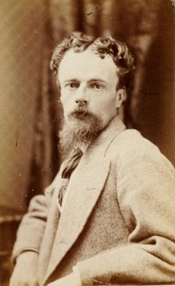

In the nineteenth century, the city of Leeds was the center of England’s thriving wool industry. The river and canal system known as the Aire and Calder Navigation had opened in 1699 and expanded regularly throughout the 1700s, thus positioning Leeds to become a leading center of the industrial revolution in Great Britain. It was into this prosperous, albeit gritty, environment that John Atkinson Grimshaw was born on September 6, 1936 to David and Mary (Atkinson) Grimshaw. His father is said to have served as a police officer, although it should be noted that the urban British police forces outside of London were not established until 1835. This suggests that David Grimshaw may have been part of the very first group of policemen in the city of Leeds. He remained in that position until 1842, when he moved his family, now with four sons, to Norwich where he worked for Pickfords, a hauling company that was pioneering the use of the railway system to transport household goods.

The Grimshaw boys were enrolled in King Edward VI School, an independent day school with a pedigree that can be traced back to 1096 when it was founded by the first Bishop of Norwich. During the years when Grimshaw attended, the traditional classical studies that had earned the school its academic reputation were being supplemented by courses that related to the industrialization that was sweeping through Europe. Of particular note is that a number of the artists associated with the Norwich School of Painters also studied at King Edward VI School, including John Crome (1768-1821) who taught there in the early 1800s. Although Grimshaw is typically understood as a self-taught painter, it seems likely that he received some form of art education during his six years at the school.

In 1848, the family returned to Leeds. David Grimshaw opened a grocery in Brunswick Row, not far from the central market square, and also worked for the railway; it is probable that Mary Grimshaw was the primary manager of the grocery with the assistance of her sons. At age sixteen, John Atkinson Grimshaw followed his father into the railway business, working as a clerk for the Great Northern Railway. During this time, he also began to paint from nature in the parks and open fields surrounding the city.

Grimshaw’s earliest works are drawings of individual plants, birds and nests; these were followed by detailed landscapes. He spent his free time drawing and painting from nature and reading widely about contemporary art developments, in particular the writings of John Ruskin (1819-1900) whose Academy Notes offered commentaries on the Royal Academy exhibitions during the late 1850s. [i] Ruskin’s support of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood undoubtedly drew young Grimshaw’s attention to the work of painters like William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, whose attention to detailed landscape textures may have served as his inspiration. Gradually, his work grew more sophisticated and more confident, eventually leading Grimshaw to consider the possibility of becoming a full-time painter.

In 1858, however, he married his cousin Frances (Fanny) Theodosia Hubbarde (1835-1917) and settled into a home in New Wortley, Leeds, which was then the neighborhood surrounding the city’s largest gasworks. Shortly after his marriage, Grimshaw began to sell his paintings to a local bookseller, Mr. Fenteman, and by 1861, he had quit his railway job to become a full-time painter. His first exhibition was in 1862 at Newton Brothers in Park Lane, Leeds. [ii] His second was at the Leeds Philosophical Hall, where he showed six paintings in December and reportedly sold a couple of them.

Throughout the 1860s, Grimshaw continued to develop his skills, and traveled the region to paint the diverse landscapes of Yorkshire and the Lake District, often taking Fanny along to serve as a model. By 1863, the young couple were able to move out of New Wortley to the Woodhouse Ridge neighborhood of Leeds, an area that offered a haven of wooded green spaces within the city—and a much healthier environment in which to raise a family. Although reports vary widely as to the number of children that the Grimshaws had (fifteen or sixteen seems to be likely), it is certain that only six of them survived to adulthood.

Grimshaw was also interested in photography, which he used as an aide-mémoire for his compositions during the first decade of his life as a painter. The 1865 painting, Nab Scar, illustrates the process clearly: Atkinson not only took his own photographs of this Lake District mountain, but he also owned a photograph of the site by Thomas Ogle of Penrith from ca. 1864. The compositions of the two are nearly identical. [iii] Grimshaw made no secret of his use of photography as other painters often did, but he does seem to have stopped using it sometime in the later 1860s. This newfound confidence in relying on his own compositional skills coincided with a burst of activity in both sales and aesthetic experimentation.

His first major regional exposure occurred in 1866 when a still-life titled Apples was included in the exhibition at the Royal Institution in Manchester; in 1868, he sold a number of paintings during a trip to London; and in 1869, five of his canvases were included in an exhibition at the Leeds Mechanics’ Institute Picture Gallery, the precursor to today’s Leeds City Art Gallery. Grimshaw’s success during these years mirrors the growing prosperity and power of Leeds’ industrialists. Like many Victorian businessmen, the wool merchants, railway barons, textile mill owners and shipping magnates of Leeds strove to establish their cultural legitimacy by supporting the arts, and ultimately by creating the museums and libraries that now house the extensive collections of Victorian art. Grimshaw was both a recipient and a producer of the benefits of this new industrial society.

In terms of aesthetic development, the late 1860s were equally productive. Grimshaw began to develop his own individual style, painting his first moonlit scene, Whitby Harbour by Moonlight, in 1867 and experimenting with images of docks and dimly lit industrial streets. During this period, he and Fanny converted to Catholicism, although why they made this decision is not known. A Catholic revival had surfaced in several parts of Europe in the nineteenth century, and certainly, many members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were firmly grounded in either Roman Catholicism or the Anglo-Catholicism that emerged from Oxford University in the 1830s. Likewise, earlier Romantic artists had associated Catholicism with a perceived “golden age” of medieval virtue, a time period that fascinated both Grimshaw and the Pre-Raphaelites. The most noticeable example of this was A.W.N. Pugin’s gothic revival design for the Houses of Parliament in 1836. As the construction of the new Parliament building drew to a close in the late 1860s, the press coverage of the rationale behind the design and the belief that Catholicism (and presumably a medieval Catholic architectural design vocabulary) nurtured a more Christian society undoubtedly spurred conservation throughout the kingdom. [v] In short, there were ample societal sources for the Grimshaw’s conversion to Catholicism in addition to the whatever personal issues may have been involved.

As the decade of the 1870s opened, life looked very promising for the Grimshaw family. The respected London fine arts dealer, Thomas Agnew & Sons, was actively promoting the work of contemporary British painters, including Grimshaw; this meant a reasonably steady income and a growing list of private collectors who admired his art. In addition, he regularly participated in London exhibitions, debuting at the Royal Academy in 1874 with the painting, The Lady of the Lea.

In his personal life, Grimshaw moved his ever-growing family to Knostrop Hall, a seventeenth century manor house along the Aire River east of Leeds. The picturesque mansion, which he painted frequently, appealed to Grimshaw’s love of romanticized imagery; a composition signed and dated 1870 shows the Hall through a misty landscape of barren and fallen trees, suggesting an illusionary vision rather than a concrete, earth-bound residence. This propensity for medievalizing romanticism remains strong in Grimshaw’s work during this period, linking him both to the Pre-Raphaelites and to the later generation of Symbolist artists who built on the romantic foundations of the early nineteenth century.

Grimshaw’s reputation expanded significantly during the 1870s. He was well known and respected in Leeds, and increasingly, he was seen as a legitimate contemporary of London painters like James Tissot and Laurence Alma-Tadema. Not surprisingly, he painted a series of fashionable society women in 1875-76 that was compared to those of his colleagues. Most of Grimshaw’s women, however, are far more meditative and moody than the Victorian tableaux models seen in the work of Alma-Tadema or Frederick Leighton. These tonal paintings, such as A Classical Maiden, 1870s, show the influence of Japonisme and very likely James McNeill Whistler, who would later become a personal friend.

In 1876, Grimshaw moved his family again, this time to the Scarborough where it was thought that the air would be healthier. The Grimshaws had lost three of their children to diphtheria in Leeds and the hope was that the sea breezes in Scarborough would offer a less dangerous environment. [vi] The new residence, which was leased from Grimshaw’s patron Thomas Jarvis, was called Castle-by-the-Sea; again this was a fantastical structure, built to resemble a fictional castle on the Rhine as described in a poem by the German romantic writer, Johann Ludwig Uhland (1787-1862). The Englishmen, however, knew the poem through a translation made by the American poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882). Such a cross-cultural exchange was indicative of the increasingly international world of the late nineteenth century.

Grimshaw made what seems to have been his first trip abroad in 1878 when he escorted his children’s governess back to her home in Germany. During the course of the journey, he also traveled through France, where he likely had a chance to visit friends and colleagues in Paris—and to see the galleries and museums. Back home in Scarborough, Anna Leefe was hired to serve as governess, but also as Grimshaw’s studio assistant and model. She remained with the family for many years and appears in many of Grimshaw’s paintings from the 1880s and 1890s. One of them, The Chorale, 1878, serves as a personal manifesto for Grimshaw’s aesthetic at this time. The setting is a drawing room at Castle-by-the-Sea where Leefe is shown playing a pianoforte. Unlike some of Grimshaw’s earlier female figures, Leefe is more fully detailed and realistic, perhaps because he now had the luxury of having a model who was readily available when needed. Key to the aesthetic, though, is the very modern design of the room: the influence of Japonisme is obvious in the blue and white porcelain framing the piano and the fans flanking heraldic metal chargers on the chair rail. Orientalist Persian carpets define the floor, and what appears to be a Moorish textile is draped over a traditional chair bearing one of the distinctive symbols of the Aesthetic Movement on its seat—an embroidered peacock. Perhaps most distinctive is the willow pattern wallpaper, so clearly a reference to the hand-crafted work of Pre-Raphaelite designer and theorist, William Morris (1834-1896). Taken as a whole, this painting speaks of Grimshaw’s whole-hearted embrace of the concept of a totally designed environment that Morris articulated in both his work and his writing.

The idyll that was life at Castle-by-the-Sea came to an abrupt end in 1879 when financial disaster struck Grimshaw in the form a faithless friend who failed to honor his pecuniary obligations to pay back a substantial loan. Grimshaw was left with a large debt that he now had to repay. The family returned to Knostrop in Leeds and Grimshaw rented a studio in Chelsea, London. There he was able to work consistently and without interruptions; fortunately for Grimshaw, his work continued to be popular and his sales were satisfactory. The Royal Academy accepted Endymion on Mount Latmus in 1880 and the gallery of Arthur Tooth and Sons was now exhibiting his work. The moonlight scenes of London proved very successful with the art collecting public as did other cityscapes of the Thames and the waterfront. These years in London were also marked by a close friendship with Whistler.

During the 1880s, Grimshaw’s focus shifted to a broader variety of urban images, often documenting the grittier, more industrial areas of London or Leeds. The moonlit reveries were now often set in the back streets of warehouse districts or in the shadows of looming bridges. Even the compositions set in more prosperous neighborhoods often display a subdued atmosphere as solitary figures wander along walled roads on foggy evenings. In these canvases, Grimshaw transforms the mundane world of commerce and industrialization into evocative imagery, demonstrating not the desire for a return to a make-believe medieval world, but an embrace of the reality of modern life. He had moved from a romanticized version of the past to the realization that the world in which he actually lived was a valid, and perhaps more important, subject for art.

Having paid off his financial obligations by the mid-1880s, Grimshaw felt comfortable returning full-time to his home at Knostrop and to his studio there. The Royal Academy continued to exhibit his work annually, showing Salthouse Dock, Liverpool and Dulce Domum (Sweet Home) in 1885, and Iris in 1886; he was also showing paintings at Grosvenor Gallery as well as Arthur Tooth and Sons in London. American art collectors discovered his work in these years as well, providing yet another steady market for his paintings.

Grimshaw stopped painting in 1890, however, when Anna Leefe died of tuberculosis at Knostrop. Although there is very little information about the relationship between Grimshaw and his model/studio assistant, he did not paint again until 1892, which suggests that he must have been deeply grieved by her death. When he did begin to paint again, now with his son Louis as his assistant, the canvases were smaller, brighter in tonality, and elegantly abstracted. Clearly, Grimshaw continued to evolve as an artist throughout his life, moving from the simple nature studies of his youth to sophisticated and very modern expressive images in the 1890s. He died of cancer on October 31, 1893, at age fifty-seven, leaving behind four children, Arthur, Louis and Wilfred and Elaine, all of whom would become painters in their own right.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford, Oxfordshire

Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, Bradford, West Yorkshire

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, Yorkshire

Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool, Lancashire

Guildhall Art Gallery, London

Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, Lancashire

The Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefied, West Yorkshire

Kirklees Museums and Galleries

Laing Art Gallery

Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Museum of Gloucester, Gloucestershire

National Trust, The Lake District, England

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, NJ

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE

Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds Museums and Galleries, England

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, MN

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, Bournemouth, Dorset

Scarborough Art Gallery, Scarborough, North Yorkshire

Shipley Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne

Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds

Tate Britain, London

Victoria Gallery & Museum, Liverpool

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Whitby Museum, Whitby, North Yorkshire

[i] John Ruskin, The Works of John Ruskin, Volume 14, Part 1, editors Edward Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (London: George Allen, 1903).

[ii] David Bromfield and Alexander Robinson, Atkinson Grimshaw, 1836-1893, Leeds City Art Gallery ex. cat. (Ilkey, West Yorkshire: The Scholar Press, 1979-80) 3.

[iii] Richard Green Galleries, John Atkinson Grminshaw, 1836-Leeds-1893 (London: Richard Green in association with Leeds Art Gallery, 1998) Cat. no. 1.

[iv] Historically, Leeds was about 20% Catholic, in comparison with a 3-4% Catholic population in southern England.

[v] The concept that our built environment can shape our behavior was at the heart of Pugin’s theory, and although his application of it may now seem somewhat ingenuous, it is nonetheless one of the first manifestations of what will eventually become modernism in the hands of William Morris and Philip Webb in 1860. See Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, Contrasts: or, A parallel between the noble edifices of the Middle Ages, and corresponding buildings of the present day (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013). Originally published in London by Dolman, 1841.

[vi] Diphtheria is a bacterial disease that was greatly exacerbated by the poor air quality in industrial Britain. Half of the people who contracted it died. A vaccine was not developed until the 1920s. See the Center for Disease Control at: https://www.cdc.gov/diphtheria/about/index.html