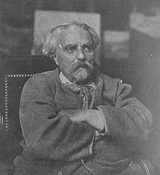

BIOGRAPHY - Jean F. Chaigneau (1830 - 1906)

In Camille Mauclair’s 1905 article dedicated to Jean-Ferdinand Chaigneau in L’Art Décoratif (Vol. 7:2, pages 40-46), Mauclair spoke of Chaigneau and his fellow Barbizon compatriots in a moralistic tone, lamenting the inevitable close of this important chapter in the history of nineteenth-century French landscape art. Chaigneau was effectively the last surviving member of the Barbizon group, a loose, but nevertheless significant group of artists who sought to elevate landscape and animal painting to a position of importance in French painting, representing an unidealized representation of the landscape in which they took refuge. For Mauclair, the simplicity of the Barbizon artists’ daily existence, and their perpetual unity with nature, symbolized the true artist working not for the patron, not for the Academy, but simply for the beauty and reverence in nature. Mauclair believed that (pg. 41):

The unity of thought and technique, the communion in the love of nature, an absolute disinterestedness, the contempt for career advantages, the passion of independence and the veritable morality of the artist, these are the traits of these admirable and modest foresters who have given to France her Ruysdaels, her Hobbemas, her Van Goyens, her Wynants, her Van der Meers, in the person of…Ferdinand Chaigneau...

Little did Mauclair realize that the following year, the remaining member of the group of which he spoke with such extreme and honest reverence, would pass away. Mauclair’s sensitive essay on Chaigneau and the artist’s relationship with the Barbizon group offers a glimpse into the importance of these disciples of nature for their ability to recognize nature’s offerings and by introducing them into nineteenth-century French art. Chaigneau continued these important traditions and brought them to the attention of the twentieth century audiences and writers, such as Mauclair, to look back upon these advances with favor and admiration.

Jean-Ferdinand Chaigneau was born on March 6th, 1830 in Bordeaux, France. His parents, Victorine Goethals and Jean-Frederic Marius Chaigneau were customs assistants, and thus by profession were not affiliated with the arts. Jean-Ferdinand was raised largely by his grandfather, however, Jean Goethals, a collector and founder of the Museum of Public Instruction.

In 1845, Chaigneau entered the École Gratuite de Dessin de Bordeaux, or the Free School of Drawing at Bordeaux, under the directorship of Jean-Paul Alaux, a painter who worked primarily with historical narrative scenes and landscape painting. William-Adolphe Bouguereau was also studying at this school at Bordeaux at this time – he had begun a few years before Chaigneau - but the comparison between the oeuvres of these two artists suggests the diverging tendencies during this period in France; one artist favoring a strongly Academic approach to painting in both its execution and subject matter and one that romanticized his subjects, while Chaigneau rejected mythologizing scenes and became part of the second generation of the Barbizon artists. Chaigneau stayed only two years in Bordeaux before moving to Paris in 1847 where he lived with his uncle Raymond Eugene Goethals, a painter of marine and landscape scenes. More importantly, however, was his welcoming by the artist and family friend, Jacques-Raymond Brascassat, a celebrated animalier – a painter of animals. This same year, Chaigneau began taking courses at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Shortly after beginning his courses in Paris, Chaigneau’s first painting was accepted into the Salon of 1848 with Souvenirs des Environs de Bordeaux (Souvenirs of the Environs of Bordeaux). The following year, he was listed as a student in the ateliers of three masters, Francis-Édouard Picot, with whom, again, Bouguereau was also working, Léon Coignet, and Brascassat. Both Picot and Cogniet, friends of one another, devised strict methods for preparing their students, especially for the coveted Prix-de-Rome recounted by the later member of the Academy, Isidore Pils (quoted in Albert Boime’s The Academy & French Painting in the Nineteenth Century, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986, pg. 22):

[Picot] also obtained good results by establishing in his studio, as had already been done by his friend M. Cogniet, a system of preparatory competitions by way of preparing for the École des Beaux-Arts. Once a month, the students’’ painted figures and sketches were assembled, and the five best of each were chosen in preparation for a final judgement held every three months. A silver medal, which Picot had specially struck for the purpose, was presented for the best of the fifteen figures and the best compositional sketch. The prize-winning works were exhibited in the studio, forming a little museum which was of interest to both old and new pupils and encouraged a spirit of emulation. The jury consisted of the master himself and five pupils who were not themselves competing for the prize.

Chaigneau may indeed have taken part in such rigid student competitions since he did try for the coveted Prix de Rome in 1853. While he was not awarded the prize, he did receive third place for his entry, an honorable placement in a very strict and limited competition awarding only a handful of artists in a period of years.

While it was undoubtedly important that Chaigneau experience the atelier of masters of divergent backgrounds and styles, it is clear that Brascassat was the one to most fully influence his style. Both Picot and Cogniet tended towards Neo- or Academic Classicism and often depicted historical or mythological scenes that were so foreign to the majority of landscape painters who instead depicted the beauty of their every-day and their environment. After all, it was Brascassat who, near his atelier on the rue de Clignacourt in Paris, kept a wolf and two fox at a stable nearby. Brascassat’s appreciation of nature was reflected in his student, Chaigneau, but Chaigneau distinguished himself from the others by his sensitive style (Mauclair, pg. 44):

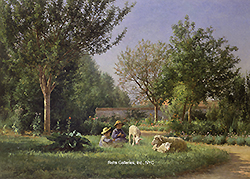

To speak more precisely about Chaigneau, to situate his animalier style a desirable distance from Brascassat, Jacque, Rosa Bonheur, Verwee, it is necessary to speak of the tender, gray, intimate quality of his light, the way in which he bathes the contours, by the particular softness of his models. One must think of Anton Mauve and Henri Duhen, because Chaigneau comes from one and announces the other…Chaigneau is a tender man who understands the poetry of the passage of tones. One can consider him, in his group, as an intermediary between the vigorous and broad method of Millet and the iridescent and fluid method of Daubigny.

His work began earning much praise and it was considered that it was Chaigneau’s “charm” which was his “supreme originality.” (reprinted in Marie-Thérèse Gazeau-Caille’s Hommage a Ferdinand Chaigneau: 1830-1906, ex. cat., Mairie de Barbizon, 1985, pg. 116) On October 3rd, 1854, he was given an honorable mention for the competition of historical landscape painting with Lycidas et Meris (Lycidas and Meris), an example of one of his early paintings that was influenced by his academic training in the mythological subject matter. That same year, the city of Bordeaux recognized his talents and awarded him a scholarship of 1500 francs to continue his studies in Paris, where the following year he took part in the 1855 Exposition Universelle, exhibiting Marais dans les Landes (Marsh in the Landes Region).

Paris could offer only so much to an artist of such particular persuasions as Chaigneau possessed. As his interest grew for painting landscapes and animalier scenes, it became more appropriate for him to leave the city and take refuge in the artistic center at Barbizon, the village to which he relocated in 1858. Anatole de la Forge wrote that (reprinted in Gazeau-Caille, pg. 117):

This faithful shepherd is the painter Ferdinand Chaigneau, the man of the sheep. Very researched, very like, much appreciated by artists and connoisseurs, this master lives detached, uniquely absorbed in his daily work. One never sees him in the rooms of the minister of the beaux-arts amongst the beggars seeking official posts. Ferdinand Chaigneau is a solitary man in the vein of Francois Millet and Theodore Rousseau, his masters and friends, the illustrious leaders of this great Barbizon school of which he remains one of its most brilliant continuators.

It was at Barbizon that countless other artists arrived to establish an artistic community where nature reigned supreme. While remaining in Barbizon, he nevertheless kept his ties with the Parisian art world and continued to submit his works to the annual Salon, submitting, for example works inspired by his time at Barbizon, such as his 1861 Salon entry, Rue de Village (Village Road).

A tendency common to many artists during this period, Chaigneau also allotted time to the graphic arts. In 1862, he became a member of the Société des Aquafortistes which was instituted this same year by Alfred Cadart and Auguste Delatre. Chaigneau not only had a painting studio in Barbizon, but also an engraving studio as well. Mauclair commented that Chaigneau’s “watercolors are of a remarkable technique, with a striking comprehension of black and white.” (pg. 45) Such media allowed artists to disseminate their work to a large audience unable to purchase a painting for themselves. It reflected the democratic ideals common to the sentiments of the Barbizon group.

Chaigneau’s painting was becoming highly sought after and many of his pieces were purchased by the state. In 1865, the State purchased Chaigneau’s L’Hiver, Carrefour de l’Épine (Winter, Épine Carrefour), and in 1870, purchased a second piece, Troupeau de Moutons en Plaine (Flock of Sheep in the Plains). Chaigneau’s later involvement in state affairs did not prove as positive after the beginning of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870. A year earlier, Chaigneau constructed a house with a small garden in Barbizon, called the “Bergerie” which was eventually converted into a small hospital for wounded victims of the war. But in January of 1871, he was arrested and put in prison in Fontainebleau. It was only after the armistice in 1871 that he was released. This same year he relocated back to Paris living in the faubourg Poissonnière during the winter.

It was not only the French State that was interested in many of Chaigneau’s best work. The American dealer Samuel Putnam Avery also sold several of his works to eager American patrons, while Chaigneau also began exhibiting at exhibitions outside of France, including his 1872 entry at the International Exposition in London, at the 1875 International Exposition in Santiago, Chile – for which he receive a first-place award, and the 1880 Universal Exposition in Barcelona.

Throughout the next decade, Chaigneau became a co-founder, along with fellow animalier, Charles Jacque, of the Société des Artistes Animalier, which was instituted in 1882 and which held their first exhibition on April 15th of this same year. A continually active artist, Chaigneau also began teaching and became part of the Société d’Instruction de Barbizon, which was then affiliated with the Ligue Française de l’Enseignement, of which he was the president. He also gave his son the proper tools to become an artist in his own right and saw the young boy premier at the annual Salon in 1896, when he was seventeen years of age. Chaigneau himself continued to submit actively to the Parisian salons, as well as other spanning the continents. As he grew older, a paralysis began to take over his body, preventing him from continuing his work as he had diligently done before. He died at Barbizon on October 22nd 1906.

Chaigneau, whose “supreme originality” earned him a “place between Rosa Bonheur and Jacque,” (reprinted in Gazeau-Caille, Journal des Arts, February 29th, 1884, pg. 116), represented “an entire school, and entire past, an entire world of yesterday…the last Barbizon follower, of a legendary Barbizon, of a Barbizon of the happy bohemian and of the proud poverty.” (reprinted in Gazeau-Caille, pg. 117) His death signaled the end of an era, but through his continued popularity with both audiences and museums alike, the contributions Chaigneau made to the traditions of the Barbizon group were etched in the history of nineteenth-century French painting. And, as Mauclair memorably wrote, “There will always be painters, but there will never be any more characters of such singular arrival as that of Ferdinand Chaigneau.” (pg. 46).

The biographical details in this biography have been taken from the previously cited exhibition catalog by Marie-Thérèse Gazeau-Caille: Hommage a Ferdinand Chaigneau: 1830-1906, ex. cat., Mairie de Barbizon, 1985.

Works by Jean-Ferdinand Chaigneau are presently found in the Musées des Beaux-Arts of Bordeaux (Jésus et la Samaritaine, Lysidas et Meris) and in Lyon (Troupeau de Moutons au Soleil Couchant), in addition to the National Gallery of Art (Le Petit Troupeau – etching, Moutons en Plaine– etching), among others.