BIOGRAPHY - Emilio Sánchez Perrier (1855 - 1907)

Born in Seville, Spain on October 15, 1855, Emilio Sánchez-Perrier was raised in a modest middle class family. His father was a clockmaker, who undoubtedly expected his son to follow him into the family business. The boy demonstrated a talent for drawing and painting, however, and by 1868, he was attending the school known today as the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de Santa Isabel de Hungría. [i] There he studied with two genre painters, Joaquín Domínguez Bécquer (1817-1879) and Eduardo Cano de la Peña (1823-1897). Both of these artists were associated with a genre style known as costumbrismo that was prevalent in nineteenth century Spain. It offered viewers a satirical—but not overtly political—interpretation of daily life and customs. Sometimes, the scenes were based on literary models, but most often the painters focused on folklore and regional mores. Perhaps most important to a young artist beginning his education, the technical training for this type of painting was grounded in the realistic depiction of the world.

Within a few years, Sánchez-Perrier was pursuing his art education at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes in Madrid, where he studied with Carlos de Haes (1829-1898). This was a fortuitous development for the young painter. Haes was a Spanish-Belgian artist, born into a banking family in Brussels, but spending much of his childhood in Málaga where he studied with the neoclassical portrait painter, Luis de la Cruz y Rios (1776-1853). In 1850, he returned to Brussels to study with the Flemish painter Joseph Quinaux (1822-1895) who introduced him to the emerging Realist movement in Belgium and the increasingly international art community in Brussels. During his time in Quinaux’s studio, Haes worked alongside classmates such as Hippolyte Boulenger (1837-1874), the artist who would transform the definition of Belgian landscape painting in the 1860s. Quinaux also encouraged his students to travel, and Haes apparently took his advice, visiting Holland, France and Germany during these years. When he returned to Madrid to take up a teaching position at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in 1857, he offered students a well informed international perspective on the state of contemporary art.

For Sánchez-Perrier, Haes not only introduced him to contemporary plein air landscape painting, but he also provided the young Sevillan with a window onto other European art centers. Haes took his students on extended painting expeditions throughout Spain, taking advantage of the newly developed railway system to reach even the most distant regions of the nation. On site, they would paint directly from nature, training their eyes to observe carefully regardless of the environment or weather conditions. In later years, art critics often noted the meticulous craftsmanship of Sánchez-Perrier’s images, frequently suggesting that he must have used photographs as his sources for these paintings. While it would not be surprising to learn that he used photographs, it is equally likely that his training with Haes, and the Flemish tradition upon which it was based, was the original source for his careful attention to detail.

During the early 1870s, Sánchez-Perrier met two other artists who would become important influences in his career. First was Martin Rico y Ortega (1833-1908), who had returned to Spain from his home in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). Although the two men were separated by more than twenty years in age, they began a long-term friendship after meeting in Seville when Sánchez-Perrier returned to his home town to see family. In 1871, the two of them set out on an extended visit to Granada, where they lived and painted for several months. It was during these months in Granada that Sánchez-Perrier also met Marià Fortuny i Marsal (1838-1874), the esteemed Catalàn painter whose career was cut short by malaria just a few years later at age thirty-six. From both of these artists, Sánchez-Perrier gained an understanding of the value of broadening his horizons beyond Spain; Fortuny had traveled extensively in north Africa and lived in both Paris and Rome, while Rico had led a peripatetic life, journeying throughout Europe before settling in Paris in the 1860s. [ii] The 1870s painting Evening in Seville, currently in the Akron Art Museum collection, displays these early influences clearly in the scrupulous attention to detail, the use of intense color and the luminous presentation of the Andalusian landscape.

Sánchez-Perrier began his career in earnest in 1877 when he submitted his work to the regional art exhibitions in Seville and Cadiz. A year later, he made his debut at the national exhibition in Madrid with six paintings. [iii] In 1879, he won his first official recognition with a gold medal at the Cadiz regional exhibition. Several months later, he decided to expand his options by moving to Paris where he began working in the studio of the Barbizon painter Auguste Boulard (1825-1897). Sánchez-Perrier also studied with Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) and Félix Ziem (1821-1911), two very different painters representing the French academic tradition and the naturalist/impressionist approach respectively.

The Spanish community of artists in Paris offered a warm welcome to the twenty-two-year old Sánchez-Perrier. Although less famous than the twentieth century Spanish artistic enclave in Paris, there was already a thriving community in the mid-nineteenth century. Both Rico and Fortuny had lived in Paris in the 1860s; Sánchez-Perrier likewise found a home among the artists there, and in particular, a lifelong friend in Luis Jiménez y Aranda (1845-1928), a fellow Sevillan who had arrived in Paris in 1878. [iv] The two men shared a studio in Montparnasse at rue Boissonade, 11 at least until 1888. [v]

Sánchez-Perrier lost no time in making his Salon debut in Paris, exhibiting three paintings—The Alcazar Vegetable Garden in Seville, Winter and Andalusia—in May 1880. His work was noticed immediately, with one commentator remarking that The Alcazar Vegetable Garden in Seville was “...direct and detailed like a small photograph, and not without talent.” [vi] From the outset, Sánchez-Perrier’s work was well received and widely noted among newspapers and journals covering the Paris art world.

To cite just a few examples Sánchez-Perrier’s reception by French art critics, Le Gaulois littéraire et politique remarked on June 21, 1881 that “Monsieur Sánchez-Perrier has concentrated all the rays of the Spanish sun in his small [painting] The Alcazar Vegetable Garden in Seville, where the orange trees bear gleaming fruit...” [vii] In 1883, his work received a comment in the Mémoires de la Société d'agriculture, sciences et arts d'Angers where it was described as being in the tradition of Brueghel, where one could “...count the leaves on the blackberry bushes and almost grasp the stones beneath them.” [viii] In 1884, his painting of the Guadaira River attracted attention from several sources including Le Monde illustré, 3 mai 1884; La Jeune France, Juin 1884; L'Europe artiste, 25 mai 1884. The reviewer from La Jeune France remarked that “the care and precision with which it was painted and the natural impression that it makes are guaranteed. [It’s] very good, very good, this little painting.” [ix]

With his reputation well established by the mid-1880s, Sánchez-Perrier followed in the footsteps of Rico and Fortuny and began to travel beyond France and Spain. Dated paintings document his stays in Venice in 1885 and in Morocco in 1887, but it is likely that he traveled widely throughout his career. Venice was a particularly appealing subject for him as were the river valleys of northern France. Although Paris remained his home base, it is evident from the paintings that Sánchez-Perrier returned often to the regions around Seville and Granada as well.

He continued to exhibit his work annually at the Paris Salon and in 1886, received his first honorable mention. Again, his work was widely covered in articles about the 1886 Salon. In 1886 Sánchez-Perrier also exhibited his painting, Calvaire d’Alcala, in Normandy where it was noted favorably in La Revue normande : littéraire & artistique : organe mensuel de l'Académie normande. [x] The artist’s decision to exhibit his work in Normandy, albeit a depiction of a Spanish landscape, raises questions about his association with this region of northern France. Was he working there often? Did he have friends living in the area? Was he following in the footsteps of the Impressionist painters who frequented the seaside resorts and small villages in the area? Sánchez-Perrier’s fascination with light—and his skill at capturing the subtle colors of light whether in Picardie or Venice—suggests the influence of Impressionism, but his brushwork remains firmly grounded in the tradition of his Madrid professor, Carlos de Haes.

In 1889, Sánchez-Perrier was honored with a silver medal for the painting Guadaira at the Exposition universelle in Paris. Although little is known about his personal life, the catalogue for the international exposition lists him as living at a new address, the boulevard de Port-Royal, 31. Presumably, the move was necessitated by Luis Jiménez y Aranda’s decision to move out of the city to Poissy, thus requiring Sánchez-Perrier to find a new place as well, although in fact, he moved just a few blocks away.

Throughout the 1890s, his career continued to flourish. He is elected as an Associate of the Sociéte nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1891 and, in 1894, as a member of the Société Générale des Beaux Arts. The critical reception of his work remains consistently positive; a reviewer for L'Intransigeant in 1897 declared the then forty-two-year-old Sánchez-Perrier to be “an artist of the future”. [xi] This decade was also a period of expansion in the art market for Sánchez-Perrier’s work. His paintings were increasingly popular in the United States where private art collectors eagerly acquired his landscapes of the European countryside.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Sánchez-Perrier turned his attention more and more often to Spain. Although he had exhibited his paintings in Madrid’s national exhibitions in earlier years, and made regular trips to Andalusia throughout his career, it was not until 1903 that he became a member of Seville’s Academy of Fine Arts. It may be that he returned to his hometown to live at this time. The Museo del Prado appears to have purchased his award-winning painting, Febrero (February), in 1890; and his paintings are listed as being in Barcelona’s Museu Municipal de Belles Arts (today the Museu Nacional d’art de Catalunya) in a 1906 French tourist guide to Spain and Portugal. [xii] Nonetheless, Sánchez-Perrier’s final years remain somewhat obscure. He died in Granada on September 13, 1907 just a month before his fifty-second birthday.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Akron Art Museum, Akron, Ohio

Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, New York

Musée Camille Pissarro, Pontoise, France

Museo de Belles Artes, Seville, Spain

Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga, Spain

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

[i] The first Academy of Art in Seville was founded in 1660 by the baroque painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617-1682) and the architect Francisco Herrera the Younger (1627-1685). This eventually became the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de Primera Clase de Sevilla, which was the name of the school when Sánchez-Perrier attended. That name was subsequently changed in 1896 when it established an affiliation with the university.

[ii] Shortly after his initial meeting with Sánchez-Perrier in the early 1870s, Rico would move to Venice, where he was based until his death in 1908.

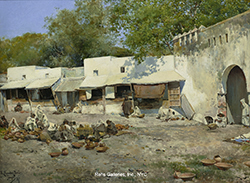

[iii] The paintings Sánchez-Perrier submitted to the national exhibition in Madrid in 1878 included:The Praetor’s Railing in the Garden of the Casa de Pilatos; Kitchen Garden with Hens in Alcalá de Guadaíra; Sunset; Banks of the Guadaíra River; Lagoon with Duck; and The Mill at Mesía.

[iv] For more information about the Spanish arts community in Paris, see Laura Karp Lugo, “Catalan Artists in Paris at the Turn of the Century” in Susan Waller and Karen L. Carter, Foreign Artists and Communities in Modern Paris, 1870-1914: Strangers in Paradise (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. 2015) 111-124.

[v] Explication des ouvrages de peinture et dessins, sculpture, architecture et gravure des artistes vivans, No. 2234, No. 2235 (Paris: Salon des artistes français, 1888) 340.

[vi] “Petite étude directe et fouillée comme une photographie minutieuse, et qui n’est pas sans talent.” Théodore Véron, Dictionnaire Véron, ou mémorial de l'art et des artistes de mon temps (Paris, Institut universel des sciences, des lettres et des arts du XIXe siècle, 1880) 430. Translation by the author.

[vii] Le Gaulois littéraire et politique, 21 juin 1881(2). “Enfin, M. Sanchez-Perrier concentre tous les rayons du soleil d’Espagne en son petit Potager de l’Alcazar à Séville, où les orangers portent des fruits étincelants, où toutes les plantes absorbent du feu.” Translation by the author.

[viii] Académie des sciences, belles-lettres et arts, Mémoires de la Société d'agriculture, sciences et arts d'Angers (Angers, 1883) 298.

“Pour consoler ceux qui aiment une facture habile et l’exécution des détails poussée avec un fini digne de Breughel, je les conduirai devant le petit paysage de M. Sanchez-Perrier. Là, ils pourront compter les feuilles de ronces du premier plan et presque saisir les cailloux qui sont à leurs pieds.” Translation by the author.

[ix] “Le Salon de 1884”, La Jeune France, Juin 1884 (27-28).

“Ainsi, j’ai la plus grande confiance en un paysage tel que celui de M. Sanchez-Perrier, les Bords du Gudaira. Le soin et la précision avec lesquels il a été peint, l’impression bien nature qu’il fait sont des garanties. Très bien, très bien, ce petit tableau.” Translation by the author.

[x] Albert Hüe, La Revue normande : littéraire & artistique : organe mensuel de l'Académie normande (Académie normande, 1886) 10.

[xi] “Le Salon du Champs de Mars”, L'Intransigeant (Paris) 24 avril 1897 (2).

“”M. Sanchez-Perrier nous vient du pays des castagnettes et du boléro. Le petit paysage très brillant et très achevé, qu’il nous en a rapporté est d’un véritable coloriste et décèle [reveals] un artiste d’avenir.”

[xii] Adolphe Joanne, Espagne et Portugal, par Paul Joanne (Paris: Hachette, 1906) 69.

| |||||||||