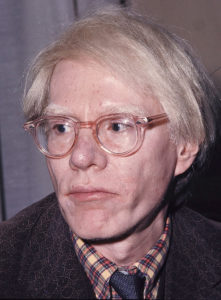

Andy Warhol is known for many things, soup cans and flowers among them. But his portraits are often cited as some of the pop art icon’s most recognizable works. From Marilyn Monroe to Mao Zedong to Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol seems to have immortalized every great cultural figure of the twentieth century in neon-colored silkscreen. Among Warhol’s portrait subjects, the musician and 1980s icon Prince is just one of many. But it’s a Warhol portrait of Prince that’s the subject of an upcoming US Supreme Court case.

It all started in 2016 following Prince’s death, when Vanity Fair published an article on the late musician. Accompanying the article was a number of colorful portraits of Prince done by Andy Warhol in the years leading up to the artist’s 1987 death. That’s when Lynn Goldsmith noticed something out of place. Warhol’s portraits bore a striking resemblance to a photo she had taken of Prince in 1981. Lynn Goldsmith is a musician and a photographer known for having taken photos of many celebrities and public figures. While she may occasionally snap a picture of Hillary Clinton or the Dalai Lama, she’s always been a musical photographer at heart. Singers and musicians are her most common subjects, including Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Michael Jackson, and Bruce Springsteen. She’s also taken pictures for a number of recognizable album covers, most iconically Frank Zappa’s Sheik Yerbouti. But the center of this legal battle has to do with Goldsmith’s 1981 black-and-white portrait of Prince.

Goldsmith originally licensed the photo to Vanity Fair in 1984 for use in an article about Prince entitled “Purple Fame”. The magazine then reached out to Warhol to create a portrait based on Goldsmith’s photograph. The Warhol portrait accompanied the article, but Vanity Fair credited Goldsmith for the original work. However, Warhol went on to create an additional fifteen portraits of Prince based on the original photograph without Goldsmith’s permission. After discovering this, Goldsmith reached out to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF), the organization that holds the copyright to all Warhol works. It seems her efforts to remedy the situation failed, because she then registered the original photo with the US Copyright Office. The AWF sued, while Goldsmith countersued, starting the legal battle that has continued to the present day.

In New York federal court, Judge John Koeltl ruled that although photographs are copyrightable, “the subject itself – and general features of that subject – are not.” Furthermore, Judge Koeltl wrote that Goldsmith doesn’t really have a case against the AWF because of Warhol’s transformation of the original photograph. The changes that Warhol made “result[ed] in an aesthetic and character different from the original. The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.” This decision, however, was overturned on appeal. The panel of appellate judges ruled that a secondary work being transformative cannot be determined just by the artist’s intent or the perceptions of the work. “[W]hether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic – or for that matter, a judge – draws from the work. Were it otherwise, the law may well ‘recogniz[e] any alteration as transformative.’” Faced with this new ruling, the AWF has appealed to the Supreme Court, who agreed to hear the case this past Monday.

A group of professors of both copyright and art law, as well as lawyers representing the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, and the Brooklyn Museum, have already submitted briefs to the Supreme Court supporting the AWF’s case against Goldsmith. While the AWF wants to portray the situation as artistic free expression under siege by some random photographer and the US legal system, what this case really deals with is simple: fair use within the context of copyright. These cases are context-based, and even if the justices side with Goldsmith, by no means will it create a new case law precedent for future free use copyright disputes. In law, there are certain circumstances where the free use justification is applicable, like commentary or journalism. No author is going to sue a literary critic because they used a quote from one of their books in a review. But taking someone else’s photograph, making an exact copy via screenprint, and then just changing the color is, by most people’s definition, not a wholly original work and is a clear and blatant infringement of copyright. The AWF is just making a fuss over a mistake their namesake made, and now they don’t want to look bad in front of everyone.