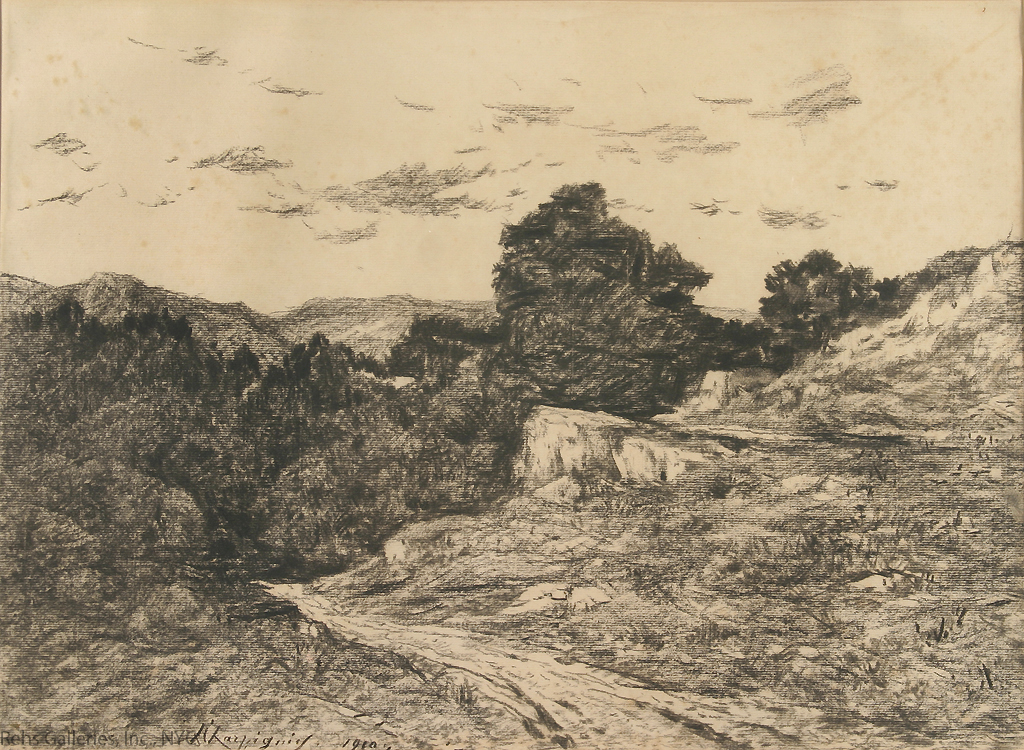

Henri Joseph Harpignies

(1819 - 1916)

Landscape

Black chalk on paper

15 1/43 x 20 1/2 inches

Signed and dated 1910

BIOGRAPHY - Henri Joseph Harpignies (1819 - 1916)

[Harpignies] is a master of form, and has long been a force in the development of landscape painting, and much of what is best in it now is traceable to his influence, especially in regard to drawing and composition.

- William A. Coffin, The Century, 1898, pg. 395

Henri-Joseph Harpignies’ life extended beyond the span of many artistic movements in France. During his youth the Barbizon painters were challenging the classical landscape tradition and forcing the public to recognize that landscape painting should be appreciated as an art equal to that of historical or mythological painting. During the latter half of his life the movement of Realism was still exerting its hold over artists, influenced by the social situations of the day, and Impressionism and later Post-Impressionism began their own search for new representations of landscape and its effects. While Harpignies began his public career rather late in life, comparatively speaking, he clearly was most affected by the earlier interests espoused by the landscape painters of the first half of the nineteenth century, mostly Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Harpignies lived through a number of changing styles but remained steadfast in his appreciation of landscape painting and especially views of Italy of which he wrote that “It was Rome which found, created, sustained me-and which sustains me still; it is to Rome that I owe not only my most noble emotions by my finest inspirations. That is what should be said above everything, that all who desire to learn can go there and face to face with beauty realize how enchanting it is.” (quoted in Lorinda Munson Bryant’s French Picture and Their Painters, London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1923, pg. 183) With its classical connotations, Rome became the primary source of inspiration for Harpignies who became a master landscape painter in the tradition of Corot.

Henri-Joseph Harpignies was born July 24, 1819 in Valenciennes. His parents were of Belgian origin and came to France and established a sugar beet factory in Famars around 1825, working in this as well as a number of other jobs. The first years of his life were spent alongside his father, mother, and also his uncle, in the middle of a bourgeois lifestyle which had been cultivated by his father’s many commercial exploits. It was also here that he gained an appreciation for nature, writing, “Already nature pleased me, the sun and the beautiful days made me happy. I often sketched on paper trying to reproduce what I saw.” (Henri Harpignies: 1819-1916, ex. cat., Valenciennes : Musée des Beaux-arts, 1970, pg. 12)

Harpignies began to draw at the early age of four and began his schooling in 1830 at the College Communal in Valenciennes where he only excelled at drawing, music, and geography. (Henri-Joseph Harpignies: paintings and watercolors, ex. cat., Memphis: The Dixon Gallery and Gardens, 1978, pg. 6) At school, from the age of 14 he received several first place prizes for drawing contests that were held, furthering his desire to become an artist. Around 1838, after he had finished his studies, he came into contact with a doctor who was returning to Egypt, and who also knew Jean Achard. He encouraged him to travel, and thus Harpignies began a tour of France, visiting Paris, Orleans, Tours, Nantes, La Rochelle, Toulouse, among other cities. He was gone only two months but the journey left a great impression on him and inspired his interest in painting.

Despite this, Henri’s father’s intention was to turn him into a businessman and for the first several years of what could have been the beginning of his artistic training, Henri traveled from city to city, representing his father’s firm. His artistic training not completely forgotten, Henri also enrolled in drawing lessons which were very useful and taught him how to copy realistically. His father finally realized that he was not going to become the businessman/engineer he hoped his son would become and, in 1846, he gave him a stipend of 150 francs a month to help him fulfill his artistic ambitions. Henri left for Paris where he began his first artistic studies, at the mature age of twenty-seven, under the landscape painter Jean-Alexis Achard. Throughout his entire life he regretted not beginning his artistic studies earlier, knowing that since he was a young boy he knew he wanted to become an artist.

The Revolution of 1848 broke out shortly after Harpignies’ relocation to Paris. To escape the tumultuous events that were plaguing the city, he fled to Famars where his family remained and the next year began traveling with his teacher Achard to Brussels, Belgium, where they stayed for a year. But Harpignies wrote disparagingly that “the beer every night was bad business for painting (Henri Harpignies, pg. 22). Tired of Belgium, his father allowed him to go to Baden-Baden Germany, a region with rich landscapes. Still, Harpignies’ time in Germany did not bring him great satisfaction. Instead, under the advice of many, he left for Rome in November of 1850, following his tenet that “All if for art, all for the beautiful…” (Harpignies, pg. 23) In a direct statement to the other French artists working in other styles who rejected the associations that Italy had with the classical tradition of the Salon, Harpignies wrote (quoted in Bailly-Herzberg, Janine, L’Art du Paysage de l’Atelier au Plein Air, Paris: Flammarion, 2000, pg. 176):

Ah, makers of pigs’ ponds and of boatmen, intransigent realists, painters of the banks of the Marne and of the Oise and other trite everyday subjects, come and see the valley of Poussin… there you will see real landscapes.

Harpignies was clearly not following in the footsteps of his contemporaries, many of whom were committed to rural landscapes populated with animals, or with gritty realistic themes from the everyday scenes of Parisian life. He was not to be associated with either the Barbizon or Fontainebleau school, saying “No! No! No!, It’s Rome that marked me above all.” (Harpignies, pg. 27) He sought the idyllic offered to him by landscape painting reminiscent of earlier masters such as Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorraine.

After Rome, Harpignies left for Naples, originally meant to be a six day trip, but which turned into a six month residency. He traveled to Capri where he found the “enchantment of enchantments” (Harpignies, pg. 27), and also saw Mount Vesuvius, of which he executed a number of paintings. After spending time in Naples and its environs, he returned to Rome and remained there through the winter of 1851 and into 1852. He never stopped saying that “I would stay here my entire life if my father had not called for my return.” (Harpignies, 27)

Returning to Famars, then Paris, in the spring of 1852, Harpignies debuted at the Salon of 1853, when he was thirty-four years old, with three paintings, of which Vue Prise dans l’Île de Capri, Golfe de Naples (View From the Island of Capri, Gulf of Naples) was one. During the next year the itinerant artist traveled once again, this time to Marly, the Forest of Fontainebleau, and the Pyrénées, among many other locations. While he spent a significant amount of time in and around the Forest of Fontainebleau, where the Barbizon School flourished during the earlier decades, he was very loosely associated with the Barbizon artists, finding the greatest inspiration in the work of Corot. Harpignies showed an affinity with nature and took a special interest in the rendering of trees to such a point that Anatole France, a great writer of the period, named him the Michelangelo of trees.

Harpignies’ interest in landscapes and especially views of Italy continued unabated and he returned once again - to this country - in 1863 and remained there until 1865, during which time he met Corot whose work he became very fond of and whom he would follow throughout his entire life. Harpignies wrote that (quoted in Bailly-Herzberg, pg. 177):

It’s there [in Italy, where he lived “in a perpetual ecstasy”] that I finally understood it, it was my guide during all of my career. If father Corot could read me, he would be very happy, since he was always Italian, the greatest landscape painter of modern times.

Working in Italy was in the grand tradition of historical landscape painting, admired by Salon juries. Thus it is curious to note that one of Harpignies’ paintings was rejected at the Salon of 1863. While this was one of the last harsh and selective juries, Harpignies work and theme did not challenge many preconceived notions of what landscape painting should be. This demonstrated the level of exclusion of the dismissive Salon juries. Harpignies was so distraught that he destroyed the rejected painting and fled to Italy to assuage his feelings of rejection.

Between 1864 and 1866 Harpignies exhibited watercolors at the Salon, each depicting different views of the Italian landscape. His curiosity about other media began early on in his career under the influence of Achard, who was also an engraver. In 1847 he began experimenting with engraving and by 1851 began working regularly in watercolors. It was not until 1864, however, that he began to exhibit at the Salon des Aquarellistes and not until 1881 that he was elected a member of the Société des Aquarellistes Français. He also began selling his watercolors to art galleries in both New York and London, accumulating about 70,000 francs per year on these commissions alone. Of his watercolors Henri Marcel in La Peinture Française au XIX Siècle (Paris: Alcide Picard & Kaan, 1903, pg. 272) wrote that, “…the watercolors of Harpignies, his views of Paris for example, are the summarized notations of an impeccable surety, where the reserved whites of the paper provide extreme depth and lightness.” Throughout his career Harpignies would exhibit many watercolors, and also exhibited at the New Watercolor Society in London.

In 1869 Harpignies retreated occasionally to the village of Hérisson in the Yonne region of France. In 1878 he acquired a property at Saint-Privé and also began spending winters in the Côte d’Azur from 1885. He set up his own studio which was full of light. Students soon came to work alongside him and at every chance, they went into the countyside together. Harpignies was not just their teacher, but a friend to each of the students. Here in the Yonne region, he could fully realize the aspect of nature which was foreign to a Parisian lifestyle. Still, he continued to maintain his Parisian ateliers.

This same year he was also proclaimed “hors concours,” exempt from having to submit his work for Salon jury approval. This was only the beginning of a long list of accolades that were to be bestowed upon him. In 1875 he was named Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, was given a second-class medal at the Exposition Universelle of 1878, and already by 1883 was promoted to the position of Officier de la Légion d’Honneur, only to be promoted again to position of Commander in 1901. By 1911 he had become a Grand Officier.

His list of awards did not end there. He continued to submit to the Salon exhibitions - in 1897 was given the Medal of Honor for Les Bords du Rhône (The Banks of the Rhône) and Solitude (Solitude) – paintings previously rejected by the Royal Academy of London. This was an exceptional award since it was rare for a landscape artist to receive such high praise. In 1900 he obtained the Grand Prix at the Exposition Universelle, where his talent was represented by a series of oils and watercolors, including La Loire (The Loire), Solitude (Solitude), Souvenir de la Côte d’Azur (Souvenir of the Côte d’Azur), among several others. He also was a member of the Salon jury eight times during his career.

He submitted to the Salon until 1913 when he exhibited Vallée de Castellar; environs de Menton (Castellar Valley; environs of Menton) and Oliviers à Menton (Olive Trees at Menton). He continued to paint until his death on August 28, 1916, despite being almost blind. He died in Saint-Privé, Yonne at ninety-seven.

While Harpignies was clearly inspired by the earlier master Corot as well as by the classical tradition based on his extensive travels through Italy, he was not completely outside the influence of his contemporaries, even if he may have preferred not to be classified with them. This is clearly outlined in a critique by Ernest Chesneau (L’Art et Les Artistes Modernes en France et en Angleterre, Paris: Didier et Cie, 1864, pg. 195 ) in which he wrote:

For Mr. Harpignies, it is too clear that he is content to nature’s perceived impressions. The impression completely true,, I don’t mind admitting it, but it is only an indication of a painting to be finished and not a completed painting. Let us add that the impressions of Mr. Harpignies…have, without doubt, much merit. However,…he so simplifies the difficulties that this merit is used almost is almost wasted.

Even though he did not associate himself with the Impressionist group and even though he professed his admiration for Corot and Italy, Harpignies still fell under the same scrutiny as did the emerging group. This suggests that his execution was influenced by the changing styles of the artistic movements in France.