Joseph Mallord William Turner is probably one of the most beloved of Britain’s artists. He created works of art which are now recognizable symbols of the British artistic tradition, as well as pioneered techniques that would become the basis of great modern art for the next two hundred years. He was both lauded and lambasted in his lifetime, but he is now often named, along with Joshua Reynolds, John Everett Millais, Thomas Gainsborough, and John Constable, as one of Britain’s greatest painters. Today, April 23rd, is his 248th birthday.

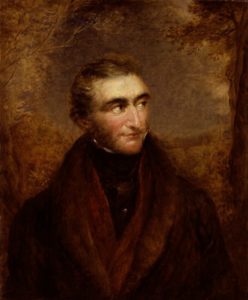

Turner was considered strange by many of his contemporaries. He was awkward and short-tempered, but most noticeably, he was not very expressive. When he did speak, he did nothing to conceal his modest, working-class London roots. He spoke with a cockney accent that some who attended his lectures at the Royal Academy considered nearly incomprehensible. But despite what some may have gathered from his appearance, demeanor, and background, for much of his career, Turner was one of the most accomplished painters of his day.

Throughout his life, Turner captured a wide variety of subjects on his canvases. In his travels across Britain and continental Europe, he filled countless sketchbooks with thousands of studies for later paintings showing ancient ruins in Rome, Swiss Alpine peaks, and packet boats moored at Dutch ports. His life spanned a turning point in the arts where Western painters were moving away from the historical and mythological subjects preferred by Rubens, Titian, and Jacques Louis David, and more towards elevating the genre of landscape painting. Sir Joshua Reynolds, president of the Royal Academy of Art when Turner entered at age 14, was known for ranking the different styles of painting in a hierarchy of quality. Despite being known primarily today as a portraitist, Reynolds listed portraiture towards the bottom of this hierarchy, along with landscapes and still lifes. It was historical paintings and genre paintings, showing scenes from history, literature, and mythology as well as depictions of everyday life, that were considered the greatest styles of the late eighteenth century. This was mainly because painters like Reynolds believed that art serves as inspiration; by offering images of Greek heroes or the virtuous yeoman of the English countryside, art should provide people with something to aspire to. Landscapes and still lifes, on the other hand, were considered simple representations of the natural world that have little complexity or deeper meaning.

But by the end of his life, Turner had elevated landscape painting to such heights that he was given the nickname the Painter of Light. His artistic career coincided with the dawning of the Romantic era, which, at least in Britain, emphasized what Edmund Burke called ‘the sublime’. The sublime refers to power and greatness, not just in the physical sense but also in the spiritual, the intellectual, and the artistic. In trying to channel the sublime, artists like Turner always strove to capture the power of the natural world, placing human beings in their proper context where nature’s monumentality dwarfs our simple goings-on. Turner did so by looking at ships on stormy seas, or clouds and fog banks rolling down a mountainside toward a hunting camp. Even when his subjects were not purely landscapes, Turner always placed nature front and center. When he did eventually dabble in creating great historical paintings, like his 1812 Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps, the Carthaginian soldiers and their elephants seem stunted in comparison to the oncoming snowstorm dominating the canvas. In his works created as a commentary on the horrors of slavery, like his 1840 painting The Slave Ship, the tumult of the sea and the brilliant, fiery hues of the sun are some of the most immediately-recognizable features of the work. However, they do not overshadow or distract from the hands of enslaved people bound in chains reaching out of the water as the ship that once carried them sails away.

Though you might not realize it by looking at his maritime scenes or Venetian cityscapes, J.M.W. Turner was far more influential than any of his contemporaries ever expected. He was constantly experimenting with new styles and approaches to painting. He was one of the first to combine the techniques of watercolor with the medium of oil paints, giving his works a light, almost ghostly or ethereal quality never seen before. Some of his paintings from his later life in the 1840s, such as Norham Castle, Sunrise and Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, were highly controversial because of the blurry quality Turner imparted to capture certain kinds of light and, in the case of the latter, to convey a sense of speed. His critics and even his patrons were incredibly confused by this new style that lacked the detail of his early work. Though contemporary critics scoffed at his works from his later life, generations of British and French artists held him in the highest regard, carefully studying his works and techniques. Specifically, French painters like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro fled to London in 1870 to escape the Franco-Prussian War, where they both came into contact with Turner’s paintings. Before then, both were only producing conventional, realist, academic cityscapes, landscapes, and still lifes. Two years after first viewing Turner’s works, Monet created Impression, soleil levant. When exhibited in 1874, it gave its name to the new style of modernist art that would later become Impressionism.

Upon his death in 1851, Turner bequeathed all the art remaining in his possession to the British nation, including around three hundred oil paintings. Today the Tate Britain boasts the greatest collection of Turner paintings in the world, with other impressive collections kept at London’s National Gallery, other museums across Britain, and several cultural institutions in the United States. A 2005 poll ranked Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire as Britain’s greatest painting, and it was selected fifteen years later to appear on the £20 note. Turner is often placed at the tail end of the Old Masters, but many refer to him as a sort of proto-Impressionist or even a forerunner of twentieth-century abstract art. Though he was considered rough-around-the-edges by some, and his more experimental art received disdain from his critics, Turner’s legacy is undeniable, and his work deserves every bit of praise and adoration it receives both in Britain and beyond.