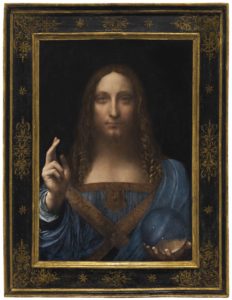

Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi

The final act of the decade-long Bouvier Affair has come to an end. The series of legal actions by Russian billionaire Dmitri Rybolovlev against the Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier ended in December 2023. However, there was still the matter of Rybolovlev’s lawsuit against Sotheby’s for allegedly aiding and abetting Bouvier in his supposed fraud. After a 21-day trial, a federal jury in New York took five hours to find Sotheby’s not liable for Rybolovlev’s damages.

The original feud between Rybolovlev and Bouvier started in 2017 when the Russian oligarch alleged that Bouvier had worked as his agent in amassing an impressive art collection. The Swiss dealer acquired thirty-eight artworks for around $2 billion on Rybolovlev’s behalf between 2002 and 2014. The most well-known piece was Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, which later sold at Christie’s for $400 million (or $450.3 million w/p), becoming the most valuable painting in the world. Rybolovlev accused Bouvier of defrauding him of over $1 billion, and, in some cases, Sotheby’s helped him do it. Sotheby’s, of course, has denied this, asserting that it obeyed “all legal requirements, financial obligations, and industry best practices during the transactions of these artworks”.

Salvator Mundi took a central role during the trial, as it is the most well-known of the four paintings Bouvier bought at Sotheby’s, which he later sold to Rybolovlev. Bouvier purchased the work in 2013 for $83 million, turning around and selling it to the Russian billionaire for $127.5 million. Rybolovlev claims that Bouvier legally could not charge such large markups since he acted as his agent. However, Bouvier asserted that he acted as a dealer independent of Rybolovlev and could sell paintings for whatever price he wished. Sotheby’s stated that Bouvier was the only buyer to their knowledge and that whatever he did with the paintings afterward was none of their business. Sotheby’s lawyers even argued that Rybolovlev was at fault here for failing to do his due diligence and protect himself against predatory practices. In his lawsuit, however, Rybolovlev alleges that Sotheby’s was aware of Bouvier’s scheme and did nothing to prevent it. Rybolovlev’s legal team presented some evidence that Sotheby’s may have known him to be the final buyer since Sotheby’s specialist Samuel Valette viewed Salvator Mundi with both Bouvier and Rybolovlev before the purchase at the Russian oligarch’s Manhattan apartment. When called to testify, Valette stated that he did not connect Rybolovlev’s presence there to Bouvier buying the painting on his behalf. Rybolovlev further argued that Sotheby’s purposefully inflated their estimate ranges and insurance valuations to hide Bouvier’s markups.

Sotheby’s did acknowledge that Rybolovlev seems to have been taken advantage of but that it was not the auction house’s burden. Furthermore, Rybolovlev and his legal team have found a silver lining to this outcome despite the loss. They say that whether they won or not, the trial allowed the public a short glimpse into the inner workings of the art world, which are often intentionally wrapped up in secrecy. Rybolovlev’s lawyer, Daniel Kornstein, stated that the art market’s “lack of transparency” made their case so difficult to make in the first place.

For previous updates on the Bouvier Affair:

The Bouvier Affair: Sotheby’s Cleared In Lawsuit

Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi

The final act of the decade-long Bouvier Affair has come to an end. The series of legal actions by Russian billionaire Dmitri Rybolovlev against the Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier ended in December 2023. However, there was still the matter of Rybolovlev’s lawsuit against Sotheby’s for allegedly aiding and abetting Bouvier in his supposed fraud. After a 21-day trial, a federal jury in New York took five hours to find Sotheby’s not liable for Rybolovlev’s damages.

The original feud between Rybolovlev and Bouvier started in 2017 when the Russian oligarch alleged that Bouvier had worked as his agent in amassing an impressive art collection. The Swiss dealer acquired thirty-eight artworks for around $2 billion on Rybolovlev’s behalf between 2002 and 2014. The most well-known piece was Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci, which later sold at Christie’s for $400 million (or $450.3 million w/p), becoming the most valuable painting in the world. Rybolovlev accused Bouvier of defrauding him of over $1 billion, and, in some cases, Sotheby’s helped him do it. Sotheby’s, of course, has denied this, asserting that it obeyed “all legal requirements, financial obligations, and industry best practices during the transactions of these artworks”.

Salvator Mundi took a central role during the trial, as it is the most well-known of the four paintings Bouvier bought at Sotheby’s, which he later sold to Rybolovlev. Bouvier purchased the work in 2013 for $83 million, turning around and selling it to the Russian billionaire for $127.5 million. Rybolovlev claims that Bouvier legally could not charge such large markups since he acted as his agent. However, Bouvier asserted that he acted as a dealer independent of Rybolovlev and could sell paintings for whatever price he wished. Sotheby’s stated that Bouvier was the only buyer to their knowledge and that whatever he did with the paintings afterward was none of their business. Sotheby’s lawyers even argued that Rybolovlev was at fault here for failing to do his due diligence and protect himself against predatory practices. In his lawsuit, however, Rybolovlev alleges that Sotheby’s was aware of Bouvier’s scheme and did nothing to prevent it. Rybolovlev’s legal team presented some evidence that Sotheby’s may have known him to be the final buyer since Sotheby’s specialist Samuel Valette viewed Salvator Mundi with both Bouvier and Rybolovlev before the purchase at the Russian oligarch’s Manhattan apartment. When called to testify, Valette stated that he did not connect Rybolovlev’s presence there to Bouvier buying the painting on his behalf. Rybolovlev further argued that Sotheby’s purposefully inflated their estimate ranges and insurance valuations to hide Bouvier’s markups.

Sotheby’s did acknowledge that Rybolovlev seems to have been taken advantage of but that it was not the auction house’s burden. Furthermore, Rybolovlev and his legal team have found a silver lining to this outcome despite the loss. They say that whether they won or not, the trial allowed the public a short glimpse into the inner workings of the art world, which are often intentionally wrapped up in secrecy. Rybolovlev’s lawyer, Daniel Kornstein, stated that the art market’s “lack of transparency” made their case so difficult to make in the first place.

For previous updates on the Bouvier Affair: