When the painter Gustave Caillebotte died in 1894, he bequeathed his entire art collection to the French state. In his will, Caillebotte expressed his wish that the seventy-three paintings be displayed at the Musée du Luxembourg before being transferred across the Seine to the Louvre. This provoked a furious outburst from the Académie des Beaux-Arts, with the academic master painter Jean-Léon Gérôme leading the charge against this collection of Impressionist works from being accepted by the state. When he heard that Monet and Pissarro paintings could grace the Louvre’s walls one day, he remarked, “For the state to accept such filth would be a blot on morality.”

As the executor of Caillebotte’s estate, Pierre-Auguste Renoir reached a compromise after three years of negotiations with government officials. The paintings considered the least objectionable, amounting to thirty-nine works, would be kept at the Luxembourg until curators could make space at the Louvre. When Paul Cézanne heard that two of his paintings were among those selected, he is said to have exclaimed, “Now Bouguereau can go to hell!” This was unimaginable just twenty-five years before. Impressionism went from outsider art to being displayed at France’s national museums. Caillebotte’s collection was promised a spot in the Louvre (where it was eventually transferred in 1927), marking the end of an uphill battle that Impressionist artists had fought for decades. And today marks one hundred fifty years since that battle first truly began.

2024 is the one-hundred-fiftieth year of Impressionism. Of course, Impressionism didn’t just emerge from Claude Monet’s skull fully formed. Impressionism developed among European painters after generations of innovations in technique and technology, changes in abstraction and appropriate subject matter, as well as the popularization of painting en plein air. I’ve previously written about what helped the Impressionists achieve their vision, including British landscapes, French neoclassical and Romantic painters, and the invention of collapsible paint tubes. Therefore, there isn’t a single day art historians point to and say, “This is the start of Impressionism.” However, certain dates were important in its development as an artistic style. One of those dates was April 15, 1874. This was when the First Impressionist Exhibition opened in Paris.

This exhibition was the first major challenge against the supremacy of the Salon. For centuries, the Salon was the place to have your work exhibited and judged. The Salon’s judges, members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, therefore became the arbiters of artistic taste in Europe and North America. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Salon’s status and reputation faced opposition from some artists. These nonconformists asserted that artistic taste is inherently subjective. Therefore, it hurts creative innovation to have a centralized organization of tastemakers unilaterally determining what is and is not good art. Many of these artists previously had their work rejected for exhibition by the Salon. Had the Salon judges been kinder, we may not have gotten what came next. Last year, I delved into how artists’ repeated objections led to the Salon des Refusés, an exhibition for those works rejected by the Salon. This was the first crack in the Salon’s status as the sole authority over artistic taste. At the time, some recognized these cracks forming, deciding that independent exhibitions would be the thing to tear down the Salon’s complete authority. Paul Cézanne’s friend Antoine-Fortuné Marion once remarked, “All we must do now is exhibit by ourselves and we will pose a deadly threat to those old, one-eyed idiots.”

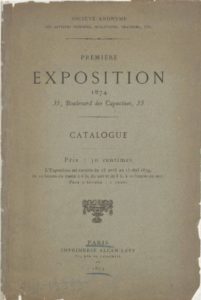

To help support one another, some of these nonconformists got together to create their own organization that would act somewhat like a joint stock company and a mutual aid society. On December 27, 1873, they founded the Société anonyme coopérative des artistes peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs. Its members would pay dues to the organization set at 60 francs per year. Its founding members included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, and many others. However, there were some debates over who should be granted membership. Paul Cézanne became the subject of one such discussion. He was viewed as an outsider since he was the only prominent artist among them from the far south of France. Most founding members of the organization were Paris natives or from small towns just outside the capital. Edouard Manet probably had the greatest dislike for Cézanne, thinking of him as an uncouth southerner. Even though Manet declined membership in the organization, he was still consulted as to whether they should grant Cézanne membership. Camille Pissarro was the only artist of note to advocate for Cézanne’s inclusion. On the other hand, Degas suggested that they bring in established artists like Eugène Boudin, Félix Bracquemond, and Auguste Ottin to exhibit with them to bolster the group’s legitimacy. The group’s members approved of this idea but thought inviting outsiders would be inappropriate if they excluded one of their own. Cézanne was, therefore, allowed to join.

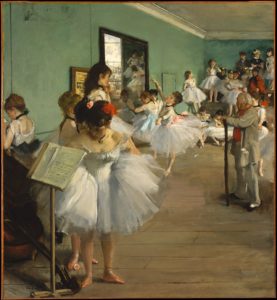

In 1874, the Salon would open on April 25th. To avoid it from overshadowing their show, they decided to open over a week earlier. The famous photographer Nadar allowed the group to use his old studio as their exhibition space at 35 Rue des Capucines, just a five-minute walk from the Madeleine Church. And so, on April 15, 1874, the First Exhibition, as they called it, opened to the public. On the walls were paintings like Edgar Degas’s The Dancing Class, the first of his ballerina paintings, as well as Impresion, soleil levant by Claude Monet. There were also seven works by Renoir, six by Sisley, ten by Morisot, six by Boudin, three by Cézanne, five by Pissarro, and three by Lépine. Close to two hundred visitors came on the first day. It was very small compared to the thousands the Salon would get, but it’s not nothing.

To distinguish themselves from the Salon, the exhibitors created a more egalitarian environment in how they arranged and displayed their work. The Salon exhibitions were often held at some of Paris’s most spacious venues to accommodate as many works as possible. Between 1857 and 1897, that space was the Palais des Champs-Élysées, also known as the Palais de l’Industrie (which was demolished to make way for the Grand Palais and Petit Palais). The walls were often incredibly large, so they hung the paintings to fill an entire wallspace. The Academy judges frequently used this as a form of ranking. The works approved for exhibition but still deemed inferior to the others were placed higher up and, therefore, more difficult to see. However, Pierre-Auguste Renoir was responsible for arranging and hanging the works for the First Exhibition. He chose to display all the paintings and prints in no more than two rows, making it incredibly easy for viewers to study each work individually.

The reviews were not kind, yet it was these negative reviews that the exhibitors were collectively given their name: the Impressionists. The term “Impressionism” was originally an insult meant to deride the group, first found in the writings of journalist and art critic Louis Leroy. He wrote a review of the exhibition for the satirical newspaper Le Charivari on April 25th. Leroy took the term “Impressionism” from Monet’s painting Impression, soleil levant. Monet himself used the term “Impression” in the title to deflect criticism that the painting seemed incomplete. About Impression, soleil levant, Leroy wrote, “A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is better than this seascape!” Leroy had little better to write about the other paintings. In viewing Pissarro’s Hoarfrost, he described how his friend who attended with him “thought that the lenses of his spectacles were dirty. He wiped them carefully and replaced them on his nose.” He later lamented, “Oh, Corot, Corot, what crimes are committed in your name!” Another journalist, Jules Claretie, declared that the exhibitors had “declared war on beauty”. However, while “Impressionism” was initially used as an insult, the artists soon adopted the name for themselves.

The exhibition lasted for a month, attracting a few thousand visitors. In the aftermath, one of the few critics sympathetic to the Impressionists was Jules-Antoine Castagnary. He saw the use of the term “Impressionism” among his colleagues and thought it was a rather appropriate descriptor. He wrote in the newspaper Le Siècle, “They are impressionists in the sense that they render not a landscape but the sensation produced by a landscape.”

While some of the artists sold nothing at all, there was a spark of hope when Monet sold five paintings, including Impression, soleil levant, to the department store owner Ernest Hoschedé. Even though Nadar had let the Impressionists use his space for free, they still had to pay for advertisement, printing the catalogues, and redesigning the rooms as an exhibition space. When the Société Anonyme convened in December 1874, they found that they owed a little over 3,700 francs, meaning each exhibitor would have to chip in and pay the organization 184 francs. After settling this matter, the members unanimously agreed to liquidate the Société Anonyme. But despite the show being a critical and commercial failure, the Impressionists had made a name for themselves. They had gathered just enough interest to survive and paint another day, staging another exhibition in 1876. The Impressionists would put on eight exhibitions in total between 1874 and 1886.

While Impressionism to some today seems as old-fashioned as its academic predecessors, it became the first movement of modern art in the Western world. It was not only in their technique and subject matter but in how they helped decentralize the art world. They paved the way for scores of smaller salons and exhibitions, helping jumpstart the careers of generations of modernists in the twentieth century. They also helped people realize that deviating from the norm is okay. Without the Impressionists and their struggle against the Salon’s institutional conservatism, the world would have never known the primitivism of Henri Rousseau or the bright colors of Mattise and Derain. We wouldn’t have gotten Seurat’s little dots, Pollock’s splatters, Dada, absurdism, or surrealism. Regarding today’s art world, we may not have gotten installations, performance pieces, minimalism, pop art, hyperrealism, or the advent of street art and graffiti. Impressionism may be conservative by today’s standards, but that doesn’t mean we should disregard it. It was the jumping-off point from which all modern art began.