In 2020, the British Museum hosted an exhibition called Inspired by the East, delving into how the Islamic world made its way into Western art. Writing for Hyperallergic, Aditya Iyer described the exhibition as a “worthwhile but flawed” attempt to “extract Orientalist art from its sinister role in fostering Western perceptions and depictions of the East”. While Iyer admits that the paintings and artifacts in the exhibition are beautiful, the British Museum failed to fully acknowledge the art’s complex history. The exhibition recognized that many see Orientalism as problematic, but it failed to address why that is. They thought that the paintings could speak for themselves. But why is Orientalism considered problematic? Is it okay to like it? And, if so, when is it alright?

According to Oxford Languages, Orientalism is “the representation of Asia, especially the Middle East, in a stereotyped way that is regarded as embodying a colonialist attitude.” Note how the dictionary definition, right up front, acknowledges the negative connotations attached to the word. Orientalism has been with us for centuries, stretching from Old Master paintings to Disney films like Aladdin. And even though it’s often easy to hide behind excuses like, “It’s just a painting,” the purpose behind a work’s creation and the context in which it was made and exhibited is just as important as its subject. The genre of Orientalist art sometimes twisted, exaggerated, and fetishized the people, culture, and places of the Middle East and North Africa, reinforcing stereotypes about the region that justified the colonial endeavors of European empires.

In the nineteenth century, Orientalist art was popular in Europe because of two converging factors: exoticization and colonialism. Exoticization is the natural human interest in the other or the unknown. Even though locations like Algiers and Cairo were just across the Mediterranean from Western Europe, the differences in climate, culture, language, and religion made the Middle East and North Africa seem so distant. These differences were so great that the region could be used almost as a backdrop for pure fantasy. In wanting to provide a certain aesthetic, many Orientalist artists would often draw not from travelogues or the writings of anthropologists, but their own imaginations. The best example is Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer, which mainly uses meaningless scribbles as a stand-in for Arabic calligraphy on the wall. This is not unique to The Snake Charmer and is a phenomenon in Orientalist art that Nesrine Malik described as “pseudo Arabic that used the script to lend authenticity, but is in fact a clumsy imitation of loops and lines that are unintelligible.” But this is just one of the painting’s many eyebrow-raising characteristics. “The East” in these artists’ minds was wild, mystical, and brutal compared to the cultured, educated, proper “civilization” they came from. In The Snake Charmer, we see a boy displaying a snake to entertain a group of men. The boy is completely naked, with a lack of clothing hinting at the region’s perceived licentiousness. The men are all reclining on the floor, backs against the wall, conveying a sense of idleness. But very importantly, the painting has an aura of mystery, a key component of Orientalism. The art historian Linda Nochlin writes that through The Snake Charmer, Gérôme provides “an unrealistic scene as if it were a true representation of the east.”

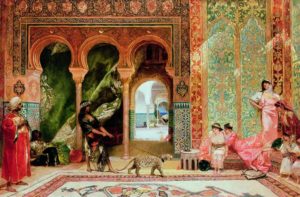

The setting of the East gave European artists liberties they would not have otherwise enjoyed. For decades, Orientalist painting was the only artistic genre where overt sexuality of any kind was permissible. Of course, nudes were commonplace in European academic art, but not in the same way as in Orientalist paintings. In academic art, nudes were reserved for mythological subjects and allegorical figures. But in Orientalism, painters depicted women of any kind in an inherently sexual way that would have been scandalous if applied to a woman of the artists’ own countries. The sexualization of Middle Eastern and North African women stems partly from European perceptions of the Ottoman upper classes and their practice of keeping harems. The harem was simply the women’s quarters of the household, but in the European imagination, men always used it to keep their flock of wives and concubines. It reached the point that any Orientalist-inspired nude painting bore the title odalisque, the French approximation of the Turkish word for a chambermaid, odalık. An odalık employed in an Ottoman household was not a concubine, yet they were perceived this way in Europe, particularly in France. The sexualization of the region’s people gave rise to the odalisque genre of nude figure painting, which only reinforced further sexualization. Art historian Nicholas Tromans wrote that the odalisque was meant to be “offered up to the viewer as freely as she herself supposedly was to her master”. Nineteenth-century painters like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Frederick Arthur Bridgman all indulged this urge. The region’s perceived barbarity collided with this sexualization through Orientalist art’s fixation on slavery. By the mid-nineteenth century, most European states had outlawed slavery, with treaties and alliances formed to prevent the slave trade. At the same time, the nude enslaved woman became a popular subject among European Orientalist painters like Otto Pliny, Fabio Fabbi, and Giulio Rosati. Gérôme was probably the most prolific painter of Orientalist slave scenes, namely slave markets. Combining sex and savagery, these paintings’ female subjects are always completely passive, with no other role than being the focus of the male gaze.

Depictions of men in Orientalist paintings are a little more complicated as they come in one of two main varieties: the warlike and the devout. Men are either shown as heavily armed regardless of their situation, or in a mosque setting, normally on their prayer mat. Writing for The Guardian, cultural critic Nesrine Malik acknowledges that this is one of the interesting aspects of the genre that the British Museum tried to highlight in its 2020 exhibition. Alongside a lot of the racist clichés, Orientalist paintings also showed how Europeans perceived Islam as a religion. It often ranged from fascination to admiration. The piety shown in paintings like The Prayer by Frederick Arthur Bridgman was something admirable, and how shameful it is that Western perceptions of Islam have changed so much in a radically different direction, one associated with extremism and violence. Malik wrote, “If the orientalism of the past was patronising fetishisation, it is still a far more respectful perspective than the fearful one that predominates today.” However, since Europeans saw the Middle East and North Africa as inherently mystical yet wild and uncivilized, these forms of exoticization led to the other main reason Orientalism remained popular in the nineteenth century: colonialism.

With advances in communication and transportation technology, the nineteenth-century world grew more interconnected with each passing year. Parts of the globe that seemed far-flung were more readily accessible for Westerners because European nations began exerting direct control in these areas. France seized control over Algeria in 1830, holding onto it for over one hundred thirty years. Though nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, Egypt was a British protectorate from 1882 until the Suez Crisis in 1956. Even into the twentieth century, European colonial powers jockeyed for control of the region, with the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement laying out how Britain and France carved up the Ottoman Empire after its defeat in the First World War. This colonial context significantly influenced the creation and reception of Orientalism. This art, in turn, came to shape Western perceptions of the East.

It is very important, however, to distinguish between this problematic context and problematic subjects. All Orientalist paintings have associations of colonialism attached to them. Eastern subjects would not have become popular had it not been for French and British colonization bringing these locales into the public imagination. But as long as we recognize the problematic context, we can still enjoy a painting as long as the subject does not reflect racist stereotypes. It’s easy to say that nearly everyone was racist in the nineteenth century, but that clearly isn’t as true as it seems. Many Western painters approached Eastern subjects without resorting to such offensive generalizations, creating works we can still enjoy today. John Frederick Lewis, for example, did what not many of his Orientalist contemporaries did and moved to the region. While Delacroix and Ingres created their odalisques without ever visiting Egypt or Algeria, Lewis lived in Cairo for nearly ten years, making detailed genre scenes and interiors showing episodes from daily life. Lewis refrained from applying a layer of sexualization to his female subjects, using his wife as a model to show scenes of Egyptian women preparing and serving coffee or spending leisure time in the garden. Lewis and some other painters depicted the household women’s quarters closer to how they actually operated: less a place of concubines and more “a place of almost English domesticity,” according to Tromans. Even art historian Philippe Jullian admits that among the bare-breasted harem slaves other Orientalists preferred, the women in Lewis’s paintings stand out: “But only a perverse mind would be suspicious about the delightful Egyptian women, painted by Lewis”. As an English painter depicting Eastern subjects, Lewis still indulged the Western demand for exotic subjects. But at least he and others show that these paintings do not need to employ such heavy-handed clichés. His work later inspired like-minded Orientalist painters like Edward Lear, who focused mainly on landscapes and architecture rather than sensationalized scenes of savageness and sex. Lewis’s French contemporary, Charles-Théodore Frère, also created wonderful Orientalist landscapes, gaining fame for capturing the light over the Nile at different times of the day.

But even in this relatively inoffensive variety of Orientalism, we still must contend with some problematic aspects. Again, colonialism was one of the major reasons why even these landscapes and genre scenes had a market in Europe. But it also presents the problem of agency. By capturing the look and feel of the Islamic world from Morocco to Turkey, European artists were doing something they believed the region’s people were incapable of doing themselves. In the same way that the racist stereotypes reinforced European notions that Middle Eastern and North African people could not effectively rule themselves, these artists took agency away from the region’s people to represent themselves artistically. Of course, it’s not that Islamic artists could not represent themselves; they simply chose not to. With exceptions like Iran, much of Islamic art follows the rule of aniconism, refraining from depicting human figures. Instead, most Islamic art focuses on calligraphy, geometric patterns, and natural motifs. Architecture was also one of the main art forms, so beautiful that even the reconquering Catholic armies in Spain could not fully bring themselves to tear the buildings down. That is why structures like the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the Alhambra, and the Alcázar of Seville still stand today. So, scenes from history and daily life were not normally a priority for artists in the Middle East and North Africa.

But luckily, some Eastern artists recognized that Orientalist art was often rife with misconceptions and clichés. Several of these Eastern artists fought back in their own way. Among the best-known of these artists is the Ottoman painter Osman Hamdi Bey, who studied art in Paris under Gérôme. He mastered European painting techniques to create authentic snapshots of life in Turkey. He depicted his female subjects without any added exoticization or sexualization. The women in his paintings wear traditional clothing as opposed to the scantily clad dancers and concubines of Otto Pliny, Edwin Long, and Théodore Chasseriau. Also, they are not all simply lounging about in a harem or a bathhouse. Rather, they read, socialize in public, gather flowers, and perform other tasks. Hamdi even created paintings showing Western tourists in an Eastern setting, like in The Persian Carpet Dealers. Furthermore, the men are not savages, constantly bearing rifles and scimitars, but they are not always in a mosque setting either. They are scholars and enjoy leisure activities like chess. His paintings also often have deeper messages, serving as social commentary. Arguably, his most famous painting is The Tortoise Trainer, showing an older man in traditional Ottoman dress trying to control a group of tortoises, who ignore him and prefer to focus on the leaves on the floor. Many interpret the painting as a metaphor for the difficulties of implementing social and political reform in the Ottoman Empire. Hamdi’s 1903 painting Keeper of the Mausoleum has another hidden message. The work shows a man, again in traditional Ottoman dress, standing guard over a tomb containing a pair of children’s sarcophagi. Some interpret the painting as another metaphor representing the desire to preserve and maintain Ottoman cultural heritage. Hamdi’s paintings were not just well-executed scenes of Ottoman life but a concerted effort to combat some of the more hurtful stereotypes present in some European Orientalism. Sotheby’s nineteenth-century specialist Harry Edmonds described Hamdi’s work as “aesthetic constructions designed to attract the attention of a Western public by combining clichés intelligently with the privilege of being an ‘insider within the outside.’”

To many, the context in which European artists made Orientalist paintings is incredibly uncomfortable. The question then becomes, do we fully recognize the racism and the troublesome context of even the most inoffensive Orientalist painting? Or do we brush it under the rug for the sake of enjoying a painting, or make it more appealing to buyers? No one is saying that Orientalism should be entirely rejected or wholly accepted without any caveats or conditions. There’s nuance to this conversation, which unfortunately requires extra effort that some are unwilling to put in. I think it’s a balancing act. The problematic qualities of some paintings are insufficient to outweigh their aesthetics or artistic merit. However, there are others where it is the opposite, and our modern sensibilities keep us from enjoying particular paintings regardless of the artist’s skill. With the world now more interconnected than ever, it becomes increasingly important to have these conversations. These paintings teach us valuable lessons about cross-cultural exchange, art’s impact on geopolitics, and how choices made centuries ago can still influence our modern perceptions of people and places. While one’s stance in this debate is their own, the important thing is having this debate in the first place.