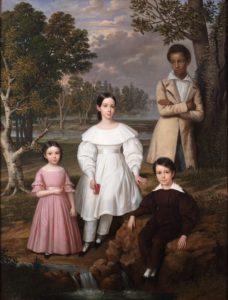

New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art announced the acquisition of an American nineteenth-century group portrait that includes a figure that was previously painted out. The painting was created in 1837 and is likely by Jacques Amans. Amans was a French painter trained in the neoclassical tradition of Jacques Louis David, but he lived in New Orleans from 1837 to 1856 while working mainly as a portraitist. Early on in his New Orleans career, a local banker named Frederick Frey commissioned him to create a portrait of his three children, Elizabeth, Léontine, and Frederick Jr. The painting was donated to the New Orleans Museum of Art in 1972 by the family’s descendants, where it sat in storage until 2005. The museum deaccessioned the work, selling it at Christie’s New York for $6,000 hammer.

The buyer, an antique dealer, saw that the children were not the only ones in the painting. There was a ghost. The brushstrokes indicated that another figure, in the background against the tree, had been painted out of the work. The new owner tried to remove the layer of overpaint concealing this ghost. It was a mixed-race boy that someone took great care to hide. The portrait would not become well-known until it entered Jeremy Simien’s possession. Simien, a Louisiana art collector, first saw the portrait in 2013. He purchased the work in 2021 and had it completely restored. He also hired historian Katy Morlas Shannon to research the Frey family and discover details of this boy’s life. It turns out his name was Bélizaire. He was an enslaved mixed-race boy who, according to Shannon’s research, the Frey family purchased along with his mother when he was six years old. Bélizaire is about fifteen in the portrait and likely worked as the three children’s caretaker. None of the Frey children would survive to adulthood, though. In 1856, the Freys sold Bélizaire to the Evergreen Plantation, nearly thirty miles west of New Orleans in Edgard, Louisiana. Despite his enslaved status, his inclusion in the portrait shows that the Freys considered him an important member of their household. But though he is included, he is still detached from the other children, standing behind them, leaning against a tree, and looking away from the viewer rather than straight ahead. Researchers now estimate Bélizaire was painted out of the portrait during the Jim Crow era.

Before Simien gave the portrait to the Met, Bélizaire and the Frey Children spent about a year being exhibited at the Ogden Museum of Art in New Orleans. Simien remarked, “I had a duty to place it somewhere with the best interpretation, the safest, where it wouldn’t be forgotten again.” The Met’s acquisition of the work is most opportune, as the museum’s American Wing celebrates its centenary this year. But hopefully, Bélizaire’s story and his image’s story can teach a valuable lesson: that he is but one of many. Hopefully, he can represent the unknown thousands intentionally erased or omitted from our stories. Starting in 2020, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the Black Lives Matter protests, people of color received their re-recognition by the Met. In the American Wing, for example, the Met changed the name and description of a George Washington portrait to include the president’s enslaved servant William Lee, also featured in the painting. Though they’re small actions, it’s the falling of small stones that starts an avalanche. With such recognition, Bélizaire helps us develop a more complete understanding of what American art was, is, and can be.