually made more money than expected. All fifty-five lots were predicted to bring in anywhere between £1.45M and £2.3M. The thirty lots that sold made a total of £2.4M / $2.9M.

____________________

Deeper Thoughts

Manet/Degas: The Met’s Look at Modern Masters

On Sunday, September 24th, the Manet/Degas exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened to the public. I arrived twelve minutes after the museum opened, and already there was a line out the door extending nearly to 84th Street. The Met understood that the exhibition would draw large crowds, as many of the over 160 works on display are on loan from the Musée d’Orsay and had never been exhibited outside of France, including Manet’s masterwork Olympia. Knowing this, the Met implemented a virtual queue system to handle the crowds. After scanning a QR code and being told it would only take 15 to 20 minutes, I spent some time perusing the Pre-Raphaelite paintings and Rodin sculptures in the gallery just outside. Other individuals like myself, families with small children, and large groups of tourists from Japan or Italy all joined me. After more than an hour, I was finally allowed in.

The exhibition presents the two artists in the classic compare-and-contrast method, which may seem simplistic but very effective. Even when you first walk in, this is plainly evident. The first thing one sees when entering the exhibition are the faces of the two artists, with a pair of self-portraits standing alone beneath each of their names in large letters (see above). On the left, Manet appears in a yellow jacket while holding a brush in one hand and a palette in the other, as if saying, “Look at me, I’m Édouard Manet and I’m ready to paint!” Meanwhile, on the right, Degas appears all in black with a stern look. He has a pen in his hand but holds it away from the viewer as if guarding the instrument of his work. Instead of an excited introduction, his self-portrait says, “Can’t you see I’m working?” This was a rather fitting introduction to the two men. The exhibition frames these two great artists and their work in the context of their professional and personal relationships. Specifically, they tried to focus on the “creative exchanges that punctuated their careers from the time of the meeting”.

Manet/Degas first highlights the similarities between the two men, both the eldest sons of upper-middle-class French families. They were born two years apart, and they abandoned their legal studies in favor of artistic pursuits. The two first met in the Louvre, where Degas was preparing an etching based on a Velázquez painting. But while the two had many similarities in their background, the exhibition also plainly highlights the dichotomies they represent. Manet was personally more expressive and outgoing, an outspoken Republican who frequently commented on contemporary affairs in his work. The American Civil War, the French intervention in Mexico, the Franco-Prussian war, and the Paris Commune all found their way onto Manet’s canvases at one point or another.

Meanwhile, Degas was reserved and conservative. But while this dichotomy seems very apparent in their personal lives, almost the opposite is seen in their artistic output. Though he seemed more like a free-spirit in his personal life, Manet was more traditional in his professional life. People often associate Manet with the Impressionists, but he never publicly exhibited with them. He maintained his faith in the Salon long after many of his colleagues had abandoned it in favor of independent exhibitions. Manet/Degas implies that Manet and his relationship with the Salon influenced Degas and his artistic aspirations. The exhibition curators suggest that Manet’s Olympia likely overshadowed the large history painting Degas had submitted the same year called Scene of War in the Middle Ages. Therefore, the attention Manet received through Salon works like Olympia may have caused Degas to give up on traditional, more accepted forms of painting altogether.

Of course, just because Manet continued submitting works to the Salon does not mean that his works were at all conventional. Both Degas and Manet pursued their own forms of modernism in different ways. Degas leaned more towards abstraction like his other Impressionist colleagues, while Manet broke from tradition, not through his technique but his choice of subjects. Paintings like Olympia, Déjeuner sur l’herbe, and Dead Christ with Angels may not feature the technical experimentation of his Impressionist colleagues, but the subjects he chose shocked the French public just as much as the technique employed by Degas. This difference is best seen when the two artists chose similar subjects. Several rooms of Manet/Degas show how the two both created work that drew from daily life, from the racetrack to boats on the water, families enjoying their leisure time in the public gardens or at the beach, nights at the opera or in the café.

Scholars have gotten a closer view of Degas and Manet’s relationship thanks to mutual friends, mainly other artists, including Berthe Morisot, her sister Edma, and Henri Fantin-Latour. These artists and their families engaged with each other socially and even intertwined at places. Berthe Morisot married Manet’s younger brother Eugène while at the same time exhibiting with the impressionists alongside Degas. Degas also extended a favor by offering Manet’s stepson Léon a job in his family’s business. Yet, at times, the artists’ relationship became somewhat strained. One example featured early on in the exhibit was the story behind Degas’s 1869 double portrait of Manet and his wife Suzanne, intended as a gift for his friend. Degas shows an intimate domestic scene of Manet reclining on the couch while Suzanne plays the piano. Upset at how his wife was portrayed, Manet cut the canvas in two. Degas took the painting back, repairing it with a piece of blank canvas but ended up not recreating the work entirely. Letters between the Morisot sisters and their mother indicate when the two artists repaired their relationship by mentioning that they were now hosting each other again.

Manet died at 51 due to complications from rheumatism, syphilis, and a gangrene infection. Degas became one of the most prominent figures who spearheaded efforts to help commemorate his life and work. He and Claude Monet petitioned the French government to buy Olympia. He strove to preserve his friend’s memory by acquiring many of his works. Towards the end of his life, Degas owned as many as eighty Manet works, including paintings, drawings, and prints. He even went so far as to recover and reassemble the damaged fragments of one of Manet’s largest, most ambitious works, The Execution of Maximilian, which was on display at the exhibition on loan from London’s National Gallery.

The Manet/Degas exhibition at the Met is not the first time anyone has examined dialogues between artists. Oftentimes, these dialogues occur over great lengths of time and space, like the artistic dialogues between Claude Monet and Joan Mitchell, or between Édouard Manet and Diego Velázquez. But this is one of the first times that these two artists, great friends, and occasional rivals, have been studied together in a curated exhibition setting. Manet/Degas will be running through the first week of January and might be one of the most stimulating and popular museum shows of the year.

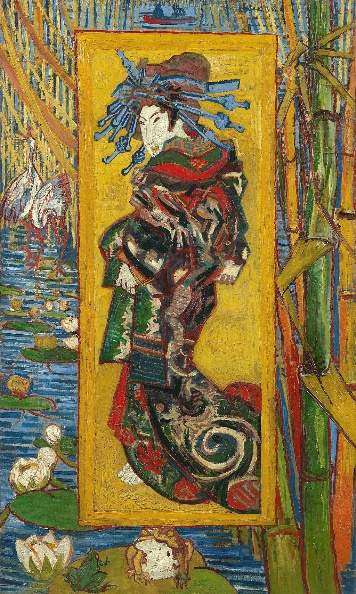

Pokémon Meets Post-Impressionism at the Van Gogh Museum

As part of its fiftieth anniversary, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is teaming up with Pokémon to stage a new series of exhibits. This partnership will bring the creatures from the popular Japanese video game franchise into the vibrant world of the nineteenth-century Dutch painter. Not only is it a fun synthesis of the old and the new, but it also allows people to learn about Van Gogh’s relationship with Japan, particularly how he was influenced by Japanese art.

Vincent van Gogh openly spoke about his interest in and admiration for Japanese art. He first came into contact with Japanese ukiyo-e prints while in Paris. At the time, Japan was starting to open up after nearly two centuries of strict isolationism. Van Gogh fell in love with the colors, the form, and the aesthetics of Japanese ukiyo-e, acquiring several hundred of them and even exhibiting them in the cafés. Many European writers and artists credited Japan’s isolationism as preserving a pure society, untouched by modern problems like disease, overpopulation, and industrialization. Therefore, artists like Van Gogh looked to Japan and its art more or less as a form of escapism or even a panacea for Europe’s ails. Using his collection of ukiyo-e, Van Gogh created many copies and incorporated various elements into his own work. For example, in his 1887 Portrait of Père Tanguy, he shows the art dealer sitting in front of a background of various Japanese works showing landscapes, flowers, and depictions of geishas. These include a depiction of Mount Fuji rising above Tanguy’s head inspired by Utagawa Hiroshige’s Sagami River. Van Gogh even made his own copies of Hiroshige’s work, most notably using the printmaker’s Plum Orchard in Kameido as the basis for Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree. Van Gogh also created his painting The Courtesan, modeled after a print by Keisai Eisen called A Courtesan, Nishiki-e.

The influence Japanese art had on Van Gogh’s work became even more apparent after the painter moved from Paris to Provence. Some artist historians and commentators even suggest that this move to southern France may have been because of his interest in Japan, specifically his desire to leave the urban metropolis behind him in favor of nature, farmland, and greater creative independence. In a letter to his brother Theo sent not long after relocating to Arles, Van Gogh wrote, “My dear brother, you know, I feel I’m in Japan”. While living and working in Arles and Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh Drew likely upon Japanese woodblock prints to create some of his most iconic works. Ukiyo-e‘s aesthetic began creeping into his paintings such as Almond Blossom. Such influence also appeared in his portraiture. In some of his works, like L’Arlésienne, Portrait of Joseph Roulin, and his many sunflower still-lifes, the subject appearing against a solid yellow-gold background seems inspired by Japanese screen painting. In letters to his brother Theo, Van Gogh mentions his appreciation for the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai. He specifically describes The Great Wave Off Kanagawa: “Hokusai makes you cry out the same thing – but in his case with his lines, his drawing, […] these waves are claws, the boat is caught in them, you can feel it.” Some have suggested that the dynamism of the great wave may have inspired the great swirling pattern in the sky and stars in his masterwork Starry Night.

Vincent van Gogh’s Japanese influences have previously been the focus of a Van Gogh Museum exhibition. However, this new collaboration with Pokémon seems less academic and more whimsical. The combination of Van Gogh’s work with Pokémon characters sees Snorlax and Munchlax passing the time in The Bedroom in Arles, Sunflora smiling among a sunflower still life, and Pikachu posing for a portrait in Van Gogh’s gray felt hat. Museum staff are also offering drawing lessons for younger visitors, teaching how to draw Pikachu.

However, not everything has been sunshine and rainbow cards. The museum was completely overwhelmed when the Pokémon exhibition first opened, but not everyone in the crowds was there to peruse the galleries. Many were there to go straight to the museum gift shop. Scalpers buying up the limited edition merchandise to sell out the back has become a serious problem for the museum and Pokémon. Both organizations issued statements, calling these visitors’ behavior “disappointing” and “regrettable”. Even the Pokémon online store got slammed, with Van Gogh merchandise selling out after a day or two. Some have criticized the museum and Pokémon’s lack of foresight regarding the merchandise’s popularity as a “disaster”.

Ukrainian Soldiers Recreate Repin

The arts have assumed a prominent role in the Russian invasion of Ukraine. All over the world, the conflict has caused both individuals and institutions to recognize and help remedy some of the effects of Russian cultural hegemony over Eastern Europe. In one such change, several artists featured in the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art had their official museum biographies changed to show that they were, in fact, Ukrainian rather than Russian. One such artist was Ilya Repin, one of the greatest painters in the nineteenth century in the Russian Empire. And now, one photographer has recreated one of his most famous paintings, bringing his work into the present day.

The Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks is Repin’s take on a semi-legendary incident from the late seventeenth century. According to stories, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were one of the most prominent Cossack hosts in Eastern Europe, living and operating in what is now southern Ukraine for several centuries. In the Ottoman Empire’s attempts to gain increasing control over the Black Sea, the Sultan, commonly identified as Mehmed IV, demanded that the Zaporozhians submit to his authority. In response, the Cossacks drafted a letter to the Sultan, filled with vulgar insults and profanities, expressing their intent to resist the Ottoman encroachment on their lands. Depending on the translation, the Cossacks called the Sultan a “brother and companion to the accursed Devil, and Secretary to Lucifer himself”. They also called him “thou great silly oaf of all the world and of the netherworld and, before our God, a blockhead, a swine’s snout, a mare’s ass, and clown of Hades. May the devil take thee!”

While the Ottomans did indeed try to subdue the Cossacks, the correspondence between the Zaporozhians and the Ottomans is most likely a later fabrication. Regardless, Repin shows the moment when the Cossacks draft their letter, laughing and taking great pleasure in coming up with whatever insults come to mind. The large painting, measuring 80 by 141 inches, was finished in 1891 after over a decade of work. Not long after its completion, Czar Alexander III purchased the painting. The Russian government has owned the painting ever since, with the work currently on display at the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg. Repin began a second, slightly smaller version, which now belongs to the Kharkiv Art Museum in eastern Ukraine, less than twenty-five miles from the border with Russia. The second version is only mostly finished, but it was Repin’s attempt at depicting the Cossacks in a slightly more authentic and historically accurate way.

The Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks is one of the most well-known paintings showing an episode from Ukrainian history by one of the most famous and influential Ukrainian-born artists. Yet the fact that the Russian government owns this painting has not gone unnoticed, especially recently. Keeping that in mind, the French artist Emeric Lhuisset has attempted to reclaim the painting for Ukraine. Lhuisset is primarily a photographer whose work has been exhibited across Europe. In his photograph From far away, I hear the Cossacks’ reply, Lhuisset gathered about forty Ukrainian soldiers, primarily from the 112th Territorial Defense Brigade, to re-create Repin’s painting. Though a modern re-creation, Lhuisset’s work contains many connections to the original painting, the scene it’s depicting, and the current conflict. In both the original and re-creation, we see Ukrainians resisting invasion. The fact that the re-creation features actual Ukrainian soldiers means that not only are they the heirs to the resistant spirit of the Cossacks in the painting, but some might be the literal descendants of such Cossacks. Many see the Cossacks, the Zaporozhains in particular, as one of the progenitors of Ukraine’s national heritage. They are one of the many examples of Ukraine’s status as an underdog resisting much larger forces. Even today, Repin’s image is popular and recognizable enough that even before the 2022 invasion, the internet was full of re-creations in response to Russian aggression against Ukraine. Members of Ukraine’s parliament re-created the image just less than a year before Russia’s invasion as a response to an article Putin wrote about Ukraine. As Lhuisset astutely remarked in his Instagram post, “Culture is a weapon in a vast battlefield, let’s try not to forget it.”

On-Again-Off-Again: Reattributing the Princeton Rubens

Humans are far from perfect, so the decisions we sometimes make aren’t as set in stone as we think. And the Princeton University Art Museum found this out recently. Its curators attributed a small oil-on-panel work to the Flemish Old Master painter Peter Paul Rubens, even though the museum had already stripped the work of such an attribution close to thirty years ago.

The Death of Adonis is a small oil sketch showing a wild boar attacking the titular Greek mythological figure. The story goes that Adonis bled to death in the arms of his lover Aphrodite, whose tears combined with his blood, causing anemone flowers to sprout wherever they dropped. The work is dated to 1639 and is not the first time Rubens depicted the mythic scene. His most famous take on the story came in 1614, with a large oil painting now kept by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The Princeton Museum acquired the oil sketch in 1930 when one of the curators purchased it from Charles Sackville-West, an English baron whose sister Vita was an author and paramour to Virginia Woolf. The museum initially attributed the work to Rubens partially based on its inclusion in an inventory compiled by Rubens’s chief assistant, Jan Wildens. Hermann Gluck of the National Museum in Vienna also aided Princeton curators in their attribution.

The oil sketch lost its Rubens attribution sometime in the 1990s and has since been labeled as “formerly attributed to Peter Paul Rubens”. However, curator Ronni Baer and chief conservator Bart Devolder decided to revisit the subject while restoring the panel in 2019. Skepticism regarding the positive Rubens attribution likely stems from the 1947 article “Rubens in America” by the art historian Julius Held and the writer Jan-Albert Goris. They believed that Death of Adonis is a copy of an original by Rubens since it lacks “the rhythmic force of the master”. However, Held was known to have changed his mind several times about the work. In 1980, Held wrote in a Princeton catalogue on Rubens’s oil sketches, “Contrary to my previously published opinion, I am not convinced that the Princeton sketch is the original one.”

Attributing a work to Rubens is a notoriously difficult task. Like some other Old Masters, Rubens rarely signed any of his works. He also employed any number of assistants and apprentices in his studio at a time. This means that Rubens was far from the only one with a hand in his final works. Furthermore, one of the defining catalogue raisonnés of his work is the Corpus Rubenianum, compiled by the German art historian Ludwig Burchard, which catalogues over 1,100 works by Rubens across twenty-six volumes. However, following his death in 1960, the truth came out that Burchard had exchanged attributions for cash for around sixty works, including the infamous Samson & Delilah at the National Gallery in London, which is considered a fake or a copy by some. Regardless, thanks to revisions made by other art historians, the Corpus Rubenianum is still considered one of the top works in the field of Rubens’ scholarship. However, scholars today are always wary of the risks of using the Burchard catalogue as a source.

Though there has been no official announcement, the Princeton University Art Museum recently changed Death of Adonis’s authorship to Rubens on its online catalogue. With ongoing renovations, the Princeton Museum plans to reopen with the Rubens on display by 2025.

Upside-Down Anniversary

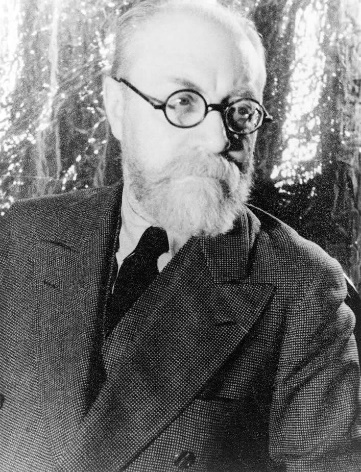

Last November, the State Collection of North Rhine-Westphalia in the German city of Düsseldorf received attention after it came to light that a work by the Dutch modernist Piet Mondrian had been hanging in their galleries upside-down for several decades. However, this is far from the first time someone has accidentally hung a work upside-down. In 1961, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened a new exhibition, The Last Works of Matisse, which included Le Bateau. This was a paper-cut design painted with gouache, a simple depiction of a boat on the water with its reflection mirrored below it. The work was created in 1953, making it one of the last works Matisse ever created before he died in 1954.

MoMA opened the show on October 18, 1961. But forty-seven days later, a museum visitor named Genevieve Habert walked through the galleries and came upon Le Bateau. However, she noticed something rather strange. Both the boat and the purple outline of the clouds seemed more complex on the bottom than on top, which Habert deduced was very uncharacteristic of Matisse. After three visits to the exhibition and getting her hands on the show’s catalogue, she concluded that the work must have been hung upside-down by mistake. This had gone completely unnoticed by museum staff and the hundred thousand people who had visited the exhibition in those six weeks. Habert notified an attendant, who then went to the museum director, Monroe Wheeler. The Matisse was quickly and quietly taken down and rehung the right way around. However, that didn’t stop The New York Times from getting a hold of the story. According to interviews, a museum employee accidentally hung it upside-down because the label affixed to the back of the work was applied upside down. It is not known whether this means the work had been exhibited upside-down previously.

For another example, in 1965, London’s National Gallery accidentally hung Van Gogh’s Long Grass with Butterflies upside-down. A visiting schoolgirl pointed this out about fifteen minutes after staff returned the painting to the gallery wall after removing it for photography. In 1994, London’s Hayward Gallery unintentionally hung Salvador Dalí’s 1928 oil painting Four Fishermen’s Wives of Cadaqués upside-down while on loan from the Reina Sofía Museum. Writers for The Art Newspaper noticed this because of a phallic shape featured on the canvas. “Dalí would hardly have made it point downwards,” wrote Martin Bailey. In 1986, the University of Minnesota Art Museum embarrassingly admitted that one of its most treasured paintings, Georgia O’Keeffe’s Oriental Poppies, had been on the gallery walls hanging vertically instead of horizontally, as intended, for nearly thirty years.

However, some works are actually displayed upside-down rather intentionally. This could be because of an optical illusion, like the works of Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Or, perhaps, it is to make a statement. For example, the portrait of King Philip V of Spain by Josep Amorós is on display at the Almodí Museum in Xàtiva, a town in Valencia. Now, Philip V does not exactly have the best reputation in the town. During the War of Spanish Succession (1701 – 1715), the king laid siege to the town and nearly burned it to the ground. Therefore, the king’s portrait is on display at the museum but is intentionally hung upside-down as a small act of petty vengeance.

The Rehs Family

© Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York – November 2023