Born in Paris on 11 November1860, Maurice Levis was an accomplished landscape and genre painter for nearly sixty years. His career spanned not only the early years of modernism, but also the twentieth century developments of cubism and surrealism. Levis’ artistic education began in the late1870s at the Académie Julian where he studied with Jules Lefebvre. He also studied with Henri Harpignies and with Pierre Billet, a painter of rural genre scenes that were often set in Normandy and Brittany.

Levis’ choice of instructors reveals the multiplicity of artistic paths available to a young painter in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Jules Lefebvre was an academically trained portrait painter, who seems to have had a gift for teaching. On the other hand, Harpignies aligned himself with the innovative Barbizon School, traveling to Italy with Corot in 1861; and Pierre Billet, a largely forgotten artist today, was a follower of the renowned “peasant painter”, Jules Breton. The young Levis was thus educated in both the traditional and the pioneering trends of his day.

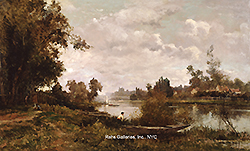

In 1888, he became a member of the Salon des Artistes Français in Paris. Fisherman by a River, dating from that same year, offers a synopsis of the painter’s development at that moment early in his career. At first glance, it is clear that Levis has incorporated many elements from Harpignies’ landscape paintings such as the classical composition of a pathway leading into the distance with a single vanishing point on the horizon. However, the distinctly visible brushwork is pure Impressionism as is the emphasis on brilliant color and light. Like Monet’s depictions of the Seine at Argenteuil from the mid-1870s, Levis’ painting is defined by the use of unadulterated colors laid adjacent to each other on the canvas rather than mixed on the palette. Also significant is his use of scumbled paint and quick stenographic brushwork. What distinguishes this painting from a typical Impressionist landscape is the presence of the blue-jacketed boy who crouches in the reeds with his fishing pole. By including this slightly sentimental figure, Levis harks back to the genre traditions of a painter like Billet or Breton—or perhaps even William Bouguereau whose work he certainly would have known from the Académie Julian as well as the Salon exhibitions.

As his career evolved, Levis seems to have traveled throughout France, and possibly to Africa as well. A painting such as Old Bridge in Mende suggests that he visited Sierra Leone, and Biskra clearly depicts the Algerian town of that name. Other images, Dijibouti and Arab Coppersmith’s Workshop in Constantine for example, are less specific and could easily have been created from photographs of the time. By the late nineteenth-century, it would have been fairly common for artists to use photographs as visual reminders of a particular scene or composition. Figures as diverse as Degas and Gerome made use of this new technology.

Regardless of occasional trips to foreign countries, the majority of Levis’ work depicts the northern provinces of Normandy and Brittany. Beginning in the 1860s, two decades before the arrival of Paul Gauguin, artists had congregated at Pont-Aven in Brittany to paint the dramatic coastal scenes and the local customs (and costumes) of the people. Levis was fascinated not only by the impressive topography here, but also by the medieval château de Josselin, which was then being restored by Jules de la Morandière, a student of Viollet-le-duc, the influential preservation architect of French Gothic buildings. Levis painted the castle repeatedly, sometimes illustrating it as a moody ruin beside the river, and sometimes merely as a part of the contemporary landscape. In addition, he captured the Breton villagers going about their daily chores; women washing clothes at the river, fishing boats setting sail, and farmers tending livestock.

As he grew older, Levis’ paintings became increasingly contemplative. The Seine at Vernon from 1926 is a case in point. Unlike the bright energy of the 1880s and 1890s, this work seems almost elegiac. The silvery atmosphere is reminiscent of Corot’s late works and the composition remains traditional, but the mood is somber, and the barely visible people wear clothing from an earlier era. It is tempting to wonder if Levis was creating a modern form of memento mori, a remembrance of a time before the devastation and violation that World War I brought to this part of France.

Throughout his career, Levis consistently exhibited his paintings at the annual Salon, although auction records indicate that he also sold his work through the growing number of commercial galleries in Paris and London. He also found success with private American collectors whose desire for French landscape painting seemed insatiable. In 1895, he received a Medal of Distinction at the Salon; and in 1896, he received a Third Place medal. It was not until 1927, at the age of 66, that his work was acknowledged with a Gold Medal. Maurice Levis died in 1940 at age 80.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.