Little is known of George Lance’s childhood in the medieval town of Little Easton in Essex beyond his birth date of 24 March 1802. In the early nineteenth century, Little Easton had one pub, The Stag, and one church, St. Mary the Virgin—and its claim to fame was largely based on the fact that it was recorded in the Doomsday Book manuscript written in 1086. Not surprisingly, Lance set out for London in search of training that would offer him a wider range of opportunities for the future.

In 1816, at age 14, he apprenticed to the history painter, Benjamin Robert Haydon, a talented if temperamental figure. Haydon’s career began with a successful debut at the Royal Academy in 1807, followed by commissions from influential aristocratic collectors such as Sir George Beaumont. For the young Lance, this somewhat heady environment offered the prospect of introductions to potential clients for his own work, as well as to London’s rapidly changing art world. Haydon’s approach to art education was based on the standard academic practice at the Royal Academy, which focused on the study of classical sculpture; this was then augmented by the direct observation of the Elgin Marbles, which were on display at the British Museum after 1816. Under Haydon’s tutelage, Lance was also schooled in history painting, and strongly encouraged to pursue this genre as the most rewarding career path.

Lance remained in Haydon’s studio for seven years, leaving in 1823 when his mentor was imprisoned for debt. During the last years of his art education, Lance also attended classes at the Royal Academy School, probably at Haydon’s suggestion, and in 1824, he began exhibiting at the annual Academy shows. Simultaneously, he made a decision to concentrate on still-life painting as his primary mode of expression. Although he still occasionally painted historical subjects, even winning awards for works such as Melancthon’s First Misgiving at the Church of Rome, 1836, it was still-life painting that captured his enduring attention.

Like many artists before him, Lance appreciated the still life masterpieces of seventeenth century Dutch and Flemish painters, especially that of Jan van Huysum whose works were avidly collected by English aristocrats and wealthy businessmen. Unlike his French counterparts, Lance would not have had the opportunity to view these paintings in a public museum until after the creation of the National Gallery of Art in 1824. It is far more likely that he first saw still life painting at the British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts under the Patronage of His Majesty, a private club founded in 1805 under the directorship of Sir George Beaumont, whom Lance no doubt met while studying with Haydon. The British Institution, as it is commonly called, sponsored an annual temporary exhibition of Old Master paintings, largely culled from the collections of its wealthy members.

Lance’s fascination with the natural world, perhaps emerging from his childhood in rural Essex, fueled his further examinations of botany, anatomy and horticulture. He took at least three courses of anatomical dissection between 1825 and 1847, always seeking to understand the underlying scientific structure of nature. This almost obsessive emphasis on natural history was part of the larger cultural context of nineteenth-century England, where the Royal Society led the effort to promote understanding of science in all of its diverse forms; scientific inquiry was directly linked to technological innovation and the belief that progress brought economic success that, ultimately, created positive social change.

In addition to his unquestionable absorption in natural science, Lance’s focus on still life painting was also a pragmatic decision. He came from a modest background without financial support, and had already witnessed the humiliating reality of debtors prison when Haydon had been unceremoniously incarcerated in 1823. Economic security depended on his ability to offer art that appealed to a steady market—and still life painting had proven itself to be a reliable product since its first appearance in seventeenth-century Holland and Flanders.

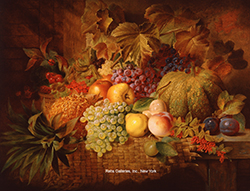

Lance was both fortunate and smart in maintaining a network of patrons who not only supported his work, but also recommended him to other collectors. Among the earliest of his patrons was Robert Vernon, a middle-class tradesman who made his fortune contracting horses to the British army during the Napoleonic wars. By 1826, when he purchased his first still life painting from Lance, Vernon was a wealthy art lover on his way to establishing the collection of contemporary British art that would eventually become the foundation for what is now Tate Britain. An 1834 still life, entitled The Autumn Gift, is typical of the paintings that Vernon purchased from Lance. It is filled with the abundant harvest of the season—glistening grapes, rosy apples and pears as well as raspberries still on the branch—all displayed in a willow basket on a rustic woven mat atop a country table. What is somewhat unusual here is the lack of any other context for the scene, requiring the viewer to concentrate fully on the beauty of the fruit in its meticulously detailed naturalism.

Vernon continued to acquire Lance’s still life paintings throughout his increasingly prosperous career. One of the most revealing is The Red Cap, 1847, which appears to be a gentle lampoon of human foibles, but may also be a more biting comment on the political realities of mid-century Europe. The composition here is framed by a dim background arch, against which a monkey pauses uncertainly as he tries to choose between food and play. These types of “monkeyana” pictures were very popular in the early 1800s, much like the images of dogs playing cards in the twentieth century. However, Lance has depicted the monkey wearing the red cap of liberty, and in 1847, this was a direct reference to the revolutions then engulfing Europe. As a successful entrepreneur, and the leader of a still-life revival movement in Britain, Lance’s political sympathies were unlikely to have supported the socialist fervor of German, Polish and French activists.

Over four decades, Lance’s reputation spread to the United States as well as Australia and Canada. His work was regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy and at the British Institution as well as at private commercial outlets such as the Suffolk Street Gallery. An infrequent, but charming subset of Lance’s work was his painting of prize fruits and horticultural produce for the aristocratic estates of Woburn Abbey and Blenheim Palace. His willingness to undertake these types of commissions, even when he had become a very prosperous artist, underscores again both his fascination with botanical sciences and his pragmatic approach to earning his living as a painter.

Lance’s embrace of still life painting as a legitimate genre in the 1820s makes him a pioneer in the still life revival movements of the 1830s and 1840s throughout Europe. Although there is no record of him traveling to either Amsterdam or Paris, it seems most likely that he would have done so once his career was well established. It is tempting to speculate about his influence on the later still-life revivals there.

George Lance died on 8 June 1864 at Sunnyside, Merseyside near Liverpool. He was 62 years old. Almost ten years later, Christie’s auctioned the contents of his studio on 27 May 1873; there were nearly 400 works offered at auction.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

City of Manchester Art Galleries, Manchester, UK

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

Tate Britain, London

Victoria and Albert Museum, London