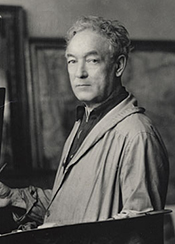

BIOGRAPHY - William Glackens (1870 - 1938)

William Glackens grew up in a family with deep roots in the Philadelphia region. The youngest of three children, Glackens was born on March 13, 1870 to Elizabeth Cartwright Finn Glackens and Samuel Glackens, who worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad. William's brother Louis, who would become an illustrator for Puck and Argosy magazines, was six years older and his sister Ada was barely a year older. Growing up at 3214 Samson Street, about a block from the Schuylkill River, the children all attended Northwestern school in the neighborhood. The boys then went on to study at Central High School, a progressive college preparatory school established in 1836. Of special note for Glackens was the drawing curriculum originally designed by Rembrandt Peale in 1840. He began his studies there in 1885 and received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1890. [i]. Among his classmates were John Sloan, who would soon become a good friend, and Albert C. Barnes, whose passion for collecting would later include purchasing many of his former classmate's works.

After graduating as the valedictorian of his class in February 1890, Glackens left Philadelphia to travel through Florida for a few months, perhaps sketching the tropical landscapes so different from his native region. By March 1891, however, he was employed as an "artist-reporter" for the Philadelphia Record. Illustrated newspapers had been popularized by Joseph Pulitzer shortly after he purchased the New York World in the spring of 1883, and publishers across the country quickly followed his example. By the time Glackens went to work as an illustrator, the job entailed a steady round of on-the-spot life drawing, in other words sketching news events as they happened or at the very least, shortly after they happened. Covering accidents, fires and floods was all part of the illustrator's daily activities.

In March 1892—just a year after first joining the staff of the Philadelphia Record—Glackens moved on to the Philadelphia Press. In 1893 Everett Shinn was also hired by the Press as an illustrator, followed by George Luks in 1894 and John Sloan in 1895. The core group of artists that would become known as the Ashcan School was gradually emerging from the staff of illustrators for Philadelphia newspapers. There can be no doubt that working as an illustrator honed Glackens' drawing skills as well as his awareness of the social conditions of his time.

During these years, Glackens and Sloan both decided to enroll in evening classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA). Sloan introduced Glackens to another of their classmates, Robert Henri, who had just returned from three years in Paris where he had studied at the Académie Julian and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. A little older and more experienced as a painter, Henri soon became the leader of the band of illustrators working for the Philadelphia press. They began to gather at Henri's studio on Walnut Street to discuss artistic ideas about Impressionism, Realism, and the relationship between traditional fine arts and design; they also enjoyed some reportedly raucous theatricals. [ii]

By 1894, Glackens shared a studio with Henri at 1717 Chestnut Street and prepared his painting The Brooklyn Bridge for the 64th annual exhibition at PAFA. That same year, he produced his first major series of illustrations for a book by George Nox McCain, Through the Great Campaign: with Hastings and his Spellbinders (Philadelphia: Historic Publishing Co. 1895). With these early signs of success as a professional artist, Glackens quit his job as a newspaper illustrator and set sail for France in June 1895 with Henri and fellow painters Elmer Schofield, Augustus Koopman, and Colin Campbell Cooper, as well as the sculptor Charles Grafly. Once settled in Paris, they began traveling to the Forest of Fontainebleau and other small towns in the Ile de France region on sketching trips as well as painting scenes of Parisian life in cafes, theatres, and the circus. In August, the group embarked on an ambitious bicycle trip to Brussels, Antwerp, The Hague, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam, where they explored the contemporary work of painters associated with The Hague School as well as the seventeenth-century art of Frans Hals and Rembrandt. Three months later, Glackens returned to Paris and rented a studio at 6 rue Boissonade in Montparnasse where he would remain for the next eighteen months.

The winter of 1895-96 was a productive one. Glackens created a painting that he hoped to submit to the annual Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in the spring. And he was among the first Americans to see the exhibition of the Caillebotte Bequest at the Musée du Luxembourg in February. The controversial bequest was announced in August 1895 when Caillebotte's final will was publicly announced, but it was not exhibited until six months later. Jean Bernac, an art journalist, described the official response to this bequest in the Art Journal.

"Just to think of it—Gustave Caillebotte, who was one of the primary combatants in the first Impressionist clan, had bequeathed to the State some sixty canvases, upon the base of which names were to be read that the members of the Institute never dared to pronounce without first making the sign of the cross! These were Manet, Degas, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro, Cézanne, without omitting Millet, who was represented by a drawing and one small watercolor." [iii]

Bernal went on to explain that the terms of the will stipulated that the paintings were to be hung in the Musée du Luxembourg and that they could not be taken down, put into storage, or sent to provincial museums. If the State refused to accept the bequest, then the paintings would be kept until the cultural officials saw the error of their decision. Glackens was very impressed with what he saw on the Luxembourg Museum walls, particularly with Edouard Manet's work. Likewise, the exhibition made a big impact on Henri. Both Americans understood that the Impressionist painters had created a new way of seeing the world and a new technique for representing daily life. It would change their work profoundly.

When Glackens returned to the US that fall, he settled in New York where he rented a studio in the Holbein Studio Building at 139 East Fifty-fifth Street. He had accepted a position as an illustrator at the New York World where his job was to draw comics; not surprisingly, he left as soon as possible to take a job as an artist-reporter with the New York Herald. However, in less than a year, he decided to try his hand as a freelance magazine illustrator. His first magazine illustrations were for "Slaves of the Lamp", a short story by Rudyard Kipling published in McClure's Magazine. In 1898, McClure's Magazine again hired Glackens, along with a news correspondent, to cover the Spanish-American War. The men traveled to Cuba where Glackens did at least 36 drawings, only twelve of which were published. [iv] Whether it was the experience of covering a war or Glackens' lack of interest in being an "artist-reporter", that was his last project for a daily newspaper.

Instead, he turned his attention to establishing a solid career as a magazine illustrator, working for many of the most renowned publications of his day. His clients included Century Magazine, Collier's Weekly, McClure's Magazine, Harper's Bazaar, Harper's Weekly, Saturday Evening Post, Scribners, and many smaller publishing companies. This work allowed Glackens to live comfortably and devote significant amounts of time to his painting.

The first group exhibition of the artists in Henri's circle was held in April 1901 at the Allan Gallery, 14 West Forty-fifth Street, New York. Together with Henri, Sloan, Alfred Maurer, Ernest Fuhr, and others, Glackens began his career as a modern painter in earnest. His work was well reviewed by Charles FitzGerald, the art critic for the New York Evening Sun. [v] The next exhibition, organized by Henri, opened at the National Arts Club on Gramercy Park in January 1904. Both Arthur B. Davies and Maurice Prendergast joined with Henri, Sloan, Luks, and Glackens to present their work. The artists, later known as "The Eight", were increasingly organizing as a group and presenting their ideas in the context of a modernist approach to their work.

Glackens' personal life was also evolving. He married a fellow-artist Edith Dimock (1876-1955) on February 16, 1904. Dimock was the daughter of a silk merchant in Connecticut, but she had taken an unconventional path by moving to Manhattan to study art as a young woman. Her progressive beliefs were manifested throughout her life; she joined the suffragists in advocating for women's right to vote. She continued to work as an artist after her marriage, even using her maiden name professionally. Shortly after the couple married, they moved to a new home at 3 Washington Square North in Greenwich Village.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, Greenwich Village was full of experimental writers, artists, actors, poets, playwrights, and musicians. It was fast becoming a bohemian enclave and attracting like-minded people from across the country. Edith and William Glackens settled easily into the congenial environment. And Glackens found that his painting was increasingly getting noticed. At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, he received a silver medal for painting and a bronze medal for his illustration work. The following year at the Carnegie Institute's annual exhibition, his painting Chez Mouquin received an honorable mention from a jury that included Thomas Eakins and J. Alden Weir.

In the spring of 1906, the Glackens set out on a belated honeymoon trip to Spain, followed by a stop in Paris in June and then on to London for the summer. Their son Ira was born the following year on July 4, 1907. Glackens' painting continued to evolve in response to the new ideas he absorbed in Europe and the work of his American colleagues in New York. After a disappointing rejection by the National Academy of Design in 1907, Glackens, Sloan and Henri began to plan another exhibition of their own. In February of 1908, the show opened at Macbeth Gallery, 450 Fifth Avenue, New York; in addition to their work, it included paintings by Davies, Luks, Prendergast, Shinn, and Ernest Lawson—"The Eight" as they would soon be called. The exhibition traveled to Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Newark, Toledo, Ohio, and Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Two years later, the group organized another independent exposition, this time including the work of Walt Kuhn as well. The Exhibition of Independent Artists opened in April at 29 West Thirty-fifth Street, New York; there was no jury and no prizes, a first in the history of American art. By December of 1909, the newly formed Association of American Painters and Sculptors held their first meeting to plan the International Exhibition of Modern Art (the Armory Show), scheduled to open in 1913. Glackens was a charter member as well as the chairman of the Committee on Domestic Exhibits.

On the eve of World War I, Glackens and Alfred Maurer made a buying trip to Paris on behalf of their old friend Albert Barnes, who was now a successful businessman and a doctor. Barnes had begun to create a collection of contemporary art, and his artist friends were only too happy to guide his selections. They returned from Paris in late February of 1912 with paintings by Manet, Degas, Renoir, Cézanne, van Gogh, Gauguin, and Matisse, most of which remain in the Barnes Foundation collection today.

Glackens' art was receiving increasing attention in these years as well. He had his first solo exhibition at the Folsom Art Gallery in March 1912, and by 1914, he had begun to paint full time. In 1917, there was another solo show, this time at the Daniel Gallery in New York. His activities as an advocate for modern art also evolved during the war years, culminating in his election as the first president of the Society of Independent Artists. The Society's first exhibition opened at Grand Central Palace in New York on April 10, 1917. [vi] Two years later, Glackens created illustrations for Roy Norton's short story "On the Beach" for Collier's Weekly; this was the last time he would produce illustrations. From this time forward, he worked as a full-time painter and was successful enough to move the family, which now included a four-year-old daughter Lenna, to a new home at 10 West Ninth Street. For the most part, the Glackens spent their summers in the resort towns of New England, often gathering with the growing families of other members of "The Eight" to enjoy the beaches and boating activities along the eastern seaboard.

Glackens' life in the 1920s was full of travel and considerable success. Winning the Temple Gold Medal at PAFA's 1924 exhibition was a particular honor. His painting, entitled simply Nude, demonstrated Renoir and Matisse's importance as inspiration and Glackens' ability to transform those influences into his own individual style. In winning the Temple Gold Medal, he joined an illustrious group of previous recipients such as Thomas Eakins, James McNeill Whistler, George Inness, John Singer Sargent, and Winslow Homer. [vii] The following year, he would begin working with C. W. Kraushaar Art Galleries in New York, where he would routinely have a solo exhibition about every four years. [viii]

Throughout the 1920s, Glackens traveled extensively in Europe, primarily France. He often spent the winter in the Vence at the villa called Les Pivoines and the summer in the region around Paris. In 1926, he toured Italy, ranging from Pompeii to Venice. It was not until October of 1931 that he returned to New York for more than a few months at a time. During the 1930s, he focused more on traveling in the US and Canada, although he continued to spend at least a month or two in southern France. In 1937, he won the Grand Prix for his painting Central Park, Winter at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris.

The following spring, Glackens was visiting his friends Charles and Eugenia Prendergast at their home in Westport, Connecticut when he died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage on May 22, 1938. A posthumous exhibition was quickly organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Carnegie Institute. A smaller version of the show traveled to Chicago, San Francisco, St. Louis, Louisville, Cleveland, Washington DC, and Norfolk, Virginia until March of 1940.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts

Akron Art Museum, Ohio

Art Institute of Chicago

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Ball State Museum of Art, Muncie, Indiana

Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine

Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia

Cleveland Museum of Art

Currier Gallery of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Detroit Institute of Arts

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Huntington Library, Pasadena, California

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

San Diego Museum of Art

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago

Wichita Museum of Art, Kansas

Notes

[i] Central High School in Philadelphia is the second oldest continuously operational public school in the country, and the only high school in the US with the authority (granted by an Act of Assembly in 1849) to confer academic degrees on its students. Those who complete the advanced program receive a Bachelor of Arts degree in addition to a high school diploma. In the twenty-first century, it continues to maintain a reputation for excellence in education and boasts of a very long list of distinguished alumni in business, government and the arts. For more information, see: https://centralhighalumni.com/the-history-of-central-high-school/

[ii] William H. Gerdts, William Glackens, Life and Work (New York: Abbeville Press in association with the Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, 1996) 10-25. Exhibition catalogue.

[iii] Jean Bernac, “The Caillebotte Bequest to the Luxembourg”, Art Journal, August 1895 (230-232).

[iv] Gerdts, 265.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Grand Central Palace in 1917 was located between Forty-sixth and Forty-seventh Streets in Manhattan next to Grand Central Station. Designed by the architectural team of Warren & Wetmore and Reed & Stem, the building provided the largest exhibition halls in New York from 1911 to 1953, when the IRS took over the exhibition space for its offices.

[vii] The Temple Gold Medal was sponsored by Joseph E. Temple (1811-1880), a Philadelphia businessman and PAFA board member. Although Temple's intention was to have the medal awarded to the "best painting" at the annual PAFA exhibition, the juries were erratically inconsistent. Because of the jury's inability to agree on anything, the award became an object of much humor among artists. Thomas Eakins reportedly took his gold medal to the Philadelphia Mint to have it melted down for its value in gold. It was not until 1900 that PAFA decided that only one painting would be honored each year and that the subject of that painting was not restricted to any one category. By the time that Glackens was awarded the medal in 1924, it was a respected and legitimate honor. For more information, see Mark Thistlethwaite, "Patronage Gone Awry: The 1883 Temple Competition of Historical Paintings," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 112, no. 4 (October 1988) 545-78.

[viii] Glackens' solo shows at Krauthaar Art Galleries occurred in 1925, 1928, 1931 and 1935. See Gerdts, 267.