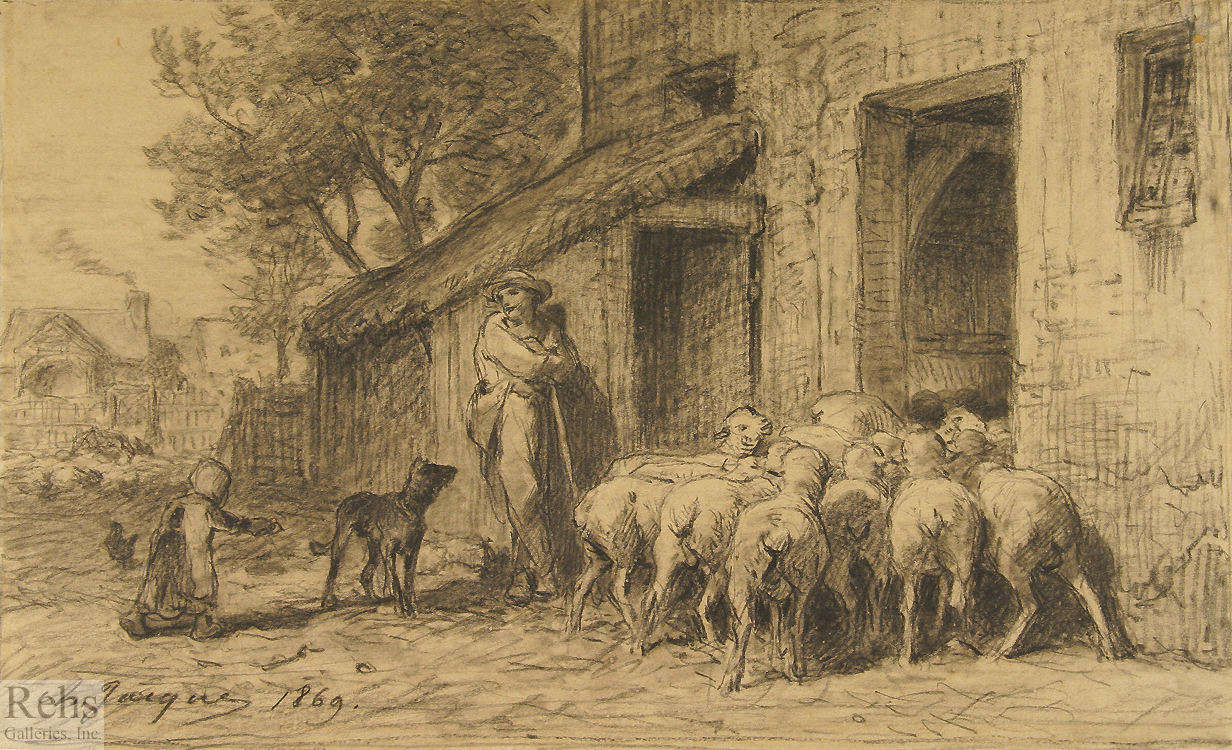

Charles Emile Jacque

(1813 - 1894)

Returning From the Field

Pen & Ink on paper

7 x 11 1/2 inches

Signed and dated 1869

BIOGRAPHY - Charles Emile Jacque (1813 - 1894)

As a member of the Barbizon group, a group of artists whose imagery focused on the depiction of the natural landscape and animals, Charles-Émile Jacque represents the accomplishments of an artist who made his most important mark with his engravings, etchings and lithographs. Throughout his career Jacque submitted regularly to the French salons and also at provincial and international exhibitions in Bordeaux, Lyon, Pau, Châlon-sur-Saône, Munich, London, and even Budapest. His work contributed to the reappraisal of the importance of the print in a time and society dominated by painting.

Charles-Émile Jacque was born May 23rd, 1813 in Paris. At around twelve years of age he was placed in school in the Marais and worked under a notary shortly thereafter. At seventeen he was apprenticed to a cartographer, but having already shown a liking for drawing, his menial task of tracing simple lines from one point to another only caused frustration. Other accounts suggest that he copied lithographs or worked with his uncle who painted chimney fronts. Whatever the case may have been, none of these opportunities gave him proper training in art, in sharp contrast to many other men his age who were already engaged in artistic training at an atelier or at the École des Beaux-Arts. His only true artistic training was around 1840 when he worked in the atelier Suisse, an informal studio which provided models but no instruction, also where Gustave Courbet - who would become a major force behind the Realist movement - worked for a short period of time. Jacque remained largely self-taught and thus self-inspired, which may have been a benefit to his style as he learned to rely on his own methods of representation and not that of a teacher. This lack of extensive artistic training would, however, prohibit him from immediately establishing a career and which may also have affected his choice of medium, as the graphic arts were less expensive and certainly a less prestigious way of launching a career than one in painting.

Apart from a lack of extensive preliminary training, the debut of his artistic career was also hampered by his military service. Often, young men were willing and able to pay for a replacement to serve in their stead, but as his father was not a wealthy man, Jacque was obligated to enlist; a duty that would occupy seven years of his life. During this period he made many sketches of army life and sold small drawings for a franc a piece. He would also later draw from this experience in the military with his many illustrations and caricatures for Parisian journals. Upon completion of his military service in 1838, Jacque quickly began executing his first graphic prints: La Lanterne Magique by Frédéric Soulié, which was inspired by the Napoleonic legend, Vicaire de Wakefield by Oliver Goldsmith, and Chaumière Indienne by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre. Later that year he journeyed to England, drawn to their well-practiced technique of woodcut engraving. During his almost two year period in England he worked as an illustrator for books and journals; producing complete illustrations of The Dance of Death, and a pictorial edition of a Shakespearian play, among many others. Jacque returned to Paris in 1840 with a broader knowledge of printmaking and began a period of intense work in the graphic arts, acting as both an illustrator and caricaturist. At the end of the 1830s, Jacque had become one of the earliest artists to renew the technique of etching, placing him at a definitive position as a forerunner of the etching revival which would come to full fruition beginning in the 1860s with the organization of the Société des Aquafortistes, of which Jacque was a member.

These illustrations and caricatures were the beginning of Jacque’s artistic career and even though he received meager pay, working in printmaking did offer an aspiring artist - without substantial training - a means by which to earn a living and possibly enter the art world. His interest extended beyond the arts to medicine and alongside other artists of the period such as Honoré Daumier and Paul Gavarni, Jacque poked fun at the doctors and their strange and misunderstood medicinal practices, such as bleeding, water therapy and other unusual remedies, in a series of caricatures in the column of Les Malades et Les Médecins in the scathingly satiric journal of Le Charivari, a journal that later came under fire for its mockery of medical and political institutions and personages. These early graphic works of the 1840s include other illustrations, as well, such as the engraved vignettes and satirical lithographs in Militairiana for the Musée Philipon. This work was coming at a time in which illustrated vignettes, such as those Jacque provided, became an integral part of the text, but which also were at risk for coming under fire from the oppressive governmental regimes that, around this time period, had enacted a ban on these types of images.

As his career progressed, Jacque abandoned book illustration and by the mid 1840s began focusing his efforts on producing original etchings which were inspired by the Dutch masters, especially Rembrandt, and which became part of the contribution to the revival of Dutch art. He had first been introduced to these Old Masters early in his career when Louis Cabat, then a porcelain painter who lived next door to Jacque, took him to the Bibliothèque Nationale where they looked at prints by or after the work of Nicolas Poussin, Claude Lorrain, Albrecht Dürer, and Rembrandt van Rijn. However, he became increasingly interested in working on his own subject matter which could be exhibited at the Salon - works influenced by scenes from rural life, including landscapes, peasants, and animals, which he viewed during several journeys through the Seine valley.

Jacque debuted at the Salon of 1844 where he submitted an etched reproduction of a painting by Théodore Rousseau entitled Le Plateau de Belle Croix, Forêt de Fontainebleau (The Plateau of the Belle Croix, Forest of Fontainebleau). In a further extension of artistic diversity, he also worked on his first paintings during that year. In 1845 he submitted to the Salon a portrait copied from Rembrandt. Charles Baudelaire had great praise for the new artist and wrote in Curiosités Esthétiques (quoted from the translated edition Arts in Paris:1845-1862, London: Phaidon Press, 1965, pg. 29)

M. Jacque is a name which will continue, let us hope, to grow greater. M. Jacque’s etching is very bold and he has grasped his subject admirably. There is a directness and a freedom about everything that M. Jacque does upon his copper which reminds one of the old masters. He is known besides to have executed some remarkable reproductions of Rembrandt’s etchings.

His fame growing, he received his first commission from the State in 1846; an engraving of a work by Prudhon for the Church of Murat in le Cantal. Jacque must have been elated over his State commission, as in a letter Jacque notes the importance of commissions and exhibitions when he wrote, “a state commission would be for me the source of my fortune and glory.” (quoted in Pierre-Olivier Fanica, Charles Jacque 1813-1894: Graveur Original et Peintre Animalier, Art Bizon, 1995, pg. 253). He submitted this piece to the Salon of 1847 but it was rejected. Reacting to the growing disapproval of the Salon jury decisions, he banded with other refused artists to create an organization which sought to challenge the Salon; an Association of Free Painters. This was never realized as the Salon of 1848 was open to all in response to the political events of the time that demanded that every piece was accepted. Still, Jacque did not exhibit any w orks at this Salon, despite the guarantee of their acceptance.

In 1849 a cholera epidemic swept through Paris. Jacque, along with his friend Jean-Francois Millet, decided to move his family to Fontainebleau, the safe haven of inspiration for several artists of this period. Here he would find more than just a respite from cholera; he would find inspiration for his artwork as well. He and Millet would become two of the several artists associated with the Barbizon School, a loose association of artists focusing their work on nature and the depiction of peasants and of animals. His earlier work already shows an inclination toward the love of nature, but at Barbizon, surrounded by others seeking the same inspiration, he increasingly focused on painting rustic subjects. Jacque quickly became known as an animalier, or an animal painter. His favorite subjects were sheep, for which he is best known, but he also captured many other farm animals, including cows, horses, domestic fowl and pigs, the latter often forgotten by other artists. Unlike some of the other artists working in Barbizon, the human element in his painting is much less pronounced as he usually focused solely on the depiction of the animal. Rene Menard in The Portfolio of September 1875 asked:

If the word “picturesque” did not exist in the French language one would have to invent it for the works of Charles Jacque: and what is the picturesque if not the sentiment of life in its most familiar form?…Who knows better than he how to paint or draw hens perched on a cart, ducks dabbling in a pond, sheep in search of grass…? His inns, his farms and poultry yards, his village streets, his skirts of forest; his old walls, full of crevices, of stains of damp or crumbling plaster; his barns with cobwebs hanging from their ceilings, charm us precisely because the painter has not recourse to any tricks but merely tells us, in his plastic language, the things that he saw, observed, and studied in the country.

Jacque used this newly discovered inspiration for the series of etchings that he submitted to the Salon of 1850, which earned him a third-class medal (only once in his career would Jacque be recognized above a third-class placement at the Salon).

His experiences at Barbizon also impacted his general interest. He began publishing his etchings in Le Magasin Pittoresque and L’Illustration, but also began submitting articles to agricultural journals such as Le Journal d’Agriculture Pratique, discussing such topics as drainage and irrigation systems for gardens, the raising of animals, among other subjects. His interest in animals took on new dimensions as he began frequenting Le Jardin des Plantes in Paris where he asked Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire for permission to study and to do drawings of animals. Saint-Hilaire was in the process of founding a Société d’Acclimatation, of which Jacque became a fervent member. Not content to draw chickens, Jacque completed a book of his experiences as a chicken farmer at Barbizon entitled Le Poulailler. In 1857 he actually took on the task of selling eggs -- a business venture that not only showed to what point Jacque had interests beyond that of painting, but also that he had wanted to gain a deeper understanding of his subject matter.

He continued exhibiting regularly at the Salons throughout this period and received another third class medal at the Salon of 1861. Regardless of any success at Salon exhibitions, it did not translate into monetary gains during this time, perhaps because Jacque’s agricultural interests were not as successful as anticipated. From 1862-1867 he was plagued by financial problems and was forced to sell much of the property that he owned and abandoned his chicken farming venture. In an attempt to improve his financial situation, he began working feverishly on his prints, editing several series of etchings. He also began executing many paintings after adopting a technique of looser execution, which allowed him to produce work much more quickly, but often at the expense of quality. The detail work that was apparent in much of his previous work was, in some cases, eliminated. He stopped publishing his articles, but did exhibit at the 1863 and 1864 Salon, receiving a third class medal at the latter.

The following years proved to be a busy period for Jacque, as his success brought him recognition and acceptance. Jacque was finally honored with the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 1867 and was also elected to the jury for the 1867 Exposition Universelle. He exhibited a painting, Pastorale (Pastoral), at the Exposition and received another third class medal. He was also on the jury for the 1867 Grand Prix de Rome, a yearly prize given to a young and promising art student who would then have the opportunity to study in Italy for four years. With these accolades, his work began to sell better, and after 1870 he began to earn a good deal of money. He had sacrificed his etchings to his paintings, which began to sell at incredible prices. During the last twenty years of his life he earned two hundred thousand francs per year, an admirable sum for a self-trained artist working primarily in the graphic arts.

In the 1870’s he became involved with a factory at Le Croisic that produced Renaissance and Gothic-style furniture. He restored the older pieces of furniture and then re-fabricated them in the troubadour style after his own designs. He recruited three apprentices to assist him, but later moved the shop to Pau. After 1870 he stopped exhibiting regularly at the Salons and began instead relying more heavily on dealers for the sale of his work, the subject of which remained consistent. In 1881 he began experimenting with watercolors, which he had not done until this point and in 1888 he received Camille Pissarro in his studio, a younger artist who was becoming well-known for his neo-impressionist works. Towards the end of his career his reputation and work earned him a gold medal at the 1889 Exposition Universelle, his final triumph over a series of third place medals at the annual Salons. His work had also crossed over to America where he found great success. As the years passed he watched his colleagues pass away; those other artists who found the same inspiration in nature and at, the village of Barbizon. He was one of the last representatives of the Barbizon School maintaining his enthusiasm and his way of creating close to the twentieth century.

Jacque’s last Salon exhibition was 1894 where he showed Intérieur d’Écurie (Interior of a Stable). He died on May 7th in Paris, 1894.

Several aspects of Charles Jacque’s life and career set him apart from his contemporaries and even his colleagues working at Barbizon. He began his ascension in the art world with little artistic training; successfully transitioned from an illustrator/caricaturist into a position of a respected artist of the “high” arts; was a firm believer in the importance of gaining an intimate knowledge of his subject matter, well beyond simple observation; and most importantly, established himself most prominently not only as a painter, but also an etcher -- contributing to the return of the graphic arts as an important medium of artistic expression. Each of these aspects of Jacque’s career contributes to a further understanding of his placement and importance in nineteenth century art.