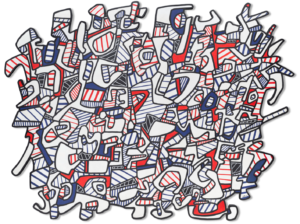

Lice tapissé by Jean Dubuffet

On Thursday, June 6th, Christie’s Paris hosted a small sale featuring a collection of twentieth-century artworks owned by the French auto manufacturer Renault. The company began building its collection in 1967, reaching out to artists to buy and commission pieces for the benefit of their employees. This collection includes significant works by renowned artists such as Roberto Matta, Jean Dubuffet, Joan Miró, and Robert Rauschenberg. These artists were all persuaded to include their work in the Renault collection because of the company’s policy that it would preserve the collection indefinitely; that once it was part of the collection, the company would not sell it. Rather, it would be displayed at Renault offices for the benefit of the employees, not to mention the general public, when the company would loan some of these pieces to museums for exhibitions.

Renault stopped buying art for the collection in 1986. Despite the initial promise to keep everything together in the company collection, Renault consigned sixty-two works to Christie’s out of the 550 total pieces. According to the company, the proceeds from the sale will go towards a new cultural endowment; allowing them to buy works from contemporary artists, focusing on street art. This plan has received serious opposition.

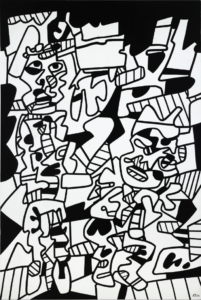

Paysage avec villa et personnage by Jean Dubuffet

On May 28th, the French newspaper Le Monde published a letter from the estates of several artists, expressing that they “categorically oppose the dispersal of a significant part of this collection”. They argue that by acting in violation of the conditions under which the artists initially agreed to contribute works to the collection, the company is, in their view, “completely betraying its commitment to artists”. In addition, Delphine Renard, daughter of the collection’s originator, Renault senior executive Claude Renard, spoke to the newspaper Le Figaro, saying that the sale “distorts and disfigures a unique ensemble”. This personal perspective from the artists and their families adds a human element to the issue, making it more than just a business decision.

The group of works were actually offered in two sales – one on Thursday and the other on Friday. The Thursday sale offered thirty-two lots by various artists, mostly European but also American and Venezuelan. It was a resounding success, with twenty-two lots (69%) selling over their estimates. Seven of these lots sold for more than double their high estimate, including EOS XII, an example of sculpture cinétique, or kinetic sculpture, by the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely (est. €50K to €70K; hammer €320K). All three top lots were works by the French artist Jean Dubuffet. In fact, half of the top ten lots featured in the sale were paintings by Dubuffet, mainly created in the early 1970s. Two of the three top lots consisted of vinyl paint on canvas, while the number one lot, Lice tapissé, was made with acrylic paint on an irregularly shaped piece of Klegecell, a PVC-based foam. Lice tapissé just squeaked by to sell within its €1 million to €1.5 million estimate range, with the hammer coming down at €1.1 million / $1.19 million (or €1.37 million / $1.49 million w/p). The other two Dubuffet paintings, Paysage avec villa et personnage (est. €700K to €900K) and Le Moment critique (est. €600K to €800K), surpassed their high estimates, selling for €1.04 million and €850K, respectively. Because of the number of lots that not only sold over estimate but exponentially so, the thirty-two lots brought in €8.35 million / $9.1 million (or €10.48 million / $11.4 million w/p) against a pre-sale maximum estimate of €6.37 million.

Le Moment critique by Jean Dubuffet

The Friday auction consisted entirely of works on paper by the Belgian-French artist Henri Michaux. Half of this sale sold below estimate, while the most valuable lot, an untitled 1981 ink drawing, went for €8K / $10.2K (or €10.1K / $12.8K w/p). Though the Michaux works had a 100% sell-through rate, Christie’s fell a mere €200 short of hitting the sale’s €131K minimum estimate. It served almost like an afterthought compared with the sale the previous day.

The sale has raised serious ethical concerns. As the collection’s owner, Renault has the right to decide the fate of the artworks. However, the sale seems to contradict with the original intent behind the collection’s inception. In the past, museums and art foundations have been prevented from liquidating any of the works they own if such a sale runs contrary to the intent or mission of the institution. The case of Renault, being a private, corporate collection, presents new, complex ethical (and possibly legal) territory, leaving some to question the boundaries of art ownership.

Christie’s Controversy Over Renault Auction

Lice tapissé by Jean Dubuffet

On Thursday, June 6th, Christie’s Paris hosted a small sale featuring a collection of twentieth-century artworks owned by the French auto manufacturer Renault. The company began building its collection in 1967, reaching out to artists to buy and commission pieces for the benefit of their employees. This collection includes significant works by renowned artists such as Roberto Matta, Jean Dubuffet, Joan Miró, and Robert Rauschenberg. These artists were all persuaded to include their work in the Renault collection because of the company’s policy that it would preserve the collection indefinitely; that once it was part of the collection, the company would not sell it. Rather, it would be displayed at Renault offices for the benefit of the employees, not to mention the general public, when the company would loan some of these pieces to museums for exhibitions.

Renault stopped buying art for the collection in 1986. Despite the initial promise to keep everything together in the company collection, Renault consigned sixty-two works to Christie’s out of the 550 total pieces. According to the company, the proceeds from the sale will go towards a new cultural endowment; allowing them to buy works from contemporary artists, focusing on street art. This plan has received serious opposition.

Paysage avec villa et personnage by Jean Dubuffet

On May 28th, the French newspaper Le Monde published a letter from the estates of several artists, expressing that they “categorically oppose the dispersal of a significant part of this collection”. They argue that by acting in violation of the conditions under which the artists initially agreed to contribute works to the collection, the company is, in their view, “completely betraying its commitment to artists”. In addition, Delphine Renard, daughter of the collection’s originator, Renault senior executive Claude Renard, spoke to the newspaper Le Figaro, saying that the sale “distorts and disfigures a unique ensemble”. This personal perspective from the artists and their families adds a human element to the issue, making it more than just a business decision.

The group of works were actually offered in two sales – one on Thursday and the other on Friday. The Thursday sale offered thirty-two lots by various artists, mostly European but also American and Venezuelan. It was a resounding success, with twenty-two lots (69%) selling over their estimates. Seven of these lots sold for more than double their high estimate, including EOS XII, an example of sculpture cinétique, or kinetic sculpture, by the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely (est. €50K to €70K; hammer €320K). All three top lots were works by the French artist Jean Dubuffet. In fact, half of the top ten lots featured in the sale were paintings by Dubuffet, mainly created in the early 1970s. Two of the three top lots consisted of vinyl paint on canvas, while the number one lot, Lice tapissé, was made with acrylic paint on an irregularly shaped piece of Klegecell, a PVC-based foam. Lice tapissé just squeaked by to sell within its €1 million to €1.5 million estimate range, with the hammer coming down at €1.1 million / $1.19 million (or €1.37 million / $1.49 million w/p). The other two Dubuffet paintings, Paysage avec villa et personnage (est. €700K to €900K) and Le Moment critique (est. €600K to €800K), surpassed their high estimates, selling for €1.04 million and €850K, respectively. Because of the number of lots that not only sold over estimate but exponentially so, the thirty-two lots brought in €8.35 million / $9.1 million (or €10.48 million / $11.4 million w/p) against a pre-sale maximum estimate of €6.37 million.

Le Moment critique by Jean Dubuffet

The Friday auction consisted entirely of works on paper by the Belgian-French artist Henri Michaux. Half of this sale sold below estimate, while the most valuable lot, an untitled 1981 ink drawing, went for €8K / $10.2K (or €10.1K / $12.8K w/p). Though the Michaux works had a 100% sell-through rate, Christie’s fell a mere €200 short of hitting the sale’s €131K minimum estimate. It served almost like an afterthought compared with the sale the previous day.

The sale has raised serious ethical concerns. As the collection’s owner, Renault has the right to decide the fate of the artworks. However, the sale seems to contradict with the original intent behind the collection’s inception. In the past, museums and art foundations have been prevented from liquidating any of the works they own if such a sale runs contrary to the intent or mission of the institution. The case of Renault, being a private, corporate collection, presents new, complex ethical (and possibly legal) territory, leaving some to question the boundaries of art ownership.