Henri-Jean-Jules Geoffroy

(1853 - 1924)

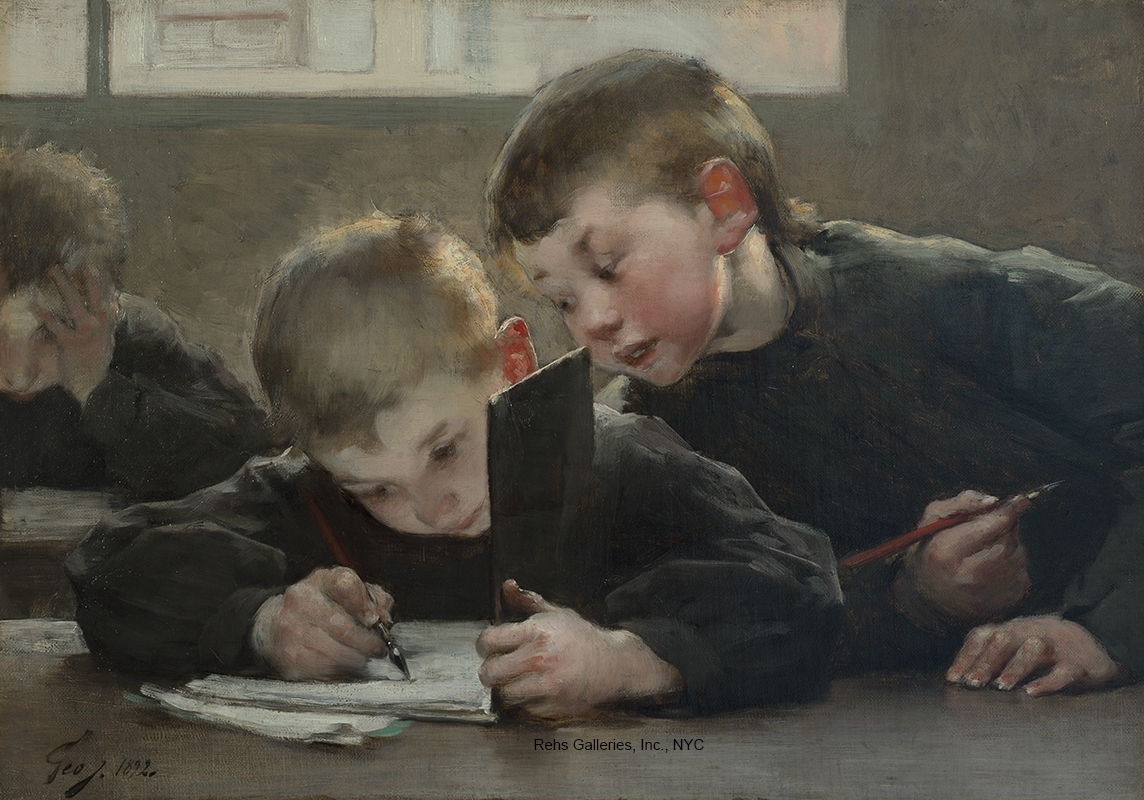

Un jour de composition

Oil on canvas

13 x 18 inches

Signed and dated 1892

BIOGRAPHY - Henri-Jean-Jules Geoffroy (1853 - 1924)

It is rare that a consequential painter’s childhood is as unknown as that of Jean Geoffroy. He was born on March 1, 1853 in Marennes, a fishing port on the western coast of France, and left there sometime after the birth of his brother, Charles, on February 5, 1855. Charles died seventeen months later in the sixth arrondissement of Paris in the summer of 1856. Why, or precisely when, the Geoffroys moved to Paris remains unknown.

Geoffroy’s parents are somewhat better documented. His father Jean-Baptiste (1823-1895) was a costume designer and his mother Rosalie (1826-1911) was the daughter of the English painter, John Dickinson. [i] Dickinson himself moved from Manchester, England to Marennes, perhaps in search of scenic subjects for his art. Once there, he had four children with a local woman before marrying her and producing four more. Sadly for Rosalie, she was the oldest of the children and thus, the subject of social ostracism before of the circumstances of her birth. It may be that the Geoffroy family’s move to Paris was a means of removing themselves from an unwelcoming social environment. In addition, it is possible that Jean-Baptiste’s professional prospects would have been better served by the economy of a larger city.

Once the Geoffroys moved to Paris, little is known of their family life. They had no more children, and there is no record of their address beyond the death notice of the infant Charles in the St. Germaine neighborhood on the left bank of the city. Based on scant references to Rosalie’s involvement in her son’s life, it would appear that she and Jean-Baptiste did not live together more than a few years.

Jean Geoffroy’s name appears eleven years later as a student at the municipal school of design and sculpture. He was fourteen years old. The school was located at 37 rue Volta in the third arrondissement north of the Marais district. At that time, it was a working class neighborhood, and the school was established to train young men who were already employed at various other jobs during the day. Classes were held in the evenings and the funding for their education was underwritten by the City of Paris and Ministry of Public Education. The Ministry’s goal was to educate fifteen to twenty-five year old youths as decorative painters, porcelain designers, industrial designers, printmakers, engravers and lithographers. [ii] The director, Eugène Levasseur (1822-1887), had accepted his post in 1854 with the specific intention of expanding the educational program so that working class boys would have the opportunity to earn decent wages and be productive citizens of the Second Empire. This objective, which had its roots in the eighteenth century writings of Enlightenment philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) would eventually become a key element in Geoffroy’s purpose as a painter. [iii]

The young Geoffroy seems to have done well at school. In 1867, his first year there, his drawings were included in an annual exhibition reviewed by the emperor Napoleon III. The exhibition listing for him read: “the student Geoffroy, age 14 and a half, decorative painter: One composition executed in 3 hours and one flower drawing from nature executed in 8 hours.” [iv] Speed of execution would have been an important skill for a designer hoping to obtain a job with one of the manufacturing enterprises of the time.

The question of why the fourteen-year-old Geoffroy was sent to this school remains a matter of speculation. It is quite possible that he had a natural inclination for drawing, but there must have been a responsible adult who helped him apply to the school initially, whether it was his mother or another relative. Dominque Lobstein, art historian and author of several major publications on Geoffroy, has suggested one possible response to that question in his book, Jean Geoffroy dit Géo. Perhaps Geoffroy was in touch with some of his Dickinson family relatives who were artists; his aunt Alice Dickinson (1833-1888) was married to the painter Jean Benjamin Serres (1832-1876), and his cousin Elisa (1856-?) married the painter Alexandre Juglas (1843-?). Perhaps his grandfather John Dickinson was still alive and in contact with his daughter and grandson. [v]

Regardless of Geoffroy’s puzzling family history, he emerges in 1870 living on his own at 48, rue du Faubourg-du-Temple in the eleventh arrondissement, just a few blocks northwest of the Place de la République. Among his neighbors was a middle-class couple, Louis and Julie Girard, who operated a private school, the Institution Girard. This day school for boys occupied half of the ground floor of the building; Geoffroy’s modest apartment was on the top floor. Although only seventeen himself, he found a number of his models among the young students who were continually gathering in the courtyard and adjacent streets. Louis Girard and Geoffroy quickly developed a wholehearted friendship that would last a lifetime, and that would provide the artist with a sense of family unlike any that he had previously known.

The following year, in 1871, Geoffroy signed up to audit some courses at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Clearly, he had decided to pursue more formal training as a professional fine arts painter rather than as an “peintre décorateur”. The free audit, which only lasted three weeks, was presumably a marketing strategy to offer potential students a glimpse of the art education available if and when they could afford it. [vi] For Geoffroy, however, Napoleon III’s declaration of war against Prussia in 1870 meant that further education was postponed, at least for the immediate future. It seems unlikely that Geoffroy had the means to flee Paris during the Commune, and it may have been during these months that his political philosophy began to take shape; it would have been difficult to ignore the cannon fire from the nineteenth arrondissement next door or the pitched battles in the streets of Montmartre. Paris was in crisis. By the end of the war, the revolutionary values of “liberté, egalité, fraternité” had been crystalized both by the civil war of the Commune and the occupation of France by Prussian troops. Geoffroy would be steadfastly linked with the social causes of public education and public health from that point forward

The early 1870s, following the end of the Franco-Prussian War, was a time of chaos, not only for the government but also within the art community. Dissatisfaction with the official Salon had been brewing for a decade or more, and the disruption of the war forced many young artists to examine their own positions about the future of art. The group that would become known as Impressionists proclaimed their freedom from officialdom with an independent exhibition in 1874; and although the core group of Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro and Pierre Renoir were the instigators of this effort, the majority of the participants were Realist painters who had been fighting for aesthetic acceptance since the 1860s. Geoffroy shared the interests of the Realists in the social issues afflicting the poor and disenfranchised, but the formal challenges of modernism were of little concern to him. In this respect, he combines the traditional painting techniques with what was then considered a radical social agenda.

In 1874, he made his Salon debut, and he also began working as an illustrator for Paris Illustré in order to pay his bills. Simultaneously, he continued his art education, first with the designer Eugène Adan (1826-1884) and then with the academic painter Emile Jean-Baptiste Bin (1825-1897). For Geoffroy, Bin’s atelier offered not only instruction in painting, but also encouragement to think for himself; the middle-aged Bin had fought with the republicans on the barricades in the revolution of 1848 and again in 1851, and he was also an admirer of James McNeill Whistler and Edouard Manet. In short, he taught an academic approach to painting, but nurtured a spirit of curiosity and aesthetic exploration in his students. Geoffroy continued to study with Bin until 1886.[vii]

During the mid-1870s, Geoffroy also met Jules Hetzel (1814-1886), editor, publisher and ardent républicain. Like Bin, Hetzel had fought against the monarchy of the Second Empire, and had exiled himself to Brussels until after the end of the Franco-Prussian War. On his return to Paris, he began to publish presumably scandalous poems by Charles Baudelaire and the socialist essays of Gustave Courbet’s friend, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. From Geoffroy’s perspective, however, the most important publications were the children’s books that Hetzel hired him to illustrate.

Geoffroy’s work as an illustrator of children’s literature reveals his consummate talent at capturing images of childhood. Although the children’s faces are typically innocent and open, their physical poses often suggest more individualistic qualities—the determined walk of a toddler in pursuit of her buggy or the comic poses of a group of girls learning how to “manage” their umbrellas. There are also children in trouble or despair—dressed in filthy rags and depicted in a straightforward Naturalist style.

As he was developing his skills as an illustrator for Hetzel, Geoffroy also experimented with his personal signature. In 1877 and 1878, he signed his work as Jean Dickinson, a French version of his English grandfather’s name, John Dickinson. Again, this raises the question of his grandfather’s possible role in the young painter’s life. There is no evidence that Geoffroy had any contact with his parents after 1871, but this signature could also have been meant to honor his mother and her family. A few years later, around 1880, the painter began to sign his works as Géo, the nickname by which he is still known today.

In 1879, Geoffroy’s supply of child models expanded considerably when the Institute Girard run by his adopted family opened a boarding school near their home at 54 rue du Faubourg du-Temple. Suddenly, the painter had an abundant and ever changing supply of children who might serve as inspiration for his work. Some of them can be seen in the 1880 painting, Un Future Savant (A Future Scholar), Geoffroy’s Salon entry for that year. Paintings from the early 1880s tend to be focused on a small group of figures or even a single child such as Un Malheureux (An Unhappy Child), but as Geoffroy built his reputation and skill, he received more commissions for large, multi-figure compositions. This new development was undoubtedly fostered by his participation as a member of the Commission on Educational Imagery beginning in 1882. In this capacity, the artist contributed to decisions about how images could best be used as teaching tools in the classroom. Increasingly, his own work focused on educational access for all children; and in 1885, he became an Officer of Public Instruction, one of the highest honors awarded by the French educational system of the time.

Likewise, his work as a painter began to attract more and more attention. In 1883, he received an honorable mention at the Salon des artistes français; and in 1886, he received a third class medal as well. In 1887, with well over a decade of public service to public education as well as a track record of excellence in painting, Geoffroy was recognized as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. At the age of thirty-four, the working class boy from Marennes had not only been acknowledged for his contributions as an artist, but also as a committed advocate for children.

Geoffroy’s world came to a dramatic halt in 1890 with the sudden death of Louis Girard, his friend, neighbor, and in all likelihood, his surrogate father. Julie Girard was left destitute with two children and almost no resources. Fortunately, Geoffroy was able to purchase a new house in December at 7 rue des Lilas in the far northwestern nineteenth arrondissement. The gate was apparently rusty, but nonetheless the house had beautiful panoramic views from its hilltop site of both Paris and the plains of St. Denis. Although thoroughly urban today, this part of Paris was still somewhat rural in the 1890s, offering residents a quiet, bucolic neighborhood. Mme. Girard and her children made their home on the upper floor of the building and Geoffroy lived on the first level. Three years later, the painter accepted a commission from the Ministry of Public Instruction for five large murals to be displayed at the Pavilion of Education at the Exposition universelle in 1900; this allowed him to purchase some adjacent property, expanding his studio space to accommodate the scale of the new project.

The subsequent years were spent gathering images and information in preparation for the five murals. To that end, he traveled to Algeria and Brittany, sketching extensively to capture images that would depict the critical importance of providing education for all children living under the French flag, whether in Paris or in the colonies. The goal was to demonstrate France’s commitment to education for all people, emphasizing the underlying principle that an educated public will make rationally informed decisions for the good for the nation. Geoffroy won a gold medal for this work at the Exposition universelle in 1900.

In contrast to his public work, Geoffroy’s private commissions focused more and more on images of children at risk from dangerous work such as Ecole professionnelle à Dellys, Travail du fer, an 1899 painting of boys working at an open forge in Belleville. This may have been the result of his growing involvement in public health issues, which came to his attention because of the need to educate the public about new sanitary practices such as sterilization. In particular, Dr. Gaston Variot, founder of the Belleville Clinic, and one of Louis Pasteur’s research collaborators on sterilization, sought out Geoffroy for his assistance. Variot had long advocated for the sterilization of milk as a way to reduce the infant mortality rate, but he struggled to find a way to convey that message effectively to the public. [viii]

In 1903, Geoffroy showed Variot his large triptych L’oeuvre de la Goutte-de-Lait,(The Work of a Drop of Milk), a monumental composition intended to inform the public about the benefits of sterilized milk through a clear visual narrative. The left panel shows a newborn baby being weighed shortly after birth; the central panel is full of healthy children and smiling mothers who surround a new mother as she listens carefully to the doctor’s advice about using sterilized milk; the right panel shows the young mother receiving her supply of sterilized milk in a bottle. The painting was shown at the Salon of 1903 and subsequently purchased by the state; it was on exhibit at the Petit Palais until 2016 when it was transferred to the Musée de l'Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris.

Variot and Geoffroy became close friends as a result of their collaboration on these public health issues. Together with Variot’s wife and daughter, they dedicated themselves to a variety of public health campaigns, always with an emphasis on assisting the poor and working class people on how to improve the quality of their lives.

One other painting that deserves comment from this period is a scene of a young woman giving up her newborn child to an orphanage, A l’hospice des Enfants-Assistés, l’abandon d’un enfant. This canvas dates to 1912, the year after Geoffroy’s mother Rosalie died. She had been living close to her son’s home in the nineteenth arrondissement for some years, thus raising again the question of whether there was any contact between them prior to her passing. The subject of the painting is unusual in the artist’s work and may represent his own apparently mixed feelings about his mother’s death.

The onset of World War I created a fresh set of circumstances for the painter. He continued to receive numerous commissions, but the subject matter from these years is more light-hearted. Although this may seem surprising in the middle of such an intense conflict, it may have been one way to offer an alternative to the persistently grim horror of the news from the trenches.

Following the war, Geoffroy traveled frequently with Dr. Variot. both to regional hospitals where he would provide images for teaching patients about new health practices and occasionally simply on holiday to Variot’s country home in Brittany. On one of these trips, Geoffroy returned to the region where he was born, probably for the first time since his family’s departure in the 1850s.

As he approached the beginning of his seventh decade, Geoffroy turned his attention to working in charcoal on paper, pastels, watercolors and lithographs. Children continued to be his primary subject. The images are freely drawn or painted, often featuring a single child who is completely absorbed in a particular activity.

Geoffroy died after short illness in the Clinique Velpeau, 7 rue de la Chaise, on December 15,1924. He left everything to Julie Girard, who continued to exhibit his work at Galerie Georges Petit. Mme Girard also commissioned a bas-relief for his tomb at the Pantin Cemetery near their home. On December 22, 1924, La Presse published Geoffroy’s obituary, noting that “...this grand worker died with his palette in his hand. He has the deepest respect from his public. He did not look to shock or scandalize; his sole ambition was to be an honest artist and worker. And the public will forever regard him with the sympathy that his compositions evoke.”

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles, California

Centre national des Arts plastique, Paris-La Defense

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Hôtel de Ville, Marennes, France

Maison de Victor-Hugo, Paris

Ministère de l’Education nationale, Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche, Paris

Musée Anne-de-Beujeu, Moulins, France

Musée Bernard d’Agesci, Communauté d’Agglomération du Niortais, France

Musée Baron Gérard, Bayeaux, France

Musée d’art et d’histoire, Rochefort, France

Musée de l’Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris

Musée de l’Echevinage de Saintes, Saintes, France

Musée de l’Illustration Jeunesse, Moulins, France

Musée de Picardie, Amiens, France

Musée des beaux-arts et Musée Marey, Beaune, France

Musée des beaux-arts, Cambrai, France

Musée des beaux-arts, Dijon, France

Musée des beaux-arts, Mulhouse, France

Musée des beaux-arts, La Rochelle, France

Musée des Ursulines, Mâcon, France

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Musée du Faouët, Le Faouët, France

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Musée du Faouet, Le Faouet, France

Musée national de l’Education, Rouen

Musée Sarret de Grozon, Arbois, France

Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Paris

[i] Some earlier accounts of Henry Jules Jean Geoffroy’s life have suggested that his father was the painter Jean-Baptiste Geoffroy rather than the costume designer. However, the painter Jean-Baptiste Geoffroy died in 1845 and could not possibly be his father. See the Getty Research Institute’s Union List of Artists Names (ULAN). http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/ulan/

[ii] Dominque Lobstein, Jean Geoffroy dit Géo, “Une oeuvre de généreuse humanité” 1853-1924, Exhibition catalogue (Saintes, France: Le CroÎt vif and Musées de la ville de Saintes, 2015) 27.

[iii] For more information on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s influential thinking on education, see his seminal publication, Émile, ou de l'éducation, originally published in 1792. A recent English translation was published by Hardpress Publishing in 2012. Geoffroy is likely to have been familiar with this book later in his career when he became personally involved in the cause of public education for all French children.

[iv] Lobstein, 27. [...“l’élève Geoffroy, âgé de 14 ans et demi, peintre décorateur: une composition esquisse exécutée en 3 heures et une fleur d’après nature, exécutée en 8 heures.” Translation by the author.]

[v] Lobstein, 27, Note 6.

[vi] See Henri Frantz, “Jean Geoffroy” Le Figaro illustré, mai 1901: 1-24.

[vii] By the time that Geoffroy completed his studies in 1886, Emile Bin was the mayor of the eighteenth arrondissement (Montmartre) where he also continued to teach painting. Among his other students were Charles Léandre, Henri Rivière and Paul Signac. It seems probable that Geoffroy would have known these artists as well

[viii] For a discussion about the history of infant mortality rates, see Lawrence Weaver, “Infant Mortality, Infant Feeding and Infant Growth” for the University of Glasgow Department of Child Health and Centre for the History of Medicine at: http://www.who.int/global_health_histories/seminars/