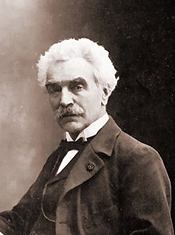

BIOGRAPHY - Jean Leon Gerome (1824 - 1904)

The art of Jean Leon Gérôme combines two of the most popular trends of nineteenth century work—neoclassicism and Orientalism. In Gérôme’s oeuvre, these two modes of expression are often intertwined stylistically with a photographic realism based on meticulous attention to detail. Gérôme was born on 11 May 1824 in Vésoul in the eastern region of France known as the Franche-Comté. Like Gustave Courbet, who was five years older, Gérôme enjoyed the rural life of the Franche-Comté as a child. His family circumstances were comfortable, albeit modest. At age 16, Gérôme persuaded his father to let him try his hand at becoming a painter. The elder Gérôme, who worked as a goldsmith, was not enthusiastic about his son’s career choice, but agreed to let him study with the Paul Delaroche in Paris on a trial basis. Needless to say, Gérôme’s move to Paris, and his study in Delaroche’s atelier, was the beginning of a lifelong passion.

In 1843 when Delaroche closed his studio and moved to Italy, the young Gérôme followed him, always seeking out new classical knowledge and imagery. In particular, he was enchanted with the ruins of Pompeii, and eventually began to incorporate many design elements of the ancient Roman fresco styles into his own painting. Unfortunately, he fell ill in 1844 and was forced to return to Paris to recuperate.

Upon returning to health, Gérôme joined the studio of Charles Gleyre who had taken on many of Delaroche’s former pupils. For Gérôme, this was largely a strategy to enable him to submit paintings for the Prix de Rome competition, which would then allow him to return to Rome and his work there. His career took a somewhat unexpected turn when his entry was rejected because of “inadequate ability in figure drawing”. Hoping to correct this failing, Gérôme painted what he considered an academic exercise featuring a nude youth and a lightly clothed young woman. He added an Italianate landscape and a pair of fighting cocks to the scene almost as an after-thought. Delaroche encouraged him to submit the painting to 1847 Salon, and to his undoubtedly delighted surprise, Cock Fight won a Third Class medal. More importantly, it received very positive critical attention from Théophile Gautier in La Presse, who saw in Gérôme’s work a fresh understanding of themes from antiquity. Gautier went so far as to designate Gérôme and his cohorts as “les néo-grecques” [the neo-Greeks] or “les Pompéistes [the Pompeian painters]—the inheritors of an enduring and elegant classical tradition.

With such popular success, Gérôme no longer felt the need to compete for the Prix de Rome, and turned his attention instead to building his reputation in Paris. The following year, his expectations were met when the state purchased Anacreon, Bacchus and Amor, his submission to the 1848 Salon. Continued sales in the private market, combined with regular government commissions, assured Gérôme’s financial security and established him as one of the leading young academic painters at mid-century.

In 1853, however, Gérôme traveled to Istanbul with the actor Edmond Got, in preparation for a large state project, The Age of Augustus. There, he discovered the alluring world of the Middle East. From this date forward, his subject matter was divided between the classical themes that he favored earlier in his career and an exoticism similar to that of J.-A.-D. Ingres, but with a distinctly photographic realism.

Gérôme’s first trip to Egypt three years later provided even more material for his expanding repertoire of Middle Eastern—and now North African—subjects. Characteristically, his entries for the 1857 Salon reflected the dual aspects of his painting at this stage of his career; The Plain of Thebes, Upper Egypt and Duel After the Masked Ball. Both retain his stylistic preference for precise academic realism, but the subjects could not be more different.

The late 1850s and early 1860s were a period when Gérôme’s classical themes brought him considerable public success. In 1858, he was particularly honored to design Pompeian style interiors for Prince Napoléon-Jerôme Bonaparte’s Paris house; and in 1859, he exhibited two classical subjects at the Salon--King Candaules,and Ave Caesar. Then, in 1861, he received a commission to paint The Reception of the Siamese Ambassadors for the Palace at Versailles. Shortly before he completed this vast project in 1864, Gérôme was also appointed a professor of painting at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, a position he would hold for thirty-nine years. His election to the Institute de France followed immediately thereafter.

Gérôme’s personal life was also enhanced in 1863 by his marriage to Marie Goupil, daughter of the dealer and print editor who supplied so many middle-class art lovers with affordable works in the second half of the nineteenth century. Marriage meant that Gérôme moved out of his group studio at the Boîte à Thé on the rue Notre Dame des Champs, and into a more settled existence with his wife. He continued to paint both classical and orientalist themes, and increasingly devoted his time to teaching the next generation in his classes at the Ecole.

One of the most remarkable shifts in Gérôme’s career was his emergence as a sculptor in the late 1870s. Surprising nearly everyone, he exhibited a large bronze sculpture of a gladiator trampling his victim at the 1878 Salon. This figure was essentially a three-dimensional representation of the triumphant gladiator in his 1872 Roman spectacle painting, Pollice verso. At the same time, he began experimenting with marble sculpting, eventually going so far as to tint the marble with colors in imitation of the technique reportedly practiced by ancient Greeks and Romans.

No account of Gérôme’s life would be straightforward without mentioning his public opposition to the work of many contemporaries, including Manet, Rodin, Puvis de Chavannes, and the Impressionists. As an influential—and highly popular—professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Gérôme was in a unique position to influence future generations of painters. Perhaps it was his sense of responsibility to the French academic tradition that predisposed him to find the avant-garde ideas of the modernists so antithetical.

Gérôme continued to teach until 1902, and to work actively until his death. The New York Times obituary for him notes: “Yesterday several friends lunched with M. Gérôme at his house, and after luncheon he took them to his studio to show them a statue representing Corinth, of which he was the sculptor. The statue had just been finished, and he was about to color it.” [i] He died on 10 January 1904 in Paris, just a few months shy of his 80th birthday.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Art Institute, Dayton, Ohio

Art Institute of Chicago

Kunsthalle, Hamburg

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Louvre, Paris

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Musée Augustins, Toulouse

Musee Condé, Chantily

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes

Musée Municipale, Brest

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford, Connecticut

[i] “Jean Leon Gerome Dead” New York Times, January 11, 1904.