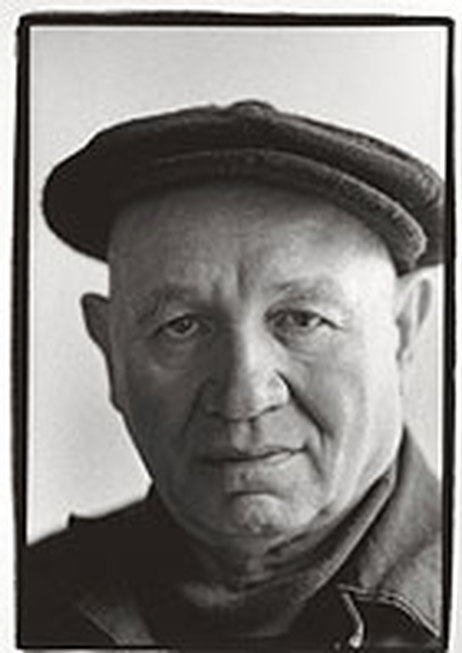

BIOGRAPHY - Romare Bearden (1911 - 1988)

The circumstances around Romare Bearden’s birth date are somewhat uncertain. There is documentation that indicates two different years, 1911 and 1912, as his birth year: first is a “delayed Certificate of Birth Registration” registered in Charlotte, North Carolina but not filed March 1949, and second is a baptismal record at the Episcopal Church of St. Michael’s and All Angels, also in Charlotte. Art historians generally accept the church baptism as most likely to be correct since the church would have been directly involved with the Bearden family. If so, the young Bearden’s birthday was 19 November 1911. Regardless of the year, Romare Bearden was born to Richard Howard and Bessye Bearden, a middle-class African-American couple. Both of Bearden’s grandparents were property owners, in North Carolina and in Pittsburgh; and both of his parents had attended college. For African-Americans in the early twentieth century, this was relatively unusual, especially in the American south where Jim Crow laws made life increasingly difficult.

Largely in response to the repressive culture of the south, the Beardens moved to Harlem in 1914. There, they settled at 154 West 131st Street, and were soon active members of the community. Bearden’s father, who was known by his middle name, Howard, worked as a sanitation inspector for the New York Health Department, and reportedly was something of a storyteller in the neighborhood. He was also a pianist, which helped to shape his son’s lifelong involvement with music. Bessye Bearden was more of a social activist, working as the New York correspondent for the Chicago Defender, one of the most influential African-American newspapers in the country.

During Bearden’s youth, Harlem was a center of cultural and social ferment. His parent’s circle of friends included writers such as Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and George Schuyler; musicians such as Duke Ellington and Fats Waller; the actor and activist Paul Robeson; and W. E. B. Du Bois, one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as Mary McLeod Bethune, the founder of the National Council of Negro Women and a vice-president of the NAACP. Growing up among such gifted artists and activists, the young Bearden absorbed abundant lessons in the arts and social activism.

He received his basic education was at the New York City public schools, although he also spent some of his high school years living with his maternal grandparents, Carrie and George Banks, in Pittsburgh. The Banks ran a boarding house, and their grandson reportedly soaked up many stories from the conversation of boarders around the dinner table. This characteristic penchant for collecting tales from the people in his environment will later emerge in Bearden’s artwork.

Bearden’s college years was somewhat peripatetic, beginning at Lincoln University near Philadelphia in 1929, then moving to Boston University from 1930-32; and finally concluding at New York University (NYU) from 1932-35, where he received his bachelor’s degree in education in 1935. Although for many years Bearden denied that he had studied art, perhaps in deference to his mother’s wishes that he focus on learning a profession, he was in fact actively involved in both writing articles and drawing cartoons for NYU’s monthly publication, The Medley, serving as its Art Editor in 1934. During his university years, he also designed several magazine covers for Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, the National Urban League publication, and wrote an essay on “The Negro Artist and Modern Art” for the December 1934 issue.

Cartooning was an early fascination for Bearden. He studied the history of cartoons during his NYU career, even publishing an extensive article on it in The Medley in 1934. Professionally, he began drawing cartoons for W.E. B Du Bois’s publication, Crisis in 1934, and then editorial cartoons for the Baltimore-based weekly, Afro-American, from September 1935 through May 1937.

During the early 1930s, Bearden also studied with the exiled German Dadaist, George Grosz, who was then teaching at the Art Students League in New York. Enrolment records indicate that Bearden took a drawing class from Grosz in 1933 and a life class in 1935. The influence of Grosz, however, can be seen in many of Bearden’s later collage paintings, and perhaps also in his understanding that art combined with activism can be powerful elements of social change.

After graduating from NYU in 1935, Bearden found a job with the New York Department of Social Services, where he was assigned to collect insights on the Depression. Like many other government-sponsored documentation projects, this one provided a detailed record of the effects of the Depression on ordinary people. Back home in Harlem, Bearden also continued his involvement in the community, participating in a variety of art-related activities with the Harlem Artists Guild, the 137th St YMCA, the Harlem Community Art Center, and the Harlem Art Workshop at the public library’ on 135th Street.

Perhaps the most important influence of these years was the informal group of artists known as “306.” The name referred to 306 West 141st Street where the first floor of a three-story converted stable building served as a gallery and gathering place for a multi-generational and cross-disciplinary group of artists. At the heart of this group were three men: painter Charles “Spinky” Alston; sculptor Henry Bannarn; and dancer and cabinetmaker Addison Bates. Other visual artists involved with “306” included painters Ernest Crichlow, Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, and printmaker Robert Blackburn. Writers included William Attsway, Ralph Ellison Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, William Saroyan, and the brothers Arthur and William Steig. In short, this group represented several generations of Harlem Renaissance artists, all of whom gathered at “306” to exhibit their work, share ideas, and no doubt discuss the ups and downs of the art world.

Bearden’s first solo show occurred in May 1940 at “306”. It included seven oil paintings, six gouaches, five watercolors, and six drawings. Works such as Soup Kitchen, 1937, proclaimed his artistic roots in the realist movement of the nineteenth century, but also remained solidly grounded in the context of Depression-era social concerns. Shortly after this exhibition, Bearden rented a studio (for $8.00 per month) at 33 West 125th Street where Jacob Lawrence, and the writers Attsway and McKay, also worked. This was his first venture into having a separate studio of his own, and it reflects the seriousness with which he was building his career as a painter.

Another turning point during the early 1940s was Bearden’s visit to North Carolina and Atlanta. Although there are no documented sketches or paintings from the trip, Bearden’s art changed noticeably after his return. He began a series of images depicting the life of Christ in large-format gouaches painted in an increasingly abstract style. The earliest of these works are developed in an “abstracted” social realism style with the biblical subject matter cloaked in scenes of everyday life. The Visitation, 1941, for example, might simply be an image of two women talking, but the title and the gesture of one woman reaching out toward the other’s abdomen clearly implies the traditional story of the meeting between the Virgin Mary and Elizabeth.

All artistic exploration came to an abrupt end with the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941; Bearden entered the Army and spent the next few years working at various locations throughout the U.S. These years were also marked by the unexpected death of his mother, Bessye, from pneumonia in 1943. Just a year later, his fortunes changed for the better when he met Caresse Crosby, the co-founder of the Paris-based Black Sun Press that had published authors like James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence and Hart Crane in the 1920s. By 1944, Crosby and her business partner, David Porter, operated the G Place Gallery in Washington, D. C. where Bearden had his first solo exhibition outside of Harlem. This exhibition, which ran from mid-February to early-March, was entitled Ten Hierographic Paintings by Sgt. Romare Bearden—and it brought the painter his first modest financial success.

A year later, in June 1945, Bearden’s second show at G Place Gallery earned him even more attention when he exhibited a series of watercolors based on the gospels of Matthew and Mark, as well as the Passion of Christ. As a result of this exhibition, he met the New York art dealer, Samuel M. Kootz, whose gallery at 15 East 57th Street became the second venue for the Passion of Christ watercolors in the autumn of 1945. These abstracted representational images were well received in New York’s art-buying circles; the Museum of Modern Art purchased a watercolor entitled He is Arisen, and several private collectors acquired multiple pieces. In short, Romare Bearden had become the “new find” of the late 1940s art world in New York.

Not surprisingly, the next few years were filled with consistent work and steady exhibitions at Kootz’s gallery. Although Bearden returned to work at the Department of Social Services after his demobilization, he nonetheless found time to explore his increasingly abstract style in three painted narratives: in 1946, he created Lament for a Bullfighter based on a 1935 poem by Federico Garcia Lorca; in 1947, Gargantua and Pantagruel based on the François Rabelais tales from 1532-64; and 1948, The Iliad derived from Homer’s 8th century BCE epic poem. All were heroic narratives that Bearden transformed into visual epics. Unfortunately, the relationship with Kootz came to a sudden end in 1948 when the dealer closed his gallery briefly, only to re-open it in 1949 as a venue exclusively for abstract expressionists. For Bearden, this meant that he was no longer welcome in the “downtown” world of New York’s art community.

The full force of this racism, and the fickleness of the art world, led Bearden—as it had so many other African-Americans of earlier generations—to head for France. In 1950, he studied at Institut Britannique and the Sorbonne, living at 5 rue des Feuillantines in the 5th arrondissement where $40 month paid for a studio and three meals a day. There, he met the writer Albert Murray, a fellow American who became a lifelong friend; and he became part of the multi-cultural, multi-national arts community that was Paris in 1950s. For Bearden, Paris was transformative in the same way that it had been for other African-Americans; the openness of the city was legendary, but the lack of apartheid laws (and practices) was unprecedented in the African-American experience. For the rest of his life, Bearden would return periodically.

When he came back to Harlem, Bearden moved in with his father, worked at his social services job, and even wrote some songs for Billy Eckstine and Billie Holiday. What he doesn’t seem to have done was paint. This period in his life is vague; there is little documentation of his activities, and even less evidence of any painting. However, he did meet Nanette Rohan, who became his wife in 1954. After their marriage, the newlyweds continued to live with Bearden’s father.

Marriage (or Nanette) seems to have encouraged Bearden to resume painting more regularly, and in 1955, he was once again exhibiting his work, this time at the Barone Gallery. That same year, he also began studying with Mr. Wu, a Chinese calligrapher who introduced him to Chinese landscape painting, and spurred an interest in Zen Buddhism. Despite this propitious resumption of his art, Bearden experienced an emotional breakdown in 1956. The reasons for this are unclear, but shortly thereafter, Bearden and Nanette moved into their own place at 357 Canal Street where they could enjoy more privacy. They remained there for the rest of their lives. After the move, Bearden began exploring the potential of collage. His 1956 painting, Harlequin, consists of a collage of papers, paint, ink and graphite—an exercise in bright colors, abstracted commedia del’arte imagery, and perhaps an homage to the early twentieth century work by Pablo Picasso, Joan Miro or even Jean Cocteau. Most importantly, it hints at the direction that Bearden’s work will take in the early 1960s.

The decade of the 1960s was an era of profound social, cultural and political change in the United States. For Bearden, the 1960s began with a successful solo exhibition at the Michel Warren Gallery, from which the Museum of Modern Art purchased another of his oil paintings, Silent Valley of the Sunrise, 1959. In 1961, the re-named Daniel Cordier & Michel Warren, Inc. gallery again showed his work with notably successful results. With a little extra money from art sales, Bearden and Nanette make an extended trip to France, Italy and Switzerland where he could study the old masters, and by 1963, he had returned to painting in a figurative style—based in part on his studies in Europe. In addition, collage techniques began to appear as a significant element in his artwork.

By the summer of 1963, the Civil Rights Movement was front-page news, and Bearden’s studio was the center of an alliance of African-American artists who gathered there to determine “what should be their attitudes and commitments as Negro artists in the present struggle for Civil Rights.” [i] The name of the organization was Spiral; and in addition to advocating for fuller representation of African-American artists in the galleries and museums of New York, Spiral also sponsored exhibitions beginning in 1965. Their goal was to depict the lives of African-Americans in both daily activities and in the struggle for equality and social justice under the law.

Bearden’s work from the 1960s focused on depicting the African-American experience, using his collage technique to capture imagery from magazines and newspapers. Beginning in 1964, he created what he called “projections” which were photostat enlargements of his collage paintings. These black and white images have the curiously matte quality typical of photostats, but they also create starkly silhouetted forms that tend to emphasize different visual perceptions than the original color collage versions. In his first solo museum show at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C. in 1965, Bearden exhibited his collage paintings side by side with the “projection” related to each one, thus highlighting the differences that appear when viewers see the image—or the world—only in black and white.

In 1965, Bearden started making site-specific collages beginning with a series rooted in his memories of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina and Pittsburgh. These paintings reflect a shift from the use of cut out magazine images to the incorporation of torn or cut colored sheets of paper. Over the next few years, the fragments of colored paper became more and more dominant, often interleaved with paint and graphite.

By the end of the 1960s, Bearden was at last able to leave his ‘day job’ at the Department of Social Services, and devote his attention full time to his art. Ironically, this coincided with the infamously arrogant exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art entitled Harlem on My Mind: The Cultural Capital of Black America 1900-1968 which failed to include any African-American artists in the show. For Bearden and his colleagues, this was entirely in keeping with the historical disregard that New York museums displayed in relation to African-American artists—including the Museum of Modern Art’s time honored failure to include them in any of their regularly scheduled Americans exhibitions.

Although Bearden himself had organized two exhibitions of African-American art earlier in the decade, he now undertook the creation of a permanent gallery in partnership with Norman Lewis and Ernest Crichlow. Together, they founded Cinque Gallery as a showcase for young artists; the gallery still exists today. It must be noted that Bearden’s curatorial activities also led him to study—and to co-author—the art history of African-American artists. Since there was virtually no formal scholarship on the topic when Bearden began his investigations in the mid-60s, he partnered with writer Harry Henderson to develop detailed documentation on the biographies of significant African-American artists. The book, A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present was completed in 1970s, but not published until1993. It remains an important foundation text for both art history and African-American studies.

The decade of the 1970s was especially productive. With financial security and the freedom to commit his time fully to his art, Bearden expanded his aesthetic horizons once again to encompass very large scale, multimedia creations. Most famous is his series of six connected fiberboard panels (4 x 18’) known as The Block. This 1971 piece included not only imagery depicting life on a block in Harlem, but also the recorded sounds of street noises, newscasts, and church music. When The Block was exhibited in Berkeley, California as part of a traveling exhibition sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art, it was so popular that the City of Berkeley commissioned Bearden to design something similar for them. The result was Berkeley—The City and its People, a monumental collage of paint, ink, and graphite on seven fiberboard panels measuring 10.5 x 16’ when completed. A year later, New York City followed Berkeley’s example, and commissioned a work for the Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center in the Bronx. The result was considerably less positive; Bronx City Councilman Ramon Valez declared in the New York Daily News that the piece was … “too obscene and not relevant enough…a piece of junk that is not worth anything…done without any community involvement.” [ii] The piece was moved to a warehouse immediately, and remained there until 1983 when it was installed at Bellevue Hospital.

In spite of the occasional controversy, the 1970s seem to have been both productive and happy. Bearden and Nanette spent considerable time on the Caribbean island of St. Martin where Nanette’s ancestors had lived; and in 1973, they were able to build a home of their own there. Caribbean influences and imagery emerge in Bearden’s work almost immediately as he studied the customs and spiritual traditions brought from Africa to the islands as part of the slave trade.

Back in New York, he continued to exhibit his work at Cordier and Eckstom, the same gallery that had taken him on as part of their “stable” in the 1950s. Increasingly, the painting collages of the 1970s emphasized musical themes. From the urban blues clubs in Kansas City and New York to the down-home blues of Mecklenburg County churches and dancehalls, Bearden’s collages portrayed a swirl of color and motion that mimicked the music itself. During this time, he was also designing costumes and sets for Nanette’s Contemporary Chamber Dance Group and for the Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre, thus reinforcing the connection between music, visual art and dance in yet another medium.

Rearden’s last years were filled with many honors including a White House reception hosted by President Jimmy Carter in 1980. He also received the Freedom Fighter Award from Atlanta Chapter of NAACP, and the Frederick Douglass medal from New York Chapter of National Urban League, both in 1978.

By 1982, Bearden’s health was starting to fail, and although he continued working up until shortly before his death, he was increasingly ill with bone cancer. He died in New York Hospital on 12 March 1988.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

Arizona State University Art Museum, Tempe, Arizona

Art Institute of Chicago

Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois

Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine

Brauer Museum of Art, Valparaiso University, Valparaiso, Indiana

Brooklyn Museum, New York

Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Connecticut

Cameron Art Museum, Wilmington, North Carolina

Canton Museum of Art, Canton, Ohio

Clay Center for the Arts and Sciences, Charleston, West Virginia

Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, California

Dallas Museum of Art

Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa

Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma

Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, South Carolina

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D. C.

Howard University Art Collection, Washington, D. C.

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, Indiana

Indianapolis Museum of Art

Jersey City Museum, Jersey City, New Jersey

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri

Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, Wisconsin

Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Milwaukee Art Museum

Museum of Modern Art, New York

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina

Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando, Florida

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia

Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D. C.

Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

[i] Ruth Fine, The Art of Romare Bearden, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 2003) 28. Quoted from Jeanne Siegel’s “Why Spiral?” Art News 65 (September 1966):48.

[ii] “Hospital Art Wasting Away in Warehouses” New York Daily News, October 22, 1976, 4.