|

Reflecting the Real

Click on a painting below to start the exhibition

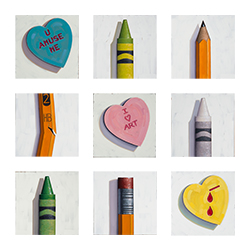

Anthony MastromatteoWhere Art Often Starts Anthony MastromatteoWhere Art Often Starts |

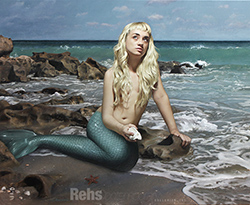

Todd M. CaseyThe Great Escape Todd M. CaseyThe Great Escape |

Kevin M. WuesteThe Dutch Boy Kevin M. WuesteThe Dutch Boy |

Lauren SansaricqWinter Sunset Lauren SansaricqWinter Sunset |

Angela CunninghamDried Roses Angela CunninghamDried Roses |

Nancy FletcherSelf Portrait with Butterflies Nancy FletcherSelf Portrait with Butterflies |

Sarah LambCamellias Sarah LambCamellias |

Carol BromanAbeyance Carol BromanAbeyance |

Irvin RodriguezLioness Irvin RodriguezLioness |

Lauren SansaricqEarly Autumn on Long Island Lauren SansaricqEarly Autumn on Long Island |

Devin Cecil-WishingBeginnings and Ends Devin Cecil-WishingBeginnings and Ends |

Camie SalazThe Rhodora Camie SalazThe Rhodora |

Edward MinoffLost Horizons No.2 Edward MinoffLost Horizons No.2 |

Anthony MastromatteoWhere Art Often Starts Deluxe - Set of 9 Anthony MastromatteoWhere Art Often Starts Deluxe - Set of 9 |

Justin WoodStill Life with Cantaloupe and Prosciutto Justin WoodStill Life with Cantaloupe and Prosciutto |

Tony CuranajOpposed - Red Peppers and Green Tomatoes Tony CuranajOpposed - Red Peppers and Green Tomatoes |

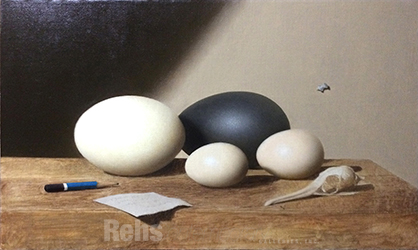

Devin Cecil-WishingVanitas Devin Cecil-WishingVanitas |

Daniel GrantLife & Death Daniel GrantLife & Death |

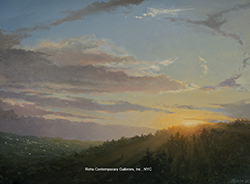

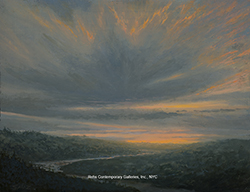

Ken SalazSunset Over Catskills - Hawks Nest 1 Ken SalazSunset Over Catskills - Hawks Nest 1 |

Travis SeymourStill Life with Water Jug Travis SeymourStill Life with Water Jug |

Ken SalazCatskill Sunset 1 Ken SalazCatskill Sunset 1 |

Erik KoeppelFlorida Sunset Erik KoeppelFlorida Sunset |

Tony CuranajBee Tony CuranajBee |

Ken SalazSunset Over Catskills, Hawk's Nest, New York Ken SalazSunset Over Catskills, Hawk's Nest, New York |

Todd M. CaseyThe Shamrock II, Study Todd M. CaseyThe Shamrock II, Study |

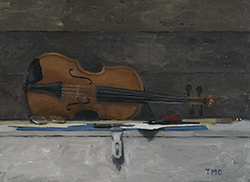

Todd M. CaseyViolin (Study) Todd M. CaseyViolin (Study) |

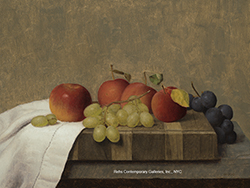

Justin WoodCrabapples and Grapes Justin WoodCrabapples and Grapes |

|

By Gabriel P. Weisberg

Professor of Art History

University of Minnesota

When Alfred Barr, the first Director at the Museum of Modern Art in the 1930s, discussed Surrealist paintings as representing “magic realism” he might have had other issues in mind. Realism in the United States was then a rampant movement, one that found many adherents such as Raphael and Moses Soyer, among others; it was also a tendency toward painting things seen and observed that many artists practiced, especially those trained in traditional approaches, such as espoused by the Art Students League in New York City. Significantly, Realism continued as a way of creating art through the heyday of the Abstract Expressionists, through to the New Realism of many artists working in a manner similar to, although not imitative of, Chuck Close. Pure realists, those who understood the way the academy had trained painters in the nineteenth century, were also active. They went underground during the latter part of the twentieth century as realism was seen as passé, out of date with the times. But, curiously, realism was maintained by many artists in the twenty-first century who practiced a method of creating that was in revolt against abstraction, surrealism, or experiments in performance art. The artists associated with the Grand Central Atelier or the Water Street Atelier in New York, as well as artists trained in other academies in the United States and Europe, have maintained their traditional roots. Their educational methods need to be studied anew for the ways in which these artists have been mentored regardless of where they might be located. The ways in which they have been nurtured has also led them to value certain types of themes in their paintings, subjects that are referenced in this current exhibition at the REHS gallery in New York City.

TRAINING

Understanding that traditional artists have been trained in certain ways underscores how artists at Grand Central Atelier have been mentored. Working from plaster casts, from life models, and from arrangements of still life examples is at the core of their education. In this way, and through careful discussion with their teachers, the time-tested approach to creativity has been inculcated. By beginning their studies with drawing, artists have been able to absorb the process of careful looking so that they can understand the objects or person in front of them. Having periodic exhibitions of their work produced in the studio, with prizes for the best examples from a given class effort, links these approaches with the Parisian pedagogical approach of the prestigious École des Beaux Arts or the independent atelier of Rodolphe Julian, where there was a less competitive approach. The training that artists received at these schools facilitated successful independent careers where their works were sought after, secured for public and private collections, and where official portraits were often commissioned from the artists themselves. Training counted. It is the same today with the artists in this current exhibition.

THEMES OF CREATIVITY

Artists typically organized their works around well-established thematic categories: portraits, still lifes, landscapes or fantasy compositions. This process provided examples from the past that contemporary realists could study and appreciate. They also were able to group their compositions within recognizable patterns that made it easier for collectors to understand what they were trying to accomplish.

The interest in producing portraits became a dominant direction. The more an artist could convey the likeness of a sitter; the better would be the reception of the piece when completed. In one work, a self-portrait, the sitter reveals a thoughtful presence which is accentuated by the way in which she has been placed in front of a decorative background filled with floating butterflies. Whether this background provides a type of hidden symbolism as a key to the model’s personality or character remains unknown. The effect, however, is to force someone to look more closely at the work itself so that the person depicted can be studied. The chance of creating numerous portraits fulfills one of the basic tenets of the academic education while also providing those who work in this vein with a lucrative means of survival through commissions.

Although critics often derided still-life painting in the nineteenth century as an art of mindless copying, still-life persevered, being practiced by some of the leading avant-garde painters of the era from Édouard Manet to Paul Cézanne. The modesty of the approach toward still-life painting forced artists to be observant of the objects they selected for their compositions. The same attitude infuses the ways in which still-life painters work today. The effectiveness of their simple, honest compositions which use a very few objects observed patiently recalls the ways in which Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin worked in the eighteenth century. There are many mentors to look at, although the still-life paintings in this current exhibition belie a directness that, while seemingly photographic, reinforces the notion of magic realism commented on by Alfred Barr.

In one example, the artist has placed his forms on a simple wooden table top, where the grain of the wooden planks have been meticulously conveyed. By positioning the forms close to a viewer, the artist forces an observer to notice the nuances of light that strike the forms; similarly, the texture of some objects reinforces the way in which the painter has recorded the sails of a ship model bathed with light. There is no way in which one can move away from the objects themselves as the background plane is dark; nothing intrudes on the way in which the objects have been arranged. The silence of this type of composition pervades everything, making the composition even more compelling to contemplate. Other still-lifes, developed from a set-up in the studio, create the same reactions. The simplicity of the object selection enhances the directness of vision that the painter wants to convey either by painting a ceramic container with flowers or from a grouping of eggs on a spare, wooden tabletop.

A number of artists also found the completion of landscape paintings significant. Developed from studies made on the spot or reframed by painting the scene from memory in the studio, artists completed sweeping vistas of locations that they knew well. Whether they selected a View from Fort Ticonderoga in New York State or simply recorded the ways in which waves and surf came ashore, the painters completed images that were reminiscent of earlier models such as those found within the tradition of the Hudson River School. Similarly, a work such as Early Autumn, Long Island suggested ways in which the Barbizon landscape tradition in France was being reexamined by artists eager to reflect on the many moods and the changing light effects of nature. Working in this way allowed the painters to reactivate a category of creativity that was well established while providing artists with an opportunity to reflect on views of the real world.

When developing a fourth category, “fantasy paintings” peopled with mermaids or hybrid forms, the artists often used their imaginations to create experimental compositions that stressed unusual evocations. Painted with a meticulous attention to detail, these shapes were both anti-modern and real. These canvases are being added to the pantheon of what was acceptable as a realist approach.

Trained to paint what was visible, avid students of painters from the past who worked in this way, have made the contemporary realists a powerful force. Finding many ways to paint reality has given these artists an opportunity to reactivate tradition with new life, thereby making their numerous works fervent examples of the ways in which the past can be reflexive and motivating for a new era.

________________________________

For further discussion see Gabriel P. Weisberg, et al., On the Training of Painters: The Atelier’s Past and Present, Minneapolis, 2011. |