John Stobart

(1929 - 2023)

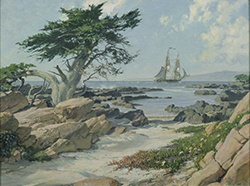

San Francisco, The Gold Rush Harbor by Moonlight in 1851

Oil on canvas

30 x 50 inches

Signed and dated 2009

BIOGRAPHY - John Stobart (1929 - 2023)

John Stobart’s start in life was quite unexpected. His mother died when she was seven months pregnant, making her unborn child’s chance of survival uncertain. Nonetheless, the baby lived, and soon joined his older brother George (1927-2005) and his father in their modest home in Allestree, an attractive village north of the county town of Derby, England. During Stobart’s youth, Derby was a railroad hub as well as home to the Rolls Royce Company, which designed the Merlin aircraft engine for the Spitfire and Hurricane planes made famous in World War II. His father, Lancelot Stobart (1890-1966), was a pharmacist for Boots the Chemist, then and now one of Britain’s most well known drug store companies. In Stobart’s youth, Boots was more of a small department store than what is typically described as a drug store, containing several restaurants, a lending library and clothing in addition to the usual pharmaceutical products. Stobart’s father started out in a small pharmacy in Allestree, but was then promoted to the signature store in central Derby.

The Stobart brothers were very close. Although only eighteen months older than John, George was a willing guide to all the intriguing wonders of the area around their home. They explored the nearby Derbyshire Dales, which offered an abundance of natural features, including many that have since become popular in films of Jane Austen’s novels. They even ventured to Kedleston Hall, home to the aristocratic Curzon family, whose residence in Derbyshire dates back to 1150s. The current hall was commissioned by Sir Nathaniel Curzon in 1756 and was intended to be a “temple of the arts” that would feature the family’s art collection and fine furniture. [i] Matthew Brettingham was the original architect of the project, but he was replaced in 1758 when the young Robert Adam was hired to design the garden buildings and the parkland surrounding the hall. [ii] To the twentieth century Stobart brothers, Kedleston Hall must have seemed like a vision out of a storybook. In later years, John would return often to paint the breathtaking setting and elegant stately home.

Another favorite activity for the brothers was their weekend visits to their housekeeper’s home in Weston Underwood, a hamlet north of Allestree. Auntie Forman, as the housekeeper was called, occasionally took the boys home with her to give their father a break—and simultaneously introduce the brothers to country life. A nearby farm family had daughters about the same age as the boys, and the four of them would go swimming in the brook and help with the farm chores. It opened up yet another world for them.

It was not until 1938, when Stobart was eight years old, that he first met his mother’s family. His father had finally agreed that the boys could take the train to Liverpool on their own. They would transfer at Manchester and be met by their Uncle Ernest in Liverpool, who would then take them to stay at his house. There, they met their Auntie Rosa and many cousins, an event that Stobart recalls as being the first time he felt a sense of belonging to a family.

Meeting his grandmother, who lived in suburban Roby, also marked a turning point in his young life. The tram that stopped at the end of her street traveled directly to the Pier Head in Liverpool. By the time he was twelve, Stobart was allowed to board the tram on his own and get off when he reached the end of the line. His first trip to the docks left him in awe of the vast number, sizes and types of ships that he could see. In talking about that magical day now, he recognizes it as “a life-changing day”.

The happy days in Liverpool and Weston Underwood would soon be interrupted however. Stobart was once again in a port city, this time in Bridlington on the North Sea with the housekeeper Ida, when news of Hitler’s invasion of Poland arrived in early September 1939. Stobart recalls the day vividly: “I was trying to catch a mass of fish in the harbor when suddenly, people came running, saying ‘We’ve declared war’. And then all hell broke loose.” John and George were both enrolled that fall at Derby Grammar School, but they were soon evacuated to Amber Valley Camp to keep them safe from harm.

Located sixty miles north of Derby, Amber Valley Camp was largely rural and very appealing for young boys. Stobart spent his spare time drawing as he had from a young age, and gradually began to expand his repertoire to include the design of three-dimensional objects during breaks from school. At age fourteen, he designed a canoe from the extra wood left on nearby housing sites. It capsized as soon as the passengers took their seats, but Stobart kept working on the design until he had a successful—and seaworthy—vessel. Over the years, his drawing continued to improve, becoming more sophisticated with every project.

By late summer of 1945, Stobart had completed his studies at Derby School and was pleased to learn that his father had met with Frank Hounsell, the head of the Derby College of Art, to inquire about the possibility of his son pursuing a career in art. Hounsell was agreeable, and Stobart was admitted without even being required to take an entrance exam. This was perhaps the first of many “strokes of luck” as Stobart calls them—an unexpected opportunity that would subsequently shape his career as an artist. He began studying that fall with the painter Alfred Bladen (1899-1967). The curriculum at the College was based on the traditional academic program of studying drawing first, then painting, and finally painting from a live model. Stobart was thoroughly enjoying himself; rather than struggling with his studies, he was now in his element. Coursework was supplemented with visits to museums and galleries in Birmingham, and it was there that Stobart was inspired by the work of John Constable. The years at Derby College of Art provided a solid foundation for the young artist’s career, teaching him how to depict the images that most fascinated him, particularly scenes from the era of sailing ships.

About midway through his education at the Derby College of Art, Stobart determined that he would paint Kedleston Hall, the neoclassical estate that he and George had visited as children biking the countryside. After obtaining permission to paint on the grounds, he set to work on a view of the Hall with the parkland surrounding it. It was a particularly memorable day. Stobart tells the story in his own words.

As I worked, I noticed a man with a dog leave the south wing of the residence probably one-quarter mile away. Seeming to be walking towards me, he came up wearing a deer-stalker hat and asked, ‘It’s Stobart, isn’t it?” “Yes, sir,” I replied. “Oh, you’re making a fine job. Ado, you have everything you need?” I told him I had a sandwich and beaker but no water. “Oh,” he said, “right behind you (300 yards) is a faucet in the first bridge abutment. You can’t miss it. I’d like to see that when you’re finished.” I acquiesced, and he went on his way. It was Lord Scarsdale, a charming gentleman.

So I went off, found the water, and returning to my spot, I was stunned by what I saw! A large group of cattle all swishing their tails surrounded my easel. I ran, scattering them, to find my painting lying on the ground, face-up, licked clean! Cleaning the thick green saliva off the canvas and washing it off with turps, I spent another two-and-one half hours repainting. His Lordship would acquire the original. [iii]

Stobart finished his studies at the College of Art in 1950 and left for London to pursue his art education at the Royal Academy Schools that fall. The Derby Education Committee had awarded him a scholarship that would allow him to continue his studies there. He found a boarding house at Earl’s Court, which was a convenient subway ride away from the Royal Academy Schools near Green Park. He lived on the top floor of a Georgian row house that he describes as full of “very nice people” who looked out for him and helped to introduce him to the city. After two years of studying, Stobart left to fulfill his compulsory National Service as a radar specialist with the Royal Air Force. He soon found himself stationed in Dorset not far from Osmington Village where John Constable had not only spent his honeymoon, but also painted several views of Weymouth Bay as well as Osmington itself. Stobart was delighted to find himself walking in the footsteps of an artist whose work he so admired.

By 1955, he was back in London finishing his studies at the Royal Academy Schools.

Not far from the back entrance to the school on Cork Street was the Burlington Arcade, a center for luxury shops and, more importantly, the J. A. Tooth Gallery. Tooth specialized in equestrian paintings, but he and Stobart had become friends when the artist became a regular visitor to the gallery—as the artist recalls, he loved the smell of Tooth’s cigar smoke combined with the mastic varnish used in the gallery. Eventually, Stobart brought Tooth a few of his paintings to review, and on one occasion he left two of them in the gallery overnight. The next day, the RA school’s porter interrupted him during life drawing class to say that Tooth wanted him to come to the gallery immediately. (Interrupting the life drawing class was strictly forbidden, but Tooth had obviously persuaded the porter of the urgency of his request.) Much to Stobart’s surprise, one of Tooth’s clients had taken an interest in his painting of a tugboat on the Thames and wanted to purchase it. That client was John Meadows Marsh, Q.C. of Toronto, who was in town for only a short time; despite the briefness of their encounter, the two men formed a bond that would eventually lead Stobart to Canada and the beginnings of his professional career. Reminiscing about his friendship with Tooth and the propitious arrival of John Meadows Marsh, Stobart describes it as a “miracle”, one of many that he has seen over the years.

During Stobart’s years at school in London, his father had made a major change in his own life, marrying again and moving to Bulawayo in southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). He informed his son of these developments in a letter from Bulawayo, inviting him to visit and sending a ticket for the trip. Stobart took a sabbatical from school and set out for his first ocean voyage. He traveled to Cape Town, South Africa, and then overland to Rhodesia. On his return trip, he took a more northerly route through the Red Sea, the Suez Canal, the Mediterranean Sea and then back to England. In addition to seeing much of Africa and many seas, the voyage provided Stobart with a detailed understanding of how ships function on a daily basis. He returned with a plethora of oil sketches from the numerous ports he had visited on his voyage.

During his time in Africa, it occurred to him that British shipping companies might be interested in paintings that portrayed their ships in exotic port cities such as Dar-es-Salaam or Mombasa. Back in London, he put this idea into action, obtaining a set of plans for the ship Braemar Castle, and one month later, presenting the finished painting of the vessel in the harbor of Mombasa to the Union Castle Line. Within days he had a sale. This strategy would serve Stobart well for many years; he painted for several British and Canadian shipping companies, first on speculation, but soon on commission. By the early 1960s, some of the shipping companies were sending him overseas to paint their ships in specific locations.

During these early years of his career, Stobart also made his first trip to Canada, where he stayed with John Meadows Marsh, Q.C., the collector who had purchased his painting at J. A. Tooth’s Gallery. There he painted a 30 x 50 inch canvas depicting the arrival of the Princess Irene, the first ocean liner passenger ship to visit Toronto via the newly opened St. Lawrence Seaway. [iv] While in Toronto, Stobart also contacted the Maritime Museum in the hope of learning more about sailing ships from earlier eras. Alan Howard, then curator of the museum, was already familiar with the artist’s work and the two men soon became close friends. Howard introduced Stobart to the history of clipper ships and other sailing vessels, and taught him how the intricate rigging of each type of ship was used under variable weather conditions. After four months working with Howard, Stobart had a detailed understanding of the subject. His research in the historic sailing ships also confirmed his own sense that it was time for a new direction in his work; the large cargo vessels of his own day were slowly being transformed into container ships which held little visual interest. Turning to the sailing vessels of earlier centuries gave him more scope for his work.

In 1966 Howard recommended that Stobart make a trip to New York where there were abundant galleries and a much larger art market. What happened next is another of the turns of fortune that Stobart describes as “miracles”. On his train ride down the Hudson, he was joined by a commuter at Irvington-on-Hudson. The man clearly did not want to talk, so Stobart began to review his black & white photographs of the paintings that he wanted to show the art dealers in New York. At that point, his companion took an interest and the men began a conversation about galleries in New York. By the time the train arrived at Grand Central Station, Stobart had recommendations to visit four galleries that might be interested in his work—when he looked at the business card that his traveling companion handed him as they said good-bye, he realized that he had been talking with Donald Holden, the editor of American Artist magazine. This surprising “stroke of luck”—not unlike his meeting with John Meadows Marsh—would introduce Stobart to the New York art world with a recommendation from one of its central figures.

Following Holden’s advice, Stobart headed directly to the Kennedy Galleries on 5th Avenue. [v] The gallerist working that day was interested enough in his work to suggest showing it to Rudy Wunderlich, then the owner of the gallery. Wunderlich, a large man wearing a ten-gallon hat, was equally impressed. Although he specialized in Western art (hence the ten-gallon hat), Wunderlich also dealt in maritime paintings and Stobart’s pieces appealed to him. He asked if Stobart could create twenty-five paintings in time for an exhibition in six months; naturally, the answer was yes.

Stobart remained in New York working on the paintings for the next eight months. With his new focus on historical sailing ships, he sought out photographs of nineteenth century harbors along the East River as the starting point for his twenty-five paintings. His exhibition at Kennedy Galleries opened right on schedule and his career as a maritime painter was securely launched in the US.

Eight months after arriving in New York on the train from Toronto, Stobart returned to London where he continued to develop his knowledge of sailing history as well as his reputation as a maritime painter. Not surprisingly, he found himself drawn to the Thames waterfront but also to the architecture that lined its banks. As maritime scholar Andrew W. German explains “he looked for a way to combine those in a historically engaging way. A survey of sources revealed that, while British ports were well documented by artists in the age of sail, the details of American ports had been ignored by all but a few artists.” [vi] Stobart realized that there was an opportunity to take on the task of painting American ports based on whatever archival etchings, lithographs of photographs were available; and in the late 1960s, he “challenged himself to recreate faithful impressions of specific ports at specific times.” [vii] He initially directed his attention to the waterfront along South Street in New York, often encouraged by Peter Stanford, founder and director of the National Maritime Historical Society and South Street Seaport, which housed abundant historical sources in its museum.

By 1970, Stobart moved to the US, staying with friends in Tarrytown before renting a small house there. Shortly thereafter, he developed a problem with his eyes and was hospitalized briefly. With his typical optimism, however, Stobart explains that this unfortunate event introduced him to a fellow patient named Bob Gregory, a stockbroker, who was curious about the guy painting in the hospital bed next to him. Gregory became a close friend and informal advisor on settling in the US. During Stobart’s transition from London to New York, Gregory asked him to house-sit his 13-bedroom mansion in Long Neck Point, Connecticut during the winter months when he typically lived in warmer locations. Having the security of a rent-free—and quite glamourous—place to live gave Stobart time to get his green card and begin to settle into the arts community in New York City; in particular, the Salmagundi Club in Greenwich Village offered a welcoming place where he could meet a variety of people involved in the arts. During this period, he also began to make regular trips to Mystic Seaport about 35 miles away. The working shipyard there not only provided an opportunity to study the construction of historical vessels, but also the techniques employed by related trades such as barrel-making and rope-making. Stobart described it as a “sensational” education in all of the components of building a sailing ship. Eventually, Stobart would find a house in Darien, Connecticut, where he and his family would live for the next decade.

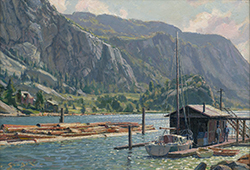

Stobart’s reputation as a maritime painter grew steadily during the 1970s and 1980s. He explored new historical subjects such as whaling ships and also began to paint the harbors of smaller port cities such as Darien. Eventually, he broadened his scope of subjects even further, including the port cities along the great rivers of the US and the Great Lakes. Nineteenth-century riverboats also caught Stobart’s attention and soon became part of his repertoire. [viii] By the late 1980s, he had spent fifteen years creating large and detailed paintings of North American historical sailing ships. It was at this juncture that his friend Bert Wright, a British marine artist, invited Stobart to join him in painting outdoors, following the example of John Constable’s practice of making oil sketches on site. Smaller in scale and more spontaneous than the carefully planned canvases of sailing ships, these plein air paintings have become a mainstay of Stobart’s work since then.

Nature had long served to both inspire and educate Stobart in his work, and his return to plein air painting reminded him of the importance of studying on site. To encourage young artists in this endeavor, he established the Stobart Foundation in 1988. The statement of purpose for the Foundation is very clear. “The Foundation realizes the seminal step for an artist to move from student to professional occurs when each artist learns to use passion and sensitivity to shape the technical skills mastered as a student into a mature and independent visual language recognizable as one’s own. This imperative step is unfortunately most frequently encountered just after leaving the protective environment of the program, and before the artist has a body of work able to be self-supporting in the professional art world. During this time of transition, with the least time and energy available to the fledgling artist to give the required focused attention on this important development, many deserving young artists turn to other methods and opportunities in order to make ends meet.” [ix] To date, the Foundation has provided over 100 fellowships.

Stobart’s plein air work also gave rise to his involvement with the Public Broadcasting System’s Worldscape series in 1992. The premise was that Stobart and some of his fellow artists would demonstrate plein air techniques in the hope of encouraging people to paint landscapes. There were thirteen programs per year, each one lasting two hours. Season one focused on the Caribbean, France, Hawaii and both the east and west coasts of North America; season two included New England and England.

At the same time, Stobart continued to create large canvases depicting sailing ships in the harbors of the world. Occasionally, he would select a specific historical incident as the subject—San Francisco, The Gold Rush Harbor by Moonlight, 1851 is one example. The scene captures the intensity of 781 vessels jockeying for a position in Yerba Buena Cove during the height of the California Gold Rush. The moonlight on the sails and water is both elegant and romantic, but the painting also hints at the absurdity of so many ships crammed together like cars in a parking lot during a holiday sale. In fact, it captures the spirit of the Gold Rush succinctly.

Although the demand for Stobart’s paintings has grown consistently over the decades, he also recognized that limited edition prints of similar scenes would allow more people to collect his work. With that in mind, Stobart developed a series of prints and eventually opened his own gallery in Salem, Massachusetts. [x] As with the paintings, there is a range of subjects from historical harbor scenes to contemporary landscapes and cityscapes. Likewise, Stobart began to publish large format art books featuring his work. A letter from one of the book purchasers revealed just how enduring the appeal of Stobart’s work is. “I just rediscovered your book. It sat on a high shelf for a couple of decades. Today I pulled it down. Looking at the paintings, I realized why I bought it. They are even better than I remember. I also did something today that I didn’t do all those years ago—I read it. That was a huge pleasure in itself.”

Over the years, Stobart was able to purchase several residences that were well suited to his painting. He built a house and gallery on Martha's Vineyard; he had a townhouse on Boston’s Union Wharf in the 1990s and also had a "tree house" on Hilton Head. It was in Boston that he met Anne Fletcher at an “exercise place” in 1984. The story he told is that her yellow dress caught his eye, but the dozen roses he sent her the next day suggests that he was fascinated by more than the color of her dress. The couple were married in 2020 and lived in Westport, Massachusetts.

Stobart continued to paint into his 90s, but he also focused on another publication as well as providing educational opportunities through his Foundation. In a letter to a relative in England, he explained his profound commitment to the work of the Foundation, particularly his belief that setting an example for young artists offers encouragement and wisdom about the process of building a career. “New projects arise out of my special mission to explain my pathway to success, which has been somewhat unbelievable but needs explanation. What I need to leave behind is a pathway to success which would be advantageous, informative, and encouraging to students who find themselves in a similar position to the one I was able to get through. And to demonstrate how they can enjoy every minute of the process. In other words, I hope to build their confidence.” Stobart’s optimism and his faith in the “strokes of luck” that came his way belied the reality that his gift for recognizing opportunity and his curiosity about the world were at least equally important to his long and successful career. John Stobart died on March 2, 2023, at the age of ninety-three.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

American Merchant Marine Museum, Kings Point, New York

Butler Institute of American art, Youngstown, Ohio

Maritime Museum, Bath, England

Maritime Museum of Upper Canada, Toronto

Minnesota Marine Art Museum, Winona, Minnesota

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

Royal Naval College, Greenwich, England

Ventura County Maritime Museum, Oxnard, California

Westervelt-Warner Museum of American Art, Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Notes

[i] Kedleston Hall is today part of the National Trust. A brief description of its history can be found at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/kedleston-hall/features/the-history-of-kedleston-hall.

[ii] See also the National Trust website on the architecture of Kedleston Hall at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/kedleston-hall/features/the-building-of-kedleston-hall.

[iii] John Stobart, John Stobart, a Retrospective, An Artistic Journey from Derby Across the Atlantic (Beverly, MA: Osmington House Publishing, 2015). Exhibition catalogue. 12.

[iv] The St. Lawrence Seaway is a series of locks and canals along the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes that allows the passage of oceangoing ships from the Atlantic to the ports of the Great Lakes. The concept was first proposed in the nineteenth century, but it was not until after World War II that the Canadian government started to develop it seriously. The United States supported the idea, but political wrangling in the Congress meant that Canada undertook the project independently in 1952. By 1954, the US decided to participate. Opening ceremonies were held in 1959 at the first lock on the Seaway at Saint-Lambert, Québec (near Montréal); a short cruise aboard the HMY Britannia was hosted by Queen Elizabeth II and President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

[v] Kennedy Galleries opened in 1874 as Hermann Wunderlich & Co. Edward G. Kennedy took over after Wunderich’s death in 1892, eventually changing the name to Kennedy Galleries in 1912. It remained a center for representational art until it closing in 2005. See The Frick Collection, Center for the History of Collecting: https://research.frick.org/directory/detail/1730

[vi] Andrew W. German, John Stobart, The Grandeur of America’s Age of Sail, (Beverly, MA: Osmington House Publishing, 2009) 17. Exhibition catalogue.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid. German’s book about the American age of sail contains numerous color plates and an extended discussion of Stobart’s art work during his years in North America. For a detailed discussion of the paintings, see 17-21.

[ix] For more information, see The Stobart Foundation at: https://stobartfoundation.org

[x] For more information, see Kensington-Stobart Gallery at: https://kensingtonstobartgallery.com

| AVAILABLE WORKS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||