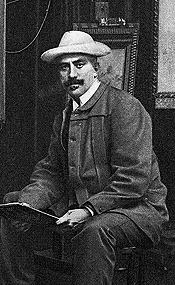

BIOGRAPHY - Jean Beraud (1849 - 1935)

Béraud is a perfect Parisian, not only by birth but by sentiment and art, in the exercise of which he paints the most characteristic Parisian types.…Béraud is not only a perfect Parisian, but he is one who appreciates and can depict Parisian life in its boulevards, cafes, and gardens.

Henry Bacon, “Glimpses of Parisian Art,” Scribner’s Monthly, December 1880, pg. 424-425

Working during La Belle Époque, Jean Béraud was a skilled documenter of Parisian daily life, which by then had become a spectacle of display. While his Impressionist contemporaries were moving out into the country to study the changing effects of the landscape during the late nineteenth century, Béraud remained rooted in Paris, studying the city life and its people. After Baron Haussmann’s reorganization and expansion of the Parisian boulevards during the mid-century, which created the Paris recognizable today, the great expanses of space constructed encouraged people to mill about the city, bringing every member of society out from inside their homes. The life of Paris was now found along the boulevards. No longer were residents traveling in a labyrinthine maze of small, medieval streets. Now fashionably dressed men and women spent their afternoons walking through the park, or strolled along the fashionable boulevards where they could now window shop and indulge their senses. Cafes became major gathering places for both the upper echelon of society and the modern artists seeking refuge from this display of pomp. Béraud had ample subject matter since Paris had become a world of “flaneurs,” or an idle stroller, and the leisurely activity of aimless wandering became a hobby for the most cultured of individuals. He began to document these, and many other images, during his prolific career.

Jean Béraud was born December 31, 1849 in St. Petersburg to French parents. His father, also named Jean, was a gifted sculptor but died when Jean was just four years old. After his death, Jean and his mother moved to Paris where he completed his studies at the Lycée Bonaparte, alongside a fellow future artist, Edouard Détaille. After finishing his obligatory schooling, he studied law. This was before the confusion of the Franco-Prussian war began, after which point he decided to turn to painting. Thus, in 1872, he began his first artistic studies in the atelier of Léon Bonnat, where he stayed for two years.

The atelier was home to many artists who would become well-established in the course of their careers, among them Gustave Caillebotte, Alfred Roll, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Bonnat’s atelier was in the tradition of the École des Beaux-Arts, from which many artists of the period began to deviate because of the École’s strong restrictions placed on more modern art movements. Many times artists would begin their studies in an established atelier, only to follow a different stylistic path to their success. Béraud was no different, since he was quickly enticed by the freedom offered to him by Impressionism, the style which he loosely followed from roughly 1875 to 1900. He looked up to both Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas.

Béraud was described with only the most glowing remarks. He was a “gallant man…always punctilious in his actions…His behavior was always guided by the highest precepts of honor and taste.” (quoted in Patrick Offenstadt’s Jean Béraud: The Belle Epoque: A Dream of Times Gone By, Cologne: Taschen, 1999, pg. 16) Others said that “In a few brief remarks, he could demonstrate a gift for incisive, caustic observation, which you would hardly have suspected from his paintings. As an artist, he was devoid of vanity. He put aside compliments with brusque, smiling modest.” (Offenstadt, pg. 17)

He began his career as a portrait painter, marginally influenced by his master Bonnat, but later focused on facets of daily life along the Parisian boulevards, imagery that found a wide audience at the time. His paintings did not rely simply on the fashionable bourgeois, but also depicted everyday mundane activities; children leaving school, a man leaving his apartment, men and women struggling against the wind – every contemporary theme was now available to him. To capture the essence of this activity, Béraud established his studio in a cab, therefore allowing him to watch unsuspecting p assers-by, while also main taining a regular stationary studio in Montmartre, and later on the rue Washington. The journalist Henry Bacon reminisced about his experience in Béraud’s studio on wheels (“Glimpses of Parisian Art”, pg. 425):

A cab, with the green blind next the street down, attracted our attention, showing that someone was paying two francs an hour for the privilege of remaining stationary. Presently up went the curtain, and the familiar head of Béraud appeared. At his invitation, we thrust a head into the miniature studio to see his latest picture. His canvas was perched upon the seat in front, his color-box beside him; and with the curtain down on one side to keep out the reflection and shield himself from the prying eyes of the passers-by, he could at ease paint through the opposite window a view of the avenue as a background to a group of figures.

These are the images for which Béraud would be best remembered, and for which he gained his greatest fame. He discussed his views of this kind of art, writing humorously that (quoted in Patrick Offenstadt, Jean Béraud, pg. 10):

You have to vanquish your feelings of artistic modesty so you can work among people who take the most irritating kind of interest in what you are doing. If you cannot overcome your disgust, you will end up locking yourself away in your house, and painting a woman or a still life, like all your colleagues. For some artist, that was all they needed to produce a masterpiece. But I believe that today, we need something different.

Certainly the Belle Époque earned its name for a reason – new artistic styles were being introduced, art nouveau began to decorate theaters, shopping stores, and even metro entrances, and the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900 established France - once again - as an artistic leader. Parisians were riding high on this sense of excitement and change, and Béraud documents how this was manifested in the daily activities of Parisians.

By the 1890s Béraud had interestingly decided to pursue religious themes, but nonetheless infused them with modernity, since he placed his subjects within contemporary settings. His first religious work appeared at the Salon of 1883 where he showed La Prière (The Prayer). While religious scenes at one point had become the antithesis of progressive artistic dictum, “by the end of the century there were so many religious compositions – and painters – that the world of art was flooded with religious sentimentality.” (Gabriel P. Weisberg, “From the Real to the Unreal: Religious Painting and Photography at the Salons of the Third Republic,” Arts Magazine, vol. 60 (4), December 1985, pg. 58) To further explain Béraud’s religious imagery and its uniqueness in comparison with his contemporaries, Weisberg wrote (pg. 61):

But whereas Dagnan [ -Bouveret] kept his participants rooted in historical dress and his models completely anonymous, Béraud had something else in mind. His non-religious figures, those who played subsidiary roles to Christ, were dressed in contemporary garments; these individuals were also very carefully modeled on specific members of the Parisian political world. The audience was able to identify specific societal members in the composition readily, thereby understanding that Béraud was trying to comment on life in France through contemporary allusion. When these paintings were shown, however, the general effect was startling: critics and the public had a difficult time accepting a Christ figure seated amidst contemporary politicians – they could not suspend disbelief.

One of his more controversial works was his 1891 Salon – the Salon for the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts - showing of La Madeleine chez les Pharisiens (Mary Magdalene in the House of the Pharisees) “which brought him immense success with the public, but provoked violent polemics from the critics.” (Patrick Offendstadt, “Le Paris disparu de Jean Béraud”, l’Oeil, no. 380 (March 1987), pg. 36) Again, the issue lay in Parisians difficulty in accepting a biblical figure and scene taking place within a contemporary Parisian café, alongside such contemporary figures as Ernest Renan, a very famous writer whose life of Christ was widely read at the time. The controversy was unsurprising.

Any controversy caused by his works only fueled his public persona. He became a well-known figure traveling in affluent circles, maintaining friendships with Marcel Proust and Armand Dorville, among others, and was also frequently received by the Princess Cheref Ouroussof, the countess of Potocks. He lived in all of the fashionable locations in Paris and often depicted daily life on the Champs-Elysées. Joseph Uzanne wrote of Béraud that “This grand man, supple, elegant, ardent sportsman, lively talker and assiduous fighter, of all of his first representations, is by excellence the same type of cosmopolitan Parisian, and worldly artist.” (quoted in Patrick Offendstadt’s article “Le Paris disparu de Jean Béraud”, pg. 35) Béraud clearly interacted with the same people and traveled in the same circles as those he often represented. At the same time, however, his representations were not limited to this group (Richard Thomson, Burlington Magazine, v. 141 No. 1160 (November 1999), pg. 700):

The range of subjects was quasi encyclopedic; in the 1880s his exhibition subjects included an actor performing for a lavish private soiree, a mental hospital, a left wing political meeting, a seedy café, the gratin leaving the Opera, and prostitutes cooped up in the Saint Lazare prison. Thus he staked his claims as a naturalist, recording the nuances and details of Paris.

Throughout his career, Béraud was an active participant in the annual Salons. He debuted at the Salon of 1875 with Léda (Leda) and a portrait. He earned his first medal at the Salon of 1882 where he exhibited L’Intermède (The Intermediate) and Le Vertige (Vertigo), and followed the next year with another medal, exhibiting La Brasserie (The Brasserie) and La Prière (The Prayer), earning a second-class medal which also placed him “hors concours”, or free to submit at will to the Salons. He was always an active participant at these Salons.

But this was also a challenging time for the annual Parisian Salons. No longer were they respected institutions, but rather one that did not promote modernity strongly enough for many artists. To curtail their overall power, several artists, including Béraud, banded together to form the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, and held their own exhibitions beginning in 1890. His first entry in 1890 was Monte-Carlo (Monte-Carlo). His remaining contributions run the gamut from portraits to religious and Parisian scenes. Béraud exhibited here until 1929 and became vice-president in 1893. Béraud also tackled other media and was a member of the Société des Pastellistes Français showing that he, like other artists of his era, revered the importance of the pastel medium which was then being revived widely.

Béraud was a prolific and active painter, and also exhibited at the Cercle artistique et littéraire, the Cercle des Mirlitons, and at the Société Internationale des Peintres et des Sculpteurs. At the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, he was given a gold medal. He continued to submit work to both local and international Salons. By the end of his fairly illustrious career, he had also become an Officier de la Légion d’Honneur (1894) and a member of the Salon jury, in addition to his other work previously mentioned.

The latter years of his life were plagued by ill health. Prone to depression and physical exhaustion, his commissions became more and more rare after the outbreak of World War I. He began to paint less and his images lacked the vibrancy of his earlier period. Paul Leroi wrote that “M. Jean Béraud started out by painting his contemporaries, a task he performed with taste and wit. Now, however, he is inking deeper and deeper into the morass, having unfortunately taken a wrong turn some years ago.” (quoted in Offenstadt, Jean Béraud, pg. 10) He died in Paris on October 4, 1935. He is now buried in Montparnasse cemetery.

Béraud is best known for his images of Parisian life, documenting the minutest details. But as La Belle Époque came and went, France was thrown into World War I. Times continued to change, but his images of Paris during its end of the century heyday will remain evocations of the glory of a time gone by, and suggest a city of myth that only partially existed in reality.

A catalogue raisonné of Béraud has been published in conjunction with an exhibition held in September to January 2000. Those seeking more information on Jean Béraud should secure The Belle Époque: A Dream of Times Gone by Jean Béraud by Patrick Offenstadt (Taschen-Wildenstein Institute), 1999.