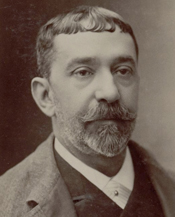

Ferdinand Victor Leon Roybet

(1840 - 1920)

A Cavalier

Oil on panel

51 x 37 3/4 inches

Framed dimensions:

59 1/2 x 46 inches

Signed

BIOGRAPHY - Ferdinand Victor Leon Roybet (1840 - 1920)

Ferdinand Victor Léon Roybet spent his early childhood years in the southern French town of Uzès just a short distance north of Nîmes. This region of France has welcomed myriad groups of people over the centuries, ranging from the ancient Romans who built the Pont du Gard aqueduct there, to the Jews in the fifth century and then to the Umayyad Muslim dynasty of Spain in the early eighth century. By all accounts, it was reasonably peaceful and diverse society until Pope Innocent III declared a prolonged Crusade against the local Cathars in 1209. [i] At the conclusion of this very bloody war twenty years later, the region of Languedoc was incorporated in the Kingdom of France, and the rulers of Uzès became dukes of France. Although the region would again be convulsed by the Wars of Religion in the sixteenth century, it emerged intact after the French Revolution and prospered. During Roybet’s lifetime, the ‘duke’ of Uzès was actually a duchess, who was simultaneously a steadfast monarchist and a close friend of Louise Michel, the ardent leader of the Paris Communards.

Roybet was born on April 12, 1840, the son of Louis Charles Florent Roybet and Françoise Cotte. It is possible that Roybet’s father was a cafe owner and liquor manufacturer in Uzès. In 1846, the family moved to the city of Lyon where the young Roybet began his primary schooling. He must have shown an interest and talent for drawing because he began studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Lyon at age thirteen in 1853. There he worked in the studio of the etcher/engraver Joseph Vibert (1799-1860) where he not only learned the fundamentals of drawing, but also met and befriended the Realist painter Antoine Vollon (1833-1900). The youthful Roybet soon left Vibert’s studio, however, to pursue independent study at the local museum and in the countryside surrounding Lyon.

His intense focus on painting grew, along with his skill, and in 1863, he sold a large canvas depicting St. Irene the Martyr, thus confirming his belief that painting was his strength. The following year, his father died and Roybet left Lyon for Paris accompanied by his new wife, Amélie Louise Rollion, and their young child. Vollon had moved to the capital five years earlier, in 1859, and he good-naturedly helped his young friend find a place to live and provided introductions to the Parisian arts community. Roybet made his Salon debut in 1865; in addition, he became a member of the Société des Aquafortistes and exhibited his etchings along with his paintings at the Salon in the following years.

Roybet’s first public acclaim came in 1866 with the success of a large painting entitled Fou sous Henri III (The Jester of Henri III). The subject is King Henri III’s jester, Chicot (ca. 1540-1591). He was christened Jean-Antoine d’Anglerais in the Gascony region of southwestern France, and before becoming a jester, he served in the military. Although Chicot was a genuine historical figure, Roybet’s choice of this subject was probably based on the 1846 book by Alexandre Dumas, père, La Dame de Monsoreau. Like Roybet’s painting, the book embraces the romance and glamour of Renaissance France—a time when there were cavaliers and swordsmen and jesters, at least in the popular imagination. [ii] The painting is unusual in its close-up emphasis on the figure of Chicot, who is dressed entirely in brilliant red and positioned against an abstract background of green fields and forests. Accompanied by two large dogs, Chicot carries a jester’s staff and sports a gold-trimmed cap with peacock feathers at the front. What is most enigmatic though is that he appears to be talking or laughing with someone that the viewer cannot see; perhaps it is the viewer that he addresses. The composition won an award at the Salon and it was immediately purchased by Napoleon’s niece, Princess Mathilde Bonaparte. Although Emile Zola described Chicot as a “clothed satyr”, he also proclaimed that it was “an honest painting”; in general, the critical response was positive, and Roybet’s reputation as a promising young artist in mid-century Paris was assured. [iii]

His Salon career flourished during the late 1860s, with successful submissions in both 1867 and 1868. This was interrupted by the shifting dynamics of French political intrigue in 1869 with the failure of Emperor Napoleon III’s colonial adventuring in Mexico followed by his ill-fated declaration of war against Prussia in 1870. Like so many artists who had already completed their military service, Roybet left France for Holland during the Franco-Prussian War. This was his first trip to the Lowlands and he was profoundly impressed with the work of Franz Hals as well as Rembrandt and Jacob Jordaens of Antwerp. The contrasting use of light and shadow and a diligent attention to the details of texture would mark Roybet’s work from this point forward.

In 1872, after returning to Paris, Roybet once again set out to explore other parts of the world, this time in Algeria. There he made copious drawings, some of them using a quill pen, of the unfamiliar environments of North Africa. Many of the paintings from this decade reflect his experiences in Algiers, which has led art historians to refer to Roybet occasionally as an Orientalist painter. This is somewhat misleading, however, as the artist also began to paint cavaliers and musketeers during these years. This might be understood as an unexpected response to his foreign travels, but perhaps it reflects an understanding that the subjects may be “exotic” not only by virtue of depicting a distant place, but also a distant point in time. The theme of creating an escape from the ordinary defines both Orientalist and anecdotal genre painting in this context.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Roybet focused on both anecdotal genre paintings and portraiture. He continued to travel to Spain and Italy, studying old masters and absorbing a variety of techniques. Many of his images from this time rely on the popularity of imagined scenes from the seventeenth and eighteenth century France and Spain. Some emphasize the role of art collecting, usually under the guise of Spanish cavaliers admiring artworks within a lushly furnished private home; there is a sense of humor in many of these works, but also an emphasis on the importance of understanding cultural heritage. In The Connoisseur, Roybet takes an even more serious tone in his depiction of an earnest young French cavalier dressed in extravagant lace and velvet and seated at a table full of artworks where he is thoroughly absorbed in examining a stack of etchings and watercolors. This scene belies the more typical costumed melodrama that characterized anecdotal genre paintings in the late nineteenth century.

Likewise, Roybet produced a number of canvases that would have been considered ‘quaint peasants’ in another artist’s hands, but which in fact, portrayed the hardships of poor and working-class people. The Gypsy Woman is one example; although the title might suggest a kind of overblown romanticized image, it is instead a close-up image of a weary, old woman whose tambourine has seen better days and whose clothing is tattered and worn. She sits alone in a stony landscape, head in hand, as a cloud-filled sky threatens rain. In spite of the presumed mystique of gypsy dancers, this woman is presented to viewers as an exhausted figure who has little hope of a dry place to rest, much less a decent meal. In these types of paintings, Roybet demonstrates an affinity for the Realist and Naturalist trends of his time.

The artist also relied heavily on portrait painting, most likely to ensure a decent income for his family. Although the names of the sitters are often unknown today, there are many images that are clearly portraits of specific magistrates, soldiers, and children. In addition, he is reported to have painted contemporary figures in historical costume; it is difficult now to identify which of the many ‘cavaliers’ might have been originally intended as portraits and which are more anonymous genre paintings designed for a general art market. In contrast, several of his society portraits are identifiable, including Madame Olympe Hériot, the wife of a wealthy department store magnate, and the eccentric Count Robert de Montesquiou, aesthete, art collector, poet and perhaps the model for Joris Huysmans’ decadent character, Jean des Esseintes, in the novel À Rebours. Another measure of his professional success can be seen in his residence at rue du Prony 9. The building, which still stands today, is an elegant six-story, Beaux-Arts structure within a block of the Parc Monceau in the prestigious 17th arrondissement of Paris.

Roybet was equally successful in the American art market. His genre scenes sold well not only among the elite such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, but also to an upper-middle-class art market. An undated ink drawing of a cavalier with a drum also suggests that Roybet had established friendly relationships with American artists; the drawing is inscribed “In homage to the great people of America with thanks for the beautiful gesture of their artists.” [iv] Coupled with his portrait work, Roybet seems to have been a prodigiously productive artist.

At some point around 1880, he had begun taking on students, undoubtedly to help with his extensive production of paintings. [v] One of these was Juana Romani (1867-1923) who also worked as a model. It was his Portrait of Juana Romani that facilitated his return to exhibiting regularly at the annual Salon in 1892. [vi] This canvas reveals how much Roybet’s work had evolved over the years. His early fascination with the dramatic lighting of Rembrandt has been transformed into what might be called a Symbolist evocation of mood. The sitter’s face is spotlighted but her expression remains enigmatic, allowing the viewer to imagine any number of possible explanations. The artist’s attention to texture remains but is now freely painted to create the impression of sensuous velvet and lace, but without the meticulous detail.

Roybet’s return to the Salon in 1892 was followed by the submission of Charles le Téméraire entrant à cheval dans l’église de Nesle (Charles le Téméraire entering the Church of Nesle on Horseback) in 1893, for which he received a medal of honor. That same year, he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, and in 1900, an officer of the Legion of Honor.

In his later years, Roybet’s career took an unexpected turn as he devoted his energy to painting religious images at a time when these were not a particularly popular type of subject. One of these religious paintings, Head of John the Baptist, is a case in point. In spite of the grisly subject, Roybet presents the decapitated head of the saint with a circumspect spirituality. This is clearly a Naturalist rendering of death, but there is a subtle suggestion of a halo as well as the glint of gold along the rim of the platter on which the head is placed. It encourages a serious meditation on death without pandering to voyeurism or a taste for violence. Little is known about Roybet’s motivation for painting these religious canvases, and the dates are equally uncertain, but it may be worth considering that World War I raised disturbing questions about humanity’s willingness to tolerate mass murder and the incapacitation of a generation of young men. As a man in his seventies during the war, Roybet cannot have been unaware of these issues.

Roybet died in at home in Paris on April 11, 1920, just one day before his eightieth birthday. The following year, at the Salon of 1921, he was honored with a special exhibition of twenty of his paintings depicting the Passion of Christ. A further tribute to Roybet’s work and career was established in 1926 when one of his students, Consuelo Fould, left her villa and atelier as a legacy to the nation with instructions that it be opened as a museum dedicated to her mentor, Ferdinand Roybet. Today, the Musée Roybet-Fould is part of a complex of historically significant structures in Courbevoie on the west bank of the Seine near the island of the Grand Jatte.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Chimei Museum, Taiwan

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH

Cliveden Estate, Buckinghamshire, UK

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, St Louis, MO

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Mulhouse, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nîmes, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, Canada

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Musée Roybet Fould, Courbevoie, France

Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Argentina

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana

Syracuse University Art Gallery, Syracuse, New York

The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, FL

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

[i] The Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars lasted from 1209-1229. Pope Innocent III had declared Catharism to be heretical and ordered a crusade to destroy this sect. The Cathars believed that the universe consisted of good and evil spirits, a position that was in conflict with mainstream Christian teachings. For an overview of the late medieval period in France, see Lynn Harry Nelson, “The Rise of Popular Heresies” in Lectures in Medieval History, University of Kansas at: http://www.vlib.us/medieval/lectures/heresies.html

[ii] The book is available for free at Project Guternberg at: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/9637. It is also available on Google Books.

[iii] Emile Zola, “Les Réalistes du Salon” L’Evénement, 11 mai 1866.

[iv] Inscribed in the upper right corner of the drawing is the statement: “Hommage au Grand Peuple Américain et remerciments pour le beau geste de ses artistes.” It is signed “F. Roybet” in the lower left corner.

[v] See catalogue entry on Ferdinand Roybet (#69) by Gabriel Weisberg, Breaking the Mold, The Legacy of the Noah L. and Muriel S. Butkin Collection of Nineteenth Century Art (Notre Dame, Indiana: Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame, 2012) 198.

[vi] Juana Romani, who was born Carolina Carlesimo in Velletri, Italy, moved to Paris with her mother in 1877. She studied painting at the Académie Colarossi, one of the few art schools that accepted female students, and worked as a model for a number of noted artists such as Jean-Jacques Henner, Carolus-Duran and the sculptor Alexandre Falguière. She seems to have begun her studies with Roybet in the mid-1880s. Subsequently, she exhibited at the Salon from 1888 to 1904 where her paintings were well received. As is often the case with female artists, Romani remains an enigmatic figure whose work would benefit from further scholarly research.