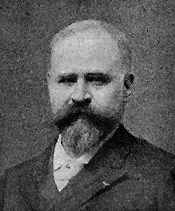

Adrien Moreau

(1843 - 1906)

The Ferry

Oil on canvas

29 x 36 1/2 inches

Framed dimensions:

41 x 48 1/2 inches

Signed

BIOGRAPHY - Adrien Moreau (1843 - 1906)

“The artist M. Adrien Moreau, though still young, has already won his artistic spurs, his canvases being hors concours in the Salon Exhibitions. A pupil of M. Pils, M. Moreau has, like many other followers, emancipated himself from the traditions of his teaching and displayed his own individuality in his works.…M. Moreau is a verification in himself of the artistic axiom that a true artist, when so willed, can give equally good work in landscape as in figure painting.…Like Van Dyck, Mr. Moreau depicts his men as cavaliers, and gives his grandes dames as much refinement as grace. His touch is microscopic in its details, and yet the accessories are always kept subservient to the theme of the story. M. Moreau is an artist to the very tips of his fingers.” [i]

Adrien Moreau was born in Troyes, France on April 18, 1843 into a family with a long heritage of painters, sculptors and designers. Similarly, the city of Troyes had a well preserved architectural heritage, having had the good fortune to have avoided the worst of the warfare over the centuries. Gothic churches dating from as early as the twelfth century and half-timbered housing from the seventeenth century remained intact. The conservation of this architectural heritage was well underway by the mid-nineteenth century. As a child growing up in an artistic family, it seems likely that Moreau would have been introduced to the original stained glass in the Cathedral of Troyes, as well as the gothic and renaissance sculpture in the many remaining medieval churches.

Perhaps as a result of the historical glassmaking tradition in Troyes, Moreau began his artistic career as an apprentice glassmaker. He soon left for Paris, however, to study at the École des Beaux-Arts, probably at some time in the early 1860s. He first worked under Léon Cogniet, but within a year, he began studying with the academic Realist painter Isidore Pils. Because Pils spent 1863-65 in Algeria, it is likely that Moreau worked with him after his return to Paris.

He made his debut at the Paris Salon in 1868 with Puis ce Prophète s’en alla et un lion le rencontra et le tua (Then Shall This Prophet Go and Encounter a Lion which will Kill Him), a religious subject which “placed him among the ranks of the greatest painters of contemporary genre” according to the journalist and art critic, Joseph Uzanne. [ii] The following year, his work was again accepted at the Salon, this time a painting of the Roman emperor Nero at the House of the Belluaries (Belluaires were gladiators who specialized in fighting animals.) These early subjects seem to have been traditional in context, albeit a bit gruesome.

Genuine horror presented itself shortly after the end of the 1869 Salon when Emperor Napoleon III’s declared war against Prussia. Although the Prussian Army defeated the French in relatively short order, the occupation of France that ensued was fiercely resisted by the people of Paris. By early 1871, France was engaged in a civil war as Paris refused to accept Prussian occupation and proclaimed itself to be an independent commune distinct from the rest of France. Battles broke out in the city as the Communards barricaded the streets and fought a guerrilla war against both the invaders and their more compliant countrymen. Like many artists, Moreau remained in Paris, but his studio was destroyed by an explosion in 1871. The hardship of the Commune months was significant; citizens were reduced to eating whatever was at hand while dodging incoming artillery fire from the opposition. By the time it was over, Paris was in ruins and the transportation and communication systems of France were destroyed. The provinces of Alsace and Lorraine were lost to Prussia and the German army would occupy France until the nation paid off a very large war debt for having initiated the conflict in the first place. (Napoleon III and his family fled to London.) [iii]

Moreau began exhibiting at the Salon again in 1873 where he showed the painting, Concert d’Amateurs dans un Atelier d’Artiste (Amateur Concert in an Artist’s Atelier). This work marked a change in subject. As Clara H. Stranahan described this work, it belonged to a “class of historical genre, which he, however, paints with a humorous as well as skillful touch.” [iv] Stranahan doesn’t mention what she found humorous about this canvas, but it might be noted that the “artist’s atelier” depicted here is extraordinarily sumptuous and grand. This painting marked the beginning of a very successful career for Moreau.

Collectors from across the globe vied for Moreau’s work and many of his important paintings were acquired by wealthy Americans of the time. These works were well received by critics as well and many were reproduced in important art history books of the period. One of his anecdotal genre paintings, Un Minuet (The Minuet), was reproduced in an American publication, Famous Paintings of the World by Lew and Giudicelli. The authors wrote glowingly of the work.

In a most delicious series of paintings, Adrien Moreau has given us a charming idea of the luxurious life of the French nobility of the sixteenth century. He depicts the pleasures of an idle class, it is true; but idleness and amusement were the privileges of the wealthy and the great of the period from which he has chosen his subjects.…At the same time a proper subordination of mere accessories to the central interest of the picture is carefully maintained. In this festive scene we hardly know whether to admire most of the faces, so full of expression appropriate to the merry occasion; the figures inimitably graceful in action or in repose; or the lovely woodland setting, in which is framed this picture of an aristocratic holiday. The artist fancies persons of quality for the peopling of his canvases, and makes his men gallant cavaliers, and gives to his grandes dames, or great ladies, as much refinement as grace. He is so careful a student of the times he depicts, that we may know that the customs and costumes are precisely what they really were in these courtier days of France. [v]

The fascination for seventeenth and eighteenth century imagery first became popular during the Second Empire (1852-1870), partly in response to the poor quality of industrially manufactured products. Art critics like Edmond de Goncourt actively promoted the elegant style of the 1700s, and simultaneously celebrated the pre-Revolutionary epoch of Louis XV and Louis XVI. As is often true of nostalgic fashions, the advocates conveniently overlook the less than desirable elements of their chosen time periods, and the Rococo Revival was no exception.

Moreau’s oeuvre is especially intriguing, however, because he continues to experiment in a number of different stylistic vocabularies and techniques. As the authors of Famous Paintings noted, “One thing is true of him that can be said of very few artists – he is equally at home in landscape and figure painting; and he bestows equal care on the portrayal of each, neither being disregarded in favor of the other.” [vi] Moreau’s work goes beyond a distinction between landscape and figure painting, however. He works not only in the Rococo Revival style, but also in a clearly Impressionist style (often combined with Naturalism), and in what might be called a Troubadour Style.

Although the Troubadour Style paintings are often intermingled with the Rococo Revival images, there is, in fact, a distinct portion of Moreau’s work that is characterized not by eighteenth century costumes and settings, but by a medieval historical context. A painting such as Les joyeux drilles (The Happy Girls) depicts a group of men (including a monk) clad in a variety of medieval costumes wandering down a cobblestone street as the women laugh at their public drunkenness. In the background is a gothic cathedral, and nearby, half-timbered houses loom over a stone staircase. Likewise, in Le Marriage (The Wedding), the figures wear late gothic clothing as they stroll through a forest led by a bagpiper and a jester. These types of compositions can only be based on Moreau’s experience of his hometown, Troyes. The half-timbered houses provide the visual evidence and the church in the background may well be the Eglise Saint-Jean-au-Marché in the center of town. The city of Troyes was an active center of twelfth-century troubadour culture, and the young Moreau may well have studied the works of Chrétien de Troyes, the city’s most famous poet and troubadour. As a poet at the court of the Count of Champagne, Chrétien de Troyes was one of the first to write about King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table; he has long been credited with transforming the folk tales of Celtic Britain into the elegant and compelling poetry that continues to enchant readers today. [vii]

At the 1876 Salon, Moreau exhibited one of these medievalist paintings, Une kermesse au moyen age (County Fair in the Middle Ages) as well as a work that demonstrated his increasingly Naturalistic approach, Le repos à la ferme (Taking a break at the farm). Le repos garnered Moreau his first official Salon recognition, a silver medal. During this time, he was living at rue Bergère 7 in the ninth arrondissement of Paris. This neighborhood, just north of Les Halles in Moreau’s lifetime, was a working-class area, which suggests that he was making a decent living as an artist. [viii]

In 1884, the artist combined his Naturalist approach with his Rococo Revival subject matter in Le Bac (The Ferry), his submission for that year’s Salon. As the artist himself described it: “I thought of painting that subject in order to present a cross-section of all the social classes of the 17th century, noblemen, soldiers, peasants, and beggars; at that time there existed few bridges, so to cross from one bank to another it was necessary to take the ferry. My study for the landscape was made on the banks of the Seine, close to the Forest of Fontainebleau.” [ix] Interestingly, the figures seem as if they are inspired by nineteenth century France, despite his stated objective of wanting to portray a scene from the seventeenth century. Moreau’s interest in depicting a cross-section of the social strata firmly places him within the mindset of the nineteenth century artist struggling with social issues of class and stratification.

His occasional rural images reinforce this aspect of Moreau’s work. A painting such as Paysanne aux vaches à la mare (Peasant Girl with Cows at a Watering Hole) offers a sympathetic portrayal of rural life, as does A Battle of Wills, which depicts a young cowherd struggling with her recalcitrant cow. These paintings suggest the influence of Julien Dupré, one of the leading figures in this type of agrarian subject.

Moreau’s work was increasingly popular in both Europe and the United States. He exhibited at the annual Salon consistently; and at the Exposition Universelle of 1889 and 1900, where he earned a second-class medal each time. In 1892, his lifelong contribution to French art and culture was recognized when he became a Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Moreau’s painting was evolving into an ever more Impressionistic style. Paintings of women posed in landscapes, such as L’Attente (Waiting) or Sur la falaise (On the Cliff), not only echo the compositional strategies of Claude Monet in the 1880s, but also the freely brushed surfaces of the Impressionist painters in general. These late paintings also seem to be more contemplative than many of his earlier works, with the figures often wrapt in thought as they gaze into a nearby landscape.

During his lifetime, the artist also received commissions to illustrate several books, including many reprinted works by French literary masters such as Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, Alphonse Daudet and Voltaire. In 1893, Moreau illustrated Voltaire’s Candide, and, in 1899, Le Secret de Saint Louis by E. Moreau. The illustrations were done as both watercolors and drawings. Ultimately, Moreau would write his own book on the history of his family, entitled Les Moreau and published in 1893.

As an active member of the Salon, he continued to live and work in Paris until his death on February 22, 1906.

Selected Museums

Musée d’Art, d’Archéologie et de Sciences Naturelles, Troyes

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Carcassonne, France

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes, France

Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Paris

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

[i] H.W.S., “Sous La Feuille” (Under the Greenwood), The Magazine of Art Illustrated (Vol. 3), 1880, 301.

[ii] Joseph Uzanne, Figures Contemporains Tirée de l’Album Mariani, vol. 8 (Paris: Libraire Henri Floury, 1903).

[iii] There are many books and articles on the subject of the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune, but one of the best in English is Jean Vautrin’s The Voice of the People (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, Phoenix House, 2002), Translated by John Howe. Originally published as Le cri du peuple (Paris: Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, 1999).

[iv] C.H. Stranahan, A History of French Painting (New York: Scribner’s & Sons, 1888) 347.

[v] General Lew Wallace and Henri Giudicelli, Famous Paintings of the World (New York: Fine Art Publishing Company, 1894) 169.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] The works of Chrétien de Troyes can be found on Project Gutenberg, and translated into English at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/831/831-h/831-h.htm

[viii] See Salon entries #1499, Le repos à la ferme and #1500, Une kermess au moyen age in Explication des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, architecture, gravure et lithographie des artistes vivants. (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1876) 186.

[ix] See Eric Zafran, French Salon Paintings from Southern Collections (Atlanta: The High Museum of Art, 1982) 150.