COMMENTS ON THE ART MARKET

Gallery Exhibition

Artist Spotlight: Ben Bauer

Rehs Contemporary is thrilled to announce a solo exhibition featuring over a dozen captivating artworks by esteemed American Landscape artist, Ben Bauer. The exhibition will grace the gallery walls through March 1st, offering art enthusiasts the opportunity to immerse themselves in the breathtaking landscapes of the Midwest.

Guided by the enchanting allure of moonlit landscapes and vibrant portrayals of farm life, each piece by Ben Bauer unfolds a tale infused with authenticity and a profound connection to the natural world. The exhibition invites viewers to take a closer look at the artist's skill, exploring the interplay of color, emotion, and intricate details that define his unmistakable and distinctive style.

Additionally, the gallery has conducted an interview with Ben Bauer, providing the audience with a deeper understanding of the artist, his background, and the narratives embedded within his artworks. You can read the interview HERE.

Rehs Contemporary invites art lovers, collectors, and enthusiasts to join them in celebrating the talent of Ben Bauer. The exhibition promises an immersive experience, allowing visitors to explore the nuances of each painting and gain insight into the artist's profound connection with the landscapes he brings to life on canvas.

____________________

Upcoming Art Fair

Our gallery will, once again, be exhibiting at The Palm Beach Show. This year, we will be showing a wide range of works from the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. Featured artists will include Gabriel Alix, Ben Bauer, Stefano Bolcato, Bernard Buffet, Jon Burns, James E. Buttersworth, Todd Casey, Edouard Cortès, Montague Dawson, Gail Descoeurs, Stuart Dunkel, Peter Ellenshaw, Emile Gruppe, Hammond, Lucia Heffernan, Constantin Kluge, Daniel Ridgway Knight, Shana Levenson, Leo Mancini-Hresko, Andrew Orr, David Palumbo, Ken Salaz, Tony South, John Stobart, June Stratton, Mitsuru Watanabe, Anne-Marie Zanetti, and many more (details are below):

Palm Beach County Convention Center

650 Okeechobee Blvd, West Palm Beach, FL 33401

Opening Night Preview

Thursday, February 15, 2024, 5pm – 10pm

VIP Preview: 5 pm entry

Collectors Preview: 7pm entry

General Show Hours:

Friday, February 16 - Tuesday, February 20, 11am – 6pm

If you are interested in attending, please let us know as soon as possible since we only receive a limited number of complimentary tickets. Be sure to note your preference - Opening Night (5PM or 7PM) or General Admission. ticket availability is on a first come, first served basis. Send an email to info@rehs.com

____________________

Stocks & Crypto

The stock market has actually gotten off to a nice start this year… all three major US indexes are up. And while the rally continued through most of the month, the Fed announcement on the final day of January shocked the system a bit. As expected, rates are being held steady… but it was also indicated that a March rate cut was not likely. That was enough to send the markets into a tizzy – in fact, the Nasdaq ended up with its largest single-day decline in more than a year! Even with the last-minute dip, the Dow was up about 1.1% this month, the Nasdaq was up 1%, and the S&P was up 1.6%... nothing too noteworthy, but it’s better than a loss. Some of the top performers included Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), with a gain of more than 27%, and tech darling NVIDIA (NVDA), with a gain of more than 26%... the latter has exploded in the last 5 years, turning in a whopping 1,500% gain over that period.

As for currencies and commodities… the British Pound remained relatively stable in relation to the US dollar, whereas the Euro weakened about 2%. Gold experienced some mild volatility; at one point it was down nearly 3%, but a late rally landed it just about even for the month. Crude set the pace, with futures up nearly 6% through January; oil prices will inevitably be unstable this year as the conflict in the Middle East continues to escalate.

There were big waves in the crypto world… the SEC approved bitcoin ETFs. Initially, bitcoin popped into the high 40K region but has since settled down and even given back a bit. It was down 3.5% for January, but nevertheless, the introduction of bitcoin ETFs marks a profound moment for cryptocurrency as it takes another step toward broad acceptance. Ethereum and Litecoin were in the same boat with marked volatility… Ethereum finished down about 3%, while Litecoin was down more than 10%.

All that said, there’s not a whole lot to complain about so far… things are feeling pretty stable, and while inflation remains elevated, it has certainly settled down. Keep in mind that this is an election year, so you’ll inevitably get your chaos if that’s your thing. Stay tuned.

____________________

Really!?

A Magical Tutu

Recently, the spotlight shone on the three-tiered white tutu worn by Sarah Jessica Parker's iconic Sex and the City character, Carrie Bradshaw, in the show's opening credits. This legendary piece of fashion history went under the hammer at a recent auction, fetching a staggering price that surpassed expectations.

The "oyster white tulle three-tier tutu skirt with a matching satin waistband" became synonymous with the character's exquisite and eccentric style. This particular tutu was one of the five originals used in the show's opening credits, and it's worth noting that Sarah Jessica Parker still owns one of them. With a keen eye for fashion, costume designer Patricia Field discovered and purchased the tutu for a mere five dollars from a bin in Manhattan's garment district.

Parker's character was initially intended to wear a spring 1998 Marc Jacobs runway dress. However, Patricia Field opted for a look that defied the fashion trends of the time, ultimately leading to the iconic tutu's debut.

Not only was the tutu featured in the TV series, but it also made a special appearance in the Sex and the City movie. In a memorable scene, Carrie cleans out her closet, putting on a fashion show of her past New York City looks for her friends—Samantha, Charlotte, and Miranda. The tutu's fate was unanimously decided as a "keep" by the judges.

And so, the recent auction added another chapter to the tutu's storied history, as it sold for an impressive $52,000, well above the estimated range of $8,000 to $12,000. This remarkable price only solidifies the tutu's legacy as a symbol of Carrie Bradshaw's fearless style and the magic of Sex and the City, continuing to captivate fashion enthusiasts around the world.

Alexander Hamilton’s Pistols

Alexander Hamilton’s pistols

Once part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection, Alexander Hamilton‘s pocket pistols recently made waves crossing the auction block. The winning bid reached a substantial $650K ($819K w/p). Christie’s listed the estimate as by request, but reports have stated that the pistols were valued at around $500k. Although these weren’t the pistols used in Hamilton’s famous duel with Aaron Burr, they have their own tale.

The pistols, engraved with Hamilton’s initials “A.H.” and crafted by French artisans Jean-Louis Jalabert and Marie-Anne Lamotte, date back to the period between July 1798 and Hamilton’s death in July 1804.

It’s worth noting that these pistols were not the ones involved in Hamilton’s fatal duel with Aaron Burr. That particular pair was sold in 1930 to the Chase Manhattan Bank, now part of JP Morgan Chase. After Hamilton’s passing, the pistols remained in the family until his great-great-grandson, Schuyler Van Cortlandt Hamilton, sold them to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1950.

____________________

The Dark Side

Theft By Chinese Companies

Stuart Dunkel painting and unauthorized use

of the image by Bellenini

I know this issue has existed for a long time, but it is crucial for galleries, artists, hosting sites, the press, and others to elevate their awareness and commitment to combat the persistent problem of image theft, particularly by Chinese companies.

A recent instance brought to our attention involves a Chinese company named Bellenini (https://bellenini.com/collections/%F0%9F%90%ADmouse-hamster), which has brazenly utilized images by Stuart Dunkel to create numerous products, including t-shirts and sweaters. Upon visiting their site, we were astonished to find dozens of such unauthorized reproductions. Furthermore, the works of many other artists, including Lucia Heffernan, whom we represent, were also being exploited without permission.

Bellenini’s website prompted us to contact Shopify, their hosting site, for the removal of the images. To our dismay, the response from Bellenini, forwarded to us by Shopify, cited a counter notice under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), allowing the reposting of removed content unless legal action is pursued. The exact terminology is below:

In accordance with Shopify’s Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) policy, the removed content listed in the counter notice may be reposted, within ten (10) to fourteen (14) business days following receipt of the counter notice, unless Shopify first receives notice from you that you have filed an action seeking a court order to restrain the Merchant from engaging in infringing activity, pursuant to section 512(g)(2)(c) of the U.S. Copyright Act.

Stuart Dunkel’s painting

and Bellenini’s unauthorized use.

The insistence that artists or their representatives need to hire an attorney to address copyright infringement is absurd, especially when clear evidence and statements deny authorization to the offending company. Hosting sites like Shopify should demand proof of authorization from the infringing party, especially when undeniable evidence establishes the artist’s ownership of the images. In our case, we provided links to the works on our website and included photographs from a recent solo exhibition.

I will add that as of today, most of the items are still not active; however, there are still several that are and we contacted Shopify again about those.

Adding to our concern is the discovery of another site, Lorealwear, utilizing the same images (https://lorealwear.com/search?type=product%2Carticle%2Cpage&q=animal). Given the striking similarities between the two sites, we suspect both are owned by the same individuals in China.

What is even more disheartening is the apparent indifference of the art world press to this issue. Despite reaching out to over 100 press contacts, only two responded, revealing a disconcerting lack of interest in protecting artists. It is interesting to note that some art world news organizations did seem to care when similar accusations were launched at the Chinese fast fashion company Shein (https://rehs.com/eng/2022/04/shame-on-shein/). However, this is likely only because Shein has name recognition, and therefore labor violations and intellectual property theft on their part can catch people’s attention (https://rehs.com/eng/2023/07/the-new-shein-lawsuit/). Bellenini and Lorealwear, though? Never heard of them, so why should we care?

This neglect is particularly dismaying when you realize that press jobs in the art world only exist because of the creativity and efforts of artists. In fact, without artists, there would be no art world. Urgent attention and action are needed to rectify these deficiencies in safeguarding artists’ rights

Sgarbi’s Torch: Unfolding Scandal In Italy

Allegedly The Capture of Saint Peter

by Rutilio di Lorenzo Manetti

Vittorio Sgarbi is a name that I have mentioned in articles several times before. He is a writer, art critic, and politician who, since November 2022, has served as one of the three undersecretaries for Italy’s Ministry of Culture. Given his position and outspoken nature, the foreign press often cites him whenever an incident that grabs people’s attention comes up. I have used his words when discussing Silvio Berlusconi’s art collection and attributing a lost painting to Raphael. However, he seems to be at the center of an unfolding scandal, the details of which have remained mainly in Italian publications. The scandal some call the Manetti Case seems straight from a decently written detective story involving a heist, a shady politician, and an attempt at a coverup, all centered around a seventeenth-century painting. But, to start with somewhat of a cliché, it all begins in an old castle.

Buriasco is a small town just outside of Turin in the far northwest of Italy. The town’s old castle, dating back to the early fourteenth century, is owned by Margherita Buzio, who rents it out as an event space. In February 2013, I imagine on a dark and stormy night, she noticed that one of the castle’s paintings was missing. Someone had cut it from its frame and replaced it with a reproduction. “It was too heavy to take it away like that, and they cut it, replacing it like they thought I wouldn’t notice,” Buzio told journalists. Buzio reported the incident to the Carabinieri, and the painting later appeared on Interpol’s stolen art database. They listed the work as The Judgment of Saint Paul, likely by a student of the southern Italian Baroque painter Francesco Solimena.

While stolen paintings often take years to track down, this one didn’t take long. Later that same year, around May, an incredibly similar painting popped up in Brescia in the hands of conservator Gianfranco Mingardi. According to journalists, Sgarbi told Mingardi he had a painting that needed some touching up. He claimed that his organization, the Cavallini Sgarbi Foundation, was the owner. Mingardi said the painting arrived “rolled up like a carpet.” He photographed the work and performed restoration until he returned it to Sgarbi in December 2018. Mingardi claimed that, given the circumstances, he suspected that the painting was, in his words, “hot”. He asked Sgarbi for documentation on the painting to prove he legally owned it, which Sgarbi could not produce.

Most recently, this painting was exhibited between December 2021 and October 2022 at the Cavallerizza, an old mansion used for art shows in the city of Lucca. It was part of an exhibition called I pittori della luce, or Painters of Light, which included works by Michelangelo da Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, and Orazio Gentileschi. Sgarbi himself curated this exhibition and wrote the catalogue. In the notes, he refers to the painting as The Capture of Saint Peter, created in the mid- to late 1630s by the Sienese master Rutilio di Lorenzo Manetti. This was when some realized that Sgarbi’s painting bore a strange resemblance to a certain painting stolen from a castle near Turin eight years earlier. Sgarbi disputes that the painting ever came from that castle. He claims he found the painting in the attic of a villa his foundation had bought near Viterbo. According to the exhibition catalogue Sgarbi wrote, the painting is mentioned in an inventory compiled in 1649 listing the assets of Andrea Maidalchini, whose sister Olimpia previously owned the villa.

Italian journalists began covering the story in mid-December 2023. When confronted, Sgarbi dismissed any claims that his painting was the one stolen from Buriasco Castle, hurling insults and profanities as he went. This seems to be a recurring theme for him. As I read more about Sgarbi, it became apparent that he is known in Italy for being rather outspoken. Once, while serving in the Chamber of Deputies, he got ejected for hurling vulgarities at fellow deputies, with ushers carrying him out of the chamber by his arms and legs. It became clear why he was always ready to issue a comment on cultural matters. It has little to do with his position as a culture ministry official but his temperament as someone who finds it difficult to refrain from commenting on anything.

By December 17th, the investigative television program Report aired an episode on the subject. When Report’s team analyzed the 1649 inventory at the state archives in Viterbo, there was no mention of a painting by Manetti. The villa’s former owner, Luigi Achilli, who sold the property to Sgarbi’s foundation in 2000, insists that the villa was empty then. Forensic tests later showed that Sgarbi’s painting is likely the one stolen from Buriasco Castle. Because the painting was initially cut from its frame, pieces of canvas from the original painting were left behind. One particular scrap of canvas from the Buriasco painting’s bottom right corner that was left behind attached to the stretcher seems to match with a patch of new, repainted canvas inserted during restoration on the Lucca painting. Additionally, the stolen painting measured 247 by 220 centimeters, while the painting exhibited in Lucca measures 233 by 204. While a differently-sized canvas may indicate that it’s a separate painting, the fact that someone cut the Buriasco painting from its frame means that part of the canvas was left behind, attached to the stretcher and hidden behind the frame. If the stolen Buriasco painting were cut and then put on a new stretcher in a new frame, it would be smaller, just like the Lucca painting. This evidence would indicate that Sgarbi may have knowingly bought a stolen painting. However, one key piece of information reveals something possibly more nefarious.

According to Margherita Buzio, Sgarbi visited the castle, dined in its restaurant, and took a look at the painting in question. A man named Paolo Bocedi later offered to buy the painting at least twice, reportedly for €25,000. A few weeks after Bocedi’s offer, Buzio noticed the painting was missing. There is little information about Bocedi besides that he is a businessman from Lombardy and a close friend of Sgarbi. “We are linked by a friendship that has lasted for 25 years,” Bocedi once said in a November 2023 interview. In May 2013, when Sgarbi delivered the rolled-up painting to Mingardi, who was there to help drop off the painting? According to Mingardi, “a friend of Vittorio brought it to me together with a delivery man”. It was Paolo Bocedi accompanying the delivery truck on a motorcycle. Some journalists have taken this connection to mean that Sgarbi was involved indirectly in the initial theft.

The torch in the upper-right

of the Lucca painting

One of the more potentially incriminating pieces of evidence that the Lucca painting offers is an additional feature not part of the painting stolen from the Buriasco Castle. In previous photographs of the painting, including those taken by Mingardi, there was no torch in the background above the judge’s head. However, the painting exhibited in Lucca includes a torch. Of course, it is not uncommon to find multiple versions of the same subject by the same artist. An artist’s popularity and the demand for their works incentivized them to create multiple copies. However, what is confusing is that the paint around the torch does not have the same craquelure as the rest of the painting. The pigment separation is even across the whole canvas but not around the torch. Thomas Mackinson, writing for the Italian newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano, called it “La Candela Fantasma”, or the Ghost Candle. When presented with evidence that his painting may have been previously stolen, Sgarbi quickly cited the candle as evidence that his painting and the Buriasco painting could not possibly be the same work: “They are different, in mine there is a candle, the other is just a copy”. Furthermore, many have commented that it is incredibly rare for two versions of a work by the same artist (or even an original and a copy) to be completely identical in terms of color, light, and the proportion of its figures. This has led many to believe that the torch was added to the painting to throw off investigators and art historians. According to Alessandro Bagnoli, a professor of art history at the University of Siena, the mysterious torch “seems like an addition made specifically to diversify the painting presented at the Lucca exhibition from the one stolen from the Piedmontese castle.” If these accusations are true this, effectively, would be an attempt at laundering stolen art.

Based on what journalists and investigators have learned thus far, it appears that Sgarbi allegedly tried to buy a painting through an acquaintance, Paolo Bocedi. When that failed, the painting was stolen, cut from its frame and replaced with a replica. Later, a nearly identical painting was given to Gianfranco Mingardi for restoration. Suspecting that the painting may have been stolen, Mingardi returned it to Sgarbi in 2018. Sometime between then and the Lucca exhibition in 2021, someone added the mysterious torch, supposedly to throw off suspicions that it is the same painting stolen from Buriasco Castle. This, it seems, is enough evidence that prosecutor Giovanni Fabrizio Narbone announced on January 9th that Sgarbi will now be under investigation for laundering cultural assets.

Spain Can Keep Holocaust Loot, Says US Court

Saint Honoré, apres midi,

effet de pluie

by Camille Pissarro

While there has been significant progress made in the effort to return art stolen by the Nazis either to their countries of origin or the descendants of their former owners, sometimes not everything can go exactly the way you want. The heirs of Lilly Neubauer found this out recently when a California court decided that one of Spain’s major museums can keep a Pissarro painting which some argue should be returned to the family. Neubauer owned Pissarro’s 1897 painting Rue Saint Honoré, apres midi, effet de pluie until the Nazi government forced her to sell it in exchange for visas for her family. She eventually relented and sold the painting for 900 Reichsmarks, or about $360 at the time (slightly under $7,900 today). In 1958, the West German government declared Neubauer was the painting’s rightful owner and granted her a large sum equivalent to about $250,000 today.

Unknown to the family, Rue Saint Honoré was in a private collection in St. Louis between 1952 and 1976. It was then sold to Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, a Swiss art collector with a title from Hungarian nobility whose family had earned a fortune in steel production in Germany. Today, the baron’s collection forms the core of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, one of the three main museums in Madrid alongside the Prado and the Reina Sofía. In 1999, Neubauer’s grandson Claude Cassirer learned that the museum had his family’s painting and in 2001 began petitioning for its return. In 2005, he filed a lawsuit in the district court for the Central District of California under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, given that the Spanish government owns the museum and its contents. That law provides immunity to foreign governments in suits brought in American courts but with several exceptions. One of those exceptions is if the suit involves “property taken in violation of international law.” By 2022, the case went to the United States Supreme Court. The lower courts had decided that the Cassirer family’s lawsuit qualified for this particular exception, and therefore, they could sue the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in American courts. However, there was also the problem of what law to use in this dispute. The laws of Spain, where the painting is located? Or the laws of California, where the lawsuit was filed? The Supreme Court dismissed the lower courts’ findings and returned the case to them for further review.

In a unanimous decision, the judges of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Pasadena decided that Spanish law should apply in this case rather than California law. In his opinion, Judge Carlos Bea wrote, “We conclude that, under the facts of this case, Spain’s governmental interests would be more impaired by the application of California law than would California’s governmental interests be impaired by the application of Spanish law.” Under California law, stolen property had to be returned to its rightful owner regardless of whether or not the current owner knew it was stolen. Under Spanish law, however, an individual or entity may keep a previously stolen work if it was displayed in good faith for at least three years, the requirements for a proper transfer of title. The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum insists that they did their due diligence and had no knowledge that the painting was sold under duress, meaning they had displayed it in good faith. But even though the appellate court agreed that, legally speaking, the museum is allowed to keep the Pissarro painting, in a concurrence, Judge Consuelo Callahan reminded that Spain is a party to the Terezin Declaration on Holocaust Era Assets and Related Issues. Therefore, she urged the museum to hand over the painting voluntarily since they cannot order their compliance.

Stolen Paintings Founf In Belgian Basement

Tête by Pablo Picasso (left)

and L’homme en prière

by Marc Chagall (right)

In 2010, burglars stole a pair of artworks by twentieth-century masters from a private collection in Israel. Fourteen years later, they’ve finally been located almost 2,000 miles away in Belgium. Tête by Pablo Picasso and L’homme en prière by Marc Chagall were worth around $900,000 when they were stolen from the house of the Herzikovich family in Tel Aviv. The perpetrators of the theft took the works and approximately $680,000 worth of jewelry. The Picasso is one of several abstract portraits created on April 10, 1971. It is made from crayon on board and was last on the market in 1992 when it sold at Christie’s New York for $77k w/p — part of an Impressionist & Modern Paintings sale. A similar work, made on the same day with charcoal, crayon, and watercolor on ruled notebook paper, was offered in 2021 at Standford Auctions in Phoenix. With an estimate range of $225k to $275k, the lot passed. The Chagall is very typical for the artist in showing Jewish themes. The painting shows a bearded Jewish man in the midst of prayer, wearing a tallit and tefillin, as seen by the black box on his head.

The stolen paintings’ rediscovery was set in motion when, in 2022, someone notified police in Belgium that a man in Namur was offering to sell the paintings. This man is a 68-year-old luxury watch dealer from Israel known only as Daniel. Last week, authorities searched his residence but could not locate the paintings. Daniel confessed to having the paintings but would not cooperate with police on their recovery. After further investigation, police searched a building in Antwerp that formerly housed an art gallery to which other stolen paintings were connected. Inside, police found both the Picasso and the Chagall packed in wooden boxes. Both were completely untouched, still in their original frames and had not suffered any damage. Daniel has been charged with possessing the stolen paintings, but it is unknown if he was involved in the initial theft. The collection of jewelry has yet to be found.

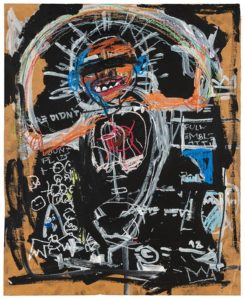

The Orlando Basquiats: OMA Drops Charges

Untitled (Boxer), one of the

Orlando Basquiat forgeries

The situation at the Orlando Museum of Art (OMA) has progressed again. Last time we checked in, disgraced former director Aaron de Groft countersued OMA for wrongful termination, defamation, and breach of contract. This was in response to OMA's lawsuit against De Groft for fraud, breach of fiduciary duty, and conspiracy. Originally, OMA brought its lawsuit against De Groft and the consortium of investors that owns the twenty-five allegedly fake Basquiat paintings at the center of this scandal. However, OMA has dropped its suit against the owners and is now focusing solely on De Groft.

The museum administration decided to focus just on De Groft mainly to cut down on legal costs. Leaked minutes of a museum board meeting reveal that the museum is now facing a deficit of $1 million. So, of course, it’s understandable that they would cut costs wherever they can. The museum’s financial troubles can be linked to the Basquiat scandal. The museum’s chief executive, Cathryn Mattson, explained that OMA has had a 25% increase in unbudgeted expenses, mainly hiring “a legal defense team” and “crisis communication professionals” to help the museum deal with the scandal’s fallout. With the scandal still fresh on everyone’s minds, local donors and philanthropists have proven hesitant or even resistant to help OMA with their financial troubles.

The loss of donors shows that OMA is not only facing a “crisis of liquidity”, but also a “crisis of confidence”. This is partially because the museum administration is keeping everything on such a tight leash. Museum staff who gave statements to the press had to do so anonymously since they had been threatened with termination should they do so. Other museum staff have criticized the museum’s practice of firing or otherwise penalizing any employees who call attention to other forms of “corruption and incompetence” at OMA. Fiorella Escalon, a member of the museum’s Acquisition Trust board, was removed from her position allegedly for voicing her criticism of the current museum board and starting the Save OMA campaign. Escalon’s criticisms call attention to the institutional culture that allowed the Basquiat scandal to unfold in the first place.

OMA has already spent nearly $589,000 on legal expenses and crisis management, earmarking an additional $317,425 in its current budget to pay the hired firms. The museum also anticipates another $500,000 in legal costs for when their suit goes to trial in October 2025. With increased costs and fleeing donors, the museum will find it increasingly difficult to manage other expenses, mainly a new roof and HVAC system estimated to cost $6.8 million.

Here are links to our previous updates on the Orlando Basquiat scandal:

- The initial allegations of the Basquiats being forgeries

- The FBI raid and information about De Groft’s involvement

- De Groft’s dismissal and the case against Michael Barzman

- OMA’s lawsuit against De Groft and the Basquiat’s owners

- De Groft countersues

Cathedral Caper: French Stained Glass in America

from the Seven Sleepers panels

at Rouen Cathedral,

now at the Cloisters, New York

A French cultural organization is trying to force several American museums to return stained glass window panels stolen from Rouen Cathedral. Philippe Machicote is president of the association Lumière sur le Patrimoine, or Spotlight on Heritage, and has actively tried to return stolen French art and artifacts to their country of origin. The organization has recently focused on items taken from France’s well-known cathedrals like Notre Dame and Rouen. Machicote alleges that the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Glencairn Museum in Pennsylvania, and the Worcester Museum in Massachusetts contain stolen stained glass from Rouen Cathedral taken from France over a century ago.

Rouen Cathedral is located in the city of the same name, the capital of Normandy, in northern France. The cathedral is particularly known for its stained glass, with the oldest and most beautiful examples dating to the early thirteenth century located along the nave’s north wall. These windows, in particular, are often known as Les Belles Verrieres. Nineteenth-century restorers removed many of the original stained glass window panels and stored them in the cathedral’s northwest tower. In 1911, the French art historian Jean Lafond inventoried the window panels, finding four missing. Years later, in 1932, Lafond returned and found that someone had smuggled another two out of the tower storeroom.

These missing panels are now in American museums. Most of them come from a single window telling the tale of the Seven Sleepers, a story found in both Christian and Islamic texts. According to the legend, during the third century CE, in the ancient city of Ephesus, now in modern-day Turkey, seven men faced persecution from local authorities due to them being Christian. Rather than renounce their faith, the seven escaped to a cave outside the city. The Roman authorities sealed the cave since it seemed as good as a death sentence. Nearly two hundred years later, a local farmer unsealed the cave and found the seven men still sleeping, believing it had only been a day. They awoke to find themselves in the future, with the Empire having accepted Christianity. Emperor Theodosius II traveled to Ephesus to visit them and hear their story.

Currently, five of the six missing panels are kept by American museums. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has one panel showing the emperor riding into Ephesus to hear the story of the Sleepers. It is now on display at the Cloisters, a museum dedicated to medieval art operated by the Met. The museum’s collection is housed within a French medieval monastery purchased, moved, and rebuilt by the sculptor George Grey Barnard in Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood. The Worcester Museum also has a single panel showing the Sleepers relating their tale to the emperor. Three more panels are held by the Glencairn Museum, an institution for religious art established to house the collection of Raymond Pitcairn. The first of te three shows one of the sleepers going into town to buy food after his awakening, using coins from two centuries earlier. The second shows the curious townspeople bringing the sleeper to the local prefect, to whom he tells his story. The third panel is the odd one out since it is not from the Seven Sleepers story. Despite seven figures in the panel, differences in artistic style lead most art historians to conclude that a different artist made this panel and, therefore, is probably not part of the Seven Sleepers story. The figures are all kneeling together, leading some to call them the Seven Kneelers. Michael Cothren is an art history professor at Swarthmore College and now serves as consultative curator in medieval stained glass at the Glencairn Museum. According to an article he wrote on the windows, the Seven Kneelers are likely a group of apostles. In the original window, the Seven Kneelers would have been displayed next to a scene of John the Evangelist being accepted into heaven by Christ. The Seven Kneelers, according to Cothren, accompany Christ to serve as “an emblematic kneeling apostolic brotherhood”.

However, there is a sixth panel that seems to be missing. The initial four Lafond noted as missing were sold by a French dealer to the American collector Henry Lawrence. When his collection was auctioned off, Raymond Pitcairn bought three of the four panels, while the fourth went to the Worcester Museum, where it remains today. The two that Lafond later discovered missing were bought directly by Pitcairn. One is now at the Cloisters, but the other is unaccounted for. Since it was last in Pitcairn’s collection, it should be at the Glencairn Museum. However, this is unknown since the museum’s collection is not publicly viewable online, and museum officials have not yet answered our questions on this matter.

Machicote and Lumière sur le Patrimoine have filed a criminal complaint with prosecutors in Rouen regarding this matter. They have also recently brought attention to similar cases. In September 2023, the organization recognized that two pieces of stained glass sold at Sotheby’s Paris in 2015 were originally from Notre Dame. The pieces were likely taken from the cathedral in 1862 during Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc’s Notre Dame restorations. However, the prosecutor’s office in Paris refused to take any action. In the case of the Rouen window panels, authorities have approximately two months to decide to proceed with an investigation.

____________________

The Art Market

Velázquez Vanishes From Upcoming Sale

Diego Velázquez

A royal portrait by the Spanish Old Master Diego Velázquez has unexpectedly been withdrawn from the sale of which specialists expected it to be the star. The portrait of Isabel de Borbón is said to be one of the finest works of seventeenth-century Spanish painting to come to auction in decades. It was meant to appear in the February 1st Old Masters sale at Sotheby’s New York. The auction house had guaranteed it for $35 million.

The portrait, created sometime in the 1620s, shows Elisabeth (or Isabel in Spanish), Queen of Spain and wife to King Phillip IV. It is a full-length portrait, measuring just under 7 feet by 4 feet. She was born the eldest daughter of King Henry IV, who established the Bourbon dynasty in France. At 13, she was sent to Spain to marry Philip, who was only 10 years old himself. When they acceded to the throne six years later, they were King and Queen of both Spain and Portugal, which had been joined in a personal union in 1580 under Phillip’s grandfather. The Velázquez portrait, created early on in their reign, was originally held at the Buen Retiro Palace in Madrid, where it likely hung alongside a 1623 Velázquez portrait of the king. It remained there until Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808, and from there, it disappeared until it popped up again in the Louvre several decades later. Over the course of a century, it made its way to Britain and then to the United States. It last sold at auction in 1950 and has been in the same collection since 1978. With a $35 million guarantee, the portrait would have definitely broken Velázquez’s auction record of £8.42 million (or $16.9 million) set in 2007 when Santa Rufina sold at Sotheby’s London.

Since Velázquez was Phillip IV’s court painter, a majority of his work is portraiture of the royal family, its household, and the most important notables of seventeenth-century Spanish society. Therefore, many of his works are held in museums or the Spanish Royal Collection. The portrait of Isabel de Borbón is said to be one of the last major Velázquez works still in private hands. No specific explanation was given as to the painting’s withdrawal other than “ongoing discussions” with the sellers. Some previously speculated that the withdrawal was because an American museum had put in an offer on the painting. However, there is little evidence attesting to this.

Christie's NY 19th Century American Sale

Cattleya Orchid with

Two Brazilian Hummingbirds

by Martin Johnson Heade

On Thursday, January 18th, Christie‘s kicked things off with their first sale of note for 2024. Their 19th Century American & Western sale featured one hundred lots and ended up a good way to start the year. Of course, the star of the sale, the painting everyone expected to shine brightest, was Martin Johnson Heade’s 1871 work Cattleya Orchid with Two Brazilian Hummingbirds. Inspired by contemporary painters and naturalists like Frederic Edwin Church and John James Audubon, Heade frequently made trips to Central and South America as well as the Caribbean to study the flora and fauna there. The painting offered at Christie’s was created after a year of traveling throughout Colombia, Panama, and Jamaica. It also marks one of the first times Heade included both flowers and animals in the same painting. The orchid-hummingbird combination would become a common subject for the artist throughout the 1870s and 1880s. Predicted to sell for between $1.2 million and $1.8 million, the Heade surpassed expectations, with the hammer coming down at $2.8 million (or $3.4 million w/p).

Afterglow, Green River, Wyoming

by Thomas Moran

Next was one of the many landscapes the sale had to offer: Thomas Moran’s 1918 painting Afterglow, Green River, Wyoming. In the hundred years since Moran created the painting, Green River has grown from a rail depot to a small city of 12,000 people. However, the cliffs and other rock formations surrounding the area, with their red and white rock layers as shown in Moran’s painting, can still be seen today as they existed in 1918. Christie’s specialists assigned Afterglow the same $1.2 million to $1.8 million estimate range as the Heade. Though the Moran did not surpass its estimate the way the Heade did, it still hit its high end, reaching $2.2 million w/p. Finally, in third place was the bronze statue The End of the Trail by James Earle Fraser. It was one of the thirteen sculptures featured in the sale. The work shows an indigenous American man on horseback, hunched over with melancholy. Fraser, who had much sympathy for indigenous people, particularly the Sioux, created End of the Trail as a way to symbolize the suffering of indigenous people in the United States. The casting sold on Thursday for $1.1 million (or $1.38 million w/p) against a $500K to $700K estimate. This set Fraser’s all-time auction record. The previous record-holder was a different, slightly smaller casting of the same work, which sold in 2014 for $921K w/p at the Coeur d’Alene Auction House. In fact, different castings of End of the Trail constitute the top five works by Fraser ever sold at auction.

The End of the Trail

by James Earle Fraser

Of course, the sale was not without its surprises. Chief among them was a pair of humorous genre paintings from 1856 by David Gilmour Blythe called Family Prayers and The Sequel. The first shows a family kneeling in prayer before digging into the pie on the table. Seeing a ram just outside the door, a young boy holds his hat in front of the man’s backside to coax the ram into charging. In The Sequel, we see the aftermath. The ram has charged at the man, who is now lying face-down on the floor after falling onto the table, knocking it over and everything on top of it, including the pie. It last sold at Christie’s New York in 2003 for $28K hammer, so the $40K to $60K estimate range was not unreasonable. The pair of paintings achieved over three times the high estimate at $200K (or $252K w/p).

Despite several highly-valued lots being bought in, including A Wagon Train on the Plains by Thomas Worthington Whittredge (est. $300K to $500K) and Along a Greasewood Trail by Ernest Martin Hennings (est. $600K to $800K), in the end, Christies did rather well. Of the one hundred lots available on Thursday, twenty-six sold within their presale estimates, thirty-four sold below, while twenty-four sold above. Sixteen lots went unsold. In terms of total dollar amount, the entire sale fell within its total presale estimate, bringing in $10,546,200 against a minimum of $9,099,000. The Heade painting exceeding its maximum estimate by $1 million likely made up for some of the more valuable lots bought in.

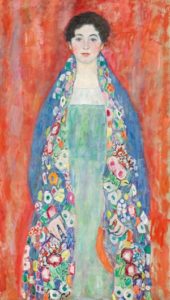

Long-Lost Klimt Up For Auction

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser

by Gustav Klimt

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser is a 1917 painting by Gustav Klimt. Specialists have considered it lost for almost a hundred years. So it certainly came as a surprise when a Vienna auction house announced it would be crossing the block later this year.

The portrait’s subject is unknown, but due to the title, it is likely either Helene or Annie Lieser, the daughters of Justus and Henriette Lieser. One catalogue has also suggested the subject could be Margarethe Lieser, the daughter of Justus’s brother Adolf. The Lieser family was a wealthy Jewish family from Vienna. Klimt left the work unfinished when he passed away in 1918, yet it was still given to the Lieser family. The last known photograph of the painting before its disappearance, taken in 1925, indicates that the family still owned it. After that, the documentary evidence stops. Now that the current owners are selling, we know that their family purchased it in the 1960s. So, the term ‘rediscovered’ might be inappropriate in this case. It’s not like it was chilling out in a basement or laying undisturbed in an archive for a century. It’s been kept in a private collection for over fifty years. But there’s a significant, thirty-five-year gap in the provenance that has left some uneasy since that gap includes the entire Second World War and the Holocaust. Even though the Lieser family endured persecution at the hands of the Nazis, with some of the family members dying in concentration camps and ghettos, there is not much evidence to suggest that the painting was confiscated or sold under duress.

Despite the lack of evidence, however, the parties involved are handling everything with the utmost care and sensitivity. The current owners have consigned the painting jointly with the Lieser family’s descendants to im Kinsky, the second-largest auction house in Austria. In a press statement, the auction house stated that the owners and the Lieser family specifically chose im Kinsky for “their historical knowledge of art and legal expertise,” making it “well positioned to handle these sensitive projects and [take] into account all interests and claims.” Klimt’s portraits, particularly of prominent Viennese women, are rare at auction. Most are held by museum collections, including Portrait of Johanna Staude at Vienna’s Belvedere Gallery, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I at New York’s Neue Galerie, and the Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. The last major Klimt portrait to sell was the well-known Dame mit Fächer, which became the most valuable painting sold in Europe when it brought £85.3 million w/p at Sotheby’s London. Furthermore, many have noted how refreshing the Klimt's sale will be for the art market in Austria. With so many great masterworks getting snatched up with consignments to Christie's or Sotheby's, occasionally Bonhams or Phillips, the art markets in London, New York, and, to an extent, Paris have become perhaps a little oversaturated. So having an Austrian painting by an Austrian artist being sold at an Austrian auction house might give a small jolt of revitalization to the Central European markets.

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser is estimated to sell for between €30 million and €50 million (or between $32.5 million and $54.2 million). Before its sale on April 24th, the painting will go on an exhibition tour, visiting Germany, Switzerland, Britain, and Hong Kong.

___________________

January’s Top Instagram Reels

As many of us are glued to social media, we thought you would enjoy seeing our top posts for the past month. None have hit the level of last year’s #1 post – Cortes’s Champs-Elysees, Arc de Triomphe (which when we announced it was at 163,300 views and 6,600 likes – when something goes viral, it just keeps on going: 591,000 views and 19,257 likes - https://www.instagram.com/reel/C1FdLIHvohW/ )

Rehs Galleries, Inc.

Edouard Léon Cortès’ - Pêche, Normandie – about 15,200 views and 990 likes

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C1nHovCPe3U/

Daniel Ridgway Knight’s – Washerwomen – over 12,800 views and 975 likes

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C2AsuQYPE_8/

Edouard Léon Cortès’ - Place de la Madeleine – over 8,200 views and 510 likes

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C12pKBEPZBJ/

Rehs Contemporary Galleries

New Arrivals – Lucia Heffernan – over 39,700 views and 270 likes

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C2Vp9O0PG6y/

New Arrivals – Stuart Dunkel – over 20,500 views and 280 likes

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C2BeolyshH3/

Ben Bauer – Sleeping Bear Bluff, Moments to Sunup - over 10,600 views and 660 likes

https://www.instagram.com/reel/C2bOd_Xr0NR/

____________________

Deeper Thoughts

Manet’s Asparagus: Humor In The Arts

I took an elective class for my arts requirement when I was at school. It was called Laughter and the Fine Arts and looked into humor and comedy in everything from Aristophanes to Modern Family. People have been making humorous art for millennia, but I feel like when thinking of this, we don’t often consider the modern masters of the last two centuries. Everything for them was very serious, yet they were all as human as anyone and could be silly, playing practical jokes and inserting laughter into their work.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment

Portrait of Fräulein Lieser

by Gustav Klimt

Michelangelo Buonarotti’s work in the Sistine Chapel was incredibly long and arduous. It took the artist four years to complete the ceiling, plus another five years to create the fresco, The Last Judgment, behind the altar. Michelangelo brought the nude human form, the idealized figures of classical sculpture and statuary, into the heart of Western Christianity, which didn’t sit well with everyone. One of the most well-known stories about the Last Judgment‘s creation was when Pope Paul III entered the chapel to view Michelangelo’s progress. This was when the pope’s master of ceremonies, Biagio Martinelli da Cesena, expressed his objections to the amount of nudity in the scene. According to Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Biagio said that “it was a very disgraceful thing to have made in so honorable a place all those nude figures showing their nakedness so shamelessly, and that it was a work not for the chapel of a pope, but for a bagnio [bathhouse] or tavern.” In response to these criticisms, Michelangelo did make one noticeable change. In the bottom right corner of the enormous fresco, we see damned souls being ushered to Hell. Among them is Minos, the judge of the underworld, surrounded by a horde of demons. As his revenge, Michelangelo gave Minos his critic’s likeness. Additionally, he gave him donkey ears while a serpent bites at his genitalia. According to the chronicler Ludovico Domenichi, when Biagio saw this and complained, Pope Paul told him that there was nothing he could do about it since he was responsible for guiding souls to heaven and, therefore, could not do anything about what happens in Hell.

Manet’s Asparagus

A Sprig of Asparagus

by Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet is considered one of the greatest European artists of the nineteenth century for having carved out his own variety of modernism between the Paris Salon and the nascent Impressionist movement. Because of the importance of his work, we often look at it through a rather strict academic lens. However, in some of his paintings, we see touches of lighthearted humanity. This is most apparent in a pair of paintings commissioned by the critic and collector Charles Ephrussi. In 1880, Ephrussi promised Manet 800 francs for a still-life of asparagus. Manet delivered on his commission, giving us Une botte d’asperge, a good-sized look at a bundle of white asparagus with purple tips laying upon a bed of greenery, much like a Paris grocer might display his inventory at the time. Research on the canvas has since revealed that Manet created the work painting wet on wet, meaning that he likely created the whole painting in a single sitting. Ephrussi enjoyed the painting so much that he paid Manet 1,000 francs. Manet was known for being an affable, witty personality in the Paris art scene, so he took the opportunity to make a little joke. Having been paid more than what he was commissioned, Manet went to work and created a separate, smaller asparagus still-life painting. While the original bundle measured 18 by 21 ½ inches, the smaller canvas was only 6 ½ by 8 ½ inches, showing a single stalk of asparagus on a tabletop. When he sent it to Ephrussi, he attached a note reading, “There was one missing from your bundle.” Unfortunately, viewing the two paintings side-by-side isn’t possible right now. While the single stalk is kept at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the original bundle now hangs at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne.

Brueghel’s Flatterers

The Flatterers by

Pieter Brueghel the Younger

Art historians often differentiate Pieter Brueghel the Elder from the Younger by referring to him as the Peasant Brueghel since he gained fame in his own time through depictions of peasant life in the Low Countries. However, it’s not like Brueghel the Younger completely abstained from peasant themes. Some of his most interesting work involves representations of common sayings and proverbs, which sometimes can be confused for simple representations of peasant life. For example, there’s a young man with a knife and some bread, which is sometimes associated with the proverb “The man who cuts wood and meat with the same knife.” He also had his interpretation of the classic “blind leading the blind” allegory. Then, there’s a depiction of a drunk man being forced into a pigsty by the rest of the village, often associated with the popular saying, “The pig must go into the stall.” In translating contemporary morality onto the panel or the canvas, Brueghel the Younger often required a bit of humor, and nowhere is that more apparent than in the painting known as The Flatterers. It shows a large man with a bag of money, pouring the coins out onto the ground while a group of smaller men make their way up his backside. It has a touch of the surreal, but the meaning becomes a parent when you understand the popular proverb it invokes: “Because so much money creeps into my sack, the whole world climbs into my hole.” It’s a rebuke of what we would now call brownnosing. Brueghel even includes a man in a long, brown robe in his crowd of ass-kissers, like that of a Franciscan friar, showing that even the seemingly-lofty among us can fall victim to greed and other vices. Even though the work is meant to convey a serious moral lesson, viewers at the time and even today can’t help but chuckle. There’s a hint of silliness, which I think only enhances the work’s message.

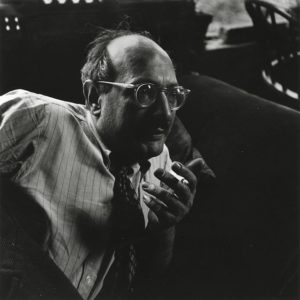

Rothko’s Seagrams Murals

Now for a bit of dark humor… in more than one way, I suppose. In 1958, the Canadian beverage company Seagram was about to move into its new headquarters at 375 Park Avenue in New York. The structure, known as the Seagram Building, was designed primarily by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and is one of the finest examples of the international style of architecture. Seagrams wanted a restaurant in the building, with works by a prominent artist for the interior. They picked Mark Rothko for the job at the recommendation of Alfred H. Barr Jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art. Rothko was well-known then but was only starting to become successful. He was looking for an excuse to create a large series of works experimenting with a darker color palette.

The Seagrams commission would give Rothko that opportunity and a space where he would show them all. He was hesitant, however, because of his dislike of materialist consumption, of which the new Seagram Building and its fancy restaurant would be symbols. He was only meant to make seven large paintings but created thirty, from combinations of red and orange to black and burgundy. After over a year of work, Rothko began to grow tired of the commission, to the point that he felt he was actively creating something intentionally antithetical to the eventual exhibition space. In 1959, he admitted to journalist John Fischer, “I accepted this assignment as a challenge, with strictly malicious intentions. I hope to ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room […]. If the restaurant would refuse to put up my murals, that would be the ultimate compliment.” At least Rothko was able to find a bit of humor in what he was doing. It was almost like a practical joke on big-headed businessmen. However, in 1960, Rothko was invited to dine in the new restaurant, the Four Seasons. It seems that was a breaking point for him, and not long after, he chose to cancel the initial contract. Rothko reclaimed all 30 paintings in the series and returned the money given to him. He later complained to his studio assistant, “Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine”. The Seagram murals, as they came to be known, were locked up in storage. They have since been sold and scattered, with nine being shipped off to the Tate Gallery in 1969.

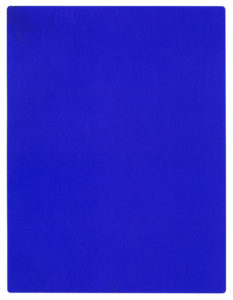

Yves Klein’s Blue Surprise

IKB 191 by Yves Klein

Yves Klein was a French artist in the immediate postwar period. He was foundational in what later became the nouveau réalisme school and was incredibly influential in developing minimalism, pop art, and performance art. However, many people who know his name will associate him not with a specific work but with a color. He developed International Klein Blue (IKB), a deep, dark shade of blue close to ultramarine, which he used extensively in his work. One of his most well-known paintings, IKB 191, is simply a monochrome painting consisting solely of a canvas painted with synthetic resin and then dusted with the paint’s dry pigment. However, there is a select group of people for whom the color is unforgettable because of an incident in April 1958. That month, Klein opened a new exhibition at the Galerie Iris Clert called Specialization of Sensibility from the State of Prime Matter to the State of Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility. This exhibition would later become known as the Void. The gallery’s windows were entirely painted with IKB, while a canopy of the same color was installed over the door. Twenty-five hundred people showed up to the opening. The gallery served the guests blue gin-and-Cointreau cocktails, which they drank before being let in about ten at a time. There, they saw the entire gallery completely cleared out and painted white. That’s it; nothing was on display or hanging from the walls. According to Klein, he had rendered all of his paintings immaterial, which in The Void could allow you to concentrate and get your mind to do all the creative heavy lifting. However, the show wasn’t over yet. When the gallery-goers returned home, they were in for a little surprise. The blue cocktails got their color from methylene blue, a saline solution used as a dye and a medication. Many guests urinated International Klein Blue for up to a week after the show. I’m not sure if it was intentional, but that’s what I call branding.

Cyberattack Hits American Museums

A tech service provider that works closely with many American museums announced it experienced a cyberattack recently. Gallery Systems stated they realized they had a problem on December 28th, when the computers running their systems became encrypted and inoperable. As a result, several major museums that use their program eMuseum could not display their collections online. Another program affected is TMS, which curators use to store and view information ranging from documentation of collection items to lists of donors. The cultural institutions affected include the Rubin Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Cyberattacks against cultural institutions are becoming more and more common. Most notably, there was an incident involving the Metropolitan Opera House’s website, where hackers targeted the site’s ticket-selling abilities. The opera house’s box office was closed for nine days. The Philadelphia Orchestra and the British Library have also faced similar attacks. Many of these incidents involve ransomware, where a hacker or a group of hackers holds a website hostage until the required money is paid. While Gallery Systems has already launched an investigation, hired a third-party cyber security team, and notified law enforcement, the nature of the attack is not yet known. If it is a ransomware attack, no demands have been made public. Larger museums that use Gallery Systems’ technology, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum, used their own databases and were not affected.

According to a Gallery Systems statement, “We have been working around the clock to restore access to the software, and we sincerely appreciate your patience during this time. We will be restoring your data with the last available backup.” Several museums also reassured everyone that the incident had not affected personal data.

Gertrude: Art Through An App

In an age of social media and instantaneous communication, promoting yourself as an artist is easier yet more difficult. Yes, you can get the word out quicker, but so can everyone else, leading to a bit of oversaturation. Therefore, even now, it can be difficult for young, emerging artists, some of them straight out of school, to make not just a name for themselves but a living as professional artists. But there’s an app lending a hand, connecting young arts graduates with potential buyers using an incredibly unassuming name.

In September 2023, the South London gallery The Sunday Painter, run by Harry Beer, Will Jarvis, and Tom Cole, launched Gertrude. According to Jarvis, Gertrude is a “bespoke, professional tool” that helps connect “artists, art industry professionals, and art buyers, new and established, enabling artists to launch, build, and sustain successful careers.” The app is named in honor of Gertrude Stein, the American writer who became known as a major arts patron and for hosting one of the most prolific Paris salons of the early twentieth century. She exhibited and collected the work of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Francis Picabia, among many others. It seems Gertrude (the app) updates the idea of the private salon. It feels like a social media site, with artists curating their respective pages where they can keep followers updated about new works. However, Gertrude is also an e-commerce platform for people to buy art themselves. According to the app’s creators, combining these two formats may help people become more comfortable patronizing their favorite artists. They hope that Gertrude will help bridge what they call “a cultural chasm where people don’t feel they are entitled to an opinion about art.” Having an app associated with a pre-existing gallery like the Sunday Painter provides it with pre-formed infrastructure and relationships. However, Gertrude just got another boost recently.

The New Contemporaries is a British arts organization that, since 1949, has been dedicated to supporting artists at the very beginning of their careers. Artists connected to the New Contemporaries include Anish Kapoor, David Hockney, Antony Gormley, and Damien Hirst. Members of the New Contemporaries seem to have great trust in Gertrude. Currently, 82 artists are using the app, with 55 of them being New Contemporaries exhibiting at the Camden Art Centre starting January 19th. While New Contemporaries exhibitions have often been where young, emerging artists in Britain can attract attention and sell some of their work. Gertrude’s aim is to help this process along. With arts funding getting slashed, particularly in Britain, many artists might need Gertrude now more than ever.

Apps like Gertrude allow buyers to bypass traditional galleries, dealers, and exhibitions, but that does not seem to be the point. According to The Sunday Painter, they plan to collaborate with other London galleries like Seventeen to promote the use of the Gertrude to get new audiences familiar and comfortable with buying art from a brick-and-mortar establishment. If Gertrude is truly new and innovative, then, of course, it deserves some attention. However, with many preexisting sites and apps like Artsy and Saatchi, it might be difficult for Gertrude to get a cut of the action.

The Stylish Style: Why Is Mannerism Weird?

If you go to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, you will see many wonderful things. You might recognize Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes or the portrait of Medusa’s head by Caravaggio. Most people will instantly go towards the major Botticelli works on display, like The Birth of Venus, Primavera, and The Adoration of the Magi (which includes the artist’s self-portrait on the right-hand side). However, few people will be ready for a rather strange painting on display at the Uffizi. It’s a Madonna and Child painting, but there’s something off: the Christ Child has an oddly long torso, with a large head and very pale skin. There is a herd of androgynous figures off to the left side, while a random, standalone column dominates the background. After looking at it for a minute, you then begin to see the weird, elongated features of the Virgin Mary, particularly her long neck. Well, that’s the reason the painting is called Madonna dal Collo Lungo, or Madonna with the Long Neck. And it’s okay to say that the painting is weird. It’s sort of meant to be weird. And that is the main thing you need to understand about Mannerism.

Madonna with the Long Neck

by Parmigianino

Many people’s perception of art history typically involves the idea that the Renaissance brought about a renewed interest in classical art and philosophy, and it was nothing but perfect naturalism from then until the Impressionists. However, in the same way that people today are often very aware of generational differences, prioritizing naturalism in the visual arts has ebbed and flowed over the centuries. At the height of the Renaissance in Italy, between 1480 and 1520, many up-and-coming artists seemed to believe that with so many legendary masters running around, there was nothing truly great for them to do. Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, and Botticelli, as well as earlier masters like Donatello, Paolo Ucello, and Giotto, had all made great artistic innovations and breakthroughs, leaving little for everyone else. Young artists certainly tried to copy and imitate the great masters, but they realized this would not get them anywhere. Vasari, in fact, once attributed a quote to Michelangelo, where he once said, “Anyone who follows others never passes them by, and anyone who does not know how to do good works on his own cannot make good use of works by others.” Of course, he was commenting on imitating the ancient master sculptors. Still, he could have just as easily been commenting on the new generation of artists honing their craft through making studies of the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

But rather than stick to imitation, some of this new generation of artists decided to blaze a new trail. They saw the renewed classical ideals in Raphael’s paintings and Michelangelo’s sculptures and chose to reject them. Plus, with the Protestant Reformation kicking off in 1517, perfection and naturalism no longer reflected their world. Europe was becoming increasingly chaotic, so these artists diverged from naturalism, trying to create something bolder and more stylized. By around 1530, with many of the great Renaissance masters having passed away, these new artists were creating some of the most unique paintings of the day. But this uniqueness meant a complete disregard for anatomical correctness and perspective, which almost always throws off people unfamiliar with the Madonna with the Long Neck.

Created in the 1530s by the painter Francesco Mazzola, known as Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck is the quintessential Mannerist painting. It rejects the Renaissance ideals of anatomical naturalism in several ways. The Christ Child’s torso is far too long, and its head too large. His skin is pallid and gray, almost like that of a corpse. Some art historians have noted his limp left arm and how it resembles Michelangelo’s sculpture Pietà. The Virgin Mary’s body is oddly elongated, with a curving torso, spindly fingers, and long neck possibly serving as an example of the Mannerist figura serpentinata, or the posing and distortion of the body to evoke movement. Furthermore, the androgynous angels on the left show that the Madonna is incredibly tall, nearly twice their size. And finally, the lone column in the background. Among the ideals of the Renaissance was not just beauty and balance but logic. Things had to make sense. A single column not holding up anything, not serving any structural or architectural purpose, makes no sense and would seem out of place in an earlier painting.

Venus, Cupid, Folly & Time

by Bronzino

One of the other hallmarks of Mannerism was the greater inclusion of allegory and symbolism. Parmigianino does this very well in Cupid Making His Bow. The Mannerist distortion of proportion is again on display here, as Cupid’s legs seem far too long and his head too small. He carves his bow from a cherrywood branch while stepping on some books for support, representing the triumph of love over knowledge. Other artists also chose to include such symbolism, including Bronzino. When it comes to masterworks of Mannerism, Madonna with the Long Neck is often uttered in the same breath as Brozino’s Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time. While Bronzino is known mainly as a portraitist, this allegorical painting is often considered one of the great works of Mannerist painting. Cupid kisses his mother, Venus, laying his hands on her in an overtly erotic fashion. Meanwhile, Folly approaches them to shower them in rose petals, accidentally stepping on the rose bush’s thorns. The bald male figure, Time, rushes to hold up a blue sheet to shield the scene from whoever is supposed to be in the background. All the figures have some sort of distortion, whether Cupid’s odd, elongated body and his uncomfortable pose, Time overextending his arm, and Folly, a cherub-like figure contorted into the Mannerist figura serpentinata. While Bronzino’s portraits are often incredibly calm and stoic, that cannot be said for Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time. The lack of background and the figures’ layout makes everything seem chaotic and claustrophobic. Everything is all over the place, with bright colors contrasting, throwing the earlier Renaissance ideals like balance and harmony out the window. Scholars have long debated the meaning of the painting, with some saying it’s about forbidden passion while others claim it’s about syphilis.

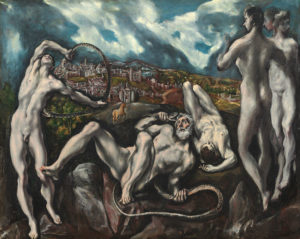

Laocoön by El Greco

The word ‘Mannerism’ derives from the Italian word maniera, meaning ‘manner’ or ‘style’. It is, therefore, sometimes called “the stylish style.” I’m not sure if that’s supposed to be a literal translation, or possibly a euphemism because of its relative strangeness. But sometimes, rejecting a previous generation’s values is a good thing. People have good reason to question why we do things a certain way. And while Parmigianino and Bronzino’s works described above can serve as an example that going out on your own can produce some rocky results, it’s often just because some kinks need to be worked out. In the end, Mannerism did produce many truly marvelous works. One of Parmigianino’s earliest Mannerist experiments is a self-portrait he made at the age of 21, showing him reflected in a convex mirror his barber used; when Mannerism plays with perspective and form without seeming too strange. This is what the later great Mannerist painters did, like El Greco and the lankiness of his portraiture subjects and the stylized poses in his historical and religious works, or Tintoretto and his play on perspective in his Last Supper or use of allegory and symbolism like in Origin of the Milky Way.

Yes, I still think Mannerism is weird. But there’s a certain beauty in its weirdness, which I always have respect for.

PAFA Ends Degree Programs

The Pennsylvania

Academy of the Fine Arts

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia is the oldest art school in the United States. It has trained generations of artists forever over two centuries. And now, after all that time, it will end its degree-granting programs in 2025.

PAFA has an incredible history as an incubator for some of the great American artistic minds ranging from Thomas Eakins, Daniel Ridgway Knight, and Mary Cassatt to David Lynch, Robert Henri, and David Palumbo. The Academy and its museum have a reputation for thinking ahead of the curve. In 1844, PAFA was one of the first major art schools to allow women to study, more than fifty years before other schools like the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris did the same. Furthermore, even before public pressure began mounting for museums to curate more inclusive collections, PAFA’s museum used the $36 million it received after deaccessioning Edward Hopper’s East Wind Over Weehawken to fund the acquisition of works by female and Black artists. But now, the school will end its BFA and MFA programs due to decreasing enrollment and an increasing deficit. However, the school museum will remain open and continue to host educational programs for students in kindergarten through high school. Academy president Eric Pryor said that the decision to end their main programs may have been painful for everyone, but it had to be done. “Just burying our heads in the sand and hoping that things would change I just think wasn’t an option.” The Academy hopes that terminating these degree programs would save the school around $1 million. Meanwhile, renting out some of the school’s buildings can cover the remainder of the $3 million deficit. Anne McCollum, PAFA’s chairwoman, estimates that the school will return to running a surplus by 2028.

Hopefully, ending the BFA and MFA programs will only be temporary. Much of the decline in enrollment started in 2019. Since then, the school has seen about half the number of new students than in previous years. Since this decline is so recent, it can easily be blamed on COVID-19 or the economy rather than a genuine lack of interest in arts education. MFA students, as well as third- and fourth-year BFA students, will be allowed to finish their degrees. However, first- and second-year BFA students must find other places to attend. Thankfully, PAFA is partnering with several schools in eastern Pennsylvania, such as Arcadia University, Temple University, Moore College of Art & Design, and the Pennsylvania College of Art & Design, to help these students transfer into comparable programs.

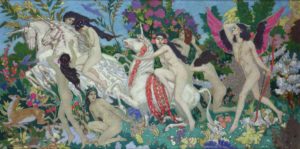

Unicorn: Scottish Museum’s Upcoming Exhibition

Nowadays, when people think of unicorns, they think of them in the context of children, like little kids playing with unicorn dolls or watching My Little Pony. But a museum in the Scottish city of Perth is ready to tell the unicorn’s story more three-dimensionally. The Perth Museum, about an hour’s drive north of Edinburgh, will host an exhibition featuring art, artifacts, and texts to explore the cultural history of the unicorn. It seems appropriate that a Scottish museum would take on this task since it is Scotland’s national animal.

The Perth Museum plans on looking at how humanity has imagined and used the unicorn “from Pliny to Pride”. This fictional animal first appeared in ancient times, with some archaeologists identifying one-horned bovine and equine creatures on Bronze Age Indian decorative pieces. However, the first time a unicorn definitively appears is in ancient Greek texts on natural history. The fifth-century BCE physician Ctesias wrote the book Indica, detailing the flora and fauna of the Indian subcontinent based on Persian sources. In it, he describes a kind of donkey with a single two-foot-long horn. However, ancient Greek texts regarding the animals of far-off places are often not the most trustworthy. In his Histories, Herodotus described India as the home of packs of ants the size of foxes, while dog-headed men live in Libya.

In medieval European art, the unicorn became a common symbol. If you ever go to the Cloisters Museum in upper Manhattan, you will see countless tapestries featuring the fantasy creature. They are typically depicted in captivity or as the target of a hunt, often meant to draw parallels to Christ’s Passion. The parallels continue in that European folklore dictates that virgin women are the only ones who can tame a unicorn. In Scotland, the unicorn was adopted as a royal symbol in the early fifteenth century during the reign of the Scottish king James I. The unicorn became incorporated into the Scottish royal arms and even appeared on Scottish currency in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In 1707, when an act of parliament merged the Kingdoms of England and Scotland to create the Kingdom of Great Britain, the new coat of arms featured a shield with the national symbols of England, Scotland, and Ireland, along with a crowned lion supporting one side and a chained unicorn supporting the other.

The Perth Museum’s exhibition, Unicorn, also plans to show how people tried to bring the fictional animal to life. Several pieces will be on loan from the Victoria & Albert Museum made from narwhal tusk, which, during the Middle Ages and into the early modern period, was often passed off as the horn of the unicorn. Whether carved with a decorative pattern or made into jewelry, these tusks were incredibly valuable, with Queen Elizabeth I paying as much as £4 million in today’s money for a complete tusk. But the exhibition also plans on featuring more modern depictions of unicorns. They have become incorporated into modern fantasy art and literature. On loan from the Dundee Art Gallery, John Duncan’s 1920 painting The Unicorns shows a group of nude female figures fleeing on the titular creatures from a winged male carrying a bow, meant to represent the god of love. Furthermore, the museum curators plan on telling the story of the unicorn as an LGBT symbol. The rainbow is one of the most ubiquitous symbols of LGBT and queer pride, leading the unicorn to become a symbol as well. The rainbow and the unicorn have been inextricably linked for centuries, so the connection is not too difficult to see. Furthermore, the unicorn is also a symbol of magic, elusiveness, and individuality.

Unicorn at the Perth Museum opens on March 30th and will run until September 22nd.

The Rehs Family

© Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York – February 2024