The Manhattan District Attorney’s office has been rather busy as of late. Several weeks ago, they confiscated an ancient Roman sculpture from the Cleveland Museum of Art believed to have been looted from an archaeological site in Turkey. And now, investigators have seized several works from out-of-state museums by the Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele that the Nazis stole from their original owner.

The three works were once in the collection of Fritz Grünbaum, an Austrian Jewish actor, singer, and songwriter who gained popularity performing in cabarets and theaters across Austria and Germany. Not long after Nazi Germany annexed Austria, Grünbaum attempted to flee to Czechoslovakia but was detained and sent to Dachau concentration camp. He was forced to sign over power of attorney, allowing the state to confiscate his art collection. He died at Dachau in 1941. Over the decades, the contents of his collection became dispersed throughout the world. In the last ten years or so, new research has uncovered the true provenance of some works. Furthermore, Grünbaum’s heirs have successfully made their case through the legal system. In 2019, the New York County Supreme Court ruled in their favor against the London art dealer Richard Nagy, stating that Grünbaum had signed over power of attorney under duress and was therefore invalid. This means that any work from his collection is still considered stolen, regardless of whether those possessing his works legally obtained them.

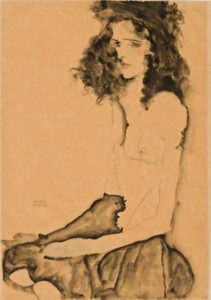

The Manhattan DA’s office confiscated works from three out-of-state cultural institutions: the Art Institute of Chicago, the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, Ohio, and the Carnegie Museums in Pittsburgh. The works confiscated were two watercolor and pencil works on paper entitled Russian War Prisoner (1916, valued at around $1.25 million) and Girl with Black Hair (1911, valued at $1.5 million), as well as a pencil drawing on paper called Portrait of a Man (1917, valued at around $1 million). The Carnegie Museums released a statement expressing that they are fully cooperating and are “acting in accordance with ethical, legal, and professional requirements and norms”. Oberlin College has not yet released a statement, but the Art Institute of Chicago certainly has. They seem less cooperative than the Carnegie Museums, coming across as a little resistant by claiming they are “confident in our legal acquisition and lawful possession of this work.”

The Manhattan DA’s confiscation adds complexity to currently ongoing civil cases. Grünbaum’s heirs are already suing these three institutions, as well as the Museum of Modern Art, the Morgan Library, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, to have around a dozen Schiele works returned. The fact that any district attorney’s office is getting involved means that what was once a civil matter may turn into a criminal case. It’s unlikely, but one never knows.