How did Gustave Courbet, a bohemian, revolutionary communard, lay some of the groundwork for modern art?

I’ve written several times about the origins of modern art. Specifically, I enjoy looking into the lives of modernism’s progenitors, those artists who helped pave the way for later generations. Previously, I’ve discussed several of these figures, including the British landscape painter J.M.W. Turner and the French neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. I’ve also written about the Paris Salon and how its desire for uniformity and to create an objective sense of artistic taste resulted in working artists seeking greater independence. However, this is where the story of an artistic forebear and the desire for creative autonomy merge into one. This is the story of the Realist revolutionary Gustave Courbet, with his life and long-lasting legacy summed up in five of his paintings.

#1 – Courbet the Newcomer: After Dinner at Ornans

Courbet was originally from Ornans, a small French town close to the border with Switzerland. In 1839, he arrived in Paris. Only 20 years old, Courbet spent his days at the Louvre, making studies and copies of the Spanish and Flemish paintings on display. He saw the works of the Old Masters like Rembrandt and Velázquez, who often approached their subjects in a refreshingly candid fashion. This is how Courbet learned to draw, sketch, and paint, essentially teaching himself… or at least, that’s what he said later. Courbet consciously created a persona, taking on the role of a self-taught country boy. However, he was not a simple peasant by any means. His father Régis certainly had humble roots but rose to become a wealthy landowner. Courbet received his artistic training in a rather conventional way. He attended the royal college at Besançon, studying drawing and painting under Charles-Antoine Flajoulot, a pupil of Jacques-Louis David. For those pursuing a career in the arts in the nineteenth century, one would work as an apprentice or an assistant to an established artist after leaving school. Courbet did this by traveling to Paris and working as the studio assistant for Charles de Steuben, known mainly for historical and religious paintings.

But even though he had parts of a conventional artistic education, Courbet was still fiercely independent, taking control of his artistic development as he saw fit. Insisting that he carve out his own path led him to what defined his career as an artist: his art’s purpose would be to capture the experience of everyday life. While genre painting was nothing new, the Academy juries had not accepted it as a style worthy of high praise like large-scale history and religious works. This custom certainly explains why juries would so frequently reject Courbet’s work for exhibition during his first years in Paris. The Academy jury rejected twenty-two of the twenty-five paintings he submitted up until 1848.

After years of submissions, however, Courbet’s first great Salon success came in 1849, when his painting After Dinner at Ornans won a gold medal and was purchased by the state. This was rather surprising because it was a controversial work at the time. It was not controversial because of the subject matter or the artistic technique but rather because of its size. After Dinner at Ornans was created on an incredibly large canvas, measuring over six by eight feet. This was the kind of canvas typically reserved for more esteemed styles of painting showing biblical scenes or great moments from history. This monumentalization of the mundane was a habit Courbet would continue for much of his early career. The British art historian William Vaughan noted that Courbet did this “to emphasize that the painting of the everyday was important, and not just that it was an interesting subject but that it was as important as any kind of painting.”

With After Dinner at Ornans, Courbet stepped out into the larger art world and offered something new and exciting at a time when French art had grown somewhat stagnant. For about twenty years, the French art scene had been divided into camps of Romanticists and Classicists, something I’ve touched on previously in looking at the career of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. With his scenes of the everyday transferred onto monumental canvases, Courbet brought a fresh jolt of energy to the Salon. With his gold medal, Courbet was awarded the special privilege of being exempt from the requirement to submit his paintings for approval by the Academy jury. He would only lose this privilege when they changed the rules in 1857.

#2 – Courbet the Realist: The Stone Breakers

After his first Salon success and the privileges that accompanied it, Courbet decided it was time to ruffle some feathers and break some rules. Or rather, break some stones. In 1850, he submitted nine paintings to the Salon, including A Burial at Ornans. It is the painting The Stone Breakers, however, that best exemplifies Realist art. While traditional genre painting often drew on everyday life, The Stone Breakers broke many of the style’s conventions. When showing scenes of peasant life, most continental European painters would depict an idealized version of rural attire and work. The genre scenes of previous generations would often show peasants either as stoic figures in very clean traditional clothing dutifully carrying out their work, or as revelers frequenting a tavern or celebrating at a wedding or a festival. They were either symbols or caricatures rather than real people. These conventions would continue well into the nineteenth century, especially among European academic painters like Bouguereau, Munier, and Blaas. They aimed to create a more idealistic version of rural Europe as a counterweight to the continent’s increasing urbanization and industrialization.

However, the two men in Courbet’s Stone Breakers stand out entirely. They are wearing dirty clothes and wooden clogs, signs of poverty. Furthermore, the subjects’ task of breaking rocks in the middle of a country road is not noble, like driving a plow or harvesting wheat. It is dull, repetitive, menial work, similar to the industrial labor becoming more common in France’s cities at the time. Courbet was one of several artists who began to eschew working peoples’ idealization. Others like Jean-François Millet and Philippe-Auguste Jeanron had previously indulged the artistic urge to romanticize French peasants but, like Courbet, were turning towards strict Realism. Courbet and these other artists saw that to be the best painters they could be, they had to paint what they themselves saw and experienced. In an 1855 exhibition catalogue, Courbet wrote that his goals as an artist were to “translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my time, according to my own estimation; to be not only a painter, but a man as well; in short, to create living art – this is my goal.”

#3 – Courbet the Independent: The Painter’s Studio

Courbet was not afraid to send messages through his paintings. In capturing the lives of his own time’s working people, Courbet made statements on social issues of the day. He would bring this style to a larger audience with the 1855 World’s Fair. For the fair’s arts section, the Académie des Beaux-Arts curated an exhibition of work from many of the giants of French painting, including Delacroix and Ingres. However, many artists were excluded, including some who, though young at the time, would later become the pioneers of artistic modernism, like Edouard Manet and Camille Pissarro. Though more of an established artist, Courbet had several works rejected for exhibition. If the Academy didn’t understand the strength of Courbet’s independent spirit, they certainly found out. Rather than sit and complain, Courbet decided that if they would not exhibit all the work he submitted, he would have to do it himself. Next to the fair’s arts pavilion on the Avenue Montaigne, Courbet set up his own independent exhibition, which he called the Pavillon du Réalisme.

This is where Courbet had a great influence on later modernists like the Impressionists. Being among the first major artists to exhibit their work independently outside the organized Salon makes Courbet one of the most important forerunners of modern art. Many see his 1855 exhibition as an inspiration for later independent exhibitions like the 1863 Salon des Refusés, Edouard Manet’s pavilion at the 1867 World’s Fair, and, of course, the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874.

The most prominent of Courbet’s paintings at the Pavillon du Réalisme in 1855 was The Painter’s Studio. Like his other important works from the 1840s and 1850s, the canvas was enormous, measuring nearly twelve feet by twenty feet. However, it stands out among the rest of his work because it is what Courbet called a “real allegory”. Obviously, in strict Realism, allegory cannot exist. So, this is more of a statement about the artist himself. The work shows Courbet in the center, painting a landscape of the River Loue, which runs through his hometown of Ornans. Meanwhile, looking over his shoulder is a nude woman. Some have identified her as the muse of Realism inspiring Courbet to action. Others have claimed she represents traditional academic painting, to which Courbet has turned his back. On the other side is a small child wearing a torn shirt and wooden clogs. However, this poor boy is not looking at the canvas; he’s looking at the artist. He is quite literally looking up to Courbet, representing the future of art.

On the right side of the canvas are depictions of Courbet’s colleagues. We see artists, intellectuals, and patrons like Charles Baudelaire and Alfred Bruyas. Meanwhile, the opposite side contains what Courbet described as “the other world of ordinary life”. While some have interpreted that description as examples of different people you would find in society, others have found many references to the various types of painting. The poor boy looking up at the artist and the beggar woman on the floor breast-feeding her child are representative of genre painting. Meanwhile, the semi-nude figure peeking out behind the canvas is an artist’s mannequin propped up to serve as a reference for a crucifixion painting, representing religious art. It’s almost hidden, both in darkness and behind Courbet’s canvas, representing Courbet’s rejection not only of religious art but the importance placed on religious art by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. At the mannequin’s feet, there is a skull, which was often found in crucifixion paintings to represent death. However, the skull and a collection of other objects, including a guitar, a knife, and a feathered hat, are reminiscent of Golden Age Dutch still-life paintings, of which there were likely many in the Louvre. Lastly, the most prominent figure on the left-hand side is a portrait of the Emperor Napoleon III. It likely shocked audiences at the time since he wears a thick overcoat and thigh-high hunting boots, the attire of a provincial hunter or, more specifically, a poacher. This is where Courbet’s politics spills out onto the canvas. It is clearly a criticism of Napoleon III. Republicans and revolutionaries in France who supported the Revolution of 1848 viewed Napoleon III as having hijacked the revolution to transform the country into a monarchy. He is a poacher, hunting on lands that do not rightfully belong to him.

Upon seeing The Painter’s Studio, Eugène Delacroix, the leading Romantic painter at the time, remarked that the Academy jury “rejected one of the most remarkable works of our time, but Courbet is not the man to be discouraged by a little thing like that.”

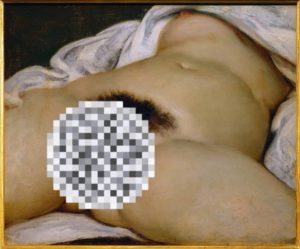

#4 – Courbet the Agitator: L’Origine du monde

As the 1850s became the 1860s, Courbet began to distance himself from the peasant scenes that had brought him fame and infamy. Soon, he painted landscapes, floral still-lifes, portraits, and female nudes. Some saw these later works as Courbet displaying the variety of his subjects. Others saw his departure from his monumental Realist paintings as a sign of decline, that it was all downhill after The Painter’s Studio. In 1866, however, Courbet showed everyone that he was not above controversy when he debuted L’Origine du monde. It was a bold departure from prevailing artistic norms, particularly in its explicit depiction of female nudity. He had done this previously with his 1853 painting The Bathers, which gives us an unromanticized portrayal of female nudity devoid of any historical or mythological context. L’Origine du monde directly confronted nineteenth-century social taboos surrounding nudity and sexuality, challenging traditional representations of the female body in art. To Courbet, it was simply a continuation of Realism, seeking to portray subjects as objectively as possible. L’Origine du monde does not present the female body as imagined and painted by generations of past artists. At the time of its creation and even today, it sparks debate about sexuality, censorship, and the nature of art. Just last month, protestors at the Centre Pompidou-Metz used L’Origine du monde not just to criticize the sexism still present in the art world but to call out some art world figures as predators, most notably the curator Bernard Marcadé, who co-organized the Pompidou exhibition L’Origine du monde was a part of.

Its enduring relevance underscores the power of art to challenge social norms and provoke critical reflection. L’Origine du monde is significant for its artistic merit as well as its role in challenging conventions and sparking dialogue about sexuality, censorship, representation, the male gaze in art, and even the nature of art itself.

#5 – Courbet in Exile: The Trout

For a political radical, it’s somewhat ironic that Courbet’s career almost entirely coincided with the Second French Empire. He first came to prominence not long after the 1848 Revolution and the empire’s founding a few years later. In addition, his career suffered greatly during the empire’s collapse. Prussia claimed victory in the Franco-Prussian War in May 1871, leading to Napoleon III’s fall from power. After the end of the war, a new republic rose from the empire’s ruins. New elections brought a conservative government to power. Fearing the radical politics of the Parisian lower and working classes, they moved the government seat to (of all places) Versailles.

With the new government seemingly abandoning the city, groups of liberal republicans, socialists, and proto-anarchists formed the Paris Commune, operating independently of the national government. The Commune governed the city using mutual aid networks created during the Prussian siege of Paris months earlier. Courbet was a republican influenced by the prominent socialist figures of his day like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. While the Commune governed the city, Courbet brought together the artists of Paris to decide cultural matters as a union. Their biggest task was organizing that year’s Salon, this time with far looser and more liberal rules about who could exhibit works of art and how to judge them. However, one act sealed Courbet’s fate in the eyes of conservatives. During the war, before the Commune’s establishment, Courbet proposed that the government relocate the column at the center of the Place Vendôme to a different part of Paris. The column commemorates French victories during the First Empire. A statue of Napoleon I sits at the monument’s peak. Courbet wrote that the monument is “devoid of all artistic value” and expresses “the ideas of war and conquest” unbefitting of a republic. However, the Commune’s executive committee took it further and toppled the column. A photograph of Communards posing next to the toppled column shows Courbet among them (ninth from the left). After ten weeks, the French army marched into the city and brutally crushed the Commune. Courbet was arrested and sentenced to six months in prison because he was blamed for the Vendôme Column’s destruction.

After Courbet’s release, his rheumatism and alcoholism worsened. The government ordered him to personally pay for the Vendôme Column’s reconstruction, which amounted to 323,000 francs (or approximately $7.3 million in 2024). Unwilling to pay these reparations, Courbet went into a self-imposed exile in Switzerland in 1873. He would only live a few more years, but he created several important paintings in that time. His series of twenty-one landscapes capturing the Château de Chillon on Lake Geneva are well-known, yet I’ve chosen his Trout paintings to represent his life in exile. Courbet began his Trout series while still in Paris but continued while in his Swiss exile. In all three paintings, he captures the fish hooked on the line, with their mouths and eyes open, gills bloody. The fish are caught and dying but still alive. Some have theorized that, like The Painter’s Studio, the Trout paintings have a fair amount of allegory, possibly serving as a symbolic self-portrait: beaten, bloodied, and dying, but not quite dead yet. The art critic Robert Hughes described Courbet’s Trout paintings as having “more death in it than Rubens could get in a whole Crucifixion”. Courbet would pass away in 1877 from complications brought on by his drinking. It would be over forty years before his remains were brought back to his hometown of Ornans, where he was buried in 1919.

Gustave Courbet sought to capture all observable humanity, particularly the dirty, ugly, and painful aspects. In his History of Modern Art, H.H. Arnason described Courbet as representing “the three-way conflict of past, present, and future more clearly than any other artist of his time.” His choice of subjects and his creative independence would pave the way for later modernists, laying down part of the bedrock of twentieth-century and contemporary art. He was, in more than one way, a revolutionary. His effect on art can probably be best summed up by the French writer Emile Zola, who wrote in 1868 that after Courbet, “no-one would now dare to say that the present day is unworthy of being painted”. In the past, artists used paint, marble, and bronze to show us what we once were. But it was Courbet and the Realists who decided to use their art to show us who we are and what we can be.