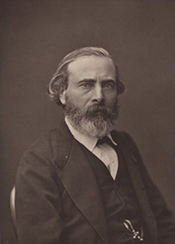

BIOGRAPHY - Pierre Edouard Frere (1819 - 1886)

The finest characteristic of modern art is its sympathy.

- Pierre-Édouard Frère, quoted in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, November, 1871

Pierre-Édouard Frère was a Realist painter who became the leader of the “sympathetic art” movement in France, a vein of Realism which sensitively portrayed the lower classes with dignity and charm, glorifying the simplicity of their lives and their work. While many Realists focused on the gritty spectacles of the streets of Paris, Frère became especially known for his sympathetic portraits of women, and especially young children, completing daily household chores and other domestic activities. This form of art had its origins in the eighteenth century French painting by such artists as Jean-Siméon Chardin and the Le Nain brothers who, in turn, were inspired by the seventeenth century Dutch artists.

This interest in the lower classes was not unique to Frère, as many other artists were also tackling the issue of poverty that had become a major social issue in France. The class divisions in France were too severe not to take notice of the street beggars, the young children in rags, or, in the countryside, the gleaners scavenging for leftovers in the field, as portrayed by Jules Breton and François Millet, among many others. Frère was a strong advocate for the depiction of ordinary people and simplicity in the manner they were portrayed. He harangued the artists who were his contemporaries, who did not feel the same, and who ventured into the fantastic realms outside of that of daily life. His representations of the poor did not necessarily mean to solicit pity, but to portray his subjects with a sense of sincerity and simplicity; he was quoted as saying “Here is poverty, unconscious and beautiful.” (Harper’s, pg. 802) Throughout his career he would encourage others to see beauty in the underprivileged classes, while simultaneously carving out a niche for himself with other sympathizers who became collectors of this sentimental art.

Pierre-Édouard Frère was born on January 10, 1819 in Paris to a father who was a music publisher; Édouard was the younger brother of the Orientalist painter Charles-Théodore Frère. In 1836 Édouard entered the École des Beaux-Arts, at just seventeen, and began studying under the well-established academic painter Paul Delaroche, whose studio boasted many students who would later become very well known such as – besides Frère – Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Albert Boime, in The Academy and French Painting in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Phaidon Publishers, Inc., 1971), wrote that “The studio of Delaroche was perhaps the most competitive of the July Monarchy ateliers….In this atmosphere only the obdurate could survive, and these often outlasted men of superior talent.” (pg. 56) Before beginning his career at the Salon Frère had already executed a number of works and established a modest career for himself, but for those artists seeking widespread acclaim, the main outlet was the Parisian Salons.

Frère debuted at the Salon of 1842 with Mendiants de Dunkerque (Beggars of Dunkerque) and Le Petit Paresseux (The Lazy Young Boy). The following year he exhibited Le Petit Gourmand (The Little Glutton), before putting his Salon career on a five-year hiatus, only to emerge again at the Revolutionary Salon of 1848. During these intervening years he may have been concentrating on establishing contacts in order to begin a career in illustration since between 1844 and 1863 he executed several small drawings for texts such as Veillées Littéraires Illustrées by P. Bry (1848), and later illustrated Les Trois Mousquetaires by Alexandre Dumas, Les Contes de Noël by Charles Dickens, and Le Fils du Diable by Paul Féval, among many others (Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Dictionnaire de l’Estampe en France : 1830-1950, Paris: Flammarion, 1985, pg. 123). Even in these early illustrations Frère already showed a tendency towards depicting modern day people with a sentiment of sincerity, rather than recalling past figures, the former being a key interest of the Realist movement; to depict the current realities.

While many of the Realists thrived on the vibrant life in Paris, Frère grew weary of it, and in roughly 1847 moved his family to Écouen, a small village about eight miles from Paris, remaining there the rest of his life. C.H. Stranahan in A History of French Painting (New York: Scribner’s & Sons, 1888, pg. 393) wrote of Écouen, that:

In the quiet of this village where at his coming the humble inhabitants, it is said, often share with him their frugal meal, he painted its simple scenes with a touch of feeling that converted the mechanical skill perfected under Delaroche into works of a charm that led Parisian dealers to seek him out. There, eight miles from Paris, he lived forty years; and there his attractive character and the popularity of his art drew around him a colony of artists and pupils. To them with their families his house was opened two evenings in the week, besides the regular Sunday night ball of French custom.

Frère became a well-known figure in this small village, bringing the children into his studio to use them as his models, often several at a time. Instead of staying in Paris, like his contemporaries, he traveled “…about the by-ways of France, dressed in farmer’s gray, chatting in barn-yards and hay-fields with peasants, getting into their good graces, and delighting them with his bonhomie and his pretty pictures.” (Harpers, pg. 807) In immersing himself in the people whom he was depicting, his art was given this unique and appealing sense of the truthfulness.

Frère’s relocation to Écouen also began a commitment to painting children that would continue throughout his career. Many of these scenes depicted children helping with the housework, taking care of their siblings, and many other activities that were to the benefit of the family. This served an almost didactic message since it was thought that (Gabriel P. Weisberg, The Realist Tradition: French Painting and Drawing 1830-1900, ex. cat., Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1980, pg. 96):

If the poor and the middle class followed these examples-if they instilled in their own children a knowledge of ethical traditions-then the children would develop into leaders who knowledge and respect for past traditions and customs were assured.…[these pictures] reinforced democratic principles, presenting amusing didactic lessons that idealized members of a community or revealed the family’s role in training young children.

From Écouen, he continued to exhibit at the Parisian Salons. In 1850/51, dubbed the Realist Salon because of the large amount of Realist works included, he was given his first medal, a third-class medal, for his Intérieur, étude (Interior, study), La Lecture (The Lecture), and Le Fumeur (The Smoker), among other works. At the following Salon he was given further recompense, earning a second-class medal. After his showing at the Exposition Universelle of 1855, where he received a third-class medal, he was named Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur.

The year 1855 was important for yet another reason: John Ruskin, a major English art critic who influenced taste and culture in England, took a strong liking to Frère’s images of young children and wrote about them in 1855, comparing “…his coloring to Rembrandt’s and pronounced him to combing ‘the depth of Wordsworth, the grace of Reynolds, and the holiness of Angelico.’ ” (Stranahan, pg. 393) The artistic links between England and France were strong, and many French artists found eager patrons in English collectors. With the support of such a major critic and prolific writer such as Ruskin, Frère’s success in England was almost guaranteed. Further, he became an influential figure to artists in England, since (Howard D. Rodée, “France and England: Some Mid-Victorian Views of One Another’s Painting, Gazette des Beaux-Arts (91), 1978, pg. 40):

Frère’s view of rural life was perfectly in tune with prevailing sentiment, which saw the peasant not only as a noble repository of old-fashioned virtues, but, increasingly, as a patiently suffering and tragic figure. Throughout the next decade the works of numerous English artists were said to resemble Frère…

Soon many of his works were made into reproductions and his images disseminated to the masses. From 1868 to 1885 Frère regularly exhibited his work annually at the Royal Academy, further solidifying the English’s desire to procure his work.

Besides England, Frère’s works were also very popular with American audiences. An article written in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in November 1871 described, in thirteen pages, the art of Édouard Frère and “sympathetic art” in France. Both American and English audiences were drawn to his sincere and subtle views of everyday people, and especially children. Their intimate format – many of his works were small in dimensions – made them perfect for display in a home.

By the 1860s, Frère had become a guiding light to a number of students in Écouen, establishing a veritable artistic colony around this master of the sympathetic. Other painters who gathered around Frère in Ecouen included Paul Seignac, Théophile Duverger, August Schenck, George Todd, Michel Arnoux, Joseph Aufray, Pauline Bourges, André Dargelas, Paul Soyer, Luigi Chialiva, Léon Dansaert, and Henry Bacon. One of his students, who would follow his example, was George H. Boughton, an American who eventually settled in London. Frère promoted his students’ work to art dealers and also maintained relationships with them throughout their career, often visiting them after they had settled in either Paris or London. (The Realist Tradition, pg. 213)

During the following two decade Frère continued to be a major contributor to the annual Salons, exhibiting the same theme in each Salon. Frère partook in one final Salon in 1886, exhibiting, Scène d’Intérieur (Interior Scene) and Le Frère Ainé (The Oldest Brother). He died in Écouen on May 20th, 1886. His family name and artistic career were sustained by his only child, Charles-Édouard Frère, a genre painter and portraitist. The author of the Harper’s Monthly article must have also fallen under the spell of Frère, since he wrote “In a word, there can be no true art where the poor have not happy homes,” (pg. 802) and in effect summing up the issues surrounding Frère and the production of his art.

Pierre-Édouard Frère reacted to the growing concern over the lower classes by depicting them not as products of a society which had rejected them, as many artists had portrayed them, but rather showed them partaking in their daily activities that at this point in history, were beginning to vanish. Frère’s work provides a record of times past, an idealized version of the difficult life faced by the lower classes of the period. Frère’s sympathetic art seems less concerned with social propaganda than do many other Realist counterparts and more concerned with finding charm in the daily existence of people who had less than others.