COMMENTS ON THE ART MARKET

Beth Sistrunk

(1978 – 2023)

It is with great sorrow that we announce the passing of beloved artist Beth Ann Sistrunk.

It is with great sorrow that we announce the passing of beloved artist Beth Ann Sistrunk.

Beth was born in Wheeling, West Virginia to Jerry and Beverly Grubb, and was raised in south-east Ohio. Growing up in the rural Midwest, she spent much of her childhood caring for animals and creating everything her imagination desired – from dolls and their clothes, to paintings and drawings, to tiny pet residences and wooden boats. Her summers were a time for exploring the outdoors and feeding her imagination, and during the winters, she would design dream houses, ball gowns, and landscapes on paper… all the while, her cat Boots and her golden retriever Sunney were at her side. As a young woman, she was both kind and gifted… she graduated as valedictorian of her high school, was 1st trumpet in the school band, sang in the school choir, and mastered the piano, all while being an active member of 4H and Girl Scouts.

After working in graphic design and the financial industry through her 20s, she realized she wanted to pursue her first love – painting. She studied everything she could get her hands on, including texts written in the 19th Century, a few of which were in French, and thought about painting all day, every day. She developed a habit of constant analysis and thoughtful execution that helped her become a world-class artist.

Beth has been represented by Rehs Contemporary Galleries in New York City since 2018 and her work has been exhibited in many prestigious galleries and museums across the country. Her work has appeared in countless publications, including American Art Collector, Southwest Art Magazine, Strokes of Genius, and many others.

Images of her paintings can be found on BethSistrunk.com and RehsCGI.com. Beth is survived by her husband Earl, parents Jerry and Beverly, and her brother Alan. She will be deeply missed by her family, friends, and fans of her artwork.

____________________

Stocks & Crypto

By: Lance

It was a bit of a mixed bag for the markets through the month of May… and rightfully so. There are always a myriad of forces putting pressure on stocks, but these days it’s just hard to make sense of what exactly will move the markets – the past few weeks, we’ve been balancing news of a potentially unprecedented US government default and cooling inflation, which might allow the Fed to pause rate hikes. On top of that, stocks tied to Artificial Intelligence are booming, which has fueled a nice run for the NASDAQ. When the markets closed this past Wednesday, May saw a loss of 3.3% for the Dow Jones, a gain of almost 6% for the NASDAQ, while the S&P held nearly even with a gain of just 0.29%. Fortunately, in the final days of the month, House Speaker McCarthy and the President were able to strike a deal to raise the debt ceiling which would avert the first-ever US default on government debt. Though the deal still needs to clear a few last-minute hurdles, it does help relieve some anxiety being felt by investors.

Turning to currencies and commodities… both the Pound and Euro weakened relative to the US Dollar – the Pound was down 0.88%, and the Euro fell a sizable 2.87%. Gold experienced a small dip of 1.3%, while oil got absolutely crushed… it dipped below $70/barrel after a loss of more than 11% for the month. In a similar fashion to stocks, cryptocurrencies were rather mixed for May… Bitcoin slid nearly 5%, Ethereum was up 1.6%, while Litecoin climbed more than 8%.

While there are certainly lingering fears of a recession later in the year, it seems that for the time being, investors are cautiously optimistic about the future. Hopefully, we’re in store for a strong summer!

____________________

Featured Artist Exhibits

This month we have dedicated Gallery 1 and Gallery 2 to

Julie Bell Mark Laguë

____________________

Really!

By: Amy

The Last Emperor's Watch

The last Emperor of China was Aisin Gioro Puyi, also known as Henry Pu Yi. He was born on February 7, 1906, and became the Xuantong Emperor at the age of two in 1908. Talk about starting your career early!

However, Puyi's time as Emperor was short-lived. In 1912, at the tender age of six, the Xinhai Revolution swept across China, resulting in overthrowing the Qing Dynasty and establishing the Republic of China. Puyi abdicated the throne later that year, becoming one of the youngest ex-rulers in history. It's safe to say his retirement plans came earlier than expected!

Despite the end of imperial rule, Puyi continued to reside within the opulent walls of the Forbidden City. During the Japanese occupation of China in the 1930s and 1940s, he became the Emperor of the puppet state of Manchukuo.

Beyond his imperial role, Puyi had a fondness for Western culture and fashion. Even while confined within the grandeur of the Forbidden City, he would often sport Western-style suits and wore a collection of stylish hats and accessories.

Recently, a watch once owned by Puyi made headlines at an auction in Hong Kong. The rare Patek Philippe watch, one of only eight known Patek Philippe Reference 96 Quantieme Lune timepieces, sold for a record HK$49 million ($6.2 million), more than double the $3 million estimate. Puyi gifted it to his Russian interpreter while the Soviet Union imprisoned him. This sale marked the highest result for any wristwatch that once belonged to an emperor.

Recently, a watch once owned by Puyi made headlines at an auction in Hong Kong. The rare Patek Philippe watch, one of only eight known Patek Philippe Reference 96 Quantieme Lune timepieces, sold for a record HK$49 million ($6.2 million), more than double the $3 million estimate. Puyi gifted it to his Russian interpreter while the Soviet Union imprisoned him. This sale marked the highest result for any wristwatch that once belonged to an emperor.

Puyi's extraordinary journey ended on October 17, 1967, in Beijing, China, at the age of 61. Despite his reign marking the end of an era, his life intersected with significant historical events, showcasing the transformation of Chinese society, from being the Last Emperor to working as a gardener at the Beijing Botanical Garden after his release by the Chinese Communist Party. His life story was made into a movie, "The Last Emperor," in 1987.

____________________

The Dark Side

By: Nathan

Going Bananas: Artwork Eaten By Museum Visitor

For years, I’ve been hearing the pros and cons of having breakfast. But this may be the first time one of the benefits of having breakfast in the morning includes that I'm less inclined to destroy an artwork at the museum I’m visiting. This is what happened to Maurizio Cattelan’s work Comedian, which has been one of the most divisive works of art in the last several years. And now it’s back in the news again because someone ate it.

For years, I’ve been hearing the pros and cons of having breakfast. But this may be the first time one of the benefits of having breakfast in the morning includes that I'm less inclined to destroy an artwork at the museum I’m visiting. This is what happened to Maurizio Cattelan’s work Comedian, which has been one of the most divisive works of art in the last several years. And now it’s back in the news again because someone ate it.

In 2019, Maurizio Cattelan gained wider recognition after he adhered a banana to a wall using duct tape at the Art Basel art fair in Miami Beach. It prompted widespread discussion on what art is and what some people are willing to spend on it. Many were insistent that Comedian was not even art at all. In that way, Comedian might even be following in the footsteps of Dada and absurdism, or possibly what Marcel Duchamp called “anti-art”.

While almost anyone can recreate Comedian if they choose, Cattelan issues certificates of authenticity for authorized versions of the work. He instructs that the banana must be affixed to the wall at a 37-degree angle 68 inches above the ground. One such version is at the Leeum Museum in Seoul, South Korea. This is where a student named Noh Huyn-soo was visiting when he started to get hungry while passing through an ongoing Maurizio Cattelan exhibition. He removed the banana from the wall and began to eat it, taking him less than a minute to do so. Everything happened so quickly that the museum staff could not react in time. While Noh explained that he was just hungry, this was likely a planned stunt since one of his friends filmed the entire incident and posted it to Instagram. This is not the first time someone has eaten a version of the work. At its original showing at Art Basel, artist David Datuna did the same thing, bypassing the velvet rope the Perrotin Gallery had put up to keep viewers at a distance. Datuna later claimed that it was not vandalism but rather a piece of performance art he later called Hungry Artist.

Art can be a lot of things, but among art’s greatest qualities is its ability to make a statement about the world and lead people toward discussion about the work itself and what it’s addressing. Comedian does just that. You can spend decades of your life learning the ins and outs of an artistic medium, applying yourself to create something beautiful, and getting the recognition of your peers and the public. Or, you can buy a banana for fifty cents at a grocery store, tape it to a gallery wall, and let the viewers do all the work for you. But probably one of the most interesting aspects of Comedian is the banana’s perishability. Think of the Ship of Theseus: a ship that becomes so old that you’ve had to replace every piece of wood, every fiber of rope, and every scrap of sail. Is it still the same ship that existed when you first built it? The same thought applies to Comedian. Bananas don’t last long on the kitchen countertop, so I don’t expect it would fare too well under gallery lights. If you have an authorized version of Comedian, I would guess you would have to replace the banana occasionally. So is it still the same artwork if you have to replace the banana? The Leeum Museum replaces the banana every two or three days. The day Noh visited, it took museum staff about half an hour to replace the banana.

When asked by the Guardian about the incident, Cattelan said, “No problem.” But I don’t think Cattelan will be overly concerned with this incident, as he’s in the middle of some legal troubles. An artist named Joe Morford is suing Cattelan for copyright infringement. Morford claims that Cattelan stole the idea for Comedian from his work Banana & Orange. Cattelan claims that he had never seen the work and had never heard of Morford before. The Leeum Museum’s Cattelan exhibition is running through July 16, 2023.

Pivar's Lastest Lawsuit

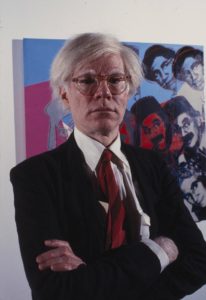

Stuart Pivar has been a fixture of the New York art market for decades. He’s been in the news for various reasons, from his behavior to his lawsuits. And now he’s hit us with another one. Pivar is now suing his lawyer for allegedly stealing a portrait of himself created by Andy Warhol in 1977.

Stuart Pivar has been a fixture of the New York art market for decades. He’s been in the news for various reasons, from his behavior to his lawsuits. And now he’s hit us with another one. Pivar is now suing his lawyer for allegedly stealing a portrait of himself created by Andy Warhol in 1977.

After founding a successful plastics company in the late 1950s, he became one of New York’s most prominent collectors. In the 1970s, he befriended Andy Warhol, who operated his workshop, The Factory, near Union Square. They walked through thrift stores and flea markets, trying to find subjects for Warhol’s works. Though his friendship with Warhol is one of the most notable parts of his biography, Pivar is mainly known as a collector of nineteenth-century realist art at a time when that market wasn’t at its strongest. In fact, he provided much of the financial backing for the New York Academy of Art when it was founded in 1980 to promote contemporary realist art.

According to court documents, Pivar sold the portrait to his attorney, Michael Cantor, for $100K. Pivar claims he was strapped for cash and agreed to sell the work to Cantor. According to Pivar, the arrangement was for Cantor to buy the painting so Pivar could buy it back for $150K within one hundred eighty days. Pivar estimates that his portrait is worth around $6M and is now seeking $10M in damages for “professional negligence and malpractice”. He claims to have arrived at that number based on Warhol’s portrait of Blondie lead singer Debbie Harry, which sold at Sotheby’s London this past March for a hammer price of £5.5M (or $6.6M).

This is not the first time Pivar has gotten into a legal spat. In 2020, he hit Sotheby’s with a $2B lawsuit after they banned him from buying, selling, or bidding through them. Similar to his ongoing suit, he sued lawyer John McFadden for allegedly tricking him into selling a Brancusi sculpture for $100K when sculptures of similar quality go for millions at auction. In 2019, he claimed to own an original painting by Vincent van Gogh. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam disputed its authenticity after viewing photos that Pivar had emailed them, leading Pivar to sue the museum for $300M. All these lawsuits were eventually dismissed. All of this is evidence in favor of Cantor, who claims Pivar is “known for making delusional claims, inventing causes of action and completely ignoring facts.” As his former lawyer, I don’t know of anyone better suited to make such an assessment.

Given Stuart Pivar’s history of filing frivolous lawsuits that are always dismissed, I don’t think it’s too difficult to draw your own conclusions about his most recent escapade.

Victory For KAWS

Over more than twenty years, the artist Brian Donnelly, professionally known as KAWS, has become one of the world’s most popular contemporary artists. He is primarily known for creating distinctive characters throughout his work, portraying them through paintings, sculptures, and merchandise. His characters are mostly humanoid figures with strange, skeletal faces that some describe as resembling Mickey Mouse. His most famous character is the figure called Companion. These characters have become incredibly lucrative because, on top of his artworks, KAWS licenses his creations to be put on clothing and made into collectible figurines. So, if you don’t have a spare $14.7 million w/p to buy the KAWS Album like one Sotheby’s Hong Kong buyer in 2019, you can get a shirt or a figurine for a couple of bucks on Amazon. But when you agree to commercialize your work, there’s always the chance that people will copy it without your permission. That’s exactly what happened to KAWS, and consequently, he’s been awarded $900K by a New York court, according to multiple news sources.

KAWS spends around $40K per year on tracking down counterfeits of his works and removing them from the market. This precaution paid off when he found several online retailers selling merchandise and art using his images. The defendant is a Singapore-based operation producing “custom hand-reworked reproductions”. These companies received a cease-and-desist letter from KAWS in 2020. When that didn’t do anything, KAWS filed a lawsuit in New York the following year, with accusations of counterfeiting and trademark infringement. According to American copyright law, a court can award up to $2 million in damages for every counterfeited marking on an item. Since these companies produced nine product categories (plush dolls, vinyl figurines, ashtrays, skateboards, canvases, posters, sculptures, rugs, and neon lights), KAWS and his legal team were asking for the maximum amount in each case. With nine types of products and two counterfeited marks per product, KAWS asked for $36 million from the court. Instead of $4 million per type of product, the court awarded KAWS $100K per type, adding up to $900K in damages. Though it may not be as much as he had hoped for, KAWS still won a significant victory allowing him and other artists to pursue legal cases against counterfeiters and forgers.

Supreme Court Rules Against Warhol Foundation

Last April, I wrote about an upcoming Supreme Court case concerning Andy Warhol’s Prince portraits. Well, the justices have reached their ruling. In a 7-2 decision, the court has decided against the Andy Warhol Foundation, finding that their licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast in 2016 does not qualify as fair use and therefore violates the copyright of Lynn Goldsmith’s original 1981 photograph upon which the Warhol is based.

Last April, I wrote about an upcoming Supreme Court case concerning Andy Warhol’s Prince portraits. Well, the justices have reached their ruling. In a 7-2 decision, the court has decided against the Andy Warhol Foundation, finding that their licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast in 2016 does not qualify as fair use and therefore violates the copyright of Lynn Goldsmith’s original 1981 photograph upon which the Warhol is based.

In 1981, music photographer Lynn Goldsmith photographed the singer Prince Rogers Nelson, who was in the middle of creating his album Controversy. In 1984, when Prince gained popularity after releasing Purple Rain, Vanity Fair ran an article about rock’s newest sensation. They asked Goldsmith if she would license her photograph as an artist reference to create an original illustration. Goldsmith agreed, and Vanity Fair paid her $400. They didn’t tell her the artist they contracted was Andy Warhol. Goldsmith insisted that this licensing would be for one use only. However, Warhol created an entire series of Prince portraits, consisting of thirteen silkscreen prints and three pencil drawings. Goldsmith was not aware of this until 2016, after Prince’s death. Condé Nast, for a special edition commemorating Prince, used Orange Prince on the front cover. The Andy Warhol Foundation had licensed the image for $10,000. After Goldsmith alleged that this licensing violated her photo’s copyright, the AWF sued her.

In this case, the central argument comes down to whether or not the AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast constitutes fair use, which has four factors. According to section 107 of the United States Code Title 17, the four fair use factors are 1) the purpose and character of the use, 2) the nature of the copyrighted work, 3) the extent to which the copyrighted work was used in the derivative work, and 4) the effect the use has on the potential market value of the original work. The first factor, regarding the purpose and character of the use, is the most important in this instance. Using a copyrighted work qualifies as fair use if the use is considered transformative. Furthermore, if the use of a copyrighted work is for commercial purposes, this often points toward the derivative work not being fair use. Fair use of copyrighted work mostly applies outside of a purely commercial setting, mainly for criticism, news reporting, education, or parody.

Originally, the District Court for the Southern District of New York granted summary judgment in favor of the AWF in 2019, but the Court of Appeals reversed that decision. The AWF relied largely on the first of the four fair use factors concerning the purpose of character of the use. According to the Foundation, taking a photograph, cropping it, and turning it orange is sufficiently transformative since it turns Prince “from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure”. The Foundation and the district court held that the other three fair use factors were unimportant.

However, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the majority, found that the Warhol print and the Goldsmith photograph both serve the same purpose: just as a portrait accompanying articles about Prince. The AWF argued that Warhol added a new expression to the photograph, which they claim made sufficient transformative use. Sotomayor dismisses this: "Orange Prince crops, flattens, traces, and colors the photo but otherwise does not alter it.” Furthermore, Sotomayor writes that the Goldsmith photograph and the Warhol print “share substantially the same commercial purpose.” So, because the print and the photo serve the same purpose, and because the print’s use by the AWF was for commercial licensing, the court decided that AWF’s actions were not fair use and therefore violated Goldsmith’s copyright.

Something important to clarify here is that Goldsmith is not alleging that all of the works in Warhol’s Prince Series are an infringement on her copyright. Only the specific use of Orange Prince on the cover of Condé Nast, as well as the fact that Goldsmith was not credited or compensated for it, is the offending incident. This might have been a different story if the print had been sufficiently transformative. You don’t need to look beyond Warhol’s oeuvre to see examples of the transformative use of copyrighted material. He frequently used copyrighted logos like Campbell’s, Coca-Cola, Brillo, and Muratti. However, the works serve not as advertisements but as commentary on contemporary consumerism.

In her dissent, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that this decision “will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge.” While protecting the arts is something that I think any thinking person would agree with, I believe Kagan, as well as Chief Justice Roberts who joined her dissent, may be overreacting. The court did not decide that the Prince Series was copyright infringement, just the one specific instance of the AWF licensing Orange Prince for use in a magazine without crediting Goldsmith. It is unknown whether Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts Inc. v. Goldsmith will set any new precedent or dramatically alter how copyright cases are handled in American courts. With relatively frequent copyright infringement accusations against some artists like Jeff Koons and Richard Prince, that may be the case. But we don’t know that right now. Now is the time to congratulate Goldsmith on gaining the recognition that she did deserve.

Artcurial Altercation

A London-based art dealer has gotten into a bit of a spat with the French auction house Artcurial. Patrick Matthiesen owns the Matthiesen Gallery, just around the block from St. James’s Square in London, specializing primarily in Old Master paintings. Recently, Matthiesen purchased the painting Narcissus, which specialists have recently reattributed to Laurent de la Hyre, a French Baroque painter and a leader of the seventeenth-century neo-classical French style now known as Atticism. Matthiesen purchased the painting through Artcurial on November 9, 2022, for €700K (or $705.6K) despite the auction house having very little provenance information on the painting. The only information about its previous owners was that it sold at Christie’s in 1929. Though he already bought the work, Matthiesen has refused to export it to Britain without first taking every precaution under anti-money laundering legislation. The gallery began independently investigating the work’s provenance because, according to Matthiesen, Artcurial refused to provide that information. “We have to know who the seller is, and, if they are an agent, to find the ultimate beneficiary. Similar rules apply in America and there is no way we could sell the painting in the US with no information on its whereabouts for almost a century.”

A London-based art dealer has gotten into a bit of a spat with the French auction house Artcurial. Patrick Matthiesen owns the Matthiesen Gallery, just around the block from St. James’s Square in London, specializing primarily in Old Master paintings. Recently, Matthiesen purchased the painting Narcissus, which specialists have recently reattributed to Laurent de la Hyre, a French Baroque painter and a leader of the seventeenth-century neo-classical French style now known as Atticism. Matthiesen purchased the painting through Artcurial on November 9, 2022, for €700K (or $705.6K) despite the auction house having very little provenance information on the painting. The only information about its previous owners was that it sold at Christie’s in 1929. Though he already bought the work, Matthiesen has refused to export it to Britain without first taking every precaution under anti-money laundering legislation. The gallery began independently investigating the work’s provenance because, according to Matthiesen, Artcurial refused to provide that information. “We have to know who the seller is, and, if they are an agent, to find the ultimate beneficiary. Similar rules apply in America and there is no way we could sell the painting in the US with no information on its whereabouts for almost a century.”

Matthiesen also claims Artcurial gave him different answers to the same question. When he asked who the painting’s most recent seller had been, auction house staff told him at one time that it came from a Belgian family and then another time that it came from a British company. He also noticed an inscription on the frame reading “scuola francesa”, or French School in Italian, indicating that the painting may have been in Italy at one point. After requesting payment twice, Artcurial canceled the sale at the seller’s request. Matthiesen has reported the incident to the relevant agencies in both France and Britain. Artcurial states that it provided as much information as possible, and it has the right to protect the anonymity of its clients. It has since described Matthiesen's claims as “erroneous, if not defamatory”. Matthiesen claims that this is not the first time that his gallery has had to perform its own research on paintings to make up for French auction houses’ lack of transparency.

____________________

The Art Market

By: Nathan & Howard

Dorotheum 19th Century Paintings

I normally don’t cover sales from continental European auction houses. However, when I saw the results from Dorotheum’s sale of nineteenth-century paintings, I knew I had to write something about it. On May 2nd, Dorotheum’s Vienna saleroom offered one hundred ninety-four lots, mainly by nineteenth-century European masters like Franz von Defregger, Marco Grubas, and Alfred Zoff. What made the sale noteworthy was not only how it did overall, but how much some of the lots exceeded their estimates by (w/p = with buyer's premium). The top lot of the sale fared exactly how the specialists predicted: Ottoman lady, preparing for an outing by Osman Hamdi Bey. The work shows an Ottoman interior scene, with a woman in a yellow robe putting on her headscarf. The painting, probably created sometime in the 1880s, is an example of Hamdi Bey’s interest in contemporary Ottoman fashion, as the details of the subject’s attire say a lot about her. The dress's color indicates she comes from a wealthy background since yellow dyes were rather expensive. The embroidered blue velvet on the sofa is in the style of Bursa artisans, while the cushions are made from silk. Paintings like this are similar to European works by Orientalist artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme and Eugène Delacroix. Though Western European painters often visited the Middle East and North Africa in their search for subjects, local customs often prohibited them from certain spaces. A woman’s living quarters were among these forbidden places, meaning that Hamdi Bey’s interior scenes, like the one sold on Tuesday at Dorotheum, fill in a lot of the gaps left by the European Orientalist painters, as well as offering far less mystical or exotic views of daily life in the Ottoman Empire. Hamdi Bey’s Ottoman Lady sold for €1M / $1.1M (or €1.275M / $1.4M w/p), meeting its assigned minimum estimate.

While Ottoman Lady fell within the specialists' estimate, the other top lots exponentially surpassed them. The works of Eugen von Blaas often show contemporary women in informal settings, their dress being significantly less ornate but at times more colorful than the ball gowns worn by the subjects of other artists. His painting The Curious shows two women taking turns scaling a ladder to peer over a tall brick wall. It is unknown what lies beyond the wall, leaving the viewer with the same curiosity that provoked the painting’s subjects in the first place. Expected to sell for no more than €160K, The Curious eventually sold for €400K / $439.9K (or €520K / $571.9K w/p), more than two-and-a-half times its high estimate. And finally, taking everyone by surprise, in third place was an unframed oil study attributed to the Polish artist Jan Matejko. The work is a study of Matejko’s colossal 13-by-26-foot historical scene Prussian Homage, which currently hangs in the Sukiennice Museum in Kraków. Like many of Matejko’s paintings, Prussian Homage shows an important event from Polish history where the Duke of Prussia swore allegiance to King Sigismund I of Poland in 1525. The study is far less populated than the final painting, but there is no doubt that they share the same subject. However, Dorotheum probably could not determine whether Matejko himself created the study or if it was a student or workshop assistant, as the auction catalogue can only “attribute” the work to the artist. Though nowhere near as massive as the final work, the study, measuring 14 by 29 inches, still captured much attention. In the end, the study for Prussian Homage sold for an incredible €230K / $252.9K (or €299K / $328.9K w/p), or over nineteen times the €12K high estimate.

The Dorotheum sale mainly stood out because of the number of lots that exponentially exceeded their estimate ranges. The Von Blaas painting and the Matejko study were certainly two of these, but there were many more. Towards the end of the auction, the landscape by the German painter Carl Millner Grazing Cows near an Alpine Lake came across the block. Millner was one of the nineteenth century's most popular German landscape painters, becoming well-known for his alpine landscapes in particular. Though estimated to sell for no more than €8K, Grazing Cows eventually sold for three times as much at €24K / $26.4K (or €33.9K / $37.3K w/p). A little earlier, On the Beach by the Czech painter Karl Spillar sold sold for €22K / $24.2K (or €28.6K / $31.4K w/p), almost four-and-a-half times its €5K high estimate. Lastly, Ilya Repin was a Russo-Ukrainian painter known for creating some of the Russian Empire’s greatest historical paintings. Repin and his works recently popped up in the news cycle when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art reclassified him as a Ukrainian artist due to the museum administration taking steps to undo Russian cultural hegemony over Slavic art. Against an estimate range of €8K to €12K, Repin’s 1888 Portrait of a Kabardian Prince sold for €65K / $71.5K (or €84.5K / $92.9K w/p), or close to five-and-a-half times the high estimate.

The Dorotheum sale mainly stood out because of the number of lots that exponentially exceeded their estimate ranges. The Von Blaas painting and the Matejko study were certainly two of these, but there were many more. Towards the end of the auction, the landscape by the German painter Carl Millner Grazing Cows near an Alpine Lake came across the block. Millner was one of the nineteenth century's most popular German landscape painters, becoming well-known for his alpine landscapes in particular. Though estimated to sell for no more than €8K, Grazing Cows eventually sold for three times as much at €24K / $26.4K (or €33.9K / $37.3K w/p). A little earlier, On the Beach by the Czech painter Karl Spillar sold sold for €22K / $24.2K (or €28.6K / $31.4K w/p), almost four-and-a-half times its €5K high estimate. Lastly, Ilya Repin was a Russo-Ukrainian painter known for creating some of the Russian Empire’s greatest historical paintings. Repin and his works recently popped up in the news cycle when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art reclassified him as a Ukrainian artist due to the museum administration taking steps to undo Russian cultural hegemony over Slavic art. Against an estimate range of €8K to €12K, Repin’s 1888 Portrait of a Kabardian Prince sold for €65K / $71.5K (or €84.5K / $92.9K w/p), or close to five-and-a-half times the high estimate.

On top of the surprises, a handful of lots had some strange estimates and hammer prices. The Dorotheum sale featured several works by artists whose work is not always the most popular, and yet the house specialists assigned outrageous estimate ranges. Even more astounding, some of these works sold far above those estimates. For example, a genre painting by Gaetano Chierici entitled Una partita a Briscola - nell’imbarazzo came across the block with a €50K to €70K estimate range. It eventually made €110K / $120.9K (or €143K / $157.3K w/p). The last time a work of his did this well was nearly four years ago at Sotheby’s London, when Surprised! sold for £212.5K w/p, and it was a much larger work - over six times the size of the painting sold at Dorotheum on Tuesday. The sale also offered a pair of works by the Italian Orientalist painter Fausto Zonaro. His portrait A Dervish sold for €62K / $68.2K (or €80.6K / $88.65K w/p), more than twice the €24K high estimate. However, what caught our attention was Sunday Promenade in Göksu, which the Dorotheum specialists estimated to sell for between €100K and €150K. Zonaro is not the most popular nineteenth-century painter in auction houses today, so specialists assigning an outstanding estimate to such a small work is beyond explanation, even if there was absolutely no dirt, craquelure, or tears in the canvas. Sunday Promenade eventually sold for €260K / $285.9K (or €338K / $371.8K w/p). Zonaro’s work has made hundreds of thousands of dollars in the past, but these were normally much larger works sold at Christie’s and Sotheby’s in the early 2010s. It makes me somewhat curious as to who is paying these astronomical prices and if something more is going on here than simply buying art.

Several highly-valued lots went unsold on Tuesday, most notably An Arab by Rudolf Ernst and Lake Wolfgangsee by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller. Despite this, the sale did very well overall. Fifty-three of the one hundred ninety-four lots sold within estimate, giving Dorotheum’s experts a 27% accuracy rate. Thirty-seven lots (19%) sold below estimate, while forty-four (23%) sold above, resulting in a 69% sell-through rate. With a total pre-sale estimate range of €3.4M and €4.7M, the sale fell nicely in the middle with a total of €4.1M / $4.48M.

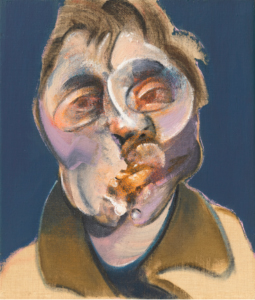

Christie’s Newhouse Collection

On Thursday, May 11th, Christie’s New York held some of the biggest sales so far this year. Before they could start their 20th Century evening sale, they first offered the works from the S.I. Newhouse collection. Samuel Irving Newhouse, Jr. was a media magnate who co-owned Advance Publications, the parent company of magazines such as Bon Appétit, GQ, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Vogue. This sale consisted of sixteen paintings by many of the great masters of the twentieth century. Though not expected to be the top lot, a self-portrait by Francis Bacon became the sale's star. Created around 1969, it’s a small work, only 14 by 12 inches, but it is incredibly striking and typical of Bacon’s beautifully grotesque style. It was previously in the collection of Bacon’s friend and dealer Valerie Beston, and it last sold at Christie’s London for a hammer of £4.6M. Bacon’s self-portrait surpassed its $28M high estimate, with the hammer coming down at $29.75M (or $34.6M w/p).

On Thursday, May 11th, Christie’s New York held some of the biggest sales so far this year. Before they could start their 20th Century evening sale, they first offered the works from the S.I. Newhouse collection. Samuel Irving Newhouse, Jr. was a media magnate who co-owned Advance Publications, the parent company of magazines such as Bon Appétit, GQ, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Vogue. This sale consisted of sixteen paintings by many of the great masters of the twentieth century. Though not expected to be the top lot, a self-portrait by Francis Bacon became the sale's star. Created around 1969, it’s a small work, only 14 by 12 inches, but it is incredibly striking and typical of Bacon’s beautifully grotesque style. It was previously in the collection of Bacon’s friend and dealer Valerie Beston, and it last sold at Christie’s London for a hammer of £4.6M. Bacon’s self-portrait surpassed its $28M high estimate, with the hammer coming down at $29.75M (or $34.6M w/p).

Behind the Bacon portrait was the sale’s final lot, Willem de Kooning’s Orestes. This is a work from early in De Kooning’s career as a purely abstract painter, experimenting with a series of black-and-white works throughout the late 1940s. It was part of De Kooning’s first-ever solo show at the Egan Gallery in New York in 1948. Orestes was last sold at auction at Sotheby’s New York in 2002 for $12M hammer, and was included in the popular 2011-12 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Sotheby’s specialists estimated it would sell in excess of $25M, and it ended up selling for $26.5M (or $30.89M w/p). Finally, Sotheby’s experts originally predicted that Picasso’s abstract portrait L’Arlésienne would be the sale’s top lot, assigning it a $20M to $30M estimate range. The subject is Lee Miller, a photojournalist who, only a few years after Picasso created this portrait, served as a Vogue correspondent in Europe for much of the Second World War. The title, referring to a woman from Arles, refers to Miller’s first encounter with Picasso, since they first met while both on vacation on the French Riviera. Picasso would create six other portraits of Miller in 1937, but the one offered at Christie’s on Thursday is one of the only ones the artist kept for himself. L’Arlésienne eventually sold for $21M (or $24.56M w/p) against an estimate range of $20M to $30M.

There are often not many surprises in a sale with so few lots, and with those lots having very high estimates. However, one work sold for exactly double its $1.5M high estimate. After Chardin by Lucian Freud was created in 1999, and serves as a sort of homage to one of Western painting’s great masters. The work is Freud’s version of The Young Schoolmistress by the eighteenth-century French still-life master Jean Siméon Chardin. This is not unusual for Freud, recreating older works while adding a few of his own personal stylistic touches. Throughout his career, Freud created his own versions of Jean-Antoine Watteau and John Constable's works. After Chardin eventually sold for $3M (or $3.8M w/p). But while I normally write about surprises in terms of pieces that sold for much higher amounts than expected, there was a surprise of the opposite kind. Roy Lichtenstein is best known for “appropriating” the works of twentieth-century comic and commercial artists. However, some of his works also reach as far back as the impressionists. I didn't think much of it when I saw Rouen Cathedral through my laptop’s screen. But it grew on me when I visited Christie’s and viewed the work in person. It’s a triptych made with oil paint and acrylic resin on canvas, each segment measuring 63 by 42 inches. The images can only be seen from a distance, with the individual dots of paint creating a clear image of the front door of Rouen Cathedral. I recognized the image almost instantly because it is based on the over thirty paintings Claude Monet created of the cathedral in 1892 and 1893. The Lichtenstein version became one of my favorite lots in the sale, but unfortunately sold far under its estimate. Christie’s specialists assigned a $18M to $22M range, but there was insufficient interest on Thursday evening. The hammer came down only at $13M (or $15.36M w/p), about 28% below what was expected.

The Newhouse Collection sale was an incredible prelude to the equally incredible 20th Century sale. Four of the sixteen lots sold within their estimates, giving Christie’s specialists a 25% accuracy rate. Another six lots (38%) sold below estimate, while six sold above. No lots went unsold. Estimated to bring in no less than $140.6M, the sixteen lots offered brought in a total of $150.4M.

Christie's 20th Century Evening Sale

Following the success of the Newhouse collection, Christie’s New York continued on Thursday evening with their 20th Century evening sale. This consisted of fifty-four lots from various collections, including that of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. Christie's sold most of the prominent works from Allen’s collection last November in the most valuable single auction in history (w/p = with buyer's premium). But while several lots came from Allen’s collection, none were among the top three. At the top was the much anticipated Les Flamants by Henri Rousseau, the great French post-Impressionist and primitivist painter. The tropical landscape has an incredible provenance, once part of the collection of Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, head of a prominent German Jewish banking family who had much of their art collection seized by the Nazis in the mid-1930s. However, this particular painting was part of the collection Paul’s widow Elsa saved when she fled to Switzerland. Knoedler & Co. bought it sometime in the 1940s before it entered the Whitney family. Joan Whitney Payson, who would later serve as president of the New York Mets in the 1960s and 1970s, purchased the work in 1949 and passed it on to her daughter Payne after her death in 1975. Being an art collector is not unusual for a member of the Whitney family. Joan’s aunt Gertrude was the founder and namesake of the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan. Everyone knew Les Flamants would set Rousseau’s new auction record even before Thursday's sale. The painting received a $20M to $30M estimate range from Christie’s specialists, plus the lot was guaranteed. Rousseau’s previous auction record had been set almost thirty years ago at Christie’s London at a 1993 Impressionist and Modern sale, where Portrait de Joseph Brummer sold for $2.97M w/p. The bidding went on for eight whole minutes before Jussi Pylkkänen brought the hammer down at $37.5M (or $43.54M w/p).

Next was Pablo Picasso’s Nature morte à la fenêtre, a 1932 still life from the collection of Jan Krugier. Krugier was a Polish-Swiss art dealer who was the first to stage an exhibition of Picasso’s works after he died in 1972. Also following his death, Picasso’s daughter Marina gave him exclusive rights as dealer of her collection of her father’s art. Nature morte à la fenêtre was created at the tail end of Picasso’s fixation on creating plaster busts of his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter. One of these is featured in the still life. After this, Picasso would go on to have a sort of annus mirabilis in 1932, according to some art historians, creating some of his most famous works, particularly his nude portraits of Walter like La Lecture, Le Repos, Jeune fille devant un miroir, and La Rêve. Having been predicted to sell for more than $40M by Christie’s specialists, the Picasso underperformed slightly, achieving a hammer price of $36M (or $41.8M w/p). And finally, something from a living artist, in third place was Ed Ruscha’s Burning Gas Station from the Alan and Dorothy Press collection. This work and five others from the same time show a Standard Oil gas station, which Ruscha would pass by during drives between his native Oklahoma and Los Angeles. Before finding its way into the Press collection, Burning Gas Station was previously owned by Larry Gagosian and the James Corcoran Gallery, from which the Presses purchased it. It eventually brought in $19M (or $22.26M w/p), just slightly below its initial $20M to $30M estimate, but nonetheless one of the sale’s top lots.

Though none of the pieces from the Paul Allen collection made it into the top three lots, all of them, regardless, did very well. There were seven paintings: three by O’Keeffe, three by Hockney, and one by Hopper. All of them sold above their estimates, with the biggest surprise being Georgia O’Keeffe’s Black Iris VI. It last sold at auction at Christie’s New York in 1998 as part of the collection of Jacob Gould Schumann III. It sold for $1M hammer back then, far below its $2M minimum estimate. Christie’s specialists this time around knew that the O’Keeffe would probably fetch a far higher price not only because of the time elapsed since the 1998 sale but because of it being from the famous Paul Allen collection. Christie’s specialists gave it an estimate range of $5M to $7M. When the time came, the O’Keeffe far surpassed expectations, achieving more than double the high estimate. Jussi Pylkkänen finally brought the hammer down at $18M (or $21.1M w/p). But the biggest surprise of the evening in general was a simple chalk and pencil drawing by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Au cirque: Éléphant en liberté shows a man in what looks like a matador’s costume forcing an elephant onto its hind legs. At the time, Toulouse-Lautrec was confined to a sanatorium outside Paris after suffering from alcohol abuse and syphilis. While there, he created about fifty drawings to prove his sanity to physicians. After his release, the artist allegedly declared, “I’ve bought my release with my drawings”. The circus scene was one of the cheaper lots available on Thursday, with an estimate range of $400K to $600K. Bid followed bid until, eventually, the hammer came down at $2.2M (or $2.7M w/p).

Overall, the sale did very well. Of the fifty-four available lots, sixteen sold within their estimates, giving Christie’s specialists a 30% accuracy rate. Ten lots (19%) sold below estimate, and eighteen lots (33%) sold above, giving the sale a sell-through rate of 81%. Expected to make at least $254.3M, Christie’s 20th Century evening sale brought in a total of $276.1M. When combined with the preceding Newhouse Collection sale, Christie’s brought in a total of $426.5M, or $506.57M w/p, in a single night.

The Mo Ostin Collection at Sotheby's New York

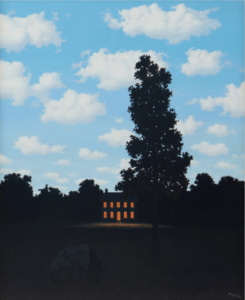

Christie’s and Sotheby’s sometimes mirror each other. That fact was more apparent during Sotheby’s sales on Tuesday, May 16, which came shortly after a pair of very successful Christie’s sales the previous Thursday. On Tuesday, Sotheby’s started with the collection of music executive Mo Ostin. Ostin spent over thirty years at Reprise Records, a subsidiary of Warner Brothers, and was responsible for signing Jimi Hendrix, the Kinks, Joni Mitchell, Prince, Neil Young, the Talking Heads, Van Halen, Madonna, and R.E.M. There were 15 lots in total, with some of the most highly anticipated being works by the Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte. Specifically, Magritte’s L’Empire des lumières was the most highly valued lot of the sale, with Sotheby’s specialists estimating it to sell for between $35M and $55M. The painting is part of a series, all showing houses shrouded in the darkness of night but with a bright blue midday sky above them. Ostin acquired the work in 1979 from fellow music executive David Geffen. The Magritte sold after nearly 10 minutes of bidding, with a hammer coming down at $36.5M (or $42.3M w/p), making it the second most valuable work by Magritte ever sold at auction. The first, interestingly enough, was another painting from the L’Empire des lumières series that sold at Sotheby’s London in March 2022 for £51.5M.

Christie’s and Sotheby’s sometimes mirror each other. That fact was more apparent during Sotheby’s sales on Tuesday, May 16, which came shortly after a pair of very successful Christie’s sales the previous Thursday. On Tuesday, Sotheby’s started with the collection of music executive Mo Ostin. Ostin spent over thirty years at Reprise Records, a subsidiary of Warner Brothers, and was responsible for signing Jimi Hendrix, the Kinks, Joni Mitchell, Prince, Neil Young, the Talking Heads, Van Halen, Madonna, and R.E.M. There were 15 lots in total, with some of the most highly anticipated being works by the Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte. Specifically, Magritte’s L’Empire des lumières was the most highly valued lot of the sale, with Sotheby’s specialists estimating it to sell for between $35M and $55M. The painting is part of a series, all showing houses shrouded in the darkness of night but with a bright blue midday sky above them. Ostin acquired the work in 1979 from fellow music executive David Geffen. The Magritte sold after nearly 10 minutes of bidding, with a hammer coming down at $36.5M (or $42.3M w/p), making it the second most valuable work by Magritte ever sold at auction. The first, interestingly enough, was another painting from the L’Empire des lumières series that sold at Sotheby’s London in March 2022 for £51.5M.

The other Magritte from the Mo Ostin collection came in second place, as the Sotheby’s house specialists expected. This one, entitled Le Domaine d’Arnheim, shows a window looking out onto snow-covered mountains. The window's glass is shattered and scattered across the windowsill and the floor. Each shard of glass is not transparent but shows an imprint of what was once behind it, almost as if someone had shattered a screen. Magritte created several works called Le Domaine d’Arnheim, all based on Edgar Allen Poe’s story “The Domain of Arnheim”, about a man who became so wealthy he took up the hobby of “landscape-gardening”, hence the mountain peak in the background sculpted into the shape of an eagle’s head. It is by far my favorite painting in the entire sale and is incredibly thought-provoking, addressing the dialogue between the man-made and the natural. This is another work Ostin bought from David Geffen in 1990. Like L’Empire des lumières, Le Domaine d’Arnheim barely squeezed by its minimum estimate, selling for $16.2M (or $18.9M w/p) against a $15M to $25M estimate range. This makes it Magritte’s fifth most valuable work sold at auction, right behind A la rencontre du plaisir, a painting that sold for $16.5M as part of an Art of the Surreal sale at Christie’s London in February 2020.

And finally, in third was a large, untitled work by the American painter Cy Twombly. The canvas, measuring about 49 ½ by 56 ¾ inches, seems almost spattered with oil paint and littered with crayon and pencil scribbles. The media are applied in a manner consistent with Twombly’s other work, nearly always straddling the line between fine art and graffiti. This untitled work has never been to auction before, having previously bounced between several private collections and galleries, including Thomas Ammann Fine Art in Zurich. After only three minutes of bidding, Oliver Barker brought the hammer down at $10M (or $11.8M w/p), falling short of the $14M low estimate assigned by the house specialists.

The sale overall did rather well. Of the fifteen lots total, five sold within their estimates, giving Sotheby’s a 33% accuracy rate. Six lots (40%) sold under, three lots (20%) sold over, and only a single lot (7%) went unsold. Since a good chunk of the sale sold for below their pre-sale estimates, the auction brought in $104.85M, only slightly above the $103.3M total minimum estimate. The fact that some lots were guaranteed, like the Mitchell, the Gorky, and one of the Picassos, likely saved the sale. Additionally, had the reserves of some lots been slightly higher, Sotheby’s may have had a small disaster on its hands.

Butkin Collection At Sotheby’s 19th-Century Sale

On May 24th, Sotheby's offered up a lower-end group of 19th-century paintings, and while it had mixed results, some of the works did rather well.

As we have seen over the past few years, the main salerooms have been trying to present important 19th-century paintings in their Old Master sales. While this is a nice idea, the problem is that they typically feature mid to lower-level examples when they create a stand-alone sale of 19th-century works. In turn, these sales perform poorly, making the market seem weak, which is not the case when it comes to quality works in good condition.

A large portion of this sale contained works from The Muriel S. and Noah L. Butkin Collection, which were being sold to benefit the Cleveland Museum of Art. Obviously, the museum decided to sell 49 works they felt did not add anything to their collection … in other words, the ‘stuff’ (though I am surprised they deaccessioned the Bargue). If you go to the museum’s website, you can see all the works they are keeping which include paintings by Tissot, Gérôme, Alma-Tadema, Bouguereau, Lhermitte, Cazin, Vibert, Bonvin, etc. Anyway, let's get on with our review.

A strong work by Charles Sprague Pearce titled The Young Shepherd came in at the top of the heap. The painting measured 42.5 x 30 inches, had been in the same family's collection for decades, and was expected to sell in the $30-50K range; it finally hammered at $130K ($165.1K w/p). Taking the number two position was a large work (59.75 x 50 inches) with some real condition issues by Johan Christian Dahl titled Waterfall in Hemsedal. While viewing the sale, we noticed that the painting had extensive pigment shrinkage, which was not disclosed in the condition report: The canvas is lined. The paint surface is stable. There are frame abrasions to the edges. There are patterns of craquelure in places. Minor scuffs and scratches in places. Inspection under UV reveals areas of retouching to aformentioned frame abrasions and craquelure, scattered areas of retouching to sky, forest and waterfall. Well, that did not seem to bother at least two bidders who took the $5-7K estimated work up to $55K ($69.9K w/p). In a close third was a small (11 x 8 inches) painting by Charles Bargue from 1878 titled The Artist and his Model. Bargue was an important French academic artist who, along with Jean-Léon Gérôme, created the Cours de dessin – an important classical drawing course. The painting was estimated to sell in the $30-50K range and hammered at $50K ($63.5K w/p).

Rounding out the top five were Václav Brožík's The Order of the Cardinal that hammered at $45K ($57.2K w/p) on a $25-25K estimate, and Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida watercolor Valenciana a la reja which made $40K ($50.8K w/p) on a $40-50K estimate.

Several works performed rather well. Rosa Bonheur's Head of an Ewe (8 x 7 inches - Butkin Collection) carried a $7-9K estimate and brought $19K ($24.1K w/p) – why? You got me! Another work described as "Italian School, 19th Century" had a $1.2-1.8K estimate and sold for $4.5K ($6.1K w/p), and Johan Frederick Eckersberg's Mountain Lake made $14K ($17.8K w/p) on a $3-5K estimate. Then they had many works that sold well below their estimate ranges; these included Jean-Léon Gérôme's Scarlet Ibis at $38K ($48.3K w/p – est. $60-80K - Butkin Collection) – I am still wondering how they came up with that estimate, Francisco Domingo Marqués's L'ancien modèle de Meissonier at $800 ($1.02K w/p – est. $4-6K), Ernest Meissonier's Portrait of Alfred Lachnitt which made $1.8K ($2.3K w/p – est. $5-7K), and François Diday's Near the Salève which carried a $3-5K estimate and sold for $1K ($1,270 w/p). And finally, there were those works that did not find a buyer; these included paintings by Goupil ($15-20K), Bonvin (est. $20-30K - Butkin Collection), Helleu ($20-30K), Vernon ($30-50K), and Pearce ($40-60K).

When the sale was over, of the 122 works originally offered, 2 were withdrawn, 86 sold, and 32 passed. The total take was $855K (1.086M w/p) on a $1.081-$1.585M presale estimate, so they needed to buyer's premium to beat the low end. Of the 86 sold lots, 50 were below, 21 within, and 15 above their estimate, giving them an accuracy rate of just 17.5%.

Sotheby's New York Master Paintings

Sometimes a single painting can make or break a sale. For example, last year’s most valuable painting sold at auction was Andy Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn, part of the Thomas & Doris Ammann collection at Christie’s New York on May 9, 2022. It sold for $170m ( or $195M w/p), constituting over 60% of the sale’s $273M total. Of course, with reserves and guarantees and all that, these lots almost always do fairly well, leading to a successful sale. But in the case of the Master Paintings sale at Sotheby’s New York on May 26th, one lot more or less carried the entire sale in a rather unexpected way. Portrait of a Poodle by Jacques Barthélémy Delamarre is a rather unimpressive painting of a small dog. The pup sits on a tabletop beside an inkwell, its fur expertly trimmed. The canvas is only 9 ⅝ by 12 ⅜ inches and was created sometime in the late eighteenth century. What drew people’s attention is that the painting’s subject is allegedly Pompon, the pet poodle of Queen Marie Antoinette. Specialists, however, are unsure of this, as Delamarre created many portraits of small dogs throughout his career. Case in point, the last time this specific portrait went to auction was at Bonhams in 1986 under the name Lowchen seated by a quill. So the royal connection might not be very strong, but that didn’t stop people from placing bids. In 1986, with Bonhams omitting the possible connection to Marie Antoinette, the painting sold for £5K (or $7.6K). Last week, Sotheby’s experts may have underestimated how much attention anything related to royalty can bring, especially famous (or infamous) royals like Queen Marie Antoinette. They only estimated the painting to sell for $5K at most. But even if you were expecting the poodle portrait to do well, you would have been incredibly surprised when the bidding continued for far longer than expected. When the $50K bid came in, I was surprised. When it reached $100K, I was astounded. And when it got its final bid of $220K (or $279.4K w/p), I was almost upset. This poodle portrait received enough attention to propel its final hammer price to forty-four times what Sotheby’s specialists had anticipated. Of course, this lot upholds my theory that paintings of dogs always do far better than expected.

The lot immediately following the poodle was the sale's second-place lot and the other big surprise of the day. Two Bathers by a Secluded Stream was commissioned around 1775 for Princess Marie Adélaïde, daughter of King Louis XV and Duchess of Louvois. It was created by the French Rococo painter Jean-Louis François Lagrenée, who had previously served as a court painter in Russia before taking on academic positions in Paris and Rome. The work is unusual because of its medium, being an oil painting on a copper plate measuring 16 ⅝ by 13 ⅜ inches. It last sold at auction at the now defunct London auction house of Peter Coxe, Burrell, and Foster, where it sold in February 1906 for £8/8 (or 8 pounds and 8 shillings in pre-decimalized British currency), or roughly the equivalent of £824 today (or $1,017). Estimated to sell for no more than $20K, the Lagrenée painting on copper sold for $150K (or $190.5K w/p), or 7.5 times the high estimate.

Third place in the sale was a tie between two Dutch paintings, one landscape, and one historical scene. The former was created by an unknown seventeenth-century artist, with the only identifying mark on the painting being a monogram containing the letters CSG. The landscape shows the city of Delft from afar, with the towers of the city's two main churches dominating the horizon. The work is more or less colorless, almost as if it’s just an etching or a charcoal drawing. However, the work is an oil painting on a panel measuring 28 by 42 ⅜ inches. The other painting, a scene from Roman history, is by Pieter Fris. Fris was better known for landscapes but chose the Death of Lucretia as his subject for this painting. According to legend, Sextus Tarquinius, son of the king of Rome, attacked and raped Lucretia, the daughter of a prominent Roman family. After telling her father and her husband, Lucretia had them swear to take vengeance, and then she committed suicide to maintain her and her family’s honor. According to the story, this set off the chain of events that led to overthrowing the Roman monarchy and the institution of the Republic. The Fris painting is clearly a product of its own time since I doubt that members of the sixth-century BCE Roman nobility would be wearing seventeenth-century European dress. Furthermore, it’s speculated that at some point in the twentieth century, the painting was touched up a bit, removing some of the blood that once covered Lucretia’s front. Some of the blood can still be seen staining Lucretia’s bodice. The retouching adds some confusion to the scene. Lucretia’s suicide was a relatively common subject for Renaissance and Baroque painters. Artists like Lucas Cranach the Elder, Rembrandt, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Sandro Botticelli have all put Lucretia’s violent end to canvas. However, most of these depictions are not overtly violent or bloody like the Fris painting seems to have previously been. Both the Delft landscape and the Death of Lucretia achieved $22K (or $27.9K w/p), the former surpassing its $9K high estimate and the latter falling nicely within the $20K to $30K estimate range.

Of the eighty-one available lots, eighteen sold within their estimates, giving Sotheby’s specialists a 22% accuracy rate. Thirty-seven lots (46%) sold below, thirteen lots (16%) sold above, and another thirteen lots (16%) went unsold. The auction made $805.2K, just shy of the $831.5K total high estimate. However, most of the sale’s apparent success can be attributed to that tiny poodle portrait, the hammer price comprising about 27% of the total. The auction would have done far worse if that royal dog had not gotten as much attention.

____________________

Deeper Thoughts

By: Nathan & Howard

But ... It Can Impact a Work's Salability

The word “but” is a conjunction that is often used to introduce a contrasting or conflicting statement. It is commonly used to indicate a shift in thought or a disagreement with a previous statement.

The word “but” is a conjunction that is often used to introduce a contrasting or conflicting statement. It is commonly used to indicate a shift in thought or a disagreement with a previous statement.

People who have worked with our gallery know that we are very particular about the art we offer for sale. Our goal is to find classic examples of the finest quality works from the artist’s best periods and in outstanding condition.

Over the years, there have been many times when clients have called us about works they saw elsewhere. More times than not, most of the pieces have issues (condition, quality, etc.), and the one thing we consistently say is that while you may like the look of the work, when it comes time to sell, the last thing you want to hear is, “Thanks for offering it to us, but…”

Are you wondering what those buts are? Well, here are a few.

But I have concerns about the work’s authenticity.

But the work has too many condition issues.

But it is not a typical work by the artist.

But it is not from the artist’s best periods.

But it is not signed.

Those sorts of buts will severely impact your ability to resell a work for a reasonable price; something we tell people to try and avoid at all costs – even if they have no intention of selling in the future. Remember, your heir may decide to sell, so why leave them with the problem.

Whether new to the art world or a seasoned collector, do your best to find works with as few buts as possible.

Mona Lisa's Bridge: A Fake Historian's Latest Claim

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa has captivated viewers for many reasons. There’s the enigmatic smile, Leonardo’s sfumato technique on full display, and the subject's mysterious identity. But few people concern themselves with the background of the work. The Mona Lisa is one of the few portraits from the Renaissance that use a completely imaginary landscape as its backdrop. So, unlike Café Terrace at Night by Van Gogh or Grant Wood’s American Gothic, you can’t go to the exact location the Mona Lisa sits in front of to recreate it for yourself. However, according to one Italian researcher, there is a part of the Mona Lisa’s background you can visit.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa has captivated viewers for many reasons. There’s the enigmatic smile, Leonardo’s sfumato technique on full display, and the subject's mysterious identity. But few people concern themselves with the background of the work. The Mona Lisa is one of the few portraits from the Renaissance that use a completely imaginary landscape as its backdrop. So, unlike Café Terrace at Night by Van Gogh or Grant Wood’s American Gothic, you can’t go to the exact location the Mona Lisa sits in front of to recreate it for yourself. However, according to one Italian researcher, there is a part of the Mona Lisa’s background you can visit.

To the right of the subject, over her shoulder, there’s a bridge. It’s one of the most discussed parts of the painting’s background since some believe that Leonardo da Vinci based the design on a real bridge in Tuscany. Many believe it is based on the Ponte Buriano, a bridge that spans the River Arno about five miles outside Arezzo. At least, the surrounding town would like you to think so. The local government has asserted this in trying to promote tourism. But now, Silvano Vinceti is putting forth another candidate. He claims that the Ponte Romito, a now-ruined bridge on the Arno seven miles west of the Ponte Buriano, is the structure depicted in the background of the Mona Lisa.

Vinceti claims that the bridge in the painting has four arches and, therefore, could not be the six-arched Buriano bridge. Though only a small part of the Ponte Romito remains, the bridge had four arches when it was in use. Vinceti claims that Leonardo must have used the structure as a model while staying in the nearby town of Laterina. But of course, identifying the background bridge is difficult since any bridge in Tuscany with four arches could have inspired Leonardo. But beneath the marvel of this development, something is unsettling about this whole story. Many focus on the story, but they should instead focus on the one who’s telling it.

Silvano Vinceti is a researcher that has spent an incredible amount of time studying the Mona Lisa. But calling him a “researcher” may be giving him a little too much credit. He’s the kind of scholar one would never see in a library or a university classroom. Instead, he seems like a character from a Dan Brown novel. Some may remember Vinceti as the researcher who exhumed the body of Lisa del Giocondo, who many agree was the Mona Lisa’s subject. He wanted to perform tests on the corpse, including facial reconstruction, to not only see if she was the Mona Lisa’s subject but to hopefully dispel any rumors that the Mona Lisa was a feminized self-portrait. Vinceti has done this before with other Italian figures, including Petrarch and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, opening up their tombs to perform forensic tests. His fixation on the Mona Lisa has lasted several years, with his theories remaining unsupported by art historians and technicians. For example, he once claimed he found someone's initials painted into the Mona Lisa’s eyes. He also proposed that the Mona Lisa is a composite portrait, combining Lisa del Giocondo's facial features with those of Leonardo's student and possible lover Gian Giacomo Caparotti, who became known as an artist under the name Salaì.

I first became suspicious of Vinceti when he told CNN that his interest in Da Vinci is very personal because they share many attributes. One of them he mentioned that surprised me was that Leonardo “never went to university, didn’t learn Greek or Latin, and was not considered learned.” That’s always reassuring to hear from someone claiming to be an authority on Italian Renaissance figures. I dug a little deeper, and I found that Vinceti has no real training or experience as a historian, art restorer, art conservator, or forensic scientist. He has never taught in a classroom, and he has never had any research published in any credible academic journals. Before he started digging up bodies, he was a television presenter. He presented documentaries, some of them on Italian history. Some may argue that this is not equivalent to earning an advanced degree and learning how to perform historical research. Sitting around in the archives poring over manuscripts must not have been sexy enough, so Vinceti decided to make it sexy by pitching himself as a real-life Indiana Jones of some kind.

Vinceti’s escapades have produced occasional results, though. When he exhumed the body of Pico della Mirandola, forensic analysis indicated that he had died from arsenic poisoning. When he opened Petrarch’s tomb in Arquà, he found someone had replaced his skull with a young girl's. While some of these were interesting discoveries, they were not the breakthroughs that some heralded them as. That someone stole Petrarch’s skull in the six-hundred-fifty years following his death does not change how readers interpret his poetry. Tracking down the remains of the Baroque painter Caravaggio did nothing to revolutionize the way we view his shadowy canvases. And claiming that one bridge or another is the one in the Mona Lisa's background will do very little to advance scholarship about Da Vinci, his works, or the wider Italian Renaissance period. Vinceti's work not only does it do nothing to further academic debate, but it distracts people from the real conversations that experts in the field are having about these subjects. So I'd take everything he says with a grain of salt.

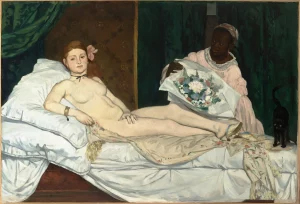

Olympia's New York Debut

Édouard Manet made a name for himself in the 1860s by becoming one of the biggest names in the burgeoning modernist movement. His works shocked audiences for several reasons, one of which was nudity. Nude figures were nothing new to the arts in nineteenth-century France, but Manet did something very different. This is best seen in some of his major paintings, one of which is finally leaving France and making its American debut at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Édouard Manet made a name for himself in the 1860s by becoming one of the biggest names in the burgeoning modernist movement. His works shocked audiences for several reasons, one of which was nudity. Nude figures were nothing new to the arts in nineteenth-century France, but Manet did something very different. This is best seen in some of his major paintings, one of which is finally leaving France and making its American debut at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Olympia is a painting of a nude woman reclining on the bed. Manet first exhibited Olympia at the Paris Salon in 1865, where it was absolutely scandalous. Manet had modeled the work on Titian’s Venus of Urbino but made several major alterations. Whereas painters before used nude figures only in biblical or mythological scenes, Manet showed a sort of everyday nudity. His nude figures were not goddesses or heroines of ancient myths, but people the likes of which you could run into on the street. The public first saw this in his 1863 painting Déjeuner sur l’herbe, or Luncheon on the Grass, showing a pair of young Parisian gentlemen having a picnic in the Bois de Boulogne park with a couple of prostitutes, one bathing in the stream and the other completely nude sitting next to the fully clothed men. Salon audiences knew that these women were probably prostitutes since it was a sort of open secret that the Bois de Boulogne was where young men procured such women at the time. Olympia was another one of these paintings.

While the Venus of Urbino shows a reclining nude woman, the subject seems completely unconcerned about her nakedness. In the background, a pair of servants rummage through a chest to give her something to wear. She holds a bouquet, perhaps gifted to her by the viewer, while at her feet, there’s a small dog, a traditional symbol of fidelity. In Manet’s Olympia, the subject does not appear unconcerned; rather, many have described her expression as confrontational. She ignores the flowers her servant is giving her, while a standing black cat, a symbol of promiscuity, has replaced the resting dog. Olympia is also a large canvas for such a subject, measuring over four feet by six feet. Canvases of this size were often reserved for academic historical paintings and other more acceptable genres. Finally, there was the name. Nineteenth-century audiences may have associated the name Olympia with prostitutes. Europeans likely made this connection because of Olimpia Maidalchini, sister-in-law of Pope Innocent X, described by Théophile Gautier as “that great Roman courtesan on whom the Renaissance doted”.

In 1890, Claude Monet spearheaded an effort to buy Olympia from Manet’s widow Suzanne and then donate it to the French government. In 1907, the state finally hung the painting in the Louvre; it was moved to the Musée d’Orsay when it opened in 1986. But now, starting on September 24th, Olympia can be seen by New York audiences as part of an upcoming Met exhibition on both Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas. The Met has also managed to secure Degas’s The Bellelli Family. The exhibition, which runs from September 24, 2023, to January 7, 2024, will examine the two artists’ relationship and how it sometimes deteriorated.

Rejects: The Salon That Changed the Art World

For nearly a century and a half, the Paris Salon stood as the most esteemed art exhibition in the world. Though it was originally established as a show for the recent graduates of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, over time, it became a space where artists from across Europe and North America would compete to not only have their works chosen for exhibition but to have their works judged by a jury of Academy faculty. The Salon and those who ran it became the arbiters of artistic taste. Renoir once wrote, “In Paris there are scarcely fifteen art-lovers able to appreciate a painter outside the Salon. And there are 80,000 who wouldn’t buy a picture of the nose on their face if it wasn’t painted by a Salon artist.” In other words, why do you need a good eye for art when the Academy jury makes all the decisions for you?

The Salon became such an authority in the arts that it became nearly impossible to make a living as an artist in Europe, and France particularly, without being chosen for exhibition. Of course, this caused a bit of discontent among artists, especially those who were not working within more established genres, which were mainly realist, academic styles like historical scenes, landscapes, portraiture, and still lifes. Of course, this was a perfectly suitable arrangement for artists who did work within those genres, like Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and Jean Léon Gérôme. However, the Académie des Beaux-Art often excluded many painters seeking to experiment with different subjects and new techniques. But 1863 became a pivotal year for these artists.

That year, the Academy made their choices, selecting several thousand works including some by Corot and Gérôme, as well as Jean-François Millet and Charles Daubigny. However, when the Academy released its selections, many realized they had rejected nearly two-thirds of all submitted works. While the complaints and protests of rejected artists normally fell on deaf ears, they did manage to make their way to one of the people who had the authority to do something about it. Emperor Napoleon III was known for being incredibly sensitive to public opinion and often felt the need to please absolutely everyone. So, in response, he decreed that a separate salon be curated for all those rejected by the Academy jury. And it certainly is fortunate that the emperor took action because then Paris would have been deprived of some of the earliest modernist masterworks. The two paintings most often considered the exhibition’s best were listed in the catalogue as Le bain and Dame blanche. These two works would be popularly known as Édouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass and James McNeill Whistler’s Symphony in White No. 1.

One hundred sixty years ago, on May 15, 1863, the Salon des Refusés, or the Salon of the Rejected as it came to be known, opened to the public, attracting around a thousand visitors each day it was open. The salon included a mixed bag of artworks. Still, one of the most represented groups was the early modernists, including Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Johan Jongkind, Henri Rousseau, and James McNeill Whistler. Exhibitions of rejected Salon entries had been held before, but they were always privately staged by artists themselves, most notably Gustave Courbet when the jury rejected many of his works. Furthermore, these private salons were never held on the scale of the Salon des Refusés.

The Salon des Refusés was held only twice more, in 1864 and 1873. Even though the Salon des Refusés was a compromise to appease protesting artists, it ended up being the beginning of the end for the Salon. The rejected works being exhibited formed the cracks in the ultimate authority of the Académie des Beaux-Arts as the final judges of artistic quality. French society could now view the paintings and sculptures considered subpar or even distasteful by the jury, leading many to decide for themselves whether the jury’s final selection had any merit. Furthermore, the Salon des Refusés showed that it was possible to exhibit works outside the Salon successfully.

The Salon des Refusés was held only twice more, in 1864 and 1873. Even though the Salon des Refusés was a compromise to appease protesting artists, it ended up being the beginning of the end for the Salon. The rejected works being exhibited formed the cracks in the ultimate authority of the Académie des Beaux-Arts as the final judges of artistic quality. French society could now view the paintings and sculptures considered subpar or even distasteful by the jury, leading many to decide for themselves whether the jury’s final selection had any merit. Furthermore, the Salon des Refusés showed that it was possible to exhibit works outside the Salon successfully.

After the initial Salon des Refusés, the Academy juries became less and less strict, but that was not enough for many artists. The Salon des Refusés became a sort of rallying cry for artists whose works were continually rejected by the Academy juries, though their pleas were often ignored or rejected. This was especially true for the members of the nascent Impressionist movement, leading these artists to band together to form the Anonymous Cooperative Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers. This group eventually organized the first independent Impressionist exhibition in 1874. By 1881, the Salon was no longer a state-backed event, instead being placed in the care of a private organization, the Société des Artistes Français. And finally, by 1890, the Société des Artistes Français had fractured into several rival organizations, and the single, unified Salon was no more. Exhibitions were still commonplace across Paris, instead being put on by a number of different artists’ organizations like the Société des Artistes Indépendants, the Salon d’Automne, and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.