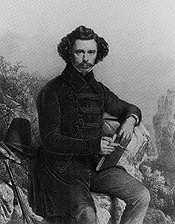

BIOGRAPHY - Barend Cornelis Koekkoek (1803 - 1862)

One of the most celebrated Dutch landscape artists of the nineteenth century was Barend Cornelis Koekkoek. His works were typical of the period’s landscape painting, which combined “a romantic feeling for nature with a classically inspired manner, so that even when nature assumes dramatic form in the guise of a gathering storm, the brush is unmoved.

(Marjan van Heteren, Guido Jansen, and Ronald de Leeuw, The Poetry of Reality: Dutch Painters of the Nineteenth Century, Amsterdam: Waanders Publishers: Rijksmuseum, 2000, pg. 8)

Koekkoek became a much sought after artist through his mountainous, forest and idyllic woodland scenes, as well as his majestic oak trees, gathering thunderstorms, and masterful use of light.

Barend Cornelis Koekkoek was born in 1803 in Middleburg, the Netherlands into a family of artists. He received his first art instruction from his father, Johannes Hermanus Koekkoek (1778-1851), a well-known marine artist, and studied with Abraham Kraijestein (1793-1855) at the Middleburg Drawing Academy. In 1823, the young Koekkoek enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam after being granted a scholarship of 300 guilders for three years by King Willem I. He studied there with Jan Willem Pieneman (1779-1853), mostly known for his contemporary history scenes of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and for being a teacher to an impressive group of artists, as well as with Jean Augustin Daiwaille (1786-1850), the portrait painter and lithographer.

After completing his studies at the Academy in 1826, Koekkoek moved to Hilversum, then to Beek before returning to Amsterdam in 1829. During that time he traveled regularly in the surrounding countryside. His first success came in 1829, when he won the gold medal of the Felix Meritis Society in Amsterdam for his painting Landscape with a Rainstorm Threatening (1829; Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum). This early work was described as “notable for its accurate and sober study of nature; it marked Koekkoek’s commitment to a style of landscape divorced from both the predominantly topographical approach of the 18th century and from the flat and decorative manner of contemporary mural painting.” (Annemieke Hoogenboom “Koekkoek, Barend Cornelis,” Grove Art Online Dictionary) Moreover, in The Poetry of Reality: Dutch Painters of the Nineteenth Century, Guido Jansen wrote that while Koekkoek’s painting “shows little of the consummate skill in rendering woodland scenes which mark his later pieces and which won him recognition throughout Europe,” yet “in its presentation of nature this work anticipates the idyllic woodland and mountainous scenes with which the artist won such renown in later years and for which he was to become the most applauded Dutch landscape artist of his day.” (pg. 67)

In 1833, Koekkoek married Elise Thérèse, the daughter of Jean Augustin Daiwaille, his former instructor at the Art Academy in Amsterdam. A year later they moved to Germany and settled in the town of Cleves, located in the hilly woodlands close to the Rhine basin. From there, he made annual summer expeditions to other parts of Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg, and brought back many sketches, which he used primarily as studies. However, unlike his fellow artists, Koekkoek did not reproduce these studies rather he used them as an indirect source of inspiration. During the 1830s, he continued to study nature in order to perfect his style, and painted a number of scenes of the Rhine, of winter scenes and of “the first densely wooded landscapes that were to establish his fame.” (van Heteren, Jansen, and de Leeuw, pg. 74) While he based his style on that of seventeenth-century Dutch artists like Meindert Hobbema (1638-1700), Jan van Goyen (1596-1656), and Jan Wijnants (c.1635-1684), some of his early paintings also recall the works of his contemporary Andreas Schelfhout (1787-1870) such as in Winter Landscape with Peasant’s House and Frozen Canal (1837; Haarlem, Teylers Museum).

After 1840, Koekkoek began producing landscapes that underlined his romantic attitude towards nature for which he became so famous. These works featured ruins, chapels and other idyllic elements, as well as his signature large oak trees, dramatic skies and gathering thunderstorms. As noted by Hoogenboom, he “tended to set small figures in vast landscapes with deep valleys, inhospitable crags and proud castles; these scenes are made more dramatic by the strong contrasts between light and dark, as in View in the Rhine Valley (1843; Dordrecht, Dordrechts Museum) and Landscapes near Cleves with a Fire (1846; Antwerp, Kon. Mus. S. Kst.).” (Grove Art Online Dictionary) As for Koekkoek’s impressive woodland scenes and masterful depiction of the light effects of dawns and sunsets, View in the Woods (1848; Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum) may serve as an example:

It represents a level that few of his contemporaries were capable of attaining. The effect of the setting sun’s warm light on the trees, for instance, is done with great expertise. The idyllic mood of a warm summer’s day is heightened by the languidly ruminating cattle in the right foreground. On the left, near a little waterfall, a woman is conversing with a man on horseback, observed by a few shepherdesses at the foot of the huge oak. Even the heavily laden donkeys seem unaware of their burdens. (van Heteren, Jansen, and de Leeuw, pg. 88)

Despite the romantic mood evoked by Koekkoek’s images, he executed his work with great care and his “painting method always remained painstakingly sound, with no displays of bravura.” (Hoogenboom, Grove Art Online Dictionary) This method was typical of the period’s Dutch romantic painting, which rarely manifested the intense drama associated with similar works from France, England and Germany. It was only in the 1880s that Dutch artists began to express a “mood of suffering or impassioned attitude” in their works. (Harry J. Kraaij, Charles Leickert 1816-1907: Painter of the Dutch Landscape, Schiedam, The Netherlands: Scriptum Signature, c. 1996, pg. 10)

Koekkoek reached the peak of his fame in the early 1840s. He gained international recognition in 1839, when he sent a large Woodland scene to exhibitions in The Hague and Paris. In 1841, he published a book entitled Thoughts and Recollections of a Landscape Artist (Herinneringen en mededeelingen van eenan landschapschilder), in which he gives an account of one of his art trips down the Rhine, and describes his thoughts about the ideal landscape art. That same year, he was proclaimed the Prince of Landscapists. (van Heteren, Jansen, and de Leeuw, pg. 87) From that time, Koekkoek received an increasing number of commissions from many distinguished patrons such as King Willem II of the Netherlands, Tsar Alexander II of Russia, and King Friederich Wilhelm IV of Prussia. With the high demand for his work, forgeries began to appear in the market, as a result, he stared issuing certificates of authenticity by 1847.

Koekkoek was a prominent figure in the art world during his life and after his death. In 1841, he founded a drawing academy in Cleves where many young artists went to study with him, and established in 1847 a local society to promote the appreciation of arts. His grand residence which he had built in 1848 for his family became the Städtisches Museum Haus Koekkoek in 1960 holding many of his paintings, studies and drawings. During his lifetime, he exhibited regularly in The Hague, Rotterdam, Amsterdam and Paris where he won medals in 1840 and 1845. Koekkoek also received numerous honors and was awarded the Netherlands Order of the Lion and the Belgian Order of Leopold.

Selected Museums

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Dordrechts Museum, Dordrecht

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Teylers Museum, Haarlem, (The Netherlands)

Städtisches Museum Haus Koekkoek, Cleves, (Germany).