Georges Croegaert

(1848 - 1923)

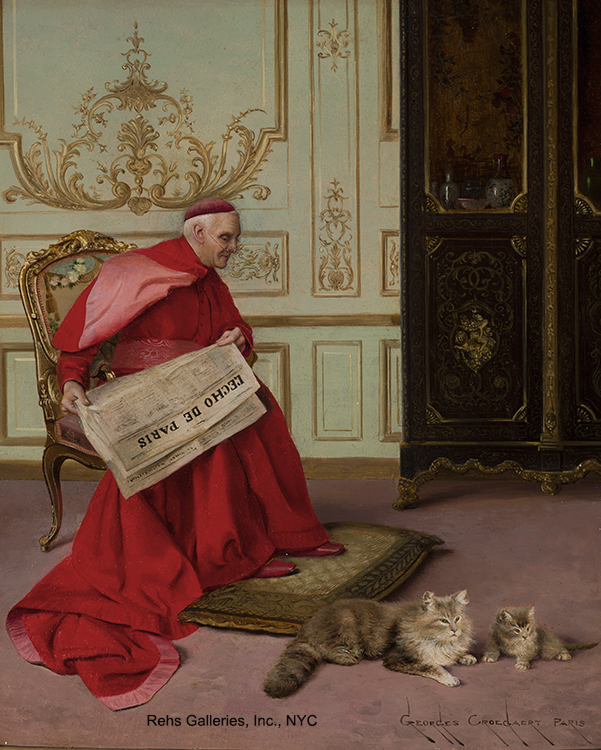

Distractions

Oil on panel

10 5/8 x 8 5/8 inches

Signed

BIOGRAPHY - Georges Croegaert (1848 - 1923)

Facts about the Belgian painter Georges Croegaert are quite meager. The first twenty-eight years of his life were spent in his native Belgium, but we know only that he was born in Antwerp and received his art education at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts there. Assuming that Croegaert began his schooling at the Academy in the early 1860s, he would have been part of a young generation that embraced Realism and was eager to define a new national identity for Belgium as an independent nation. [i] This decade was a time of profound change in the visual arts in Belgium.

Although Realism in Belgium has generally been understood as an offshoot of the French Realist movement, it had, in fact, begun in the 1840s with a group of young artists studying at the Atelier Libre Saint-Luc in Brussels. This group included Félicien Rops, Constantin Meunier, Louis Artan, Charles DeGroux and Camille Van Camp, all of whom would become ardent proponents of the Realist movement. When Gustave Courbet’s painting, The Stone Breakers, was exhibited at the Brussels Salon of 1851, it was not only an inspiration for young painters, but a confirmation of the ideas they had already embraced.

At the Royal Academy in Antwerp where Croegaert studied, Courbet himself was invited to give a lecture in 1861. The response from the local press was cordial, but telling in its gently satirical description of the Realist master’s painting ofThe Burial at Ornans as The Burial of Romanticism. [ii] In other words, the Belgian Romantic artists, who had once been seen as revolutionary in their rejection of French Neo-classicism, were now being supplanted by the emerging generation of Belgian Realists.

Regardless of the enthusiasm for Realism, the curriculum at the Royal Academy remained solidly grounded in the traditional practice of learning to draw, first from plaster casts of famous artworks, then from objects and ultimately from live models; only after having mastered drawing would students learn how to paint. [iii] There can be no doubt that Croegaert mastered these skills successfully. His ability to render human figures in convincing three-dimensional poses testifies to his classical training, as does his sophisticated understanding of composition.

After completing his formal art education, perhaps in the late 1860s, Croegaert established himself as a portraitist and genre painter. He frequently painted portraits of young society women, which seems to have been his primary focus during this time. Much of Croegaert’s work is undated, but the stylistic changes over time provide a frame of reference for his development as an artist. His attention to the texture of fabric and objects as well as his impeccable composition must have made him a sought-after portrait painter. It is likely too that he knew the work of Alfred Stevens (1823-1906), the renowned society portraitist who exhibited regularly at the Salon in his native Brussels as well as in Paris. Perhaps it was Stevens’ example too that inspired Croegaert to consider a move to Paris as a means of developing his career. The eruption of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 kept Croegaert at home in Belgium for a few more years, but in 1876, he packed up and left for the French capital.

Once settled in Paris, Croegaert continued to work as a portraitist and as a genre painter. The influence of the Impressionists is visible in many of his works from the late 1870s and the 1880s. In two canvases from 1885, both titled Flirtation, he depicts a young couple picnicking by the river as friends row off downstream in a flatboat. These are not society denizens, but rather working-class men and women enjoying an outing on the riverside. The handling of the landscape echoes the style of Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot rather than that of Pierre-Auguste Renoir or Claude Monet, but the Realist theme of ordinary people going about their daily lives is very much in keeping with the Impressionists’ chosen subject matter.

During the 1880s, he also continued to portray young society women in beautiful gowns and luxurious settings. Japoniste elements, such as fans and screens, make increasingly frequent appearances in these paintings, echoing the extraordinary long-lived fascination for all things Japanese. In the 1889 painting, A Difficult Decision, Croegaert offers something of an Orientalist extravaganza as two women try to select a silk fabric while seated on velvet sofa surrounded by a collection of Japanese swords, Chinese tapestries and a genuine tiger rug beneath their feet. It almost seems that Croegaert was gently poking fun at the sheer implausibility of the quasi-exotic environment in which the women were seated.

Croegaert made his Paris Salon debut in 1882, and exhibited regularly up until 1914, when the annual show was curtailed by World War I. Salon catalogues during the nineteenth century reveal that Croegaert was living in Montmartre during these years. Initially, he rented space at the rue Gabrielle 51 close to the top of the butte and not far from the Moulin de la Galette nightclub painted by Renoir. [iv] In 1898, he moved to the picturesque rue Cauchois, 13, also in Montmartre.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, Croegaert built his reputation as a portraitist and genre painter. He exhibited regularly at the Salon, generally submitting his genre paintings rather than portraits. He also exhibited his work in Brussels and at least once in Vienna in 1888. [v] In addition, his work was handled by Georges Petit Gallery, who did much did much to sell Croegaert’s paintings in England and in the US. He seems to have been especially popular with British industrialists who later donated the paintings to their local museums.

Today Croegaert is best remembered for his humorous paintings of Roman Catholic cardinals shown engaging in all too human activities, a subject that he seems to have adopted after his move to Paris in 1876. The fashion for this subject was initiated by Jean-Léon Gérôme in his 1873 painting, L’Eminence Gris, featuring Cardinal Richlieu’s secretary and confidant, François LeClerc du Trembly, who was known as the “Grey Cardinal”. The painting received very positive critical attention as well as popular acclaim, appealing to the taste for anecdotal genre paintings featuring historical French figures. Unexpectedly, it also spurred an interest in genre images showcasing Catholic cardinals. The following year, Jehan-Georges Vibert began composing less flattering, but more amusing images of the French clergy. The Schism, for example, shows a robust abbot and a red-robed cardinal seated back to back in a velvet armchairs with the remains of a generous lunch on a nearby table. Neither man acknowledges the other and their gestures suggest that they are thoroughly unhappy with each other. The “schism” reveals not theological discourse, but two very sulky prelates who clearly lack a scintilla of charity or patience. [vi]

Together with Vibert and Andrea Landini, Croegaert formed a small group of specialists who developed these comic canvases of religious figures. Later in the century, Marcel Brunery would also take up this particular type of painting. Croegaert depicted cardinals enjoying their cigars, playing cards, inspecting nude models ostensibly on behalf of the artist, enjoying the antics of their cats, and—always—partaking of sumptuous food and drink. Occasionally, they are also shown appreciating artworks and rare books; and in one case, sitting at an easel to paint. Typically, these are narrative paintings, usually lampooning the foibles of the supposedly pious religious leaders. The satire is gentle, but often pointed.

The paintings of cardinals were very popular in the anti-clerical Third Republic of France, and they undoubtedly helped to establish Croegaert as a respected member of the Paris art world. His career seems to have prospered, and by 1900, he had moved from bohemian Montmartre to the rue Bartholdi, 11 in the elegant neighborhood of Bologne-Billancourt near the Bois de Bologne. There is a self-portrait of the artist as a middle-aged man seated at his desk in a very elegant room—perhaps in his new home.

With the advent of war in 1914, life in Paris became increasingly difficult. Like most other artists, Croegaert probably continued to paint, but there is no record of any further exhibitions to date. Nor is there any information about his personal life until his death is recorded in Paris in 1923.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Hartlepool Museums and Heritage Service, Hartlepool, North Yorkshire

Haworth Art Gallery, Accrington, Lancashire

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, Bournemouth, Dorset

Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead, Tyne and Wear

Wigan Arts and Heritage Service, Manchester

[i] Belgium became an independent nation in 1831. It had been part of the Kingdom of the Low Countries following the fall of Napoléon at Waterloo, but obtained its independence only after breaking from Dutch rule in 1830. The so-called “Great Powers” of Austria, Prussia, Britain, Russia, and France supported this development as long as Belgium agreed to remain neutral in any future conflicts. Leopold I of the German house of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha assumed the role of king in 1831, industrializing the new nation and successfully maintaining political neutrality.

[ii] Denis Laoureux, ed., En nature: La Société libre des beaux-art d’Artran à Whistler (Namur: Province de Namur, Belgium, 2013) 12. For an overview of Realism in Belgium, see Janet Whitmore, “Building a Cultural Identity: Belgian Realists and the School of Tervueren” in Toward a New 19th-Century Art (Minneapolis: Books & Projects in association with ACC Publishing Group, 2017) 67-79.

[iii] Antwerp was the primary center of both culture and commerce from the late medieval period until well into the nineteenth century. The Royal Academy of Fine Arts was founded in 1663 by David Teniers the Younger, court painter to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm and master of the guild of Saint Luke, and became the primary school of art in the region. Brussels did not become a major cultural center until after the establishment of the city as the Belgian capital following independence.

[iv] Explication des ouvrages de peinture et dessins, sculpture, architecture, gravure et lithographie des artistes vivants (Paris: Société d’imprimerie et librairie administratives et classiques (Paul Dupont), 1886) 51.

[v] See Dictionnaire des peintres belges at: balat.kikirpa.be/peintres

[vi] Eric Zafran pioneered the study of these “cardinal” paintings in his book, Cavaliers and Cardinals, Nineteenth Century French Anecdotal Paintings (Cincinnati: Taft Museum, 1992). Exhibition catalogue. His work remains a primary source on this subject.