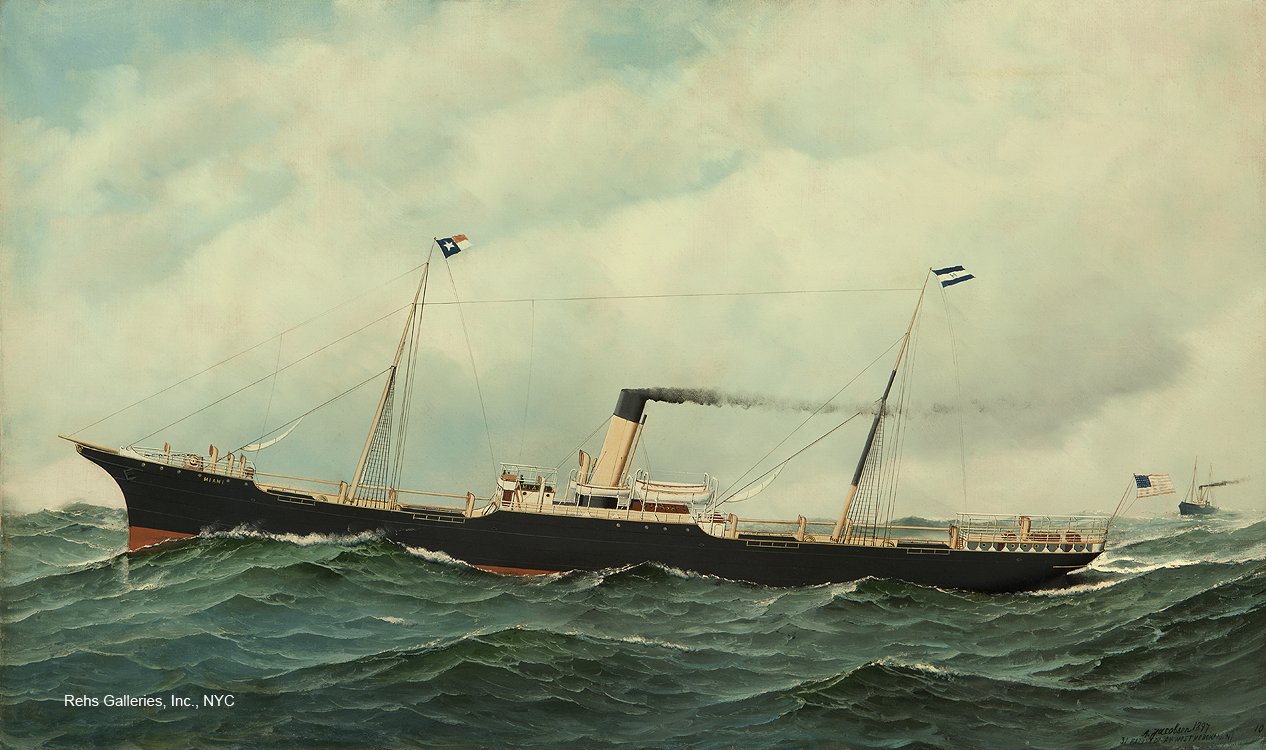

Antonio Jacobsen

(1850 - 1921)

The Miami

Oil on canvas

30 x 50 inches

Framed dimensions:

38 1/2 x 58 1/2 inches

Signed, inscribed and dated 1897

BIOGRAPHY - Antonio Jacobsen (1850 - 1921)

At first glance, Antonio Nicolo Gasparo Jacobsen might seem an unusual name for a Danish child, especially one without Italian heritage. His father, Thomas Jacobsen (1810-1853), was a well-respected violin maker in Copenhagen, proudly naming his son after the three most renowned masters of the craft: Antonio Stradivari, Nicolo Amati, and Gasparo da Salo. Born in Jutland and apprenticed to a local carpenter, Thomas Jacobsen traveled to Copenhagen in 1833 as part of his military service. There, he also continued his studies as a violin maker with Niels Jensen Lund. By 1841, he established his own workshop. In 1842, the internationally celebrated Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, who was performing in Copenhagen, sought out Jacobsen to repair his violin. He was so deeply impressed with Jacobsen’s skill that he suggested the young instrument-maker pursue further education with Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, the most famous violin maker of the period.[i] To that end, Bull wrote Jacobsen a letter of recommendation which garnered him a three-year grant to study in Paris.[ii] Following his tenure with Vuillaume, Jacobsen took a year to travel to other well-known violin workshops in Leipzig, Munich, Nuremberg, and Vienna, returning to Copenhagen in 1847 with a wealth of experience and skill. He enjoyed the patronage of King Frederick VII’s court, with his workshop becoming a center of musical culture in the capital. Antonio Jacobsen was born into this intellectually sophisticated and financially comfortable environment on November 2, 1850.

Young Jacobsen was only three years old when his father died, and the family sold the violin workshop to another instrument maker. It returned to the family, however, when his uncle purchased it several years later. Jacobsen’s childhood was filled with music, and he quickly became an adept musician himself, playing the violin, viola and cello. His interest in painting emerged during his teen years, and he may have studied briefly at the Royal Academy of Design in Copenhagen.[iii] His art education was cut short by a “depression affecting the violin business,” according to his friend Charles Cherry.[iv] The potential painter was then obliged to find employment in a local department store.

With his art education postponed indefinitely, and the family business struggling in tough economic times, Jacobsen soon found himself engaged in his compulsory service in the Danish military. The seeming dearth of prospects for a career outside of the military ultimately led him to take his chances on emigrating to the United States, leaving from Le Havre in the summer of 1883 and arriving in New York on August 21st.[v] Shortly thereafter, he presented a letter of introduction to Leopold Damrosch, the conductor of the New York Philharmonic. Damrosch likely knew of Jacobsen’s family business, as he was himself a renowned violinist with roots in Poland and Germany. As a member of the Philharmonic string section, Jacobsen’s musical skills provided him with sufficient income to cover his living expenses during this time.

Jacobsen’s early years in New York were also marked by his efforts to become a painter. According to an account by his son Alphonse, Jacobsen would go to Battery Park in Manhattan to sketch ships in the harbor. His work soon attracted the attention of a representative of the Marvin Safe Company.[vi] They hired him to paint decorative vignettes on the sides of the company’s safes, including painting a ship on one of the company’s largest safes on the “ground floor room with a large window which exposed him to the gaze of passersby—this in lower Manhattan. A well-dressed man came in and engaged Jacobsen to paint a picture of a ship in which he was interested that was docked in the East River.” [vii] As more people became aware of Jacobsen’s work, his artistic career gradually expanded. By 1876, his name appeared in the New York City Directory as “Jacobsen, Antonio, Artist, 257 Eighth Av.” [viii]

The clientele for Jacobsen’s early paintings centered around the waterfront, where ship captains and crew members would purchase his work for modest prices. As the word spread about his work, however, the artist attracted the attention of shipping company executives and brokers, whose commissions tended to be larger and more lucrative. Typically, Jacobsen would sketch whatever ships were in port. His sketchbooks are full of meticulous details that provided him with an accurate sense of scale for his final compositions. This approach was especially popular with crew members and sea captains because it so accurately represented the ships they piloted. With a growing reputation, Jacobsen became increasingly popular among the leaders of major steamship companies to create paintings documenting their ships’ sophistication and technical prowess. The White Star Line commissioned him to paint every vessel in their fleet. Jacobsen’s client list soon included steamship lines operating along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the US, such as the Old Dominion Line, Fall River Line, and Mallory Line Steamship Company, as well as companies involved primarily in the transatlantic trade, such as the Clyde Steamship Company, Black Ball Line, Anchor Line, Red Star Line, and White Star Line.

The artist’s personal life was also full of new friends in the 1870s. His love of social gatherings and cultural events often brought him into contact with like-minded people, not the least of whom was a young woman from Boston named Mary Melanie Schmidt. Schmidt’s parents were French immigrants from Alsace who had settled in Massachusetts, where her father was a schoolmaster. The precise circumstances of her meeting with Jacobsen remain unknown, but they married on July 6, 1878, at the Church of the Strangers in Greenwich Village.[ix] According to historian Anita Jacobsen (no relation), “Officials of the Fall River Line, in appreciation of the fine work he had done painting every ship of that line, presented the honeymoon couple with a trip to Fall River in the bridal suite of the steamer Bristol.”[x] The couple settled into Jacobsen’s home on the corner of Eighth Avenue and Twenty-third Street in Manhattan, where the painter had been living for several years.

Two years later, they moved to West Hoboken, New Jersey (today Union City), into a gracious three-story Greek Revival house with views of both the Hudson River and the emerging Manhattan skyline. Photographs of the interior reveal that the Jacobsen home was quite contemporary for the 1880s, with Turkish rugs, Eastlake furniture, and even a daringly modern set of bentwood chairs in the dining room.[xi] Even more revealing is a photograph from 1889 showing a chamber group of seven string musicians playing a concert (or rehearsing one?) at Jacobsen’s home. These images provide a clear indication that Jacobsen was not only successful as a painter but that his love of music and performing remained a staple throughout his life. Just a few months after the concert photograph, Mary Jacobsen gave birth to their first child, Helen Amalie, in March 1890. Two sons arrived soon after: Carl Ferdinand in November 1892 and Alphonse Theodore in October 1894.

All of the children accompanied their father on sketching trips over the years. Helen recalls that he “took her on all of his sketching trips until I was seven and had to go to school.”[xiii] In later years, Alphonse shared a memory of going with his father on painting trips to Staten Island with Anita Jacobsen: “He recalled seeing the wooden train sheds at Clifton where many ships were moored off shore” as well as an excursion to Brown’s shipyard at Tottenville to sketch.[xiv] It was Carl Jacobsen, however, who became a serious painter, working with his father as needed and building a career of his own as a commercial artist.

Jacobsen traveled the length and breadth of the New York region with his ever-present sketchbook in hand, generally following the water’s edge. Over the years, he made frequent journeys to Long Island, Newburgh, and Boston. In 1907, he ventured south to the great shipyards at Hampton Roads, Virginia, where he created numerous drawings of steamboats. Despite this roaming, Jacobsen reportedly did not allow it to become all-consuming. His daughter Helen recalled that “he lived happily for many years with his wife, his three children... surrounded by many friends, absorbed in many hobbies — horses, dogs, many birds of bright plumage, and a monkey who knew when the trolley stopped at the corner, a block away, that he was coming home, and made a terrific commotion in joy. He studied, went to concerts, lectures, galleries, and museums, read voraciously, played the violin, and absorbed much good music.”[xv]

Other artists frequently visited the Jacobsen home. A group of marine painters based in the Hoboken area would gather regularly to discuss issues of the day, generally art and music, in the tradition of a weekly salon. James Bard, the oldest of the group, was a prolific marine painter and an important influence on younger painters like Samuel Ward Stanton, a muralist and steamboat expert who was a regular visitor at Jacobsen’s home until his death on the Titanic in 1912. Fred Cozzens, James Buttersworth, Worden Wood, and Albert Bishop —marine painters all— joined in the conversation and camaraderie. In many ways, Mary and Antonio re-created the warmth and sophistication that had characterized Jacobsen’s childhood home in Copenhagen.

This comfortable and genial life would suffer a severe shock in 1909 when Mary died of kidney disease at age fifty-three. Her husband, then fifty-nine years old, and his three teenage children were bereft. He was able to send Helen to college later that year, but could not afford the tuition in 1913 when it was time for his sons to continue their education. Based on his lack of income within a few years of Mary’s death, it would appear that she had managed the family finances. Without her guidance, Jacobsen ultimately had to sell his collection of musical instruments and significant portions of his library to meet his expenses. A final blow came in the form of a fire in 1917 that consumed almost an entire side of his home. Beset by this abundance of problems, Jacobsen reportedly found solace in alcohol more often than was wise.

The entry of the US into World War I also served to damage Jacobsen’s career as the German Navy disrupted transatlantic shipping between Liverpool and New York. A letter from Jacobsen to his friend Edwin Eldredge, dated March 9, 1919, clarified his situation: “I made a good living the past year by painting schooners, but business for shipping here was so bad that all orders stopped in October. It is just as good as I was quite unable to do good work. I found difficulty in concentrating my thots (sic) on work in hand such as taking proportions from Plan or Photo to enlarge on board.”[xvi] Throughout these troubles, Helen remained at home with her father until his death on February 3, 1921. She would live there until 1929, when she married attorney George Chapin.

Jacobsen’s legacy was generally overlooked in the years immediately following his death. Harold S. Sniffen, curator of the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia, began to assemble an important collection of his paintings in the 1930s. A major retrospective exhibition was featured there in 1946, and Jacobsen’s role in the canon of American marine painting was established.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Hoboken Historical Museum, Hoboken, New Jersey

Mariners Museum and Park, Newport New, Virginia

Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, Connecticut

New-York Historical Society Museum, New York

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

South Street Seaport Museum, New York

[i] Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume’s work was recognized with gold medals at the French Industrial Expositions of 1834, 1844 and 1849 as well as at the first International Exposition (the Crystal Palace Exposition) in London in 1851. He was also a major collector of Stradivarius violins, which undoubtedly informed his own design work. For an introduction to Vuillaume’s life and work, as well as further references, see “Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume: notes on his life and work” at https://www.corilon.com/us/library/master-portraits/jean-baptiste-vuillaume-notes-on-his-life-and-work. Ole Bull’s recommendation letter can be seen at: https://tarisio.com/cozio-archive/cozio-carteggio/danish-violin-making-part-2-the-golden-era-1840-1900/

[ii] The grant was funded by the Reiersen Foundation and King Christian VIII. The Reiersen Foundation, which still exists today, was established in 1796 by Niels Lunde Reiersen, who hoped to promote quality design and production in Danish manufacturing.

[iii] According to Harold S. Sniffen’s 1996 article, “Antonio Jacobsen's Painted Ships on Painted Oceans”, in American Art Review, vol. 7: December 1995-January 1996, Jacobsen’s friend Charles Cherry claimed that the artist studied at the University of Copenhagen rather than the Royal Academy. Until further research is done, the question of Jacobsen’s education in the visual arts remains open-ended.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C.

[vi] This story was related to Anita Jacobsen (no relation) by Alphonse Jacobsen and is included in her publication From Sail to Steam: The Story of Antonio Jacobsen, Marine Artist, An Artist’s Chronicle of the Ships that Sailed the Seas from 1870 to 1920 (Staten Island, NY: Manor Publishing Company, 1972).

[vii] Harold S. Sniffen, “Antonio Jacobsen's Painted Ships on Painted Oceans”, American Art Review, vol. 7: December 1995-January 1996.

[viii] Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "New York City directory”, New York Public Library Digital Collections. Retrieved from: http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e71de230-5e73-0134-0c23-00505686a51c

[ix] The Church of the Strangers was founded by Charles Deems (1820-1893) as a non-denominational church in 1868. In 1876, when Antonio and Mary Jacobsen were married there, the church was located at 399 Mercer Street, originally the home of the Mercer Street Presbyterian Church. The building was purchased by Cornelius Vanderbilt for the sole purpose of donating it to Reverend Deems. See: http://www.nycago.org/Organs/NYC/html/ChurchStrangers.html

[x] Anita Jacobsen, From Sail to Steam: The Story of Antonio Jacobsen, Marine Artist, An Artist’s Chronicle of the Ships that Sailed the Seas from 1870 to 1920 (Staten Island, NY: Manor Publishing Company, 1972). Quoted in Harold S. Sniffen, “Antonio Jacobsen's Painted Ships on Painted Oceans”, American Art Review, vol. 7: December 1995-January 1996.

[xi] The Hoboken Historical Museum has several photographs of the Jacobsen’s home in the late nineteenth century as well as a substantial collection of the artist’s paintings. Many of these are accessible online at: https://hoboken.pastperfectonline.com/photo/

[xii] The digital image of the concert in the Jacobsen dining room can be seen at: https://hoboken.pastperfectonline.com/photo/266F8B8A-A9A2-48B0-AEF5-413003160673

[xiii] Harold S. Sniffen, “Antonio Jacobsen's Painted Ships on Painted Oceans”, American Art Review, vol. 7: December 1995-January 1996.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Ibid.