This is an update on the situation at the British Museum. Last month, it was revealed that Peter John Higgs, the museum’s former curator of Greco-Roman art, was fired after he was found to have stolen and/or damaged 1,500 to 2,000 items from museum storerooms over several years. The museum only uncovered Higgs’s hobby after an antiquities dealer found some of the works he stole on eBay. It’s unlikely he was doing it for the money since items worth tens of thousands of pounds were found online for sale with a £40 reserve. Since then, museum director Hartwig Fischer has stepped down several months ahead of his intended departure at the end of the year. He has since been replaced by a new interim director, Sir Mark Jones, who previously headed the National Museums Scotland and London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Jones previously worked at the British Museum, where, between 1974 and 1990, he served as assistant keeper of coins and medals.

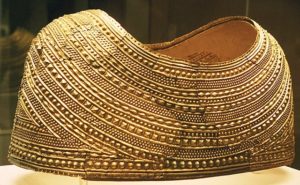

Since news of the Higgs theft broke, calls for repatriating stolen items kept at the British Museum have only intensified. Since the theft itself is a massive security breach, the incident has all but destroyed one of the last somewhat valid arguments in favor of keeping global cultural heritage in London, that being the British Museum’s reputation as an incredibly well-funded, secure, and prestigious place to house such a massive multicultural collection. With the British Museum losing its reputation as a secure repository for art and artifacts, the arguments for repatriation seem stronger than ever. Of course, Greece and Nigeria are some of the more well-known countries asking for their cultural heritage back. Bronze artworks looted from Benin City by British soldiers and marble sculptures taken from the Parthenon are some of the most famous stolen works infamously and defiantly kept in the British Museum’s collection. But with the news of the theft, several other countries are now asking for the return of their items. Chinese state media has called on the museum to return any items from its 23,000-piece Chinese collection acquired improperly or illegally. Ethiopia has renewed its efforts for the museum to return its Maqdala Collection, made up of Ethiopian artifacts looted by soldiers from Emperor Tewodros II’s palace during the British invasion of the country in 1868. There have even been repatriation requests from Wales, England’s next-door neighbor. Some Welsh politicians now demand the return of several items to their country of origin, including the Moro Hebog Shield and the Mold Gold Cape. Many of the British Museum’s Welsh items are not even on display and can be moved to a Welsh cultural institution such as the National Museum Wales in Cardiff. Repatriation does seem slightly more likely, especially with Jones’s previously supporting proposals for the Parthenon Marbles to be shared between the British Museum and Greece. Some members of Parliament have recently proposed changing or repealing the British Museum Act of 1963, which bars the museum from ‘disposing’ of any part of the museum’s collection. However, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has unequivocally opposed the Marbles’ return to Greece, so we’ll see how it goes.

Some analysts and commentators have pointed out, however, that the Higgs theft and the issue of repatriation are more interconnected than it may seem. One of the main reasons Higgs could pillage the museum storerooms for as long as he could was because the British Museum has only properly cataloged around half of its collection. Of the 4.5 million items held by the museum, only around 2 million have pages with photos and information publicly available on its online catalog. Therefore, it was all too easy for Higgs to steal and try to sell the artifacts he is accused of stealing since no one could easily trace them back to the museum storerooms. Some have speculated that this lack of proper cataloging was an intentional move by the museum administration to hinder future restitution claims. By restricting public knowledge of the specifics of the museum collection, future repatriation efforts would be much more difficult. Besides, you can’t give back what no one knows you have. Over the years, this created what Dan Hicks, curator of Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum, called “a disfunctional institutional culture” where the museum’s collection is treated “not as a public resource but a private archive” by its administration and the British government. To some, it seemed fairly obvious that something like this would come from such an antiquated museum curation style. It was only a matter of time before someone noticed the museum’s weaknesses and took advantage of them as Higgs did. The museum trustees may have thought that a lack of transparency would protect their reputation, yet all it has done is cause it to crumble into ash.