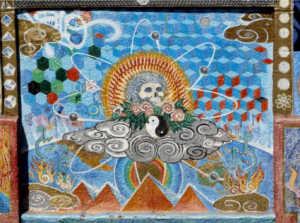

When we think of the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, a very specific image often comes to mind: a beautiful woman with long hair in a flowing, formless dress surrounded by flowers. There are also the central ideas that accompany such an image, like free love, spiritualism, and rejection of the establishment. This was made possible by many different factors converging in the prosperous post-war period. However, it may not be easy to see how a band of Victorian painters could be some of the earliest forebears of hippie culture. Yet, it’s true. In 1848, a group of young British artists styled themselves as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This collection of artists formed the core of Britain’s first modernist art movement, exerting influence in their own time and beyond.

The main impetus behind both Pre-Raphaelite art and the counterculture was a rejection of authority. The leading Pre-Raphaelite artists met while studying traditional, academic art at London’s Royal Academy in the 1840s. The painters William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti are the most well-known today, but the group consisted of seven. It also included the painter James Collinson, the sculptor Thomas Woolner, and the critics Frederic George Stephens and William Michael Rossetti, brother to Dante. But the style was not restricted to this core group. Many other British artists would come to adopt Pre-Raphaelitism, including Edward Burne-Jones, Marie Spartali Stillman, John W. Godward, and John William Waterhouse. Pre-Raphaelitism, however, is best explained by what it was not rather than what it was. It was a reactionary art movement, with these young artists unified not by a common goal but a common enemy. They were incredibly disenchanted by the conservative styles of art taught at schools like the Royal Academy, aiming to break conventions and bend rules. They used greater detail, employed vivid colors, and emphasized symbolism and meaning in their work, leading them to draw inspiration from poetry and literature.

But why were they called Pre-Raphaelite? The group chose the name because the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century academic art establishment venerated the Italian Renaissance master Raphael. All the great painters who came after Raphael were, in their view, nothing but imitators, sacrificing their own path as artists to live up to his standards of beauty and form. In rebelling against academic painting, the Pre-Raphaelites chose to look back before Raphael to the Quattrocento, or fourteenth-century Italian art. Late medieval aesthetics in stained glass and illuminated manuscripts greatly appealed to them, as did the relative simplicity of Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Verrocchio, and Mantegna. The art critic John Ruskin, one of the Pre-Raphaelites’ most ardent defenders in the press, dismissed the critics who disparaged the Pre-Raphaelites for attempting to revive what they saw as archaic art. Ruskin wrote that these artists “draw either what they see, or what they suppose might have been the actual facts of the scene they desire to represent, irrespective of any conventional rules of picture-making”. He argued that the Pre-Raphaelites did not want to revive older art forms entirely but rather bring back what they saw as sincerity and realism. They were not imitators; rather, the conservative art establishment was imitators, aspiring for three centuries to paint like Raphael and follow his example.

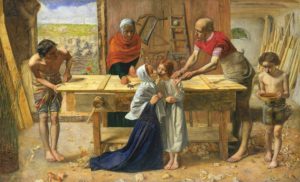

The Pre-Raphaelites first exhibited their paintings in 1849, and most critics were absolutely brutal. They saw their work as subversive, contrary to academic art conventions. When Millais exhibited Christ in the House of His Parents the following year, Charles Dickens was particularly harsh in his assessment. He described Millais’s Virgin Mary as “so horrible in her ugliness, that […] she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England.” An article in The Times described the artists as having “absolute contempt for perspective and the known laws of light and shade, an aversion to beauty in every shape, and a singular devotion to the minute accidents of their subjects, including, or rather seeking out, every excess of sharpness and deformity.” Furthermore, some critics and exhibition-goers believed that drawing from medieval and early Renaissance elements gave Pre-Raphaelite painting a distinctly Catholic aesthetic. British Catholics only got increased civil and political rights in 1829, but anti-Catholic sentiment remained as high as ever. One writer in The Times described Pre-Raphaelite paintings as “monkish follies”, with even their defenders like Ruskin admitting that they regrettably displayed some “Romanist and Tractarian tendencies”. It is this spirit of rebellion that fueled both the Pre-Raphaelites and the later counterculture, with the paintings of the former echoing or even inspiring the aesthetics of the latter.

Anyone looking at Rossetti’s models like Elizabeth Siddal, Jane Morris, or Fanny Cornforth can see the typical hippie woman. Additionally, paintings like Waterhouse’s Lady of Shalott and Burne-Jones’s Aurora show the subjects’ long hair and flowing dresses, echoing medieval romances and foreshadowing the rise of later countercultural attitudes. This influence was not limited to just women, though. Male countercultural figures like Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones sometimes opted for more formless clothing dominated by vivid colors, vibrant patterns, and floral motifs that echoed those found in works by Hunt and Rossetti. However, while fantasy and medievalism impacted both the Pre-Raphaelites and the counterculture, the greater influence was Orientalism. Like other nineteenth-century European artists, the Pre-Raphaelites were incredibly fascinated with “the East.” The rise of European colonialism made far-flung locales seem more accessible. Thus, painters like William Holman Hunt traveled to the Middle East to look for subjects and ways to improve their art. Hunt used his travels to collect information on the people and customs of the Levant to inform his design of Orientalist and biblical paintings like The Scapegoat, Finding the Saviour in the Temple, and The Shadow of Death.

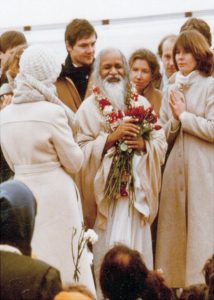

The counterculture’s own Orientalism grew from young people’s disenchantment with existing power structures. They explored non-Western religions and spiritualist practices, particularly those from South and East Asia, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Daoism. While there isn’t a clear connection between Pre-Raphaelite Orientalism and the hippies’ spiritual experimentation, one can see common root causes: a fascination with the unfamiliar and the exotic, looking beyond the bounds of their own society for inspiration. Though separated by a century, both groups looked to the East because of the constraints imposed by conformity.

Also similar to the 1960s counterculture, the Pre-Raphaelites enjoyed a stronger connection to nature than their contemporary academicians. In one of John Ruskin’s defenses in The Times, he wrote about the painting Convent Thoughts by Charles Allston Collins, focusing on how the artist depicts flowers. Most critics, according to Ruskin, “say sweepingly that these men ‘sacrifice truth as well as feeling to eccentricity.’ As a botanical study of the water lily and Alisma, […] this picture would be invaluable to me, and I heartily wish it were mine.” The Pre-Raphaelites, like the Romantics before them, strove to channel a connection to nature through their work. Romantic and Pre-Raphaelite artists both believed in having a profound appreciation of the natural world because of its enormity relative to human creation. These artists and the later hippies saw nature as something to live with rather than fight against. Both groups were reacting to processes like urbanization and industrialization at different stages, and created a material culture dominated by natural elements and motifs. This is why hippies were also known as flower children, and the nonviolent forms of protests they organized came with the slogan “Flower Power.” Meanwhile, the Pre-Raphaelites combined their connection to nature with their attention to detail, leading to many artists using natural elements carefully and intentionally. They would use specific kinds of plants and flowers to convey messages about their work. In the painting, Ophelia, John Everett Millais includes daisies representing innocence, pansies representing love in vain, and poppies representing sleep and death.

Speaking of the poppy, drug use in the counterculture of the 1960s was often a voluntary way of expanding one’s mind or altering one’s consciousness. In Victorian England, drug use was prevalent, though used very differently. In the early to mid-nineteenth century, opium imported from Turkey was used mainly for medicinal purposes. The advent of the Pre-Raphaelite style coincided with a boom in the opium trade in Britain. Imports grew sixfold between 1830 and 1860 while prices steadily decreased, making it more readily available. Some scholars like Suzanne Bode theorize that the widespread medicinal use of opium in nineteenth-century Britain influenced the way the Pre-Raphaelite painters created their works and impacted the way Victorian audiences interpreted them. Opium use reduces the size of the pupil and affects the way we perceive light and depth. According to Bode, the Pre-Raphaelite artists “were reproducing this physiological effect to create the unsettling, colorful, and surreal spaces of their paintings.” These artists also used opium’s place in the public consciousness to convey themes of sleep and death (like in Ophelia). Elizabeth Siddal is primarily known as Rossetti’s muse and model, but she was also an artist in her own right. On top of that, she was an opium addict. Many believe that though she took opium to relieve physical and psychological pain, she was fully aware of the effect it had on her senses and how it influenced her art. This was not unusual for the time, as her contemporary Elizabeth Barrett Browning was also known to have been a functioning addict, using drugs like opium to fuel her creativity. In the Siddal biography The Wife of Rossetti, written by William Holman Hunt’s daughter Violet, Rossetti was drawn into the world of casual and recreational drug use, which would later lead to his death at the age of 53 in 1882. Similar to the Pre-Raphaelites’ use of opium, recreational drug use became common within the counterculture. Countercultural artists used cannabis and hallucinogens in the same way that Rossetti, Siddal, and Millais altered their senses with similar substances.

On top of drug use, other aspects of the Pre-Raphaelites’ personal lives also courted controversy. Dante Gabriel Rossetti was divisive in his own time due to his many affairs with his models. Rossetti is almost a forerunner to the concept of free love that became commonplace in the 1960s. These attitudes on love, sex, and relationships likely came from his mother’s family, as his uncle John Polidori was a colleague of Lord Byron, Mary Shelly, and Percy Bysshe Shelly, some of Britain’s foremost Romantic literary figures and advocates of free love. Rossetti’s most famous affair was with Elizabeth Siddal, who had modeled for many of his paintings and drawings starting in 1850. By 1854, the pair were living together in London, which was controversial since they were unmarried, not doing so until 1860. Rossetti also had a prolonged affair with Jane Burden Morris, the wife of his friend William Morris. Though Rossetti tried to keep his passions hidden, he used Morris as his model so often that things became clear to her husband. Rather than confront the pair, Morris allowed the affair to continue, leasing a country house for them to use while he was away. Rossetti was definitely the most lascivious of the Pre-Raphaelites, but he was far from the only one to lead an unconventional personal life. A good amount of controversy surrounded John Everett Millais’s marriage, as his wife Effie had previously been married to John Ruskin. The annulment of the Ruskins’ marriage and Effie’s subsequent remarriage to Millais caused a scandal. The idea of this possible love triangle fascinates people even today.

A mural in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco that shares several qualities with Pre-Raphaelite art (vivid colors and patterns, nature/floral imagery, Orientalist components, etc.)

As their careers progressed, many Pre-Raphaelite painters paved the way for twentieth-century styles like symbolism and Art Nouveau. They also influenced artists outside of Britain, as the American painter James McNeill Whistler more or less created his own Pre-Raphaelite woman in his painting Symphony in White, No. 1 exhibited at the 1863 Salon des Refusés. But it wasn’t just the symbolists and other modernists that the Pre-Raphaelites influenced. One can link these Victorian painters to the counterculture of the 1960s. They profoundly impacted the counterculture’s look, achieved mainly through Pre-Raphaelite influence on 1960s art. However, this was not painting or sculpture but more popular and accessible art forms like album covers and posters. British designers like Michael English and Nigel Waymouth actively pulled from nineteenth-century art, specifically Pre-Raphaelite and Orientalist paintings, to create their designs for posters advertising London nightlife spots like the UFO Club.

It can be easy to paint with a broad brush in characterizing groups of people. While the Victorian era has a reputation for being stuffy and prudish, it’s good to remember that there were bright, lively exceptions. As such, the Pre-Raphaelites not only shared many similarities with the counterculture a century later, but in some ways would directly influence its look and its major components. It’s a lasting legacy that has continued up until the present day.