I took an elective class for my arts requirement when I was at school. It was called Laughter and the Fine Arts and looked into humor and comedy in everything from Aristophanes to Modern Family. People have been making humorous art for millennia, but I feel like when thinking of this, we don’t often consider the modern masters of the last two centuries. Everything for them was very serious, yet they were all as human as anyone and could be silly, playing practical jokes and inserting laughter into their work.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment

Michelangelo Buonarotti’s work in the Sistine Chapel was incredibly long and arduous. It took the artist four years to complete the ceiling, plus another five years to create the fresco, The Last Judgment, behind the altar. Michelangelo brought the nude human form, the idealized figures of classical sculpture and statuary, into the heart of Western Christianity, which didn’t sit well with everyone. One of the most well-known stories about the Last Judgment‘s creation was when Pope Paul III entered the chapel to view Michelangelo’s progress. This was when the pope’s master of ceremonies, Biagio Martinelli da Cesena, expressed his objections to the amount of nudity in the scene. According to Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Biagio said that “it was a very disgraceful thing to have made in so honorable a place all those nude figures showing their nakedness so shamelessly, and that it was a work not for the chapel of a pope, but for a bagnio [bathhouse] or tavern.” In response to these criticisms, Michelangelo did make one noticeable change. In the bottom right corner of the enormous fresco, we see damned souls being ushered to Hell. Among them is Minos, the judge of the underworld, surrounded by a horde of demons. As his revenge, Michelangelo gave Minos his critic’s likeness. Additionally, he gave him donkey ears while a serpent bites at his genitalia. According to the chronicler Ludovico Domenichi, when Biagio saw this and complained, Pope Paul told him that there was nothing he could do about it since he was responsible for guiding souls to heaven and, therefore, could not do anything about what happens in Hell.

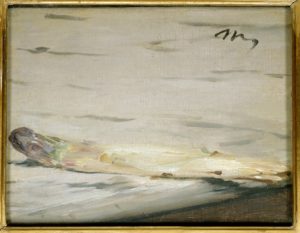

Manet’s Asparagus

Édouard Manet is considered one of the greatest European artists of the nineteenth century for having carved out his own variety of modernism between the Paris Salon and the nascent Impressionist movement. Because of the importance of his work, we often look at it through a rather strict academic lens. However, in some of his paintings, we see touches of lighthearted humanity. This is most apparent in a pair of paintings commissioned by the critic and collector Charles Ephrussi. In 1880, Ephrussi promised Manet 800 francs for a still-life of asparagus. Manet delivered on his commission, giving us Une botte d’asperge, a good-sized look at a bundle of white asparagus with purple tips laying upon a bed of greenery, much like a Paris grocer might display his inventory at the time. Research on the canvas has since revealed that Manet created the work painting wet on wet, meaning that he likely created the whole painting in a single sitting. Ephrussi enjoyed the painting so much that he paid Manet 1,000 francs. Manet was known for being an affable, witty personality in the Paris art scene, so he took the opportunity to make a little joke. Having been paid more than what he was commissioned, Manet went to work and created a separate, smaller asparagus still-life painting. While the original bundle measured 18 by 21 ½ inches, the smaller canvas was only 6 ½ by 8 ½ inches, showing a single stalk of asparagus on a tabletop. When he sent it to Ephrussi, he attached a note reading, “There was one missing from your bundle.” Unfortunately, viewing the two paintings side-by-side isn’t possible right now. While the single stalk is kept at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the original bundle now hangs at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne.

Brueghel’s Flatterers

Art historians often differentiate Pieter Brueghel the Elder from the Younger by referring to him as the Peasant Brueghel since he gained fame in his own time through depictions of peasant life in the Low Countries. However, it’s not like Brueghel the Younger completely abstained from peasant themes. Some of his most interesting work involves representations of common sayings and proverbs, which sometimes can be confused for simple representations of peasant life. For example, there’s a young man with a knife and some bread, which is sometimes associated with the proverb “The man who cuts wood and meat with the same knife.” He also had his interpretation of the classic “blind leading the blind” allegory. Then, there’s a depiction of a drunk man being forced into a pigsty by the rest of the village, often associated with the popular saying, “The pig must go into the stall.” In translating contemporary morality onto the panel or the canvas, Brueghel the Younger often required a bit of humor, and nowhere is that more apparent than in the painting known as The Flatterers. It shows a large man with a bag of money, pouring the coins out onto the ground while a group of smaller men make their way up his backside. It has a touch of the surreal, but the meaning becomes a parent when you understand the popular proverb it invokes: “Because so much money creeps into my sack, the whole world climbs into my hole.” It’s a rebuke of what we would now call brownnosing. Brueghel even includes a man in a long, brown robe in his crowd of ass-kissers, like that of a Franciscan friar, showing that even the seemingly-lofty among us can fall victim to greed and other vices. Even though the work is meant to convey a serious moral lesson, viewers at the time and even today can’t help but chuckle. There’s a hint of silliness, which I think only enhances the work’s message.

Rothko’s Seagrams Murals

Now for a bit of dark humor… in more than one way, I suppose. In 1958, the Canadian beverage company Seagram was about to move into its new headquarters at 375 Park Avenue in New York. The structure, known as the Seagram Building, was designed primarily by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and is one of the finest examples of the international style of architecture. Seagrams wanted a restaurant in the building, with works by a prominent artist for the interior. They picked Mark Rothko for the job at the recommendation of Alfred H. Barr Jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art. Rothko was well-known then but was only starting to become successful. He was looking for an excuse to create a large series of works experimenting with a darker color palette.

The Seagrams commission would give Rothko that opportunity and a space where he would show them all. He was hesitant, however, because of his dislike of materialist consumption, of which the new Seagram Building and its fancy restaurant would be symbols. He was only meant to make seven large paintings but created thirty, from combinations of red and orange to black and burgundy. After over a year of work, Rothko began to grow tired of the commission, to the point that he felt he was actively creating something intentionally antithetical to the eventual exhibition space. In 1959, he admitted to journalist John Fischer, “I accepted this assignment as a challenge, with strictly malicious intentions. I hope to ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room […]. If the restaurant would refuse to put up my murals, that would be the ultimate compliment.” At least Rothko was able to find a bit of humor in what he was doing. It was almost like a practical joke on big-headed businessmen. However, in 1960, Rothko was invited to dine in the new restaurant, the Four Seasons. It seems that was a breaking point for him, and not long after, he chose to cancel the initial contract. Rothko reclaimed all 30 paintings in the series and returned the money given to him. He later complained to his studio assistant, “Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine”. The Seagram murals, as they came to be known, were locked up in storage. They have since been sold and scattered, with nine being shipped off to the Tate Gallery in 1969.

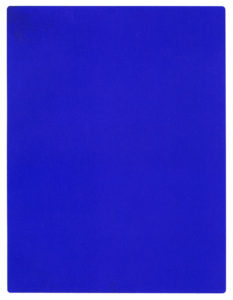

Yves Klein’s Blue Surprise

Yves Klein was a French artist in the immediate postwar period. He was foundational in what later became the nouveau réalisme school and was incredibly influential in developing minimalism, pop art, and performance art. However, many people who know his name will associate him not with a specific work but with a color. He developed International Klein Blue (IKB), a deep, dark shade of blue close to ultramarine, which he used extensively in his work. One of his most well-known paintings, IKB 191, is simply a monochrome painting consisting solely of a canvas painted with synthetic resin and then dusted with the paint’s dry pigment. However, there is a select group of people for whom the color is unforgettable because of an incident in April 1958. That month, Klein opened a new exhibition at the Galerie Iris Clert called Specialization of Sensibility from the State of Prime Matter to the State of Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility. This exhibition would later become known as the Void. The gallery’s windows were entirely painted with IKB, while a canopy of the same color was installed over the door. Twenty-five hundred people showed up to the opening. The gallery served the guests blue gin-and-Cointreau cocktails, which they drank before being let in about ten at a time. There, they saw the entire gallery completely cleared out and painted white. That’s it; nothing was on display or hanging from the walls. According to Klein, he had rendered all of his paintings immaterial, which in The Void could allow you to concentrate and get your mind to do all the creative heavy lifting. However, the show wasn’t over yet. When the gallery-goers returned home, they were in for a little surprise. The blue cocktails got their color from methylene blue, a saline solution used as a dye and a medication. Many guests urinated International Klein Blue for up to a week after the show. I’m not sure if it was intentional, but that’s what I call branding.