Joseph Caraud

(1821 - 1905)

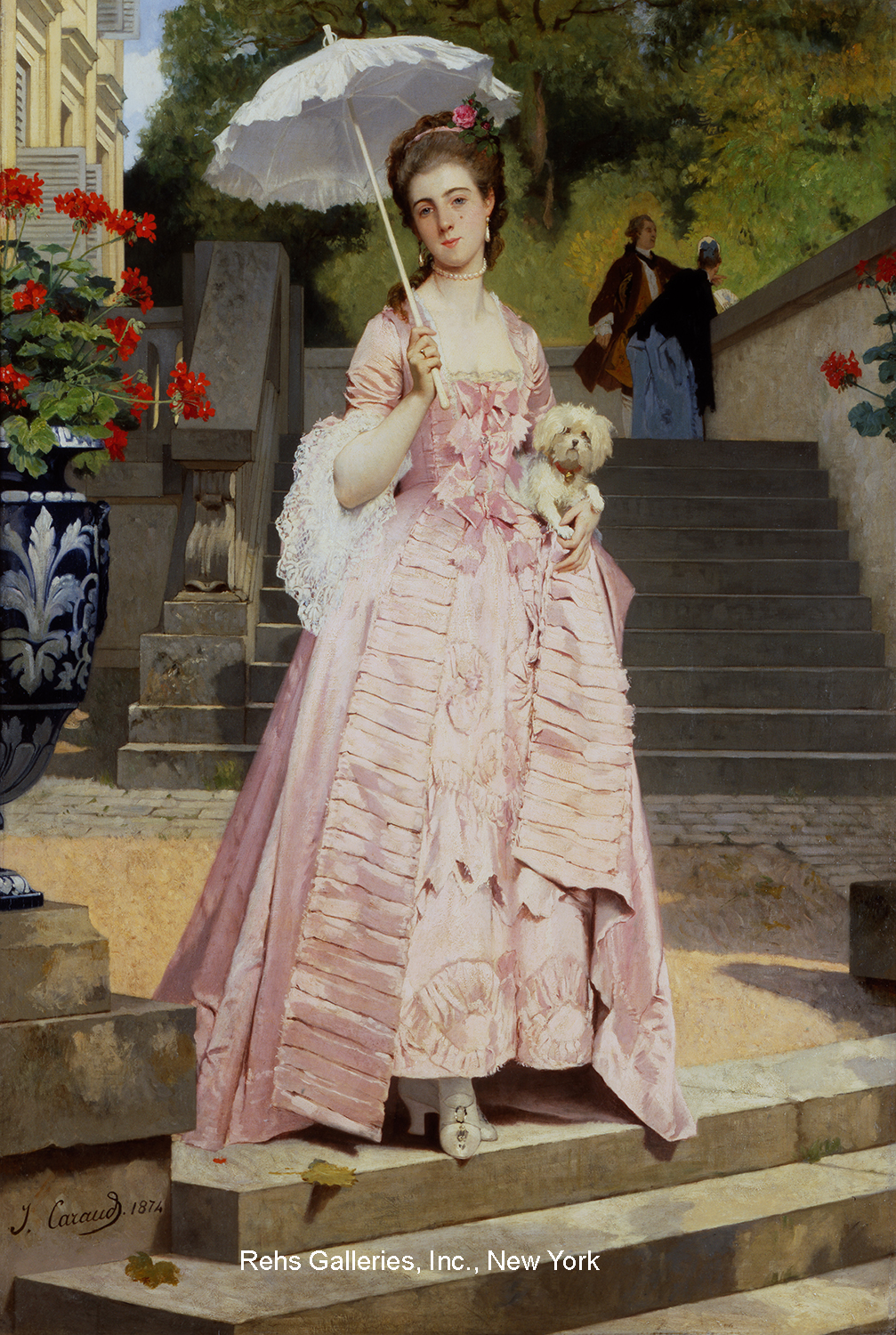

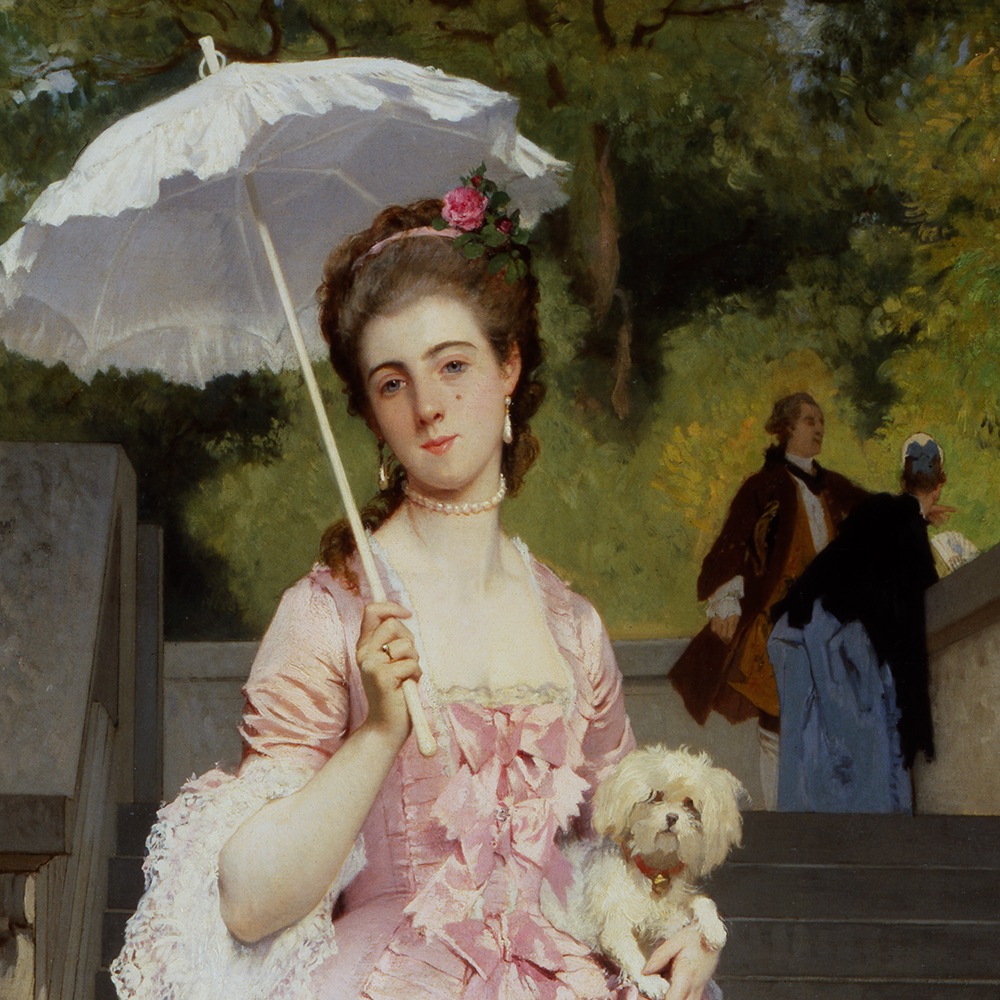

Midday Stroll

Oil on canvas

38 x 26 inches

Signed & dated 1874

BIOGRAPHY - Joseph Caraud (1821 - 1905)

Early in his career Joseph Caraud was inspired, like many other artists, by Italy and Algeria, basing his early Salon entries on his experience in these countries. But as his career progressed he became more interested in anecdotal, genre scenes in which elegant women in their luxurious clothing with sumptuous patterning recalled the eighteenth-century style and rendering of details found in paintings by Fragonard, Greuze, and Watteau.

Joseph Caraud was born on January 5th, 1821 in Cluny, in the Saône-et-Loire region of France. Even before he began his artistic training at the École des Beaux-Arts, he exhibited his first work at the Salon of 1843: La Bonne Maman et La Petite Fille (The Good Mother and the Little Girl) and Portrait de M.G. (Portrait of M.G.). In October of the following year he entered the École des Beaux-Arts ateliers of Alexandre Abel de Pujol, a former student of Jacques-Louis David, and Charles-Louis Lucien Muller, a historical and religious scene painter, in Paris, both of whom influenced his early work at the Salons. From 1843 to 1846, he submitted several portraits to the Salon, perhaps to earn money for a trip to Italy since starting in 1848 he began submitting imagery based on Italian themes. As both of his masters were also portrait painters, he was first introduced to portraiture while he studied with these artists. His first work based on Italian life was his entry for 1848 entitled Jeune Fille Italienne à la Fontaine (Young Italian Girl at the Fountain) and Italien Offrant un Bijou à une Jeune Fille (An Italian Offering Jewelry to a Young Girl). After absorbing the influence of Italian life, he traveled to Algeria, exhibiting at the Salon of 1853 Intérieur d'une Maison Maure à Alger (Interior of a Moorish House in Algiers) and Femme d'Alger Agaçant une Perruche (Algerian Woman Irritating a Parakeet), and Baigneuses Mauresques (Moorish Bathers) thereby maintaining the romantic interest in such themes largely initiated earlier by Eugène Delacroix.

These two journeys, when examined together, interestingly reveal that during his early period Caraud was influenced by several elements. On one hand he traveled to Italy, perhaps under the influence of his École des Beaux-Arts teacher Abel de Pujol – who was interested in mythological and biblical scenes - since Italy was still where many artists went to study the old Italian masters and learn about landscape painting. The Prix de Rome given by the Académie continued to encourage students to seek out this country for artistic inspiration. Additionally, he went to Algeria, thus linking himself with Orientalism, or the craze for everything "oriental". As France became more interested in establishing herself as a colonial power it encouraged artists to travel to North Africa. Here artists would find an entirely new environment and culture, and many would remain consistent painters of this theme throughout their career.

While Caraud initially dabbled in many other sources of inspiration, it is clear that by the Salon of 1857 he had left Italy and Algeria behind him and had started working more on the scenes for which he would be remembered – historical and anecdotal paintings heavily influenced by the period of Louis XV and the life of Marie Antoinette. In 1857 he exhibited La Reine Marie-Antoinette au Petit-Trianon (Queen Marie Antoinette at the Petit Trianon), among others, showing a scene directly inspired by this historical period. He received his first medal, third-class, at the salon of 1859 when he exhibited Representation d'Athalie devant le Roi Louis XIV par les Demoiselles de Saint-Cyr (Representation of Athalie before King Louis XIV by the Young Girls of Saint-Cyr), among two others, and received another medal, this time a second-clas s award, in 1861 for works which included those based on religious activities.

His works, reminiscent of the eighteenth century themes and style, are in sharp contrast to the prevailing sense of Realism imbued in many works of this period in France which sought to document daily life in the country. These Realists artists based their compositions around a dark palette and did not shy away from depicting even the gloomiest scenes of Parisian existence. For Caraud, his decadent images focus on the pomp of the upper bourgeoisie, rendering each detail in a precise fashion, taking great care to picture the fabrics worn by his subjects, a preoccupation that stems from earlier masters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was written of this work that, "He marvelously renders the dress, furniture, looks and types. All of his powdered, musk-scented, and ribboned subjects seem to come out of the Trianon." (Annales de l'Académie de Mâcon, 1881, quoted in Le Base Joconde) Caraud may have also been influenced by the Realists, but until more of his work is brought to light, further exploration of his themes remains conjectural.

In spite of any possibility of his work on Realist themes, he still became best known for anecdotal scenes based on the eighteenth century. These themes resonated with both Salon juries and the public. The demand for his images became so great that they would later be reproduced as engravings for dissemination among the masses, so that each person, who wanted one, could have a Caraud hanging in their home. His interest in the beautiful woman is similar to his contemporary James Tissot, who, early in his career painted fashionable women in historical costume pieces. Philip Hook (Popular 19th Century Genre Painters: a dictionary of European Genre Painting, Woodbridge: Antique Collector’s Club, 1986, pg. 295) wrote that:

The eighteenth century assumed an almost mythic significance for bourgeois Europe of a hundred years later…The artist G.A. Storey claimed ‘There can be no doubt that want of taste in dress and other surrounding often obliges the artist to present his fancies in the costumes of periods when articles of clothing were in themselves works of art, instead of in the shifting fashions of the day that in a year or two not only look out of date, but stand forth in all their native ugliness and vulgarity.’

In 1867 he was given France's highest honor and named a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur. He also participated in the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris where he earned a bronze medal. Caraud continued his involvement in the Parisian Salons and exhibitions until 1902 when he exhibited Jardin des Tuileries (Tuileries Garden) for his final showing. He died in 1905 – the exact date is unknown.

In his work inspired by eighteenth century genre scenes, Caraud found a sympathetic audience and became a very ”in-demand” artist attested to by the fact that many of his most popular paintings were widely reproduced to meet public anticipation. But more of his work will need to be brought to light before a fuller assessment of the possible diversity of his oeuvre can take place. Nevertheless, his placement in the annals of nineteenth century anecdotal painting is assured.

Much of his work is in private collections but can also be found in the following museums: Musée Ochier à Cluny - Portrait de Madame Fauconnier (Portrait of Madame Fauconnier); Musée de Tessé in Le Mans – Jeune Fille Tricotant (Young Girl Knitting); Musée des Ursulines in Macon – La Lettre (The Letter); and the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Laurel, Mississippi - The Letter.