In my series on the origins of modern art, I’ve looked at the predecessors that influenced the birth of Impressionism. The topics I’ve covered include the desire for greater artistic independence as exhibited by Gustave Courbet, the ways Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres experimented with abstraction, and how J.M.W. Turner helped elevate landscape painting to a genre worthy of respect and admiration. On that last note, Turner was incredibly influential on Impressionist painters like Monet and Pissarro. But on top of Turner’s landscapes, the Impressionists were also greatly inspired by the landscape painters of their own country, known as the Barbizon School. This earlier generation of French landscape painters pioneered painting en plein air, one of the key components of Impressionist painting. This is the Barbizon School, the environmentalist painters who paved the way for modern European art.

Until the Barbizon School, landscapes were a very different genre of painting. The art historian Steven Adams refers to pre-Barbizon landscapes as employing a “stage-managed approach”. For several centuries, landscape paintings were often not truthful depictions of nature. Rather, they were settings for biblical and historical subjects. Painters like Poussin and Lorrain popularized the genres of classical or historical landscape, creating entirely fictional natural backdrops for gods, heroes, prophets, and warriors. The closest forebears to the Barbizon painters were the seventeenth-century Dutch landscape artists like Jacob van Ruisdael and Aelbert Cuyp, whose conventions had gone by the wayside until revitalized by British artists like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable. By the 1820s, the Salon had only recently begun accepting Romantic paintings on top of traditional academic and neoclassical art. They were not, however, willing to give credit to landscapes and similar art forms, as they were considered mere imitations of the natural world without any messages or ideas baked into them.

The true story of the Barbizon painters starts earlier in the nineteenth century. First, in 1817, the Académie des Beaux-Art introduced a category in the Prix de Rome, one for paysage historique, or historical landscape. This led to renewed interest in landscape painting as a genre. Then, in 1824, the British landscape painter John Constable exhibited some of his work at the Paris Salon. Most famously, he showed his 1821 painting The Hay Wain, which King Charles X awarded a gold medal. Several other British artists exhibited at the Salon that year, including David Wilkie and Thomas Lawrence, with their work becoming far more popular in France than in their native country. Many young French artists at the time saw Constable’s paintings as almost revolutionary, pushing them out the studio door and into the open air. These young painters became driven to go out into nature, experience its sublime power, and distill it into a moment they could put to canvas.

Since most of these artists were based in Paris, there were few nearby places they could visit for inspiration; though there was one area they could go: the forest of Fontainebleau, just southeast of the French capital. On the forest’s border was a small village called Barbizon, where these young painters would stay. Some artists, like Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, had already been experimenting with landscape painting before Constable’s work showed up at the Salon. However, with this final push, he and many of his contemporaries like Charles-François Daubigny, Constant Troyon, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, and Théodore Rousseau flocked to this village, mainly staying at an inn called the Auberge Ganne. Today, the inn is a museum, displaying its old registry filled with the names of many of France’s great nineteenth-century artists.

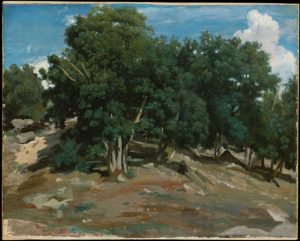

At first, these young painters made their landscapes cautiously and conservatively, going out into the forest every day to make studies and sketches before creating a completed composition in a studio. But some painters later broke these conventions, trying to complete a painting in as few sessions as possible. To do this, they had to take their canvases and paints into the forest to paint outside, or en plein air. Completing an entire painting outside was a revolutionary new technique. The Barbizon artists used it to best capture the landscape as a whole rather than focus on its component parts. This practice also resulted in the Barbizon painters focusing less on finer details. For example, Corot caused a scandal after submitting the painting Fontainebleau: Oak Trees at Bas-Bréau to the Salon. The brushwork was loose, with whole sections having minimal detail. To the academic conservatives, it seemed hastily done. To the younger generation, meanwhile, it represented a new sense of spontaneity not yet seen in European fine arts. It was actually the works of painters like Corot, Daubigny, and some other Barbizon artists to which the term “impression” was first applied. It would be revived to criticize the next generation of artists, only this time the name stuck.

The Barbizon painters only started to gain wider acceptance around 1830. This is why, in the French-speaking world, these artists are not called Barbizon; rather, they are referred to as the School of 1830. This connects them to the political upheaval in France at the time, which saw the second and final overthrow of the Bourbon kings in favor of the liberal monarchy of King Louis-Philippe. With political change, the French public became more accepting of cultural and artistic change. This mirrors how the 1848 Revolution that overthrew Louis-Philippe is often connected to the birth of Realism pioneered by Gustave Courbet. Many artists saw the increasing popularity of landscape painting as connected to greater political liberalization and the push for democracy. The Salon that year and throughout the early 1830s included paintings inspired by the revolution, like Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, Philippe-Auguste Jeanron’s Les Petits Patriotes, and Hippolyte Lecomte’s Combat de la Porte Saint-Denis. This was when some of the early Barbizon paintings were exhibited as well.

Originally, the painters would flock to Barbizon to stay for part of the year. But in the 1840s, artists like Rousseau and Millet would permanently move to the village. There, each of the painters went down their own path. Despite Rousseau’s initial Salon successes, the academy juries later rejected his work the more time he spent in Barbizon; between 1836 and 1841, all of his works submitted to the Salon were rejected. This led to the artist’s nickname, le Grand Refusé, or the Great Reject. At this point, he retreated into the forest, creating landscapes that focused on the subtleties of light at certain points in the day. His 1845 painting Hoar Frost is probably his best-known example of this practice. In doing so, Rousseau became a forerunner of the Impressionists, specifically Claude Monet, who would make several series of paintings focusing on the same subject under different weather and light conditions.

While Rousseau focused strictly on nature itself, other Barbizon painters would incorporate figures to populate their canvases. Constant Troyon and Jules Dupré often featured livestock and other animals, giving the scenes a pastoral feel while refraining from adding too many human elements. Such work would likely impact genres like animal painting, pioneered by Rosa Bonheur. Meanwhile, Jean-François Millet became influenced by Courbet’s Realism, incorporating scenes of French peasant life into his work. By doing so, Millet became particularly influential on the two main diverging branches of painting: Impressionism and Academicism. Of course, he became an example of a painter who goes out into the world and paints it as he sees it. With technological improvements like collapsible paint tubes, the Impressionists followed this example and went out into nature to capture a moment as quickly as possible. His unvarnished, Realist looks into the difficulties of rural life also served to show that great art did not have to focus on elevated subjects as the academic painters did. However, in his focus on scenes of French peasant life, Millet would actually come to influence later generations of academic painters like Jules Breton, Julien Dupré, and Jules-Alexis Muenier. These academics would apply traditional techniques to genre paintings. By looking at his most famous work, The Gleaners, one can see how his style and choice of subject impacted both Impressionist and academic painting.

Although their influence on modern art is what they are primarily known for, the Barbizon painters’ activities also had another consequence. The forest of Fontainebleau was the Barbizon painters’ preferred subject. These painters formed a connection with the area’s landscape that most Parisians did not have. Because of their prolonged relationship with the area, many noticed the changes taking place there in the form of people cutting down old trees and planting new ones. These artists objected to any alteration to the landscape, forming the Association des Amis de la Forêt de Fontainebleau (AAFF) in 1839. Working in tandem with Claude-François Denecourt, the Barbizon painters and the AAFF managed to get over 6,000 square kilometers of forest protected as part of a nature sanctuary in 1853, designated off-limits to timber operations. Later, in 1861, an imperial decree issued by Napoleon III designated close to 11,000 square kilometers of the forest as a “réserve artistique”. Thanks to their efforts, Fontainebleau became the world’s first nature reserve, predating the foundation of Yellowstone National Park by eleven years.

By the 1860s, the Barbizon painters were now established artists when a new generation of painters emerged. Like their idols, these younger painters went to paint in the forest of Fontainebleau, staying at the Auberge Ganne and trodding some of the same ground as their predecessors. Artists like Monet, Renoir, and Sisley all got their start by trekking off and painting the forest, mastering the art of Barbizon painting before heading off in their own direction. They took Barbizon techniques further, developing them into Impressionism, kickstarting most forms of modern art in Europe. Without them, we would have no Van Gogh or Gauguin, nor would we have Picasso, Rothko, or Basquiat. They may seem like simple, quaint landscapes nowadays, but it’s important to remember how something so simple could result in something revolutionary.