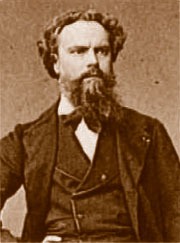

BIOGRAPHY - Alexandre Cabanel (1823 - 1889)

Alexandre Cabanel was one of mid-nineteenth France’s most well respected academic artists. During his lifetime, his reputation encompassed all types of painting, from portraits to religious scenes, and large interior décorations. Not surprisingly, this distinguished career began with a precociously early display of artistic talent. His early schooling in his hometown of Montpelier revealed a talent for drawing, and in 1834 at age ten, he was permitted to attend the local art school. Five years later, the municipal authorities gave him a grant to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris where he enrolled in the studio of François-Edouard Picot (1786-1868) in October 1839. Picot had trained in the prestigious studio of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), and continued to teach the neoclassical values associated with his mentor, albeit with more romantic subject matter

The following years were full of study and excitement as the gifted youth from Montpelier evolved into a well-educated and sophisticated painter. During these years, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts’ curriculum focused intensely on the study of literature, history and religion as well as the visual arts; this included the traditions of ancient Greece and Rome as well as medieval church writings and the classical French canon of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in both literature and painting. [i] The young Cabanel seems to have absorbed the scope of this education eagerly, and like his classmates, found it to be a rich resource for creating compelling visual imagery.

Cabanel made his Salon debut in 1843 with the painting Agony in the Garden for which he received a second place in the Prix de Rome competition. In 1845, he again won second place in the competition, this time losing to Léon Bénouville (1821-59) who was also a student in Picot’s atelier. A comparison of the two finalists’ paintings of Christ at the Praetorium (both still in the collection of the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris) reflects the division between neoclassical and romantic approaches to painting, even within the École itself. Bénouville’s work depicts the figure of Christ at the center of a renaissance-inspired pyramidal composition surrounded by mocking tormenters, while Cabanel places the figure of Christ slightly off-center and dramatically spotlighted against the surging group of persecutors. Fortunately, there were two scholarships available in 1845, so both Cabanel and Bénouville were able to pursue their studies at the Villa Medici in Rome.

Like many students before him, Cabanel avidly absorbed as much art and culture as possible during his years in Rome. The opportunity to study both Roman antiquities and renaissance masterpieces provided the artist with direct exposure to painting and sculptural techniques that he could only imagine back in Paris. During these years, Cabanel also made the acquaintance of Alfred Bruyas (1821-76), another young man from Montpelier, who was eager to study the history of art in Rome. Unlike Cabanel, however, Bruyas was primarily interested in creating an art collection, and he had inherited the wealth to accomplish that goal. Beginning in 1846 when Cabanel painted a Portrait of Alfred Bruyas, the two men established a long-standing friendship. Other paintings for Bruyas from the years in Rome included Albaydé, La Chiaruccia, and Man Contemplating, A Young Roman Monk, all created in 1848, and today part of the exemplary nineteenth-century art collection at the Musée Fabre established by Bruyas in Montpelier. Also in the Musée Fabre collection are two other paintings that Cabanel created during his years at the Villa Medici: St. John the Baptist, 1849, and The Death of Moses, 1850. These works again illustrate the characteristic tension in Cabanel’s approach to painting; the image of St. John the Baptist clearly shows the influence of Raphael’s classically composed Vatican frescoes, while The Death of Moses is a more theatrical depiction based on the Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes as well as his sculpture of Moses, originally commissioned for the tomb of Pope Julius II in 1505.

Interestingly, it was The Death of Moses that Cabanel chose to exhibit at the Salon of 1852 after his return to Paris. It won a second prize medal, but more importantly, it helped to establish the artist as a promising young painter. In addition to the public recognition of his talent at the Salon, Cabanel continued to have a supportive patron in Alfred Bruyas, who commissioned a number of paintings during these years. Most of them, including a Self-Portrait (1852) painted at Bruyas’ request, reflect Cabanel’s growing romanticism. In this image, he depicts himself as slightly brooding figure in somber shades of black and brown with stark highlights on his collar and forehead--very much in the style of Eugène Delacroix’s Self-Portrait from 1837.

The most challenging new project, however, was a municipal commission from architect Jean-Baptiste Cicéron Lesueur (1794–1883) for the decoration of a set of twelve pendentives at the Paris city hall, the Hôtel de Ville. Located in the Salon des Caryatides, each pendentive depicted a traditional seasonal image based on the months of the year; for example, April is titled The Awakening of Nature while October illustratedThe Fall of the Leaves. This type of seasonal cycle dates at least as far back as the medieval period in France when monthly images provided the basis for devotional meditations. By the eighteenth century, Louis XIV had transformed this traditionally Christian subject matter into a glorification of his monarchy in a series of Gobelin tapestries titled The Royal Residence Series. For Cabanel, the Hôtel de Ville décoration in 1852-53 represented the beginning of a significant career as a large-scale muralist.

Two years later in 1855, Cabanel was part of the interior design team that handled the renovation of the eighteenth century Hôtel Chevalier de Montigny for the Péreire brothers, financiers and real estate brokers of considerable wealth; in particular Cabanel was assigned to paint the ceiling in the Grand Salon. In the central circular coving of this elaborately carved ceiling, he created an Allegory of the Five Senses surrounded by medallions depicting allegories of poetry, fanciful poetry, dance and eloquence. The effect is one of rococo exuberance combined with the emerging extravagance of Second Empire Paris. Five years later, the Péreires would commission Cabanel to design additional murals for this room, this time a series of six wall panels featuring the Hours of the Day. Today, the building is home to the British Embassy, and Cabanel’s murals remain on display.

Other commissions for similar décorations soon followed: five rooms at the Hôtel Say on the Place Vendôme in 1855, and the very large ceiling of the Pavillon de Flore at the Palais des Tuileries in 1869. Sadly, both both the Hôtel de Ville and the Pavillon de Flore murals were destroyed during the Commune of 1871, but Cabanel painted another version of The Triumph of Flora for the Cabinet des Dessins in the Louvre in 1872.

The 1850s were an especially productive period in Cabanel’s career. In addition to the highly visible and prestigious décorations, he developed a number of large religious compositions such as The Glorification of Saint Louis, 1853, (Musée Fabre, Montpelier), which was commissioned for the Gothic chapel, Sainte-Chapelle, at the royal Château de Vincennes; the subject of Saint Louis was historically linked to the chapel itself as the site where Louis IX’s relics of the Crown of Thorns were kept until the construction of the more famous Sainte-Chapelle in Paris was completed. For Cabanel, this project enabled him to establish an association with the reigning monarch of his own time, Napoleon III, which was crucial to his success. The painting was subsequently exhibited at the Salon of 1855, together with another religious painting, Christian Martyr, (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Carcassone); that same year, the artist received the Legion of Honor medal, thus clearly identifying him as one of the leading academic painters of his era.

During this decade, Cabanel exhibited regularly at the annual Salon in Paris, and continued to expand his artistic repertoire, including an increasingly prevalent exploration of historical genre scenes. This anecdotal approach to history painting had been pioneered much earlier in the nineteenth century, but it continued to have great appeal for the middle-class art collector. One of the key figures promoting this type of subject was Adolphe Goupil, an art dealer and publisher, who often commissioned paintings that he would then publish as colored prints available at affordable prices to a wide audience. Cabanel’s 1859 painting, Michelangelo in His Studio Visited by Pope Julius II, (Musée Goupil, Bordeaux) was commissioned by Goupil, and seems to have been the artist’s first venture into this type of print production.The subject matter is entirely imaginary, but it nonetheless captures the admiration of mid-nineteenth century audiences for the work of a renaissance master such as Michelangelo; it also showcases the social status of the artist as a person worthy of receiving a private visit from the pope.

By the 1860s, Cabanel had built a reputation as a leading representative of France’s artistic tradition. In 1863, he was elected a member of the Institut de France and appointed as a professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. At the annual salons, he won the Grande Médaille d'Honneur in 1865 and in 1867. Throughout this time period, he also received numerous portrait commissions from members of the French aristocracy, including one from Emperor Napoleon III in 1865 (Musée de l'Impératrice, Compiègne, France). In short, his career was not only secure, but growing.

From an art historical perspective, however, one of the most significant events of the mid-nineteenth century was the ground-breaking Salon des Refusés exhibition in 1863. This “salon of the rejected ones” was a direct result of the Salon jury’s decision to refuse an unprecedented 2783 works of art for inclusion in the annual exhibition. The frustrated “refusés” artists petitioned the government for reconsideration, and after a personal visit from Napoleon III, the government issued a notice stating that it wished “to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints.” The rejected artists were then granted an exhibition space adjacent to the official Salon where the public could indeed make its own assessment of the artistic merit of artists like Edouard Manet, James McNeil Whistler, Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, Johan Jongkind, Henri Fantin-Latour and many others. As members of the original Salon jury, Cabanel and his colleagues William Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme, had argued against the acceptance of artwork that they did not believe reflected the French academic tradition, thus deepening a rift between accepted artistic methodologies and avant-garde experiments.

It was also in 1863 that Cabanel’s most famous painting,The Birth of Venus, (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) was exhibited at the Salon--and subsequently purchased by Napoleon III for his private art collection. The theme of Venus was especially popular during this time, with examples by Paul Baudry, The Pearl and Wave (1862, Prado Museum, Madrid), and Eugène-Emmanuel-Amaury Pineu-Duval, The Birth of Venus, (1862, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille) also on display at the 1863 Salon. [ii] There are numerous historical precedents for this subject matter, ranging from Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) to Cabanel’s own 1861 mural of Water at the Hôtel Say on the Place Vendôme, but ultimately, the appeal of these images is their eroticism. The classical narrative is merely a pretext for portraying a seductively painted nude woman.

In spite of Cabanel’s conservative position in regard to avant-garde art, he was an influential and open-minded professor at the Ecole des-Beaux-Arts. His pupils numbered in the hundreds, and they were routinely represented at the Salons and among the Prix de Rome winners. One testament to his popularity among his colleagues and students is that Cabanel was elected to serve on seventeen Salon juries between 1868 and 1888. The long list of Cabanel’s students also reflects his willingness to encourage each individual to find his own unique aesthetic; there were the pioneering naturalists Jules Bastien-Lepage and Emile Friant; orientalist Henri Regnault, impressionist Paul-Albert Besnard, and symbolist Eugène Carrière. In addition, there were a number of English and American painters who sought out Cabanel’s studio at the Ecole. As the New York Times noted in the painter’s obituary: “His pupils come from all nations and all ranks of society, and his protection was given to them constantly and with widest sense of friendliness. ...to one and all, the master, in spite of a strong personal and most classical tendency, gave encouragement to personal aptitude.” [iii]

In the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, Cabanel found himself working with the new democratic leadership of the Third Republic in a war-ravaged nation without a solid economic foundation. In an unusual move, the government turned to French artists not only to provide uplifting images to encourage national pride, but also to maintain France’s position as the cultural center of Europe. The rationale was that cultural leadership could function as an economic strategy that was not dependent on the destroyed industrial infrastructure, and more importantly, that could be implemented immediately. The hope was that French art and luxury goods would not only continue to sell well abroad, but that it would provide a reason for tourists to return to Paris bringing their spending money with them. As a short-term economic plan, it was successful enough to help mitigate the hardship of post-war reconstruction.

One of the most public projects from this post-war period was the completion of the décorations at the Panthéon. The building has a complex history, having been designed as the Church of Saint Geneviève in the 1760s, then transformed into a temple to the heroes of the French Revolution, then reconsecrated as a church in 1851, and ultimately designated as a national monument and mausoleum for French luminaries in 1885, which is what it remains today. For most of Cabanel’s life, however, it was a consecrated church, and it was in this context that he was asked to be part of a team of painters who would complete the last of the interior mural deigns.

Cabanel’s assignment was to depict the life of Saint Louis, a topic he was already familiar with from his 1855 painting of The Glorification of Saint Louis. His concept for the mural was to approach the composition as if it were an altarpiece surmounted by a frieze, albeit on an massive architectural scale. It took four years to complete, from 1874-78, and tells the story of Saint Louis from his boyhood years through his decades as one of France’s most beloved Christian monarchs.

After such a monumental undertaking, Cabanel turned to the more manageable scale of easel painting in the 1880s. He continued to accept portrait commissions, but he also began exploring what might be described as a symbolist sensibility in many of his mythological subjects. The image of Phaedra, 1880 (Musée Fabre, Montpelier) exemplifies this trend. It is both a traditional classical narrative and apparently, a late nineteenth-century scene of theatrical decadence. The sensual detailing of the fabrics, the furniture, and the ghostly pale figure of Phaedra all echo the orientalism of earlier decades; yet, there is a mundane quality to this scene that suggests a kind of “play-acting” as if these women are merely posing to amuse themselves. Likewise, the 1887 painting of Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Victims Sentenced to Death (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), has a similar staged quality. Considering that both Phaedra and Cleopatra were the subject of many plays, it is not unreasonable to consider the possibility that Cabanel’s inspiration in the 1880s was the theatre rather than ancient Greek and Roman literature.

Cabanel worked consistently up until the day before his death. He suffered a severe asthma attack on January 22, 1889, and was reportedly able to “sign all his studio sketches and prepare his art treasures for their future destinations” on that day. [iv] He died on January 23, 1889 at age 65.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Art Institute of Chicago

Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

Cleveland Museum of Art

Dahesh Museum, New York

Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Indianapolis Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Musée de l'Impératrice, Compiègne, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Béziers, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Carcassonne, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Valenciennes, France

Musée Fabre, Montpelier, France

Musée Goupil, Bordeaux, France

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Musée du Louvre, Paris

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Snite Museum of Art, Notre Dame University, South Bend, Indiana

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

[i] Hilaire, Michel and Sylvain Amic. Alexandre Cabanel, 1823-1889, La tradition du beau. Exh. cat. Montpelier: Musée Fabre. Paris: Somogy éditions d’art, 2010.

[ii] In 2011, the Musée Fabre mounted a retrospective of Cabanel’s work which included all three of these paintings in the exhibition. For a review of this exhibition and images of the actual installation of the Venus paintings side by side, please see: Alison McQueen, Alexandre Cabanel: La Tradition du Beau at www.19thc-artworldwide.org/index.php/spring11.

[iii] “Cabanel’s death and his Popularity” The New York Times, January 26, 1889.

[iv] “Cabanel’s death and his Popularity” The New York Times, January 26, 1889.

| ||||