In October, I discussed how restoration efforts on the Apollo Belvedere have recently finished. The ancient marble sculpture will be displayed at the Vatican Museums. Now, another prominent Italian sculpture will get its own makeover: Donatello’s statue of Gattamelata.

Gattamelata was the nickname for Erasmo di Narni, who became well known in northern Italy as a condottiero, or a mercenary commander. In the early to mid-fifteenth century, he led armies on behalf of Florence, Venice, and the Papacy. The name ‘Gattamelata’ literally means ‘honeyed cat’, a moniker supposedly given to him because of his charisma and persuasion skills. The Florentine sculptor Donatello spent three years creating a bronze equestrian statue in honor of the soldier, with some sources indicating that the Republic of Venice paid for it as a gift.

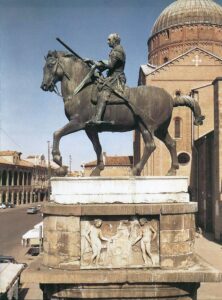

The statue is incredibly significant from an art historical perspective for several reasons. Firstly, it is one of the first major equestrian sculptures created in Europe since antiquity, with one of the only examples before Donatello being the Bamberg Rider, a stone sculpture in Germany made without little anatomical accuracy and was not made in the round. The Gattamelata statue is also the first bronze equestrian statue made since antiquity. In the thousand years between antiquity and the Renaissance, European artists neglected the process of casting bronze on a large scale to the point that the knowledge was somewhat lost. This made Donatello’s work all the more significant, not just aesthetically but technically as well. Furthermore, the statue ended up repopularizing the style of equestrian portraiture among European artists. Donatello drew inspiration from the ancient Roman equestrian statue of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, which he was able to study up close while living in Rome prior to his residency in Padua. However, in the original ancient statue, the emperor is shown as larger than life, while the horse remains life-size. It almost seems like Marcus Aurelius is riding a pony or something. With the statue of Gattamelata, Donatello made both horse and rider anatomically proportional, with the subjects’ positions and other symbolism conveying their importance instead of physical size. This was groundbreaking for the fifteenth century, especially since Gattamelata broke the norm of who received public commemoration and memorialization in Europe at the time. While public statues of religious figures and the nobility or royalty were normal, Gattamelata was born a commoner who rose up through the military to conquer and rule cities in northern Italy on behalf of Venice. It is not only one of the great works of the early Renaissance, but it has become a symbol of Padua’s cultural and civic pride. And now, at over 570 years old, the early Renaissance bronze is in dire need of some restoration.

Recent tests have revealed some severe corrosion of the bronze, highlighting the urgent need for restoration. The stone plinth supporting the statue also requires attention to ensure its stability. The Pontifical Delegation to the Basicila di Sant’Antonio, outside of which the statue is displayed, is one of the main organizations spearheading the restoration efforts. The University of Padua’s Interdepartmental Archaeology, Architecture, and Art-Historical Research, Study, and Conservation Center (CIBA) will also be contributing towards Gattamelata’s conservation, along with several nonprofit cultural organizations like Save Venice and Friends of Florence. Father Antonio Ramina, rector of the Basilica di Sant’Antonio, commented, “With the generosity of the two American foundations, [the restoration] translates into concrete action the belief in the universality of cultural heritage’s value to humanity entire regardless of where it is.” To fully study the statue, it will need to be temporarily relocated to a place where specialists can easily access it and also protects it from the elements. Friends of Florence have enlisted the help of restorer Nicola Salvioli, who worked with the organization to restore Lorenzo Ghiberti’s baptistry doors, known as the Gates of Paradise. Of the entire Gattamelata statue, the horse itself seems to be the top priority for the restoration efforts, as its slender legs have grown steadily weaker over the centuries and may not be able to support the entire 3,400-pound statue. Padua’s cultural councilor, Andrea Colasio, said it constitutes “the first element of a larger, systemic puzzle”. Some speculate that the work on Gattamelata will likely serve as a place where new conservation practices and methodologies could be tested, setting new standards for the future of bronze sculpture restoration.