SEXES

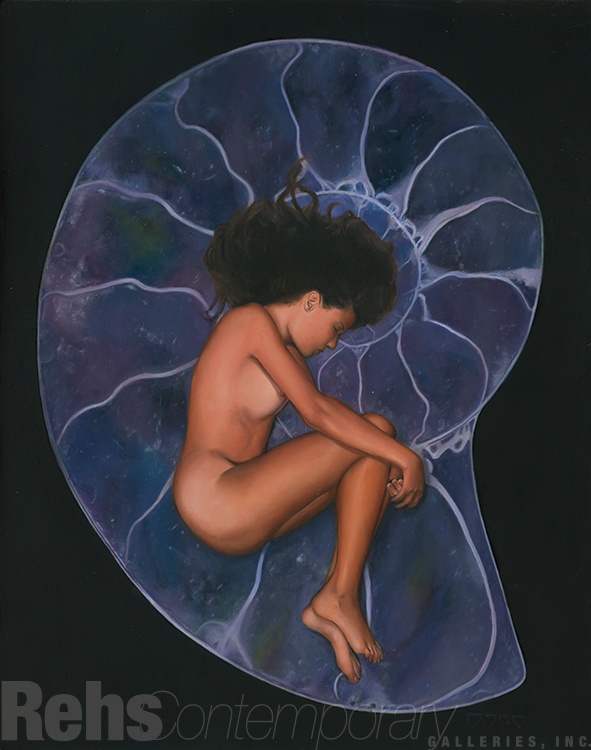

Edward Dillon "Cosmos"

Questions and Answers

By Peter Trippi

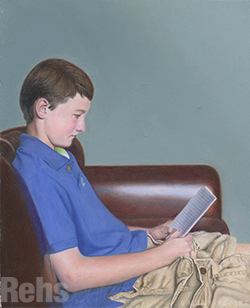

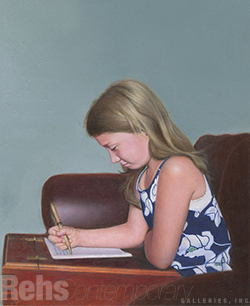

“Third time’s the charm,” they say, so there is extra cause for celebration as Rehs Contemporary opens its third exhibition of paintings and drawings created by the instructors, alumni, and apprentices of the Ani Art Academies. This is the international network of ateliers established by the artist, philanthropist Tim Reynolds and artist, educator Anthony J. Waichulis - both for whom rigorous skill in draftsmanship will always remain paramount. Indeed, the black-and-white works made by Ani artists are often as visually compelling as the color images of their counterparts at other academies.

Building upon the curriculum that prevailed in the 19th century, and which has, almost by accident, come down to us through a handful of fearless practitioners, Waichulis enhances students’ superb training in draftsmanship with the other building blocks of illusionism, including perspective, proportion, volume, shading, values, color, anatomy, memory training, stance, and balance. No detail of craftsmanship is too insignificant; pupils learn how to select and handle pencils, brushes, chalk, charcoal, oil, and even etching.

Who Made This?

It’s helpful to step back for a moment and consider who might want to acquire such skills. The academies’ students are primarily, though by no means exclusively, 18- to 30-year-olds. Raised with the internet, cable television, and such visual spectacles as the Harry Potter films, they have long admired, and made sense of, images enhanced by Photoshop or otherwise computer-generated. They are sophisticated consumers of fast-moving imagery who could easily have followed their contemporaries into digital start-ups, 3-D printing labs, or university art departments that offer do-what-you-feel classes. Yet for various reasons they prefer to master the challenge of drawing and painting by hand.

Most of these students seek to make works of optical fidelity and technical virtuosity animated by their unique creative imaginations. At the heart of this enterprise is close observation of the world, encompassing portraits, figures, animals, plants, inanimate objects, landscapes, cityscapes, interiors, and imaginings of other worlds, both historical and invented. These students are remarkably knowledgeable about their forerunners, be they classical, Renaissance, Baroque, or 19th-century. That’s because they are undertaking what architects call adaptive re-use: the most interesting of their pictures are not antiquarian, yet clearly informed by past achievements.

The single most important stimulus of the boom in atelier enrollment worldwide is the Internet, which has revolutionized the dissemination of imagery and commentary. Art-minded people in their teens and 20s have grown up surfing the web, zooming in on high-resolution images that museums have digitized from their permanent collections, and bookmarking the websites of favorite artists and galleries. Resources such as the Art Renewal Center, Google Images, Flickr, YouTube, and Wikipedia are updated continually, while thousands of blogs, chatrooms, listservs, and Facebook pages allow enthusiasts around the world to exchange ideas informally and ask how specific works were made. Newly created ones are promptly uploaded and commented upon, and links to unfamiliar images and commentaries are shared speedily. Information about these ideas passes from student to student through word of mouth, and through testimonials on web sites, blogs, and Facebook pages.

This virtual world’s lack of gatekeepers — the scholars, curators, critics, professors, or other voices of authority who previously might have curtailed such exchanges —means that no opinion is out of bounds. For this reason, students entering the ateliers are notably unburdened, sometimes even unaware, of the rejection, neglect, or ridicule experienced by realist artists a generation or two older than them. Aware, at least superficially, of a wide range of artistic forms and styles, they do not necessarily consider realism the only path to follow either. This open-mindedness is crucial on two counts. First, these students are neither anti-modern nor philistine, but see modernist aesthetic strategies as one more viable element in their toolkit. Second, the ateliers lack the simmering resentment, sometimes even self-righteousness, that was often conveyed by classically trained realists in previous decades.

What keeps the students focused is a respect for craftsmanship — ostensibly out of sync with our digitized, mass-produced zeitgeist — and also an awareness that once they have learned the rules, they will be free to break them as needed. In many ateliers today, Picasso is often cited as the exemplar of this precious advantage: in adolescence he could draw any sheet in the once-standard curriculum developed by Charles Bargue (published 1868-1871), and by 25 he was rewriting the rulebook for all art history.

What to Depict?

Observation of the “real” world is where realists start: there is the subject depicted, and, if the artist chooses, there is the greater meaning inferred by that subject. The latter may be general (e.g., “a vase of fresh flowers is a thing of beauty to be relished”) or specific (“these blooms hail from a region threatened by unchecked jungle deforestation”). Some observers worry about the perceived tendency of academy students to celebrate only the beautiful — the prettiest woman, the most colorful flowers, the most pristine landscape. The conundrum of beauty in our times has been much debated and does not require repetition here, but suffice it to say that Ani artists are also open to the non-beautiful, be it ugly, horrific, or banal. We know already from Goya, to name just one revered forerunner, that worrisome things can be profound and authentic, while Chardin, Courbet, and Hopper demonstrated that ordinary people, objects, and settings are potentially of equal significance.

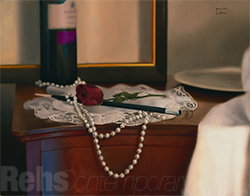

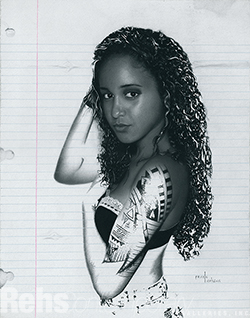

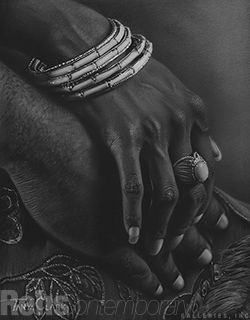

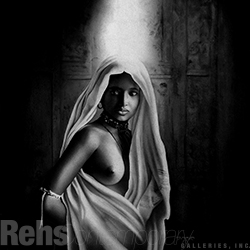

This year’s exhibition, SEX??, contains works reflecting the artists’ ruminations on sexual identity, which, of course, interconnects with almost everything else in life. Though they are impossible to categorize, these newly made images are notably witty, inviting us to puzzle out what’s going on here. Utilizing diverse genres (from trompe l’oeil still life to portraiture, from parodies of Old Masterly compositions to advertising-inspired icons), the artists apparently feel that the boundaries of sexual identity are either gone or increasingly irrelevant. Ambiguity reigns, and sometimes we’re not sure if we should feel aroused or alarmed by what we see. This fluidity is very much in step with the “cutting-edge” imagery we find today in the pricier galleries of Chelsea, except that the Ani works are generally better drawn and painted.

What’s Next?

The blossoming of academies like Ani is a model that works for the art world today. This is change from the ground up, a reminder of artistic self-sufficiency and a declaration that if the university establishment can’t do it, then someone else can. Robust as it may be, however, the revival of the academic tradition is still a niche phenomenon, but its impact on the look of contemporary art promises to grow if artists emerging from the ateliers can find buyers for their works. That’s one reason it’s heartening to see them hanging in a Midtown gallery. Buying from this show will not only enhance your collection, but also register a meaningful vote of confidence in what Ani and its peer academies represent for the future of art.

Peter Trippi has been the editor-in-chief of Fine Art Connoisseur magazine since 2006. He was previously the director of New York City’s Dahesh Museum of Art, which is devoted to 19th-century European academic art.

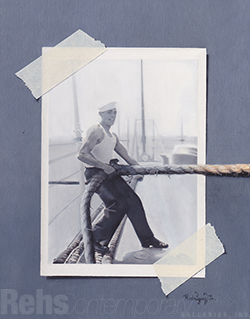

Omar Rodriguez Jr. (Born 1982) For What I've Bound Together (Pair) 10 x 8 inches Signed SOLD Request More Info |

Omar Rodriguez Jr. (Born 1982) For What I've Bound Together (Pair) 10 x 8 inches Signed SOLD Request More Info |

Stuart Dunkel (Born 1952) Spudley, The Shaver (Cleaning up nicely) 12 x 9 inches Signed EXHIBITED Request More Info |

|

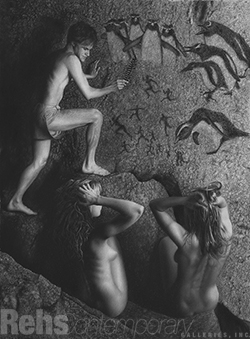

Tim Reynolds (Born 1966) Portrait of the Artist as an Early Man 17 x 13 inches Signed EXHIBITED Request More Info |

|||