Julien Dupré

(1851 - 1910)

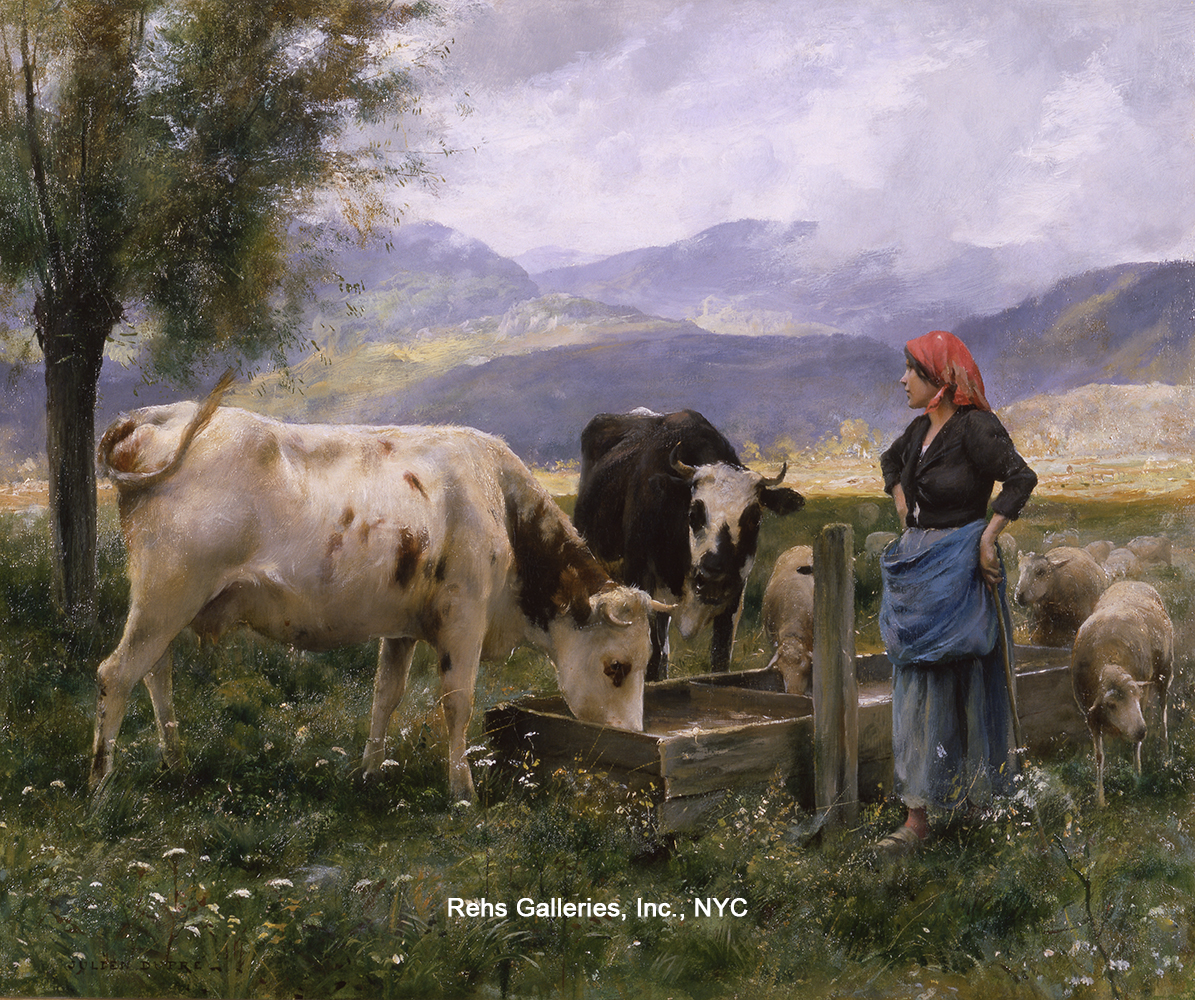

Une Prairie

Oil on canvas

18 1/4 x 21 3/4 inches

Framed dimensions:

28 x 31 1/2 inches

Signed

BIOGRAPHY - Julien Dupré (1851 - 1910)

Julien Dupré grew up in the Marais district of Paris, one of the oldest quarters of the city and one of the most diverse. Born on March 18, 1851, to Pauline Célinie Bouillié (1830-1885) and Jean-Marie-Pierre Dupré (1809-1904), he was baptized two days later in the parish church of Saint-Jean-Saint-François (today Sainte-Croix des Arméniens). His half-brother Jean was sixteen years old at the time, and the family would welcome their third child, Julie, in 1852. For many years, they lived at 11 rue des Enfants Rouges across the street from the site of the medieval Knights Templar complex.

During Dupré’s childhood, the Marais was primarily a working-class neighborhood, albeit one filled with historic buildings; the residential square of the Place des Vosges from the reign of Henri IV; the Hôtel Carnavalet, remodeled by François Mansart in the 1650s; and the Hôtel Soubise, the townhouse that ushered in the rococo style under Louis XV. [i] In contrast to these monuments of an aristocratic past, the Marais was home to a large Jewish community who had settled there in the aftermath of the French Revolution. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was a vibrant commercial district of working people, and it was in that milieu that Dupré’s father worked as a jeweler.

Making jewelry—both costume jewelry and fine jewelry—seems to have been a family business for several generations, and it would continue to be so in Julien Dupré’s time; his half-brother Jean and sister Julie would both train as jewelers, and Julie would also marry a jeweler. Undoubtedly, Julien was expected to become a jeweler, but his father apprenticed him to a lacemaker’s shop in the late 1860s, perhaps because of his aptitude for drawing. His time as an apprentice lacemaker, however, was short. The onset of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 forced the lacemaker’s shop to close, and Dupré became a soldier, completing his two-year tour of duty in 1873.

In 1872, before his military service had ended, Dupré enrolled in a sketching class at the École des arts décoratifs, where he studied with Monsieur Laporte to prepare for his application to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Once accepted, he entered the studio of Isidore Pils (1813-1875) and, after 1875, the studio of Henri Lehman (1814-1882), where he met Georges Laugée (1953-1937), who would become a lifelong friend. The post-war years were a heady time for young artists in Paris. The French defeat at the hands of the Prussians was a bitter outcome, particularly for Parisians, whose city had been badly damaged during the Commune of 1871. Political differences ran deep, a situation that was only aggravated by the presence of occupying Prussian troops in the city.

The art world was similarly fractured, particularly as the Realist generation of the 1850s and 1860s now had a strong influence and relatively secure position within the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Middle-of-the-road Realists were increasingly accepted within the academy although more avant-garde Realists such as Edouard Manet and Gustave Courbet were still perceived as pariahs. [ii] Into this context came a younger generation of artists who had begun their careers in the 1860s only to have them interrupted by the war. Some of them, such as Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet, traveled outside of France during the conflict, painting in Holland and ultimately crossing the Channel to England in the fall of 1870. Others stayed in Paris or moved to country homes as they could. By 1873, most of them had returned to Paris to begin planning an independent exhibition that had first been proposed in the closing years of the 1860s. On April 15, 1874, their exhibition opened at the studio of the photographer Nadar, attracting considerable press attention and no small amount of public curiosity. Undoubtedly, Dupré would have visited this exhibition, and in fact, his painting, Wooded Landscape with a Woman by a Haystack (1874), reveals his experimentation with some of the techniques of Impressionism.

Georges Laugée’s father, Désiré François Laugée (1823-1896), would also become an important influence on Dupré in the mid-1870s. Most likely, Dupré met the senior Laugée during a visit to the family’s country home in Nauroy near Saint-Quentin. Désiré Laugée was a respected academic painter of religious subjects, portraits and public murals. By the time that Dupré met him, he had also developed an interest in painting scenes of rural life.

Finally, it must be mentioned that there was a growing interest in depicting rural life among the emerging Naturalist painters. Naturalism is firmly grounded in the Realist painting of pre-war France, but artists such as Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884), Léon Lhermitte (1844-1925), P. A. J. Dagnan-Bouveret (1852-1929)—and Julien Dupré—began to develop a focused interest in the daily life of ordinary rural people. They were all born within four years of each other, and came to maturity in the shadow of the Franco-Prussian War. The work of Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) and Courbet were key influences as was the Impressionists’ fascination with light and open brushwork. What linked these artists was their emphasis on rural workers, whether agricultural laborers, miners or the small business people of country villages. What differentiated them from their more academic colleagues was their dedication to portraying the reality of country life unapologetically.

Dupré made his debut at the Salon on May 1, 1876 with two paintings: La Moisson, en Picardie (Harvest in Picardy) and Le repos des moissonneurs (Harvesters Resting). Two weeks later, on May 17, he married Marie Eléonore Françoise Laugée (1851-1937), the sister of his good friend, Georges. Marie had trained as a painter in her father’s studio and with the academic painter Evariste Vital Luminais (1821-1896) in Paris. She made her Salon debut with two drawings in 1874: Portrait de Mme. L and Etude. She would continue to paint throughout her life. The newlyweds lived with the Laugée family in the Passy neighborhood of Paris near the Bois de Boulogne.

After a promising debut at the Salon, Dupré focused his attention on establishing his career, submitting Faucheurs de siegle (Rye Reapers) to the Salon in 1877 and, in 1878 Lieurs des gerbes (Binding Sheaves), which was purchased by the state. In 1879, he exhibited two paintings; La récolte des joins (Hay Harvest) was sold to Goupil, and Glaneuses (Gleaners) was purchased by Knoedler, thus ensuring that young artist was already developing a steady market for his work. [iii] In addition, the Paris branch of the London-based gallery Arthur Tooth and Sons began to purchase works from Dupré, thus introducing his work to a British audience. One member of that international audience was a relatively obscure painter working in The Hague who described Dupre’s Salon entry for 1881— Au Pâturage (In the Pasture)— as “outstanding, very energetic and very true to life.” That artist was Vincent van Gogh. [v]

Early in their careers, Dupré and Georges Laugée set up a studio together at 14 boulevard Flandrin, not far from their homes. They would share this space for many years. It was here that Dupré began to accept students in 1882, perhaps because he had won a Second Class medal at the 1881 Salon, which meant that he no longer needed to submit his work to the juries for the annual exhibition. This freed up time to focus instead on educating the next generation of young artists—and providing a reliable income for his family. One of his first pupils was George W. Chambers (1857-1897) of St. Louis, Missouri; the American had previously studied with Jean-Léon Gérôme, but it was under Dupré’s tutelage that he began to exhibit at the Salon. [iv] Over the next few decades Dupré would continue to teach—both women and men—from across Europe and the United States.

At home, Dupré and Marie had two young children: Thérèse, who was born in 1877 and Jacques, who arrived in 1879. Five years later, the family moved to 10 boulevard Flandrin, just steps away from the studio, where they would have more room. A third child, Madeleine, was born there in 1885. All of Dupré’s children would learn to draw and paint, although only Thérèse would pursue it as an adult. Madeleine would become a pianist and Jacques a physician.

The years 1882-1883 marked a change in Dupré’s art. Two paintings that are almost identical reveal this evolution clearly. The earlier canvas, Au pâturage (In the Pasture) from 1882, depicts a young woman trying to restrain a cow by pulling on its halter. The cow, however, wants to trot down the hill where the rest of the herd is grazing. The 1883 painting of the same subject utilizes a similar composition, but with a slightly closer view of the interaction between cow and cowherd. There are minor differences in the background and the sky (one is cloudy, one is sunny) but what is most striking is Dupré’s shift from a relatively smooth, brushed canvas to a more freely painted surface where the use of a palette knife is evident. [vi] In the following decade, the artist would employ this expressive use of paint in many of his works.

Dupré’s Salon painting from 1883, Le Berger (The Shepherd), exhibits another emerging direction in his use of a large format canvas. By portraying rural workers on this scale, he positions them squarely in the company of traditional history paintings, a direct refutation of the academic prescription that such rustic scenes were suitable only for small scale genre paintings. The solitary figure of the shepherd stands with his back to the viewer, his ragged cloak visibly torn and mended; both he and the dog by his side seem quietly alert gazing over the flock of sheep in their charge. There is no narrative, just a mood of calm and an image that invites contemplation.

By the mid-1880s, Dupré’s career was well established and he was selling an average of nineteen paintings each year between 1886-1890. Most of those paintings were handled by Etienne Boussod, who was the son-in-law of the art dealer Adolphe Goupil. Dupré’s works would have been sold at Boussod’s contemporary art gallery in Montmartre, which was managed by Théo van Gogh from 1878 until his death in 1891. [vii] The gallery also handled Impressionist works by Claude Monet and Edgar Degas and eventually, post-Impressionist paintings.

The other gallery that handled a significant number of Dupré’s paintings was M. Knoedler & Co. of Paris and New York. Michel Knoedler originally worked for Goupil & Cie, and in 1852, he was sent to the US to manage their New York branch. Five years later, he purchased the New York gallery from Goupil, and established the Knoedler Gallery as a primary entry point for French art into the American market. [viii] One of Dupré’s earliest American sales was his 1886 Salon painting, Le Ballon (The Hot Air Balloon), which Knoedler handled for a New York City banker, George Seney. Within a year, Seney loaned this large canvas to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, making it the first Dupré painting to enter an American museum collection.

In the US, Blakeslee Gallery also became a frequent purchaser of Dupré’s paintings. In 1887, for example, six of his canvases were sold directly to Blakeslee. The typical buyer was a wealthy businessman—often from humble circumstances—who was assembling a small private collection, in part to establish his family’s cultural legitimacy as educated and sophisticated people. The American taste for French art during the Gilded Age illustrates the ease with which visual art can cross international boundaries, but also the occasional irony of the divergent interpretations of any given image.

The most well-known instance of this phenomena is Millet’s painting of The Gleaners, from 1857. Reproductions of this work were widely disseminated to schools, churches and undoubtedly many modest homes across the US; it was perennially popular well into the mid-twentieth century as an image of hard-working, noble and specifically Christian peasants. In France, this artwork was understood as a statement about the grueling nature of agricultural work and the desperate poverty of those laborers whose lives depended on their ability to gather up the remnants of grain left in the field after the harvest. The underlying political message is that the French government would be wise to recall that downtrodden workers had rebelled against unfair economic conditions in 1789 and 1848—and might well do so again if necessary. Dupré’s paintings may have been received in a similar fashion—as images of rural life in France without any particular social context. Because the US never engaged in the practice of gleaning as an obligation of the rich toward the poor, the French depictions of the practice carried very little political or social charge for American collectors.

The late 1880s and the 1890s found Dupré participating in a number of international expositions, beginning with the Paris International Exposition honoring the centennial of the French Revolution; he showed three paintings and received a Silver Medal for his work. In September 1890, he expanded his geographical scope by submitting Bei der Heuernte (Hay Harvest) to the Second International Exhibition in Munich, where he received a Gold Medal. By 1896, Dupré was exhibiting with the Art Association for Bohemia in Prague, where his painting In the Fields from 1895 was purchased by the state; it remains today in the Prague National Gallery. On the other side of the Atlantic, Dupré’s works were included in the Minneapolis Industrial Exposition from August to October in 1890; the Worlds Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893; the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of Fine Arts Exhibit in Omaha, Nebraska in 1898; and the Fifth Annual International at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1900.

At home in Paris, Dupré took an increasingly active role in professional art organizations, serving on the jury for the Société des Artistes Français in 1890, and exhibiting faithfully at the Salon every year. On January 23, 1892, he received the French state’s highest honor for an artist—becoming a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. In 1900, he became a member of the Central Committee at the Salon, a post he would hold until his death; and he served on the Jury d'Admissions et de Récompenses (Admissions and Awards Jury) from 1900-1910.

The year 1900 also saw the city of Paris again hosting a grand world fair, celebrating the turn of the century, but also a new direction in the arts. Art Nouveau developments had been evident for at least a decade, but it was at the Exposition universelle that its importance as an international movement was validated. Exhibitors from across Europe and the Americas came together to greet the twentieth century with new ideas, technologies and aesthetics. Dupré was well represented at the Exposition Universelle with four paintings: Vaches à l’ombre (Cows in the Shade); La Vallée de la Durdent (Durdent River Valley); Dans la plaine (On the Plains); and Un Chemin au Mesnil (A Road in Mesnil). Like many others, his approach to painting had continued to evolve in the 1890s, in his case into a more meditative mood with an emphasis on the interplay of light and color. His subject matter remained the same, but his figures were now smaller in scale and often solitary.

In the first decade of the new century, Dupré and his wife Marie traveled to locations beyond their familiar territory of Picardy and Normandy. Although the exact purpose of the trip isn’t known, they spent the spring and summer of 1903 in England. Marie painted several canvases of an English country house, suggesting perhaps that they were visiting friends there. In 1908, Dupré purchased a plot of land in the mountain town of Mont-Dore in central France, where thermal springs had attracted visitors since ancient Roman times. In fact, the bathhouse had been rebuilt in the early 1890s in order to revitalize interest in the area. It is possible that Dupré was seeking the health benefits of the waters himself as his final illness was beginning to appear. Although there is no documentation of the exact nature of his condition, it is most likely that it was cancer. Dupré exhibited his last two paintings at the Salon in May 1909; L’été (Summer) and Dans la vallée (In the Valley). He died the following spring on April 16, 1910. Almost exactly a month later, the Salon staged a small posthumous exhibition of his last two paintings, Dans la campagne (In the Country) and Une bergère (A Shepherdess).

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Appleton Museum of Art, Ocala, Florida

Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine

Chimei Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati

Columbia Museum of Art, Columbia, South Carolina

Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, Tennessee

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Huntington Museum of Art, Huntington, West Virginia

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska

Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Narbonne, France

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Musée de Grenoble, Grenoble, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Carcassonne, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dunkerque, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, France

Musée St. Denis, Reims, France

Musées de Cognac, Cognac, France

Musées Ville LeMans, LeMans, France

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, France

Prague National Gallery, Prague

Reading Public Museum, Reading, Pennsylvania

San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego

St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis

University of Kentucky Museum of Art, Lexington, Kentucky

[i] The Hôtel Carnavalet today is home to the Musée Carnavalet, which contains collections related to the history of Paris. The Hôtel Soubise now houses the Musée des Archives Nationales.

[ii] Gustave Courbet went into exile in Switzerland in 1873 after completing his prison sentence at Saint-Pelagie, but failing to provide enough money to pay for the reconstruction of the Vendôme Column, which has been dismantled at his suggestion during the Commune. Regardless of his absence from Paris, Courbet’s influence was considerable among the younger generation of artists.

[iii] Dupré began keeping an account book in 1876 and maintained it consistently throughout his life. Julien Dupré, Account Book entries for 1876, 1877, 1878 and 1887. Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York.

[iv] George W. Chambers returned to the US in 1885 to accept a position at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts. Shortly thereafter he moved to Nashville, Tennessee to work at the newly founded Watkins Institute; he joined the faculty of the Nashville School of Art in the 1890s, but died in 1897 at age thirty-nine.

[v] Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Théo van Gogh, [No. 292], The Hague, December 10 1882.Van Gogh Museum inv. #b264 V/1962.

[vi] The 1882 version of Au pâturage (In the Pasture) belongs to the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University of St. Louis. See https://www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/collection/explore/artwork/1834.

The 1883 version belongs to the University of Kentucky Art Museum, Lexington, KY. See https://finearts.uky.edu/art-museum/exhibitions/one-one.

[vii] The name of the gallery was changed several times between 1875 and its closing in 1919. In 1875, it was Galerie Goupil and three years later, it had become Galerie Goupil/Bousod et Valadon & Cie. The Goupil name was dropped in 1900. For a brief explanation, see the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC website at: https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.8418.html. For detailed research in the Goupil/Boussod and Valadon stock books, see the Getty Research Institute at: https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/digital_collections/goupil_cie/books.html

[viii] The Knoedler archives are held by the Getty Research Institute. See https://www.getty.edu/research/special_collections/notable/knoedler.html