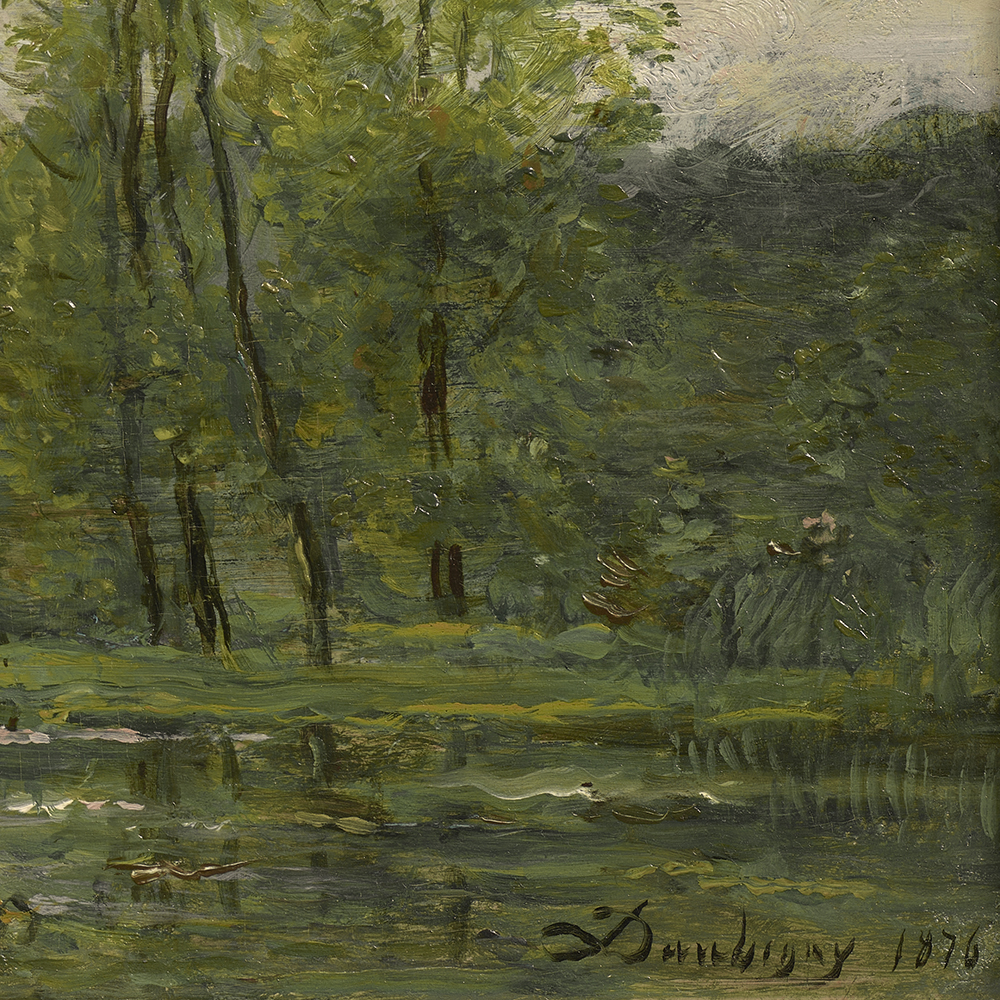

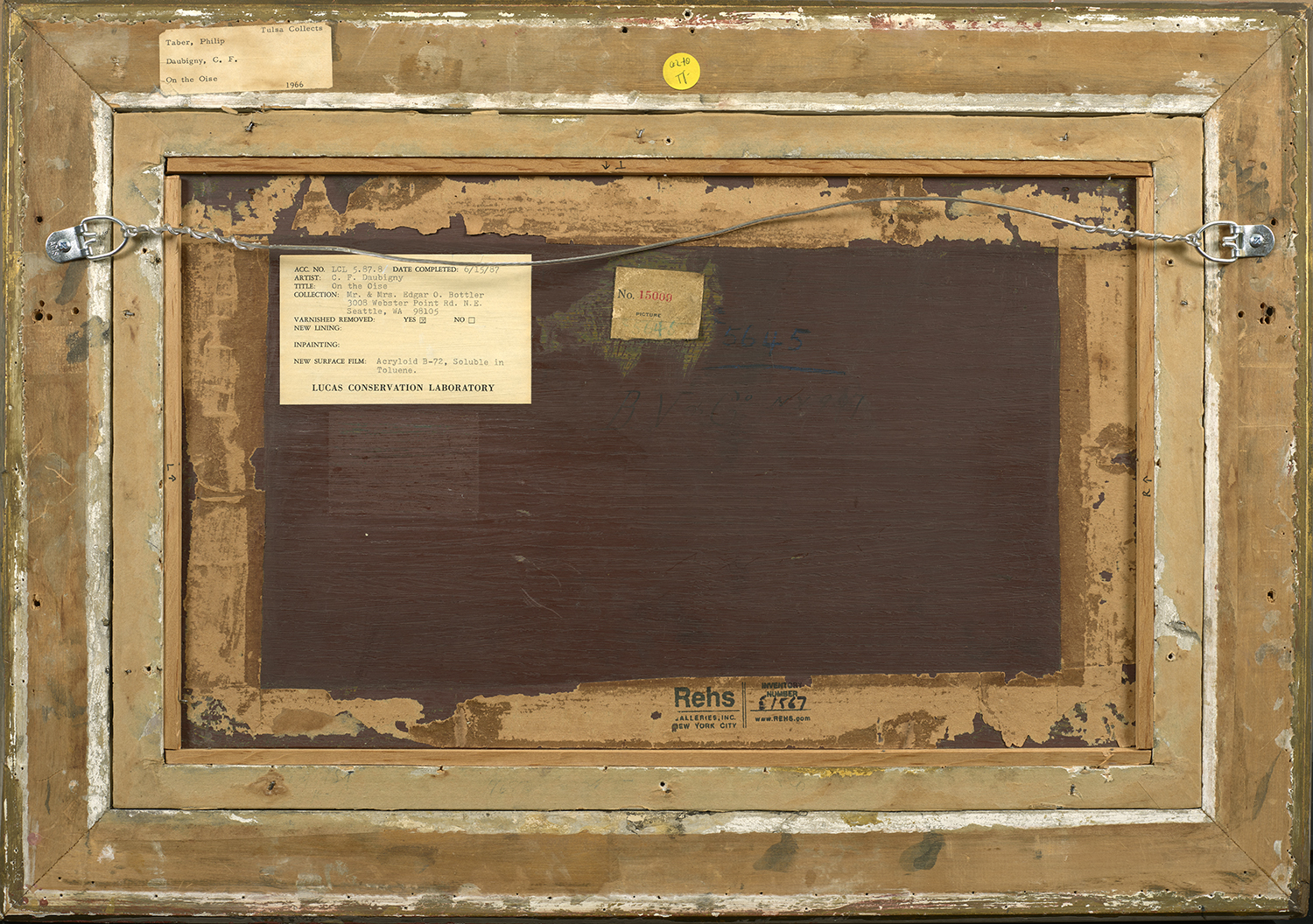

Charles Francois Daubigny

(1817 - 1878)

Sur l'Oise

Oil on panel

12 x 19.5 inches

Framed dimensions:

18.75 x 26.5 inches

Signed and dated 1876

BIOGRAPHY - Charles Francois Daubigny (1817 - 1878)

During the nineteenth century, several progressive artists emerged who impacted the future direction of art and its public acceptance; Charles-François Daubigny was one of these artists, influential through his work, and also as a fervent supporter of the emerging Impressionist group. Even though he became a well-established landscape painter, his work often solicited mixed responses from critics that lasted throughout his public artistic career. As he matured in his career and his work, so did his style, and although he attained success, those pictures most appreciated by the public were those least appreciated by Daubigny himself, attesting to his work’s dual nature of salability and progressiveness. Like many other artists, his style opened the doors for the younger generation, but Daubigny combined his talent for painting and printmaking with a will to uphold the ideals of his artistic taste by taking decisive action that often showed his support for newer tendencies.

Charles-François Daubigny was born on February 15, 1817 in Paris. He wrote that he knew how to paint before he knew how to read; drawing came naturally to him, an unsurprising fact considering that his father, Edme Daubigny, a student of Jean-Victor Bertin, was also an artist who exhibited landscape paintings at several Salons. When he was nine, his mother sent him to live with a caretaker in Valmondois in the Val d’Oise region, a woman whom he would affectionately refer to as Mère Bazot. He left Valmondois in 1826 but remained attached to this village and to Mère Bazot. The location often figured as a key component for inspiration for his later works. After returning to Paris at fifteen, Daubigny began decorating clock faces, jewelry boxes, and fan bases to assist the family income. To further continue his artistic inclinations, he began working at the Louvre in 1834 restoring old paintings, for which he received five francs apiece, and later painted decorative panels at the Château of Versailles. This work was undertaken mainly to provide Daubigny sufficient funds to undertake proper artistic training, and in 1835 he entered the atelier of Pierre-Asthasie-Theodore Sentiès, an academic painter. While Daubigny showed works far from an academic style of painting, Sentiès was a suitable teacher for him at the point in his life since he was seeking acceptance from the Salon and the art world of Paris, with his loftiest goal being to obtain the Prix de Rome of 1837.

The Prix de Rome was given every four years to a talented young art student who then would be able to study in Italy at the Villa Medici for a period of four years; the award also ensured the winner with a guarantee of success upon his return to France. But Daubigny and a fellow painter, Henri Mignan, took matters into their own hands and used extra money they had earned from their small jobs, pooled it together, and by February of 1836 the two aspiring artists had saved enough to depart on their own journey through Italy. They reached Rome in April 1836; where they discovered landscapes very different from what they had seen before. Rather than spending their time admiring works in Italian museums, as most other artists did, they spent the majority of their time outdoors, experiencing nature in a setting that was unique and inspirational. The two men spent almost two months traveling throughout Italy and returned to Paris in November, 1836. Daubigny immediately re-entered Sentiès atelier and continued his work towards the Prix de Rome, deciding, after his travels through Italy, to concentrate on historical landscape for the contest. He passed the initial exam but did not make it through the second level. Still, he was determined to continue and decided to wait the four years to try again. He was accepted for the first time into the 1838 Salon, exhibiting Vue de Notre Dame de Paris et de l’Île Saint Louis (View of Notre Dame of Paris and the Île Saint-Louis) alongside his father, a fact that mitigated his disappointment over the rejection at the 1837 Prix de Rome competition.

His first success at the Salon prompted him and his colleagues to band together to form a sort of artistic association. Early in his artistic career, Daubigny had established a group of friends while living 54 rue Vieille du Temple, including Victor Geoffroy-Dechaume, Louis Trimolet, and Louis Steinheil. In an attempt to capitalize on each of their mild successes, they took the unusual step of coming together as a small association, in a show of seemingly selfless camaraderie and economic initiative. The arrangement is described in the most recent and definitive work written on Daubigny, in which Madeleine Fidell-Beaufort and Janine Bailly-Herzberg note that “as a group they were imbued with the doctrine of Fourier and the image of an ‘artistic phalanstery’ dominated their thoughts. Daubigny, Geoffroy-Dechaume, Trimolet and Steinheil decided to pool their resources and to each year designate one, among them, to be a candidate at the Salon. During the time necessary for the preparation, the elected one and his family would be financed by the three others.” (Daubigny, Fidell-Beaufort, Madeleine and Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Paris: Editions Geoffroy-Dechaume, 1975, pg. 36) As a part of this group Daubigny completed his first wood engravings and etchings and also was commissioned to illustrate a guide to the Château of Versailles. At busy times, commissions were handed from one artist to the other which would guarantee that each artist had sufficient work. The group did not last long but did give Daubigny valuable experience in printmaking and landscape drawing, in both of which he would later become prolific.

During the four-year hiatus between the 1837 and 1841 Prix de Rome competition, Daubigny still focused on preparing himself. He had traveled to Rome and worked on new landscapes, gaining more experience with his commissions that had come through the association formed with his colleagues. Though this training proved extremely valuable, he also realized that since he was entering in the category of historical landscape painting, he would need to be accepted into another Salon before he could have any chance to win the competition. To this end, he enrolled in the atelier of Paul Delaroche, a popular academic artist, and was accepted to both the 1840 and 1841 Salons, with Saint Jérome dans le Désert (Saint Jerome in the Desert) and Vue Prise dans la Vallée de l’Oisans (View from the Valley of Oisans) in 1840 and Vue sur les Bords du Furon près de Sassenage dans l’Isère (View from the Banks of the Furon near Sassenage in Isère). Each success further encouraged his entry into the Prix de Rome. Daubigny specifically used a more historically and thus academically oriented work – Saint Jerome – which appealed to the critics and Salon jury, an act that shows his youth and his dependence on the academic system of the period.

The Prix de Rome competition began shortly after the Salon opening of 1841. He submitted a sketch of a historical landscape and “a tree standing out against the sky” (Fidell-Beaufort, Bailly-Herzberg, pg. 39); he passed the first two exams but did not realize that he was supposed to be present at the school the day prior to the third and final examination, lunching instead with a friend at Vincennes. Because of this oversight, Daubigny lost his chance to be considered for the Prix de Rome of 1841, but which, in the end, may have allowed him to explore other avenues that would eventually take his art to a level of independence from established traditions that might not have otherwise developed had he been successful in the academic competition.

This was Daubigny’s last attempt at the Prix de Rome and he began producing more illustrations for texts to earn his living, including La Pléiade and Le Jardin des Plantes. He also gained commissions under H. Delloye such as Chants et Chansons Populaires de France, to which Trimolet and Steinheil also contributed. Despite his commitments to illustrations, he submitted regularly to the Salon during this period, taking occasional trips back to his childhood village of Valmondois and other travels where he would look for inspiration for his new prints and paintings. He received his first medal—a second-class medal— at the 1848 Salon; this award also brought him a state commission for an etching of Claude Lorrain’s Abreuvoir (Watering Hole). A state commissioned etching was a clear indication that Daubigny, not only a painter, but also as an etcher, had arrived at a point of acceptance in the art world. This was also during a period in which etching was receiving more acceptance as an artistic medium, spearheaded in 1862 by Alfred Cadart who began the Société des Aquafortistes, of which Daubigny was one of the strongest supporters. Both media were important in Daubigny’s oeuvre throughout his career.

Yet, this increase in his popularity also incited criticism. From his earliest times, though increasingly so as his work began to progress, Daubigny showed an affinity with nature, which he used with his personal style and execution to create an individual body of work. Many critics of the period began to attack his work, often beginning with a praiseworthy account of his recent submission to the Salon, but ending with a charge against his poor execution. One account given after the Salon of 1852 typifies this misunderstanding of Daubigny’s work (Fidell-Beaufort, Bailly-Herzberg, pg. 45):

Mr. Daubigny is again to be found among the new landscapist group. I do not know anyone who was a more intimate feeling for nature, and who can better make it felt. But why does he only produce rough sketches like La Moisson and the Vue Prise sur les Bords de la Seine. This latter is particularly beautiful. Is Mr. Daubigny afraid of ruining his work by finishing it? But that would be an avowal of weakness. I have a better opinion of his talent and I am convinced that a man who has begun so well could not finish badly.

Daubigny had begun his career as a young art student like many others, seeking acceptance from the Salon, training in a historical landscape style, and attempting to win the Prix de Rome contest. Yet his interest in landscape painting began extending beyond that which he had been taught. Fidell-Beaufort and Bailly-Herzberg note that these remarks “…clearly demonstrate the twofold aspect of his art; first, the traditional, as a result of his academic training, the other, more revolutionary aspect, derived form his direct contact with nature.” (Fidell-Beaufort, Bailly-Herzberg, pg. 45) This newer style, which incited so much controversy, was exactly that which would become an inspirational force for the younger generation of artists. Daubigny stressed independence form rules combined with his determination to leave his finished painting in the state of the sketch.

Daubigny’s appreciation of nature was nurtured through several trips he took in 1857. Besides travels to Italy, the Burgundy region, Cremieu, Valmondois, Lyon, he also traveled to Switzerland with his friend Camille Corot, a fellow landscape painter who is associated with the Barbizon school of painting. Daubigny is also linked with this region and the artists who painted there, despite his never having lived in Barbizon. In 1857 he bought a small boat christened “the botin” which included a covered room which he turned into a small studio. The honorary captain was his friend Corot, and his son was the cabin boy. He used this boat every summer for several years, floating along the Seine, capturing fragmentary moments of the light and landscape that he viewed along the river. These boating escapades also provided ample subject matter for his “Botin” that Daubigny began integrating water into his landscape paintings, just as the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet, would later use water in many of their paintings.

Daubigny would remain an ardent supporter of these emerging artists, including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, among others, and he would, as a Salon juror, exercise his right of opinion. He was first elected to the Salon jury in 1865, but resigned when Pissarro and Cézanne’s works were rejected. Of his choice Daubigny said that he “preferred paintings full of daring to the nonentities welcomed into each Salon.” (Fidell-Beaufort, Bailly-Herzberg, pg. 57) As a pacifist, resignation was Daubigny’s strongest form of protest, but he also suggested to those rejected that they continually form a Salon des Refusés, a Salon for all of the refused artists as a protest against the Salon itself, as had happened in 1863. These were strong instigations from an artist who, in his early career, had worked so hard to be accepted at the Salon. He was also elected to the 1868 and 1870 Salon juries and further tried to use his position to support the younger creative artists. Once again, in 1870, however, he resigned his position after one of Monet’s submissions was rejected by the Salon jury.

This same year, the Franco-Prussian war broke out and Daubigny moved his family to London where many artists were seeking refuge. He was commissioned by the art dealer Durand-Ruel to complete three paintings which were based on sketches of Villerville, one of the many towns that Daubigny frequented. In yet another show of support for the younger artists, he tried to persuade Durand-Ruel to purchases pictures by Pissarro, Monet, and Francois Bonvin. He and his family returned to Paris after calm returned in the city. He returned not only to Paris but also to his “Botin”, beginning again his summers along the Seine. He also set out on a journey to Holland with his son Karl, where they spent a short time sketching windmills while traveling along the river, inspiring a work that was exhibited at the 1872 Salon: Les Moulins de Dordrecht (The Windmills of Dordrecht).

At the Salon of 1873 it became clear that Daubigny’s work had become more “impressionistic”, though it was a year before the term was even established. His painting, L’Effet de Neige (Effect of Snow) ca used a flurry of criticism for its unfinished nature. These were exactly the complaints that would be held against the Impressionist group just a few years later.

He continued exhibiting at the Salon and served on the Salon jury of 1875, before resigning yet again because of the rigid standards to which the jury members held for the submissions. In 1876 he and his wife Sophie began traveling again, going through the valley of the Arques and then through Normandy. His previous afflictions with gout, bronchitis, and asthma were getting much worse as time passed. Work was increasingly difficult; he exhibited the last time at the Salon of 1877, where he showed two paintings: Vue de Dieppe (View of Dieppe) and Lever de Lune (Moonrise). The summer of 1877 would be his last on his Botin; he returned from this journey to work on a large scale painting which he was not able to complete. Daubigny died on February 19, 1878 in Auvers-sur-Oise.

Zacharie Astruc, one of the staunchest supporters of the work of Edouard Manet, wrote of Daubigny that “He is the painter of simple impression. He is tender; he is sweet; he is captivating… he retains a delicious naiveté - simple as a child before his subject, adding nothing, removing nothing-strong of heart and yes; unpretentious by means of the truth; arriving by force of feeling and by ardor and by his penetrating passion for his art at a remarkable individuality.” (Fidell-Beaufort and Bailly-Herzberg, pg. 49) Daubigny’s career began in the atelier of an academic artist but progressed beyond the borders of this rigid training to become a symbol of inspiration for the coming movement of Impressionism. His support of the younger artists was unceasing and in his own work he remained true to the depiction of nature, meriting his association with the Barbizon group of landscape painters. Charles Daubigny, in his work and his life, became one of the key forces behind the introduction of new artistic movements while fighting his own battles for the acceptance of his work; one that was ahead of its time and misunderstood by many. It is only with hindsight that audiences can best appreciate the modern nature of Daubigny’s oeuvre with its commitment to independence and personal verve.

| AVAILABLE WORKS | |||